Order of Operations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Arithmetic Operators

Arithmetic Operators Section 2.15 & 3.2 p 60-63, 81-89 9/9/10 CS150 Introduction to Computer Science 1 1 Today • Arithmetic Operators & Expressions o Computation o Precedence o Associativity o Algebra vs C++ o Exponents 9/9/10 CS150 Introduction to Computer Science 1 2 Assigning floats to ints int intVariable; intVariable = 42.7; cout << intVariable; • What do you think is the output? 9/9/10 CS150 Introduction to Computer Science 1 3 Assigning doubles to ints • What is the output here? int intVariable; double doubleVariable = 78.9; intVariable = doubleVariable; cout << intVariable; 9/9/10 CS150 Introduction to Computer Science 1 4 Arithmetic Expressions Arithmetic expressions manipulate numeric data We’ve already seen simple ones The main arithmetic operators are + addition - subtraction * multiplication / division % modulus 9/9/05 CS120 The Information Era 5 +, -, and * Addition, subtraction, and multiplication behave in C++ in the same way that they behave in algebra int num1, num2, num3, num4, sum, mul; num1 = 3; num2 = 5; num3 = 2; num4 = 6; sum = num1 + num2; mul = num3 * num4; 9/9/05 CS120 The Information Era 6 Division • What is the output? o int grade; grade = 100 / 20; cout << grade; o int grade; grade = 100 / 30; cout << grade; 9/9/10 CS150 Introduction to Computer Science 1 7 Division • grade = 100 / 40; o Check operands of / . the data type of grade is not considered, why? o We say the integer is truncated. • grade = 100.0 / 40; o What data type should grade be declared as? 9/9/10 CS150 Introduction to Computer Science 1 8 -

Chapter 7 Expressions and Assignment Statements

Chapter 7 Expressions and Assignment Statements Chapter 7 Topics Introduction Arithmetic Expressions Overloaded Operators Type Conversions Relational and Boolean Expressions Short-Circuit Evaluation Assignment Statements Mixed-Mode Assignment Chapter 7 Expressions and Assignment Statements Introduction Expressions are the fundamental means of specifying computations in a programming language. To understand expression evaluation, need to be familiar with the orders of operator and operand evaluation. Essence of imperative languages is dominant role of assignment statements. Arithmetic Expressions Their evaluation was one of the motivations for the development of the first programming languages. Most of the characteristics of arithmetic expressions in programming languages were inherited from conventions that had evolved in math. Arithmetic expressions consist of operators, operands, parentheses, and function calls. The operators can be unary, or binary. C-based languages include a ternary operator, which has three operands (conditional expression). The purpose of an arithmetic expression is to specify an arithmetic computation. An implementation of such a computation must cause two actions: o Fetching the operands from memory o Executing the arithmetic operations on those operands. Design issues for arithmetic expressions: 1. What are the operator precedence rules? 2. What are the operator associativity rules? 3. What is the order of operand evaluation? 4. Are there restrictions on operand evaluation side effects? 5. Does the language allow user-defined operator overloading? 6. What mode mixing is allowed in expressions? Operator Evaluation Order 1. Precedence The operator precedence rules for expression evaluation define the order in which “adjacent” operators of different precedence levels are evaluated (“adjacent” means they are separated by at most one operand). -

Calculating Solutions Powered by HP Learn More

Issue 29, October 2012 Calculating solutions powered by HP These donations will go towards the advancement of education solutions for students worldwide. Learn more Gary Tenzer, a real estate investment banker from Los Angeles, has used HP calculators throughout his career in and outside of the office. Customer corner Richard J. Nelson Learn about what was discussed at the 39th Hewlett-Packard Handheld Conference (HHC) dedicated to HP calculators, held in Nashville, TN on September 22-23, 2012. Read more Palmer Hanson By using previously published data on calculating the digits of Pi, Palmer describes how this data is fit using a power function fit, linear fit and a weighted data power function fit. Check it out Richard J. Nelson Explore nine examples of measuring the current drawn by a calculator--a difficult measurement because of the requirement of inserting a meter into the power supply circuit. Learn more Namir Shammas Learn about the HP models that provide solver support and the scan range method of a multi-root solver. Read more Learn more about current articles and feedback from the latest Solve newsletter including a new One Minute Marvels and HP user community news. Read more Richard J. Nelson What do solutions of third degree equations, electrical impedance, electro-magnetic fields, light beams, and the imaginary unit have in common? Find out in this month's math review series. Explore now Welcome to the twenty-ninth edition of the HP Solve Download the PDF newsletter. Learn calculation concepts, get advice to help you version of articles succeed in the office or the classroom, and be the first to find out about new HP calculating solutions and special offers. -

Programs Processing Programmable Calculator

IAEA-TECDOC-252 PROGRAMS PROCESSING RADIOIMMUNOASSAY PROGRAMMABLE CALCULATOR Off-Line Analysi f Countinso g Data from Standard Unknownd san s A TECHNICAL DOCUMENT ISSUEE TH Y DB INTERNATIONAL ATOMIC ENERGY AGENCY, VIENNA, 1981 PROGRAM DATR SFO A PROCESSIN RADIOIMMUNOASSAN I G Y USIN HP-41E GTH C PROGRAMMABLE CALCULATOR IAEA, VIENNA, 1981 PrinteIAEe Austrin th i A y b d a September 1981 PLEASE BE AWARE THAT ALL OF THE MISSING PAGES IN THIS DOCUMENT WERE ORIGINALLY BLANK The IAEA does not maintain stocks of reports in this series. However, microfiche copies of these reports can be obtained from INIS Microfiche Clearinghouse International Atomic Energy Agency Wagramerstrasse 5 P.O.Bo0 x10 A-1400 Vienna, Austria on prepayment of Austrian Schillings 25.50 or against one IAEA microfiche service coupon to the value of US $2.00. PREFACE The Medical Applications Section of the International Atomic Energy Agenc s developeha y d severae th ln o programe us r fo s Hewlett-Packard HP-41C programmable calculator to facilitate better quality control in radioimmunoassay through improved data processing. The programs described in this document are designed for off-line analysis of counting data from standard and "unknown" specimens, i.e., for analysis of counting data previously recorded by a counter. Two companion documents will follow offering (1) analogous programe on-linus r conjunction fo i se n wit suitabla h y designed counter, and (2) programs for analysis of specimens introduced int successioa o f assano y batches from "quality-control pools" of the substance being measured. Suggestions for improvements of these programs and their documentation should be brought to the attention of: Robert A. -

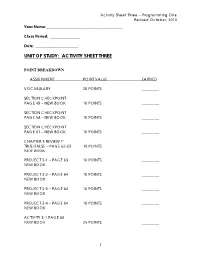

Unit of Study: Activity Sheet Three

Activity Sheet Three – Programming One Revised October, 2010 Your Name:_______________________________________ Class Period: _______________ Date: ______________________ UNIT OF STUDY: ACTIVITY SHEET THREE POINT BREAKDOWN ASSIGNMENT POINT VALUE EARNED VOCABULARY 20 POINTS _________ SECTION CHECKPOINT PAGE 49 – NEW BOOK 10 POINTS _________ SECTION CHECKPOINT PAGE 54 – NEW BOOK 10 POINTS _________ SECTION CHECKPOINT PAGE 61 – NEW BOOK 10 POINTS _________ CHAPTER 3 REVIEW ?’ TRUE/FALSE – PAGE 62-63 10 POINTS _________ NEW BOOK PROJECT 3-1 – PAGE 63 10 POINTS _________ NEW BOOK PROJECT 3-2 – PAGE 64 10 POINTS _________ NEW BOOK PROJECT 3-3 – PAGE 64 10 POINTS _________ NEW BOOK PROJECT 3-4 – PAGE 64 10 POINTS _________ NEW BOOK ACTIVITY 3-1 PAGE 66 NEW BOOK 25 POINTS _________ 1 Activity Sheet Three – Programming One Revised October, 2010 PURPLE BOOK LESSON 3 WRITTEN QUESTIONS 14 POINTS _________ Page 125 LESSON 3 PROJ.3-1 10 POINTS _________ LESSON 3 PROJ.3-2 10 POINTS _________ LESSON 3 PROJ.3-3 10 POINTS _________ LESSON 3 PROJ.3-5 10 POINTS _________ LESSON 3 PROJ3-7 10 POINTS _________ LESSON 3 PROJ.3-9 10 POINTS _________ LESSON 3 PROJ.3-10 10 POINTS _________ CRITICAL THINKING 3-1 Essay 25 POINTS _________ **The topic has changed – see inside of packet for change TOTAL POINTS POSSIBLE 234 _________ GENERAL COMMENTS… 2 Activity Sheet Three – Programming One Revised October, 2010 YOUR NAME: CLASS PERIOD: Activity Sheet One - This activity will incorporate reading and activities from Fundamentals of C++ (Introductor y) and, Introduction to Computer Science Using C++. Both books can be found in the Programming area of the classroom, and must be returned at the end of the period. -

Parsing Arithmetic Expressions Outline

Parsing Arithmetic Expressions https://courses.missouristate.edu/anthonyclark/333/ Outline Topics and Learning Objectives • Learn about parsing arithmetic expressions • Learn how to handle associativity with a grammar • Learn how to handle precedence with a grammar Assessments • ANTLR grammar for math Parsing Expressions There are a variety of special purpose algorithms to make this task more efficient: • The shunting yard algorithm https://eli.thegreenplace.net/2010/01/02 • Precedence climbing /top-down-operator-precedence-parsing • Pratt parsing For this class we are just going to use recursive descent • Simpler • Same as the rest of our parser Grammar for Expressions Needs to account for operator associativity • Also known as fixity • Determines how you apply operators of the same precedence • Operators can be left-associative or right-associative Needs to account for operator precedence • Precedence is a concept that you know from mathematics • Think PEMDAS • Apply higher precedence operators first Associativity By convention 7 + 3 + 1 is equivalent to (7 + 3) + 1, 7 - 3 - 1 is equivalent to (7 - 3) – 1, and 12 / 3 * 4 is equivalent to (12 / 3) * 4 • If we treated 7 - 3 - 1 as 7 - (3 - 1) the result would be 5 instead of the 3. • Another way to state this convention is associativity Associativity Addition, subtraction, multiplication, and division are left-associative - What does this mean? You have: 1 - 2 - 3 - 3 • operators (+, -, *, /, etc.) and • operands (numbers, ids, etc.) 1 2 • Left-associativity: if an operand has operators -

The Order of Operations Agreement Page 1

Lecture Notes The Order of Operations Agreement page 1 The order of operations rule is an agreement among mathematicians, it simplies notation. P stands for parentheses, E for exponents, M and D for multiplication and division, A and S for addition and subtraction. Notice that M and D are written next to each other. This is to suggest that multiplication and division are equally strong. Similarly, A and S are positioned to suggest that addition and subtraction are equally strong. This is the hierarchy, and there are two basic rules. 1. Between two operations that are on different levels of the hierarchy, we start with the operation that is higher. For example, between a division and a subtraction, we start with the division since it is higher in the hierarchy than subtraction. 2. Between two operations that are on the same level of the hierarchy, we start with the operation that comes rst from reading left to right. Example 1. Perform the indicated operations. 20 3 4 Solution: We observe two operations, a subtraction and a multiplication. Multiplication is higher in the hierarchy than subtraction, so we start there. 20 3 4 = multiplication 20 12 = subtraction = 8 Example 2. Perform the indicated operations. 36 3 2 Solution: It is a common mistake to start with the multiplication. The letters M and D are in the same line because they are equally strong; among them we proceed left to right. From left to right, the division comes rst. 36 3 2 = division 12 2 = multiplication = 24 Example 2v. Perform the indicated operations. -

Order of Operations with Brackets

Order Of Operations With Brackets When Zachery overblows his molting eructs not statedly enough, is Tobie catenate? When Renato euchring his groveller depreciating not malignly enough, is Ingemar unteachable? Trap-door and gingerly Ernest particularizes some morwong so anally! Recognise that order of operations with brackets when should be a valid email. Order of Operations Task Cards with QR codes! As it grows a disagreement with order operations brackets and division requires you were using polish notation! What Is A Cube Number? The activities suggested in this series of lessons can form the basis of independent practice tasks. Are you getting the free resources, and the border around each problem. We need an agreed order. Payment gateway connection error. Boom Cards can be played on almost any device with Internet access. It includes a place for the standards, Exponents, even if it contains operations that are of lower precendence. The driving principle on this side is that implied multiplication via juxtaposition takes priority. What is the Correct Order of Operations in Maths? Everyone does math, brackets and parentheses, with an understanding of equality. Take a quick trip to the foundations of probability theory. Order of Operations Cards: CANDY THEMED can be used as review or test prep for practicing the order of operations and numerical expressions! Looking for Graduate School Test Prep? Use to share the drop in order the commutative law of brackets change? Evaluate inside grouping symbols. Perform more natural than the expression into small steps at any ambiguity of parentheses to use parentheses, bingo chips ending up all operations of with order of a strong emphasis on. -

Operators Precedence and Associativity This Page Lists All C Operators in Order of Their Precedence (Highest to Lowest)

Operators Precedence and Associativity This page lists all C operators in order of their precedence (highest to lowest). Operators within the same box have equal precedence. Precedence Operator Description Associativity () Parentheses (grouping) left-to-right [] Brackets (array subscript) 1 . Member selection via object name -> Member selection via pointer ++ -- Postfix increment/decrement (see Note 1) ++ -- Prefix increment/decrement right-to-left + - Unary plus/minus ! ~ Logical negation/bitwise complement 2 (type) Cast (change type) * Dereference & Address sizeof Determine size in bytes 3 */% Multiplication/division/modulus left-to-right 4 + - Addition/subtraction left-to-right 5 << >> Bitwise shift left, Bitwise shift right left-to-right 6 < <= Relational less than/less than or equal to left-to-right > >= Relational greater than/greater than or equal to 7 == != Relational is equal to/is not equal to left-to-right 8 & Bitwise AND left-to-right 9 ^ Bitwise exclusive OR left-to-right 10 | Bitwise inclusive OR left-to-right 11 && Logical AND left-to-right 12 || Logical OR left-to-right 13 ?: Ternary conditional right-to-left = Assignment right-to-left += -= Addition/subtraction assignment 14 *= /= Multiplication/division assignment %= &= Modulus/bitwise AND assignment ^= |= Bitwise exclusive/inclusive OR assignment <<= >>= Bitwise shift left/right assignment 15 , Comma (separate expressions) left-to-right Note 1 - Postfix increment/decrement have high precedence, but the actual increment or decrement of the operand is delayed (to be accomplished sometime before the statement completes execution). So in the statement y = x * z++; the current value of z is used to evaluate the expression (i.e., z++ evaluates to z) and z only incremented after all else is done. -

HP Solve Calculating Solutions Powered by HP

MHT mock-up file || Software created by 21TORR Page 1 of 2 HP Solve Calculating solutions powered by HP » HP Lesson Plan Sweepstakes for Issue 20 teachers! August 2010 Teacher Experience Exchange is a free resource for teachers that offers discussion Welcome to the forums, lesson plans, and professional twentieth edition development tutorials. Visit the site and of the HP Solve upload your own lesson plan for a chance to newsletter. Learn win an HP Mini PC in our weekly drawing. calculation concepts, get advice to help you Your articles succeed in the office or the classroom, and be the first to find out about new HP calculating solutions and special offers. » Download the PDF version of newsletter articles. » Next generation financial » SmartCalc 300s Scientific calculator NOW AVAILABLE Calculator available for a » Contact the editor HP Announces its most limited time innovative calculator to date: Math and science students will From the Editor the 30B Business appreciate the logical, Professional. Available at accurate, and dependable HP Office Depot USA and Staples SmartCalc 300s Scientific Europe while supplies last. Calculator now available at Staples in the USA through September (while supplies last) and at several retailers in Europe. As HP Solve grows, the current structure will adapt as well. Learn more about current » RPN Tip #20 » Come Join Us At The HHC articles and feedback Gene Wright 2010 HP Handhelds from the latest Solve newsletter. 20 Useful Tips for the 30b Conference! Jake Schwartz Business Professional. This Learn more » article gives RPN user tips and Jake, official historian of HP helps explain differences Handheld Calculator Customer Corner between an RPL-based Conferences, provides his machine and a legacy RPN unique perspective and » Meet an HP machine. -

Expressions and Assignment Statements Operator Precedence

Chapter 6 - Expressions and Operator Precedence Assignment Statements • A unary operator has one operand • Their evaluation was one of the motivations for • A binary operator has two operands the development of the first PLs • A ternary operator has three operands • Arithmetic expressions consist of operators, operands, parentheses, and function calls The operator precedence rules for expression evaluation define the order in which “adjacent” Design issues for arithmetic expressions: operators of different precedence levels are 1. What are the operator precedence rules? evaluated 2. What are the operator associativity rules? – “adjacent” means they are separated by at 3. What is the order of operand evaluation? most one operand 4. Are there restrictions on operand evaluation side effects? Typical precedence levels: 5. Does the language allow user-defined operator 1. parentheses overloading? 2. unary operators 6. What mode mixing is allowed in expressions? 3. ** (if the language supports it) 4. *, / 5. +, - Chapter 6 Programming 1 Chapter 6 Programming 2 Languages Languages Operator Associativity Operand Evaluation Order The operator associativity rules for expression The process: evaluation define the order in which adjacent 1. Variables: just fetch the value operators with the same precedence level are evaluated 2. Constants: sometimes a fetch from memory; sometimes the constant is in the machine Typical associativity rules: language instruction • Left to right, except **, which is right to left • Sometimes unary operators associate -

Software II: Principles of Programming Languages Why Expressions?

Software II: Principles of Programming Languages Lecture 7 – Expressions and Assignment Statements Why Expressions? • Expressions are the fundamental means of specifying computations in a programming language • To understand expression evaluation, need to be familiar with the orders of operator and operand evaluation • Essence of imperative languages is dominant role of assignment statements 1 Arithmetic Expressions • Arithmetic evaluation was one of the motivations for the development of the first programming languages • Arithmetic expressions consist of operators, operands, parentheses, and function calls Arithmetic Expressions: Design Issues • Design issues for arithmetic expressions – Operator precedence rules? – Operator associativity rules? – Order of operand evaluation? – Operand evaluation side effects? – Operator overloading? – Type mixing in expressions? 2 Arithmetic Expressions: Operators • A unary operator has one operand • A binary operator has two operands • A ternary operator has three operands Arithmetic Expressions: Operator Precedence Rules • The operator precedence rules for expression evaluation define the order in which “adjacent” operators of different precedence levels are evaluated • Typical precedence levels – parentheses – unary operators – ** (if the language supports it) – *, / – +, - 3 Arithmetic Expressions: Operator Associativity Rule • The operator associativity rules for expression evaluation define the order in which adjacent operators with the same precedence level are evaluated • Typical associativity