Challenges and Experiences in Organizing Home-Based Workers in Bulgaria Dave Spooner1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

(Epicometis) Hirta (PODA) (Coleoptera: Cetoniidae) in Bulgaria

ACTA ZOOLOGICA BULGARICA Acta zool. bulg., 63 (3), 2011: 269-276 Employing Floral Baited Traps for Detection and Seasonal Monitoring of Tropinota (Epicometis) hirta (PODA ) (Coleoptera: Cetoniidae) in Bulgaria Mitko A. Subchev1, Teodora B. Toshova1, Radoslav A. Andreev2, Vilina D. Petrova3, Vasilina D. Maneva4, Teodora S. Spasova5, Nikolina T. Marinova5, Petko M. Minkov, Dimitar I. Velchev6 1 Institute of Biodiversity and Ecosystem Research, 2 Gagarin str., 1113 Sofia, Bulgaria 2 Agricultural University, 12Mendeleev str., 4000 Plovdiv, Bulgaria 3 Institute of Agriculture, Sofijsko shoes, 2500 Kyustendil, Bulgaria 4 Institute of Agriculture, 1 Industrialna str., 8400 Karnobat, Bulgaria 5 Institute of Mountainous Animal Breeding and Agriculture, 281 Vasil Levski str, 5600 Troyan, Bulgaria 6 Maize Research Institute, 5835 Knezha, Bulgaria Abstract: The potential of commercially available light blue VARb3k traps and baits for T. hirta (Csalomon®, Plant Protection Institute, Budapest, Hungary) as a new tool for detection and describing the seasonal flight pat- terns of Tropinota (Epicometis) hirta (PODA ) was proved in eight sites in Bulgaria in 2009 and 2010. The traps showed very high efficiency in both cases of high and low population level of the pest. Significant catches of T. hirta were recorded in Dryanovo, Karnobat, Knezha, Kyustendil, Petrich and Plovdiv. As a whole the beetles appeared in the very end of March – beginning of April and reached their peak flight in the second half of April – beginning of May; catches were recorded up to the middle of July. The bait/traps system used in our field work showed very high species selectivity. In nine out of ten cases the catches of T. -

Company Profile

www.ecobulpack.com COMPANY PROFILE KEEP BULGARIA CLEAN FOR THE CHILDREN! PHILIPPE ROMBAUT Chairman of the Board of Directors of ECOBULPACK Executive Director of AGROPOLYCHIM JSC-Devnia e, ECOBULPACK are dedicated to keeping clean the environment of the country we live Wand raise our children in. This is why we rely on good partnerships with the State and Municipal Authorities, as well as the responsible business managers who have supported our efforts from the very beginning of our activity. Because all together we believe in the cause: “Keep Bulgaria clean for the children!” VIDIO VIDEV Executive Director of ECOBULPACK Executive Director of NIVA JSC-Kostinbrod,VIDONA JSC-Yambol t ECOBULPACK we guarantee the balance of interests between the companies releasing A packed goods on the market, on one hand, and the companies collecting and recycling waste, on the other. Thus we manage waste throughout its course - from generation to recycling. The funds ECOBULPACK accumulates are invested in the establishment of sustainable municipal separate waste collection systems following established European models with proven efficiency. DIMITAR ZOROV Executive Director of ECOBULPACK Owner of “PARSHEVITSA” Dairy Products ince the establishment of the company we have relied on the principles of democracy as Swell as on an open and fair strategy. We welcome new shareholders. We offer the business an alternative in fulfilling its obligations to utilize packaged waste, while meeting national legislative requirements. We achieve shared responsibilities and reduce companies’ product- packaging fees. MILEN DIMITROV Procurator of ECOBULPACK s a result of our joint efforts and the professionalism of our work, we managed to turn AECOBULPACK JSC into the largest organization utilizing packaging waste, which so far have gained the confidence of more than 3 500 companies operating in the country. -

Luftwaffe Airfields 1935-45 Bulgaria

Luftwaffe Airfields 1935-45 Luftwaffe Airfields 1935-45 Bulgaria By Henry L. deZeng IV General Map Edition: November 2014 Luftwaffe Airfields 1935-45 Copyright © by Henry L. deZeng IV (Work in Progress). (1st Draft 2014) Blanket permission is granted by the author to researchers to extract information from this publication for their personal use in accordance with the generally accepted definition of fair use laws. Otherwise, the following applies: All rights reserved. No part of this publication, an original work by the authors, may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form, or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of the author. Any person who does any unauthorized act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages. This information is provided on an "as is" basis without condition apart from making an acknowledgement of authorship. Luftwaffe Airfields 1935-45 Airfields Bulgaria Introduction Conventions 1. For the purpose of this reference work, “Bulgaria” generally means the territory belonging to the country on 6 April 1941, the date of the German invasion and occupation of Yugoslavia and Greece. The territory occupied and acquired by Bulgaria after that date is not included. 2. All spellings are as they appear in wartime German documents with the addition of alternate spellings where known. Place names in the Cyrillic alphabet as used in the Bulgarian language have been transliterated into the English equivalent as they appear on Google Earth. 3. It is strongly recommended that researchers use the search function because each airfield and place name has alternate spellings, sometimes 3 or 4. -

Annex REPORT for 2019 UNDER the “HEALTH CARE” PRIORITY of the NATIONAL ROMA INTEGRATION STRATEGY of the REPUBLIC of BULGAR

Annex REPORT FOR 2019 UNDER THE “HEALTH CARE” PRIORITY of the NATIONAL ROMA INTEGRATION STRATEGY OF THE REPUBLIC OF BULGARIA 2012 - 2020 Operational objective: A national monitoring progress report has been prepared for implementation of Measure 1.1.2. “Performing obstetric and gynaecological examinations with mobile offices in settlements with compact Roma population”. During the period 01.07—20.11.2019, a total of 2,261 prophylactic medical examinations were carried out with the four mobile gynaecological offices to uninsured persons of Roma origin and to persons with difficult access to medical facilities, as 951 women were diagnosed with diseases. The implementation of the activity for each Regional Health Inspectorate is in accordance with an order of the Minister of Health to carry out not less than 500 examinations with each mobile gynaecological office. Financial resources of BGN 12,500 were allocated for each mobile unit, totalling BGN 50,000 for the four units. During the reporting period, the mobile gynecological offices were divided into four areas: Varna (the city of Varna, the village of Kamenar, the town of Ignatievo, the village of Staro Oryahovo, the village of Sindel, the village of Dubravino, the town of Provadia, the town of Devnya, the town of Suvorovo, the village of Chernevo, the town of Valchi Dol); Silistra (Tutrakan Municipality– the town of Tutrakan, the village of Tsar Samuel, the village of Nova Cherna, the village of Staro Selo, the village of Belitsa, the village of Preslavtsi, the village of Tarnovtsi, -

Between Development and Preservation: Planning for Changing Urban and Rural Cultural Landscapes at Municipal Level

MANAGEMENT OF HISTORICALLY DEVELOPED URBAN AND RURAL LANDSCAPES IN CENTRAL, EASTERN AND SOUTH EASTERN EUROPE 12th – 14th September 2016, Lednice (Czech Republic) BETWEEN DEVELOPMENT AND PRESERVATION: PLANNING FOR CHANGING URBAN AND RURAL CULTURAL LANDSCAPES AT MUNICIPAL LEVEL Milena Tasheva – Petrova University of Architecture, Civil Engineering and Geodesy , Faculty of Architecture, Urban Planning Department Introduction. The Context • 256 Comprehensive Development plans of municipalities (CDPM) to be created by the year 2018 • Landscape –to design and assign territories for implementation of preventive and restorative (The Territorial Management Act) • Landscape – Part of the Strategic Environmental Assessment of the CDPM THE SAMPLE OF THE STUDY: 9 MUNICIPALITIES MUNICIPA LOCATION POPULATION NUMBER AREA Area NUMBER OF SETTLEMENTS LITY (1946, 1985, 2011) [HA] Footprint DZHEBEL SC Region 16 122, 22 851 22 980 47 settlements: Kardzhali Province 8 163 1 town; 46 villages KAVARNA NE Region 16 320 48 136 21 settlements: Dobrich province 1 town; 20 villages KIRKOVO SC Region 22 280 53 787 3 settlements: Kardzhali Province 73 village; 2 v. without population Trans-border R (EL) KOPRIV- SW region 2 475, 3 255 13 887 1 town SHTITCA Sofia Province 2 410 MALKO SE region 10 857, 7 036 79 800 13 settlements: TARNOVO Bourgas Province 3 840 1 town, 12 villages Trans-border R (TR) NIKOPOL NW Region 26 301, 17 785 41 827 14 settlements: Pleven Province 9 305 1 town, 13 villages Trans-border R (RO) OPAN SE Region 2 950 25 747 13 settlements: Stara Zagora Province 13 villages PERNIK SW region, Pernik 59 593, 117 615 48 420 24 settlements: Province 97 181 2 towns and 22 villages TROYAN NW Region 39 701, 45 338 60 243 38 settlements transformed into 22 in Lovetch Province 32 339 2012 MUNICI- PREVAILING NATURAL NATURAL RISK AND HAZARD PROTECTED AREAS PROTECTED AREAS PALITY LANDSCAPES; AV. -

What Are the Barriers to the Roma Integration According to Representatives of the Local Authorities

WHAT ARE THE BARRIERS TO THE ROMA INTEGRATION ACCORDING TO REPRESENTATIVES OF THE LOCAL AUTHORITIES ANALYSIS OF THE RESULTS OF A QUALITY RESEARCH CONDUCTED IN EIGHT MUNICIPALITIES ILONA TOMOVA Integro Association, Razgrad 2011 1 The research was conducted within the campaign “Thank You, Mayor!”, which is part of the international pilot program: “Pan-European Coordination of Roma Integration Methods”, implemented by several partnering organizations: European Network of the Roma Organizations (ERGO), “Spolu International Foundation” Netherlands, “Policy centre for Roma and minorities”- Romania, “Roma Active- Albania”- Albania and Integro Association- Bulgaria. The campaign in Bulgaria was realized by 15 partnering organizations: Integro Association-Razgrad, “Diverse and Equal”-Sofia, “World Without Borders”-Stara Zagora „Health of Roma”- Sliven, LARGO- Kyustendil, „Center for Strategies on Minority Issues”- Varna, „For a New World”- Vratsa, „Iskra” - Shumen, „Roma Solidarity”- Petrich, Mother’s Center „Good mothers- good children”- Sandanski, „Detelina”- Byala (Ruse region), „Sun for all”- Peshtera, „New Horizons”- Panagyurishte, „Indi-Roma”- Kuklen, „New Path”- Hayredin. The entire responsibility for the content of the document rests with the "Integro” Association and under no circumstances can be assumed that the described views and opinions reflect the official point of the European Union. The project is funded by the Directorate General "Regional Policy", European Commission 2 INTRODUCTION Despite of the National political framework -

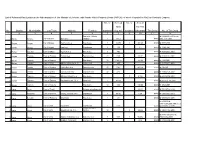

List of Released Real Estates in the Administration of the Ministry Of

List of Released Real Estates in the Administration of the Ministry of Defence, with Private Public Property Deeds (PPPDs), of which Property the MoD is Allowed to Dispose No. of Built-up No. of Area of Area the Plot No. District Municipality City/Town Address Function Buildings (sq. m.) Facilities (decares) Title Deed No. of Title Deed 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Part of the Military № 874/02.05.1997 for the 1 Burgas Burgas City of Burgas Slaveykov Hospital 1 545,4 PPPD whole real estate 2 Burgas Burgas City of Burgas Kapcheto Area Storehouse 6 623,73 3 29,143 PPPD № 3577/2005 3 Burgas Burgas City of Burgas Sarafovo Storehouse 6 439 5,4 PPPD № 2796/2002 4 Burgas Nesebar Town of Obzor Top-Ach Area Storehouse 5 496 PPPD № 4684/26.02.2009 5 Burgas Pomorie Town of Pomorie Honyat Area Barracks area 24 9397 49,97 PPPD № 4636/12.12.2008 6 Burgas Pomorie Town of Pomorie Storehouse 18 1146,75 74,162 PPPD № 1892/2001 7 Burgas Sozopol Town of Atiya Military station, by Bl. 11 Military club 1 240 PPPD № 3778/22.11.2005 8 Burgas Sredets Town of Sredets Velikin Bair Area Barracks area 17 7912 40,124 PPPD № 3761/05 9 Burgas Sredets Town of Debelt Domuz Dere Area Barracks area 32 5785 PPPD № 4490/24.04.2008 10 Burgas Tsarevo Town of Ahtopol Mitrinkovi Kashli Area Storehouse 1 0,184 PPPD № 4469/09.04.2008 11 Burgas Tsarevo Town of Tsarevo Han Asparuh Str., Bl. -

First Investment Bank AD Points for Servicing Customers of the 'Corporate Commercial Bank'

First Investment Bank AD Points for servicing customers of the 'Corporate Commercial Bank' Points for Type of Customers Name of Business hours (Monday servicing Address servicecash/ Individual/ branch/office through Friday) customers non-cash Corporate Asenovgrad Asenovgrad Asenovgrad 4230, 3, Nickolay Haytov Sq. 9:00 - 17:30 cash/ non- cash ind./ corp. Balchik Balchik Balchik 9600, 25, Primorska St. 9:00 - 17:30 cash/ non- cash ind./ corp. Bansko Bansko Bansko 2770, 68, Tzar Simeon St. 9:00 - 17:30 cash/ non- cash ind./ corp. Bansko Bansko Municipality Bansko 2770, 12, Demokratziya Sq. 9:00 - 12:00 + 13:00 - 17:30 cash/ non- cash ind./ corp. Bansko Strazhite Bansko 2770, 7, Glazne St. 9:00 - 22:00 (15.12-30.03), cash/ non- cash ind./ corp. 9:00 – 17:30 (01.12-14.12 и 31.03-15.04), 9:00 - 13:00 + 14:00 - 17:30 (16.04-30.11) Belene Belene Belene 5930, 2, Ivan Vazov St. 9:00 - 17:30 cash/ non- cash ind./ corp. Blagoevgrad Blagoevgrad Blagoevgrad 2700, 11, Kiril i Metodiy Blvd. 9:00 - 17:30 cash/ non- cash ind./ corp. Blagoevgrad GUM Blagoevgrad 2700, 6, Trakia St. 9:00 - 17:30 cash/ non- cash ind./ corp. Borovets Rila Hotel Borovets 2010, Rila Hotel 9:00 –19:00 cash/ non- cash ind./ corp. Botevgrad Botevgrad Botevgrad 2140, 5, Osvobozhdenie Sq. 9:00 - 17:30 cash/ non- cash ind./ corp. Burgas Bratya Miladinovi Burgas 8000, Zh. k. (Quarter) Bratya 9:00 - 17:30 cash/ non- cash ind./ corp. Miladinovi, bl. 117, entr. 5 Burgas Burgas Burgas 8000, 58, Alexandrovska St. -

Organisation of Work, Time, Efficiency, Competition Dobri Zhelyazkov And

Organisation of work, time, efficiency, competition Dobri Zhelyazkov and the first textile factory in Bulgaria and on the Balkan peninsula (by Aleksander Zoev) Dobri Zhelyazkov Fotisov - Factory maker (1800 - 1865) is a Bulgarian entrepreneur who founded the first textile production in Sliven and the Balkans in the 1830s. (Monument to Dobri Zhelyazkov in Borisova gradina, Sofia.) Born in Sliven,Ottoman Empire(nowadays Bulgaria), Zhelyazkov studied at the Greek school in his native town. Upon finishing, he tried several handcrafts until he discovered his talent in homespun tailoring. In the 1820s Zhelyazkov introduced an improved wool-carding machine in his work, drawing down upon himself the anger of his competitors, who complained to the authorities. However, this did not stop Zhelyazkov. In 1826, Zhelyazkov co-founded the Secret Brotherhood (Тайно братство, Tayno bratstvo) together with Dr Ivan Seliminski. The organization, initially a social one, would develop into a political society. Following the outbreak of the Russo-Turkish War of 1828–1829, Zhelyazkov took part in the organization of an uprising in the region of Sliven. However, after the signing of the Treaty of Adrianople in 1829, Zhelyazkov was forced to flee to Russia in 1830. He settled in Crimea, marrying another emigrant, Mariyka Yanakieva, and became a wool and cloth merchant, touring the country and observing textile production. In 1834, Zhelyazkov returned to Sliven with his family and settled in his wife's house. There he constructed a production building (2.20 × 4.80 m, 3.80 m high), where he fitted looms, carding and spinning machines constructed by local smiths to designs brought from Russia. -

Fast Delivery

Delivery and Returns Delivery rates: We strive to offer an unbeatable service and deliver our products safely and cost-effectively. Our main focus is serving our The delivery is performed by a third-party delivery service provider. customers’ needs with a combination of great design, quality products, value for money, respect for the environment and All orders under 20 kg are shipped by courier with door-to-door delivery service. outstanding service. Please read our Delivery terms and details before you complete your order. If you have any questions, we advise that you contact us at 080019889 and speak with one of our customer service associates. All orders over 20 kg are shipped by transport company with delivery to building address service. All orders are processed within 72 hours from the day following the day on which the order is confirmed and given to the courier or transport company for delivery. After the ordered goods are given to courier or transport company for delivery, we will send you a tracking number, which will allow you to check on their website for recent status. The delivery price is not included in the price of the goods. The transport and delivery cots depend on the weight and volume of the ordered items, the delivery area and any additional services (delivery to apartment entrance, etc.). The following delivery pricelist is applied. All prices are in Bulgarian Lev (BGN) with included VAT. 1. Delivery of samples and small 3. Additional service - Delivery to packages door-to-door up to 20 kg. apartment entrance. If you need assistance by us for delivering the goods to your apartment, Kilograms Zone 1 - Zone 11 this is additionaly paid handling service, which you can request by 0 - 1 kg. -

Annual Report of Bulgarian Biodiversity Foundation 2008

BBF Annual Report 2008 ANNUAL REPORT OF BULGARIAN BIODIVERSITY FOUNDATION 2008 1 BBF Annual Report 2008 CONTEXT The main topic of the political analysis at the end of the year was that in 2008 nothing special happened in Bulgaria and this is the good news. According to us many things happened in Bulgaria this year and no one of them is good news. 2008 was “the year of the scandals” with no political act or political figure unconnected to corruption, infringement of the laws or negligence of the undertaken commitments. Our second year as an EU member was marked with the sign of the increasing discontent from European Parliament, as well as the Bulgarian citizens. The European Commission asked Bulgaria to freeze several thousands millions euros funding under the European Union's pre-accession programmes SAPARD and PHARE. The only reaction of the government was to accuse EC in double standard. The attempts of the Prime-minister Stanishev to convince EC of the state efforts were shattered from the unprecedented and public accusation of corruption made by Mr. Barroso – “I should tell you that we will not allow some people to play political games with the Euro funds.” In the field of environment and applying of the European environmental legislation there is some good news. Scientists and NGOs could be proud with the evaluation of the EC for the establishment of Natura 2000 network with its 114 Special Protection Areas (SPAs) in accordance with the Bird Directive and 229 Sites of Community Importance (SCI) in accordance with the Habitat Directive. -

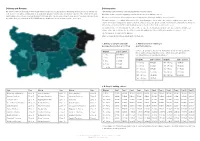

Regional Disparities in Bulgaria Today: Economic, Social, and Demographic Challenges

REGIONAL DISPARITIES IN BULGARIA TODAY: ECONOMIC, SOCIAL, AND DEMOGRAPHIC CHALLENGES Sylvia S. Zarkova, PhD Student1 D. A. Tsenov Academy of Economics – Svishtov, Department of Finance and Credit Abstract: To accelerate Bulgaria's economic development taking into account the specific characteristics of their regions is a serious challenge for the local governments in the country. The ongoing political and economic changes require a reassessment of the country's economic development. The aim of this study was to analyse the disparities among Bulgaria’s regions (de- fined in accordance with the Nomenclature of Territorial Units for Statistics (NUTS)) by assessing the degree of economic, social and demographic chal- lenges they face and performing a multivariate comparative analysis with sets of statistically significant indicators. The analysis clearly outlines the bounda- ries of the regional disparities and the need to improve the country’s regional and cohesion policies. Key words: regional policy, differences, NUTS, taxonomic develop- ment measure. JEL: J11, O18, R11. * * * 1 Е-mail: [email protected] The author is a member of the target group of doctoral students who participated in activities and training within the implementation of project BG05M2OP001-2.009-0026-C01 ‘Capacity development of students, PhD students, post-doctoral students and young scientists from the Dimitar A. Tsenov Academy of Economics - Svishtov for innovative scientific and practical Research in the field of economics, administration and management’ funded by the Operational Program ‘Science and Education for Smart Growth’ co-financed by the Structural and Investment Funds of the European Union. The paper won first place in the ‘Doctoral Students’ category of the national competition ‘Young Economist 2018’.