Liver Dysfunction in TB-Diabetic and TB Non-Diabetic Patients Admitted

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Checking Blood Sugar Levels

Checking Blood Sugar Levels People with type 1 diabetes (T1D) must check their blood sugar (glucose) levels throughout the day using a blood glucose meter. The meter tells them how much glucose is in their blood at that particular moment. Based upon the reading, they take insulin, eat, or modify activity to keep blood sugars within their target range. Regularly checking blood sugar levels is an essential part of T1D care. Methods for Checking Blood Sugar Levels Checking, or testing, involves taking a drop of blood, usually from the fingertip, and placing it on a special test strip in a glucose meter. Blood sugar meters are easy to use, and even young children often learn quickly how to do their own blood sugar checks. In order to properly manage their diabetes, individuals with T1D check their blood sugar levels several times per day. For example, they may test before eating lunch and before strenuous exercise. Blood sugar levels are measured in milligrams per deciliter (mg/dL). A normal blood sugar level is between 70 and 120 mg/dL. Keeping blood sugar levels within this range may be difficult in children with diabetes. Therefore, an individual's doctor may adjust the target range (for example, 80-180 mg/dL). However, people with diabetes can't always maintain blood sugar levels within the target range, no matter how hard they try. A person's varying schedules and eating habits, as well as the physical changes that occur as they grow, can send blood sugar levels out of range for no apparent reason. -

Hba1c Matters

HbA1c Matters What is HbA1c? The HbA1c reading reveals your average blood sugar level over the past three months. When blood sugar levels are high, sugar attaches to the red blood cells. The HbA1c monitors how much sugar is attached to the red blood cells, which have a lifespan of about 3 months. The HbA1c reading is therefore able to show what your average blood sugar levels have been in the last 3 months. The units we report HbA1c in are changing, and in the future you will see it reported as a whole number rather than a percentage. Both units are given below. Why does it matter? HbA1c levels are linked with risk of diabetes complications, with higher readings increasing the chance of problems. This is illustrated in the graph below. 15 13 Retinopathy 11 Nephropathy Relative 9 Risk 7 Neuropathy 5 Microalbuminuria 3 1 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Previous method % 42 53 64 75 86 97 108 New IFCC method HbA1c The graph shows the risk of complications associated with diabetes including retinopathy (eye damage that can lead to blindness), nephropathy (kidney damage that can lead to kidney failure and a need for dialysis), neuropathy (damage to the nerves) and microalbuminuria (protein in the urine which is associated with kidney damage). When HbA1c levels are below 7.5% or 58 mmol/mol, the risk of each of these complications is very low – approximately equivalent to people who do not have diabetes. The risk of each complication rises increasingly steeply as HbA1c levels rise above 7.5% or 58 mmol/mol. -

Deducing Serum Fructosamine Levels from the Fasting Blood Glucose Value: a Preliminary Study H

http://doi.org/10.4038/cjms.v44i2.4863 Deducing serum fructosamine levels from the fasting blood glucose value: a preliminary study H. Perns' The Ceylon Journal of Medical Science 2001; 44:25-28 Abstract However, recent studies have shown that fructosamine (glycated protein) can be used to The determination of glycated serum proteins differentiate between well and poorly stabilized (fructosamine) has become an accepted index for diabetics (1). Fructosamines are stable keto- assessing the metabolic situation in diabetic amines formed by a non-enzymatic reaction patients. The current study describes an alternative between a sugar and a protein. It has been known to measurement of fructosamine level, viz., to that a number of proteins, e.g., haemoglobin, predict the serum fructosamine based on the serum proteins, membrane proteins, protein in glucose concentration in fasting plasma. A cross- the lens of eye etc. are glycated by a non- sectional prospective study was performed on 44 enzymatic reaction and forms a stable fructo non-diabetic, 38 impaired glucose tolerance and samine (isoglucosamine) which depends on the 38 diabetic subjects attending clinics at Colombo glucose concentration. The glycated serum South Teaching Hospital. Fasting plasma glucose proteins form very quickly with changes in the and corresponding serum fructosamine glucose concentration than the glycated concentrations were determined on all subjects. haemoglobin (HbA ) formed in the erythrocytes. Fructosamine showed a positive linear correlation ]c The largest fraction, about 60-70% of glycated of r2 = 0.85 with the fasting plasma glucose serum proteins, consists of albumin with a half- concentrations. Regression equation relating to life in serum about 2-3 weeks (2). -

Liquid QC™ Bilirubin Control

Hemoglobin A1C Reagent ® INTENDED USE FOR IN VITRO DIAGNOSTIC USE No special additives or preservatives other than anticoagulants are required. Collect Hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) Reagent is intended for the quantitative determination of venous blood with EDTA using aseptic technique. Hemoglobin A1c in human blood. INTERFERING SUBSTANCES SUMMARY Bilrubin to 50 mg/dl, ascorbic acid to 50 mg/dl, triglycerides to 2000 mg/dl, The determination of HbA1c is most commonly performed for the evaluation of carbamylated Hb to 7.5 mmol/L and acetylated Hb to 5.0 mmol/L do not interfere with glycemic control in diabetes mellitus. HbA1c values provide an indication of glucose this assay. See also the LIMITATION SECTION. levels over the preceding 4-8 weeks. A higher HbA1c value indicates poorer glycemic control. PROCEDURE Throughout the circulatory life of the red cell, HbA1c is formed continuously by the Materials provided adduction of glucose to the N-terminal of the hemoglobin beta chain. This process, 85621 R1 1 x 30 mL which is non-enzymatic, reflects the average exposure of hemoglobin to glucose over R2A 1 x 9.5 mL an extended period. In a classical study, Trivelli, et al, (10.1) showed HbA1c in diabetic subjects to be elevated 2-3 fold over the levels found in normal individuals. R2B 1 x 0.5 mL Several investigators have recommended HbA1c serve as an indicator of metabolic R3 1 x 200 mL control of the diabetic, since HbA1c levels approach normal levels for diabetics in metabolic control. (10.2,10.3,10.4) HBA1c has been defined operationally as the “fast Materials required but not provided fraction” hemoglobins (HbA , A , A ) that elute first during column chromatography 1a 1b 1c 1. -

89 Abstract a Study of Gamma

89 A STUDY OF GAMMA-GLUTAMYLTRANSFERASE (GGT) IN TYPE 2 DIABETES MELLITUS AND ITS RISK FACTORS Shrawan Kumar Meena1, Alka Meena2, Jitendra Ahuja3, Vishnu Dutt Bohra1 1Dept. of Biochemistry, Jhalawar Medical College, And Hospital, Jhalawar (Raj) ijcrr 2Dept. of Biochemistry, Lady Harding medical college and hospital, New Delhi Vol 04 issue 11 3Dept. of Biochemistry, Geetanjali Medical College and Hospital, Udaipur (Raj) Category: Research Received on:18/04/12 Revised on:29/04/12 E-mail of Corresponding Author: [email protected] Accepted on:09/05/12 ABSTRACT Objective — To study the Serum gamma-glutamyltransferase (GGT), other liver derived enzymes and lipid profile in patients of type 2 Diabetes mellitus (DM) and find out the any correlation of liver derived enzymes with diabetic related risk factor and association between enzyme level and blood sugar level in diabetic and non diabetic subjects. Research Design and Methods— This is a cross-sectional prospective study in 60 cases of type 2 DM randomly selected from medical wards of a tertiary care hospital and 30 age, sex matched controls. Blood sugar, Serum gamma-glutamyl transferase (GGT), other liver enzymes like SGOT, SGPT, ALP, Lipid profile, BMI, waist circumference and prevalence of obesity and hypertension were assessed. To define the type 2 Diabetes mellitus (DM) we used revised criteria of ADA, 1997. Results— GGT, Fasting Blood glucose and BMI increased statistically significant (p<0.00l) in type 2 DM subjects when compared with the control subjects. Statistically significant difference (p<0.05) in SGPT was found in subjects of type 2 DM. Comparison of other parameters like BP, alkaline phosphates, PL, TG and VLDL were also found Statistically significant difference (p<0.01). -

Relationship Between Diabetes Mellitus and Serum Uric Acid Levels

Int. J. Pharm. Sci. Rev. Res., 39(1), July – August 2016; Article No. 20, Pages: 101-106 ISSN 0976 – 044X Review Article Relationship between Diabetes Mellitus and Serum Uric Acid Levels J. Sarvesh Kumar*, Vishnu Priya V1, Gayathri R2 *B.D.S I ST YEAR, Saveetha Dental College, 162, P.H road, Chennai, Tamilnadu, India. 1Associate professor, Department of Biochemistry, Saveetha Dental College, 162, P.H Road, Chennai, Tamilnadu, India. 2Assistant professor, Department of Biochemistry, Saveetha Dental College, 162, P.H Road, Chennai, Tamilnadu, India. *Corresponding author’s E-mail: [email protected] Accepted on: 03-05-2016; Finalized on: 30-06-2016. ABSTRACT The aim of the study is to review the association between diabetes Mellitus and serum uric acid levels. The objective is to review how uric acid level is related to diabetes Mellitus. Diabetes is an increasingly important disease globally. New data from IDF showed that there are 336 million people with diabetes in 2011 and this is expected to rise to 552 million by 2030. It has been suggested that, diabetic epidemic will continue even if the level of obesity remains constant. The breakdown of foods high in protein into chemicals known as purines is responsible for the production of uric acid in the body. If there is too much of uric acid in the body it causes variety of side effects. Thus identifying risk factors of serum uric acid is required for the prevention of diabetes. The review was done to relate how serum uric acid level is associated with the risk of diabetes. -

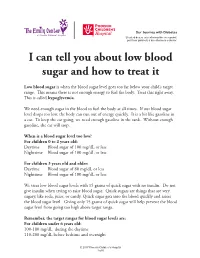

I Can Tell You How the Donor Will Be Determined

Our Journey with Diabetes Si usted desea esta información en español, por favor pídasela a su enfermero o doctor. I can tell you about low blood sugar and how to treat it Low blood sugar is when the blood sugar level goes too far below your child’s target range. This means there is not enough energy to fuel the body. Treat this right away. This is called hypoglycemia. We need enough sugar in the blood to fuel the body at all times. If our blood sugar level drops too low, the body can run out of energy quickly. It is a bit like gasoline in a car. To keep the car going, we need enough gasoline in the tank. Without enough gasoline, the car will stop. When is a blood sugar level too low? For children 0 to 2 years old: Daytime Blood sugar of 100 mg/dL or less Nighttime Blood sugar of 100 mg/dL or less For children 3 years old and older: Daytime Blood sugar of 80 mg/dL or less Nighttime Blood sugar of 100 mg/dL or less We treat low blood sugar levels with 15 grams of quick sugar with no insulin. Do not give insulin when trying to raise blood sugar. Quick sugars are things that are very sugary, like soda, juice, or candy. Quick sugar gets into the blood quickly and raises the blood sugar level. Giving only 15 grams of quick sugar will help prevent the blood sugar level from going too high above target range. Remember, the target ranges for blood sugar levels are: For children under 6 years old: 100-180 mg/dL during the daytime 110-200 mg/dL before bedtime and overnight © 2017 Phoenix Children’s Hospital 1 of 6 For children between 6 and 12 years old: 90-180 mg/dL during the daytime 100-180 mg/dL before bedtime and overnight For teens between 13 and 19 years old: 90-130 mg/dL during the daytime 90-150 mg/dL before bedtime and overnight The levels for blood sugars at night are slightly higher because it can be hard to feel and respond to symptoms of low blood sugar when we are sleeping. -

Hormones: Definition

Hormones: definition - a chemical signal released into body fluids. Generally this regulates or causes a specific action. Usually, only specific cells known as target cells will respond, but some hormones can affect many different systems: A simple example: Adrenal gland -> epinephrine -> raises blood sugar level, increases heart rate, generally increases metabolic activity. [target cells include liver, heart, lungs.] Endocrine glands - glands that secrete hormones. The human body has lots, only some of which will be covered here [Fig., not in text, but similar to 45.10, p. 981]. (Also, exocrine glands -> essentially hormones that are released outside body e.g., pheromones). See table on p. 987 for a list of hormones in humans (not exhaustive). Hypothalamus/pituitary: Pituitary - a small gland at base of brain. Composed of two parts [Figs. 45.14, p. 985] Anterior pituitary [Fig. 45.17, p. 988] - directly controlled by the hypothalamus (through a portal vein system). - synthesizes and secretes hormones depending on whether or not a “releasing hormone” or “inhibiting hormone” is produced by the hypothalamus. All hormones made here have at least a “releasing hormone”. - hormones produced here include: - GH - growth hormones. - Prolactin - stimulates mammary glands. - FSH/LH - affects testes or ovaries. - Thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH). - ACTH - stimulates adrenal cortex. - MSH - stimulates melanocytes (affects pigments - not in your text). - endorphins - regulates pain receptors in brain (dulls pain). - keep this list in mind - some of these will come up again later. Posterior pituitary [Fig. 45.15, p. 986] - stores and releases two hormones that are manufactured by hypothalamus: - oxytocin - induces contractions of uterus (next lecture) - ADH - Anti Diuretic Hormone - discussed in our previous lecture. -

Parathyroid (4) Large Intestine

1. A very high level of calcium in the blood suggests a malfunction of the (1) liver (2) pancreas (3) parathyroid (4) large intestine 2. In humans, which substance is directly responsible for controlling the calcium levels of the blood? (1) adrenaline (2) insulin (3) parathormone (4) thyroxin 3. The maintenance of proper blood sugar level involves the storage of excess sugar in the (1) salivary glands (2) stomach (3) pancreas (4) liver 4. The hormone TSH stimulates the production of (1) thyroxin (2) insulin (3) estrogen (4) testosterone 5. An example of the maintenance of homeostasis in humans is the action of glucagon and insulin in regulating the (1) temperature of the body (3) excretion of urine from the bladder (2) concentration of blood sugar (4) secretion of thyroxin 6. Secondary sex characteristics in males are regulated by (1) amylase (2) acetylcholine (3) testosterone (4) estrogen 7. The graph below represents the level of glucose in a student's blood from 11:00 a.m. until 10:00 p.m. At 3:30 p.m. the student ran in a cross-country meet, and at 5:30 p.m. the student ate dinner. Which hormones were primarily responsible for producing some of the changes in blood sugar level between 4:30 p.m. and 8:00 p.m.? (1) insulin and glucagon (3) parathormone and TSH (2) estrogen and progesterone (4) adrenaline and FSH 8. Pituitary growth hormone can affect cells in various parts of the human body because the hormone is secreted directly into (1) glandular ducts (2) muscle tissue (3) the bloodstream (4) the digestive tract 9. -

DIABETES MELLITUS Connie J

Northwest Community Healthcare Paramedic Education Program DIABETES MELLITUS Connie J. Mattera, M.S., R.N., EMT-P Reading assignment: Aehlert Vol. 1 pp 957 – 962 SOP: Diabetic/Glucose Emergencies (p. 26); Peds Diabetic / Glucose Emergencies (p. 76); D10% dosing chart (p.100) OBJECTIVES Upon completing the assigned readings, class and homework questions, each participant will independently do the following with at least an 80% degree of accuracy and no critical errors: 1. Define diabetes mellitus. 2. Discuss the functions of the islets of Langerhans, including the formation and function of insulin, glucagon, and somatostatin. 3. Describe how the body normally metabolizes and controls blood glucose. 4. Compare and contrast the classifications of diabetes including the pathophysiology, onset, clinical presentation and potential complications of type 1, type 2, and gestational diabetes. 5. Identify the classifications, names, and actions of oral diabetes medications and the various types of insulin. 6. Outline the epidemiology and causes of DKA. 7. Sequence the development of dehydration and acidosis in DKA. 8. Separate the signs and symptoms of DKA into those that reflect acidosis and those that reflect dehydration. 9. Differentiate DKA and hyperglycemic, hyperosmolar, non-ketotic syndrome (HHNS). 10. List the precipitating factors for HHNS. 11. Discuss the pathophysiology of hypoglycemia. 12. List the signs and symptoms of hypoglycemia. 13. Describe the body's compensatory mechanisms to hypoglycemia. 14. Anticipate the effects of elevated insulin levels in the body. 15. Give examples of the long-term effects of hyperglycemia on the body systems, including the kidneys, heart and blood vessels, eyes, and nervous system. 16. -

Effects of Aerobic Training on FBS, Hba1c, Fructosamine and Plasma Lipid Profile in Male with Type 2 Diabetes

Available online at www.ijmrhs.com International Journal of Medical Research & ISSN No: 2319-5886 Health Sciences, 2016, 5, 6:27-33 Effects of aerobic training on FBS, HbA1C, Fructosamine and plasma lipid profile in male with type 2 diabetes 1Akbar Ghalavand, 2Rooholah Rezaee, 3Alinaghi Gholami, 4Reza Mahmoodkhanikooshkaki and 5Mohammad Hosein Mahmoudnejad 1Sama Technical and Vocational Training College Tehran Branch (Andisheh) Islamic Azad University, Tehran, Iran 2Sama Technical and Vocational Training College Tehran Branch (Andisheh) Islamic Azad University, Tehran, Iran 3Lecturer, Department of Physical Education and Sport Sciences, University of Payame noor, Iran 4Dezful University of Medical Sciences, Dezful, Iran 5Sama Technical and Vocational Training College Tehran Branch (Andisheh) Islamic Azad University, Tehran, Iran _____________________________________________________________________________________________ ABSTRACT Regular exercise represents an effective strategy to prevent and treat type 2 Diabetes.The present study examined the effects of aerobic exercise on glycemic control and serum lipid profile in men with type 2 diabetes.20 men with type 2 diabetes (age:45.05 ± 3.8) were randomly divided into aerobic exercise group (n=10) and control group(n=10). Exercise Group participated in aerobic training program at 50 -70 % HRR for 8 weeks and 3 sessions per week. Fasting blood sugar (FBS),Fructosamine, HbA1C, Triglyceride (TG), cholesterol (TC), high density lipoproteins (HDL), low density lipoproteins (LDL) and very low -

Controlling Your Blood Glucose Level Is Important for Everyone, Whether

Controlling your blood Hypoglycemia MANAGING YOUR BLOOD Low levels of blood glucose (hypoglycemia) can be caused glucose by malnutrition, increased exercise, not eating enough food, kidney failure or liver disease. Diabetics can suffer level is SUGAR from hypoglycemia if they take too much insulin. Common symptoms include cold sweats, confusion, blurry vision, important fatigue, headache, hunger, trembling and rapid heart rate. Blood sugar refers to the amount of glucose in your blood. for Knowing and managing your blood sugar level can help Diabetics can manage low blood sugar by eating a snack or prevent a variety of health problems. drinking a beverage containing sugar. Non-diabetics with everyone, severe hypoglycemia may require immediate medical whether Why Is It Important? attention, as it can cause blindness, coma or even death. Glucose is the sugar your body uses for energy, Those without diabetes can also change their diet to help you’re metabolism and proper brain function. The body needs prevent episodes of low blood sugar. Your doctor may blood sugar to stay at a relatively consistent level, and suggest eating small, frequent meals with complex diabetic or regulates this level through hormones. An anabolic carbohydrates, fiber and fat—and avoiding simple sugars, hormone called insulin decreases the level of glucose, while alcohol and fruit juice. Also be sure to eat meals at regular not. catabolic hormones raise your level. Too high or too low intervals, and balance extra exercise with sufficient blood sugar can cause many severe health problems. additional food. Diabetes occurs when your blood glucose is too high, as a result of your body not producing or absorbing enough insulin.