Mutual Image Impacts of Events and Host Destinations: What We Know from Prior Research

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Horton Wins All-Around Title at Õ 09 Visa

WOMEN SLOAN WINS WOMEN’S ALL-AROUND TITLE At ’09 VISA CHAMPIONSHIPS Photos by John Cheng ridget Sloan, a 2008 Olympic team silver medalist from Sharp’s Gymnastics, won her first U.S. all-around title at the 2009 Visa Championships at the American Airlines Center in Dallas. Sloan, who was third after the first day of competition, came from behind to win the title with a score 117.550. “It feels great to win the Visa Championships,” said Sloan. “The first day didn’t go as planned, but today went well.” Sloan’s top scores of the two-day competition were for her Yurchenko double full vault (15.000), and her floor routine which includes a one-and-a-half to triple twist for her first pass (15.050). 2008 Olympic Team alternate Ivana Hong of WOGA finished a Kytra Hunter Mackenzie Caquatto close second in the all-around at 117.250. Hong’s top scores were on vault for her Yurchenko double (15.250) and her beam routine that included a flip flop series into a double pike dismount (15.200). WOGA’s Rebecca Bross, who led the competition after day one, landed in third place with an all-around score of 116.600. Bross had !" #$% a rough bar routine on day two that pulled her down in the rankings. Her top score of the competition was a 15.300 for her double twisting Yurchenko vault and a 15.050 for her jam-packed bar routine on the first day of competition. Kytra Hunter of Hill’s Gymnastics finished fourth in the all-around with 113.750 and took third on floor, showing a huge piked double Arabian and double layout. -

Minutes of the 101St FAI General Conference (Rhodes; 2007)

101st Annual General Conference Minutes of Working Sessions Held at the Capsis Hotel Rhodes, Greece 12 th and 13 th October 2007 FEDERATION AERONAUTIQUE INTERNATIONALE 101 st ANNUAL GENERAL CONFERENCE MINUTES OF THE WORKING SESSIONS HELD ON FRIDAY 12th AND SATURDAY 13th OCTOBER 2007 AT CAPSIS HOTEL, RHODES, GREECE IN THE CHAIR .......................................Mr. Pierre PORTMANN, FAI President ACTIVE MEMBERS OF FAI : FAI ACTIVE MEMBERS REPRESENTED WITH VOTING RIGHTS HEADS OF DELEGATIONS AUSTRALIA ...........................................Mr. Henk MEERTENS AUSTRIA ...............................................Dr. Alois ROPPERT BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA ..............Mr. Omer KULIC BULGARIA ............................................Mr. Nick KALTCHEV CANADA ................................................Mr. Jack HUMPHREYS CHILE ....................................................Mr. Julio SUBERCASEAUX MAC-GILL CROATIA ...............................................Mr. Tonci PANZA CYPRUS ................................................Mr. Demetrakis HADJIDEMETRIOU CZECH REPUBLIC ................................Mr. Jiri DODAL DENMARK .............................................Mr. Aksel C. NIELSEN ESTONIA ...............................................Mr. Urmas USKA FINLAND ...............................................Mr. Hannu HALONEN FRANCE ................................................Mr. Jean-Michel CONSTANT GERMANY .............................................Mr. Günter BERTRAM GREECE ................................................Mr. -

The World Games Orienteering Event

July 16 – 26, 2009 THE WORLD GAMES ORIENTEERING EVENT Bulletin 3 - Event Information 1. General information about The World Games 2009 in Kaohsiung, Chinese Taipei The International World Games Association (IWGA) has awarded the 2009 World Games to the City of Kaohsiung, Chinese Taipei. Orienteering is one of the 31 sports included in the program of these games. The Chinese Taipei Orienteering Association has been entrusted with the organization of the orienteering events and is pleased to welcome the world’s elite orienteers to this major event. The World Games The World Games is an international multi-sport event held every fourth year under the auspices of the IWGA. The World Games is organised under the patronage of the International Olympic Committee (IOC). The IOF has been a member of the International World Games Association since 1995. In 2001 orienteering made its debut on the program of The World Games held in Akita, Japan. The programme of The 8th World Games 2009 Kaohsiung includes competitions in 26 official sports and in 5 sports on the invitational program - altogether more sports than ever before. More than 5000 athletes and officials are expected to participate in the competitions that will take place at 24 different venues in Kaohsiung and Kaohsiung County. The 8th World Games 2009 Kaohsiung will get under way with the Opening Ceremony at the Main Stadium on Thursday, July 16, 2009. The athletes and officials will parade by country under their national flags. The closing ceremony will take place at the Main Stadium on Sunday, 26th July, 2009. For detailed information on the overall sports program, please consult The World Games 2009 Kaohsiung website at www.worldgames2009.tw The Chinese Taipei Orienteering Association (CTOA) is overall responsible for the orienteering events of the games. -

After Action Report

2009 Special Olympics World Winter Games All-Star Fan Program After Action Report Presented by: April 17, 2009 All-Star Fan Program 2009 Special Olympics World Winter Games After Action Reports Provided by The CE Group April 17, 2009 Table of Contents 1. Cover Letter 2. Program Overview 3. Organizational Chart 4. Report Card 5. Recommendations 6. Operational Area Evaluations a. Accommodations and Food & Beverage l. May I Serve You b. Administration and Operations Center m. Opening Ceremony Parade of Athletes c. Airport Gate Greets n. Opening Ceremony Photography d. Awards Presentations o. Program Operational Plan e. Coffee Walks p. Project Director f. Credentialing q. Technology g. Database Management r. Tracks h. Décor Design Plan Including Signage s. Transportation i. Dine-Around t. Volunteers & Guides j. Guest Management u. Welcome Center k. Hotel Contracts Program Overview All‐Star Fans Program The All‐Star Fans program is the hospitality program for top Special Olympics Global Supporters. The Program is organized and executed by Special Olympics International, with cooperation from the 2009 Special Olympics World Winter Games, Idaho, USA. • Participants include Celebrities, Government Leaders, Corporate and Individual supporters and other dignitaries • Size of Program is 250 – 300 people (120 – 150 groups or delegations) • Custom‐designed schedule of events centered around the principles of engagement, education and service • Wave program: – Opening Wave 2/6 – 2/9 – Sun Valley Experience 2/9 – 2/13 – Medaling and Competition Wave 2/11 – 2/14 • Hotels – Host: The Grove, Boise, Idaho – Overflow: Hotel 43, Boise, Idaho – Sun Valley: The Lodge and The Inn, Sun Valley, Idaho 2009 ALL STAR FAN Program Chairman On Site Management Tim Shriver President & COO Brady Lum Project Advisor GOC COO Overall Program Games Advisor Janet Holliday Kirk Miles Lee Todd Peter Wheeler (CE) 1. -

DUKLA Bulletin 2009 Eng.Pdf

Military Sport Centre Editorial The Military Sport Centre DUKLA does not stand only for a tradition of more than forty years of great sport achieve- ments, it is also a brand of international significance and a guarantee of quality and top results into the future. It joins the majority of the best Slovak individual sportsmen and provides the best possible conditions within the whole Slo- vakia. My relationship with DUKLA’s colours and emblem is a very intimate one. I have spent here more than twen- ty years as an active competitor and so I could get closely acquainted with the obvious quality of the most successful Slovak sport club. During my active professional career, I was honoured to wear the state coat of arms on my jersey and I felt always proud, when I could promote the country of the honest, hearty and hardworking people by means Peter Korčok of sport. I highly appreciate the top sportsmen and their world’s achievements, as I appreciate fair-play and also the challenging work of coaches and support teams. Every day, I do see how demanding, responsible but also necessary is the constant care for and support of sport with DUKLA’s emblem. Therefore I highly appreciate and support those who were helping DUKLA in the past and also those who are still contributing to its prosperity and quality of work at every level. We, in the Military Sport Centre DUKLA, will give our best to work in such a way that would make our annual summing-up more successful than the previous one. -

Annual Report 2009/2010

Annual Report 2009/2010 Published SEPTEMBER 2011 CONTENTS FROM THE PRESIDENT 1 IWAS EXECUTIVE BOARD 3 President Presentation Report 4 Vice President Report 7 Secretary General Report 9 Honorary Treasurer Report 12 Sport Science and Medical Report 14 VISION AND MISSION 18 ORGANIZATIONAL STRUCTURE 18 ABOUT IWAS 19 SPORTS ACTIVITIES REPORT 20 Wheelchair Fencing 21 IWAS Athletics 26 Electric Wheelchair Hockey 27 MEMBER COUNTRY LISTING 30 CONTACT DETAILS 31 PRESIDENT’S MESSAGE Federation in the position of Secretary General. To help prepare for this Maura had assisted us in reorganizing HQ staff, promoting Charmaine Hooper to the position as Head of Operations. In 2009 we added two dedicated and hardworking individuals Stacey Ashwell, Sports and Finance Administrator and Morwenna Breen-Haynes, Membership Services. This team makes for a strong HQ as they work very well together. We have also established an Executive Management It has been almost four years since I Committee, including Maura, Karl have been able to join many of Vilhelm Nielsen, and Bob Paterson you at an IWAS General Assembly and me, which meets by or the World Games. I anxiously conference call at least monthly to look forward to see you all at the direct the Federation’s programs. I General Assembly held in also meet with the Head of conjunction with the World Games Operations weekly by conference in Sharjah. call to assist in guiding the Operations. These last two years have been one of adjustment for IWAS. In mid As always IWAS supports a full 2010, Maura Strange, our Executive calendar of event to fulfil our Director, Secretary General and mission to maximizing sport torch bearer for IWAS and the opportunities for athletes to Paralympic Movement for over 18 compete and develop. -

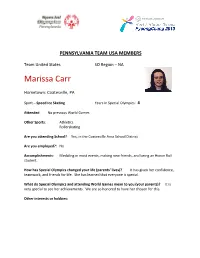

Marissa Carr

PENNSYLVANIA TEAM USA MEMBERS Team United States SO Region – NA Marissa Carr Hometown: Coatesville, PA Sport – Speed Ice Skating Years in Special Olympics: 4 Attended: No previous World Games Other Sports: Athletics Rollerskating Are you attending School? Yes, in the Coatesville Area School District Are you employed?: No Accomplishments: Medaling in most events, making new friends, and being an Honor Roll student. How has Special Olympics changed your life (parents’ lives)? It has given her confidence, teamwork, and friends for life. She has learned that everyone is special. What do Special Olympics and attending World Games mean to you (your parents)? It is very special to see her achievements. We are so honored to have her chosen for this. Other interests or hobbies: Team United States SO Region – NA Kevin M. Conley Hometown: Pittsburgh, PA Field of Service – Medical Years in Special Olympics: 15 Attended: Yes, World Games 2011 in Athens, Greece Other Sports: Are you employed?: Yes, by the University of Pittsburgh as Assistant Dean for Undergraduate Studies, School of Health and Rehabilitation Sciences Accomplishments: Being a part of Team USA for the World Summer Games in Athens was an experience of a lifetime. How has Special Olympics changed your life? Being a part of Special Olympics has helped me to see there are no barriers to reaching one’s goals, only challenges that make us all stronger. What do Special Olympics and attending World Games mean to you? It means I get to go (again!) to a world class competition with some of the best athletes in the USA. -

Taiwan's Marginalized Role in International Security: Paying a Price

JANUARY 2015 A Report of the CSIS Freeman Chair in China Studies AUTHORS Bonnie S. Glaser Jacqueline A. Vitello 1616 Rhode Island Avenue NW | Washington, DC 20036 t. 202.887.0200 | f. 202.775.3199 | www.csis.org ROWMAN & LITTLEFIELD Lanham • Boulder • New York • Toronto • Plymouth, UK 4501 Forbes Boulevard, Lanham, MD 20706 t. 800.462.6420 | f. 301.429.5749 | www.rowman.com Cover photo: Taiwan aid workers provide disaster relief in the Philippines after Typhoon Haiyan (2013). Credit: International Headquarters S.A.R., Taiwan. Taiwan’s Marginalized Role ISBN 978-1-4422-4059-9 Ë|xHSLEOCy240599z v*:+:!:+:! in International Security Paying a Price Blank Taiwan’s Marginalized Role in International Security Paying a Price AUTHORS Bonnie S. Glaser Jacqueline A. Vitello A Report of the CSIS Freeman Chair in China Studies January 2015 ROWMAN & LITTLEFIELD Lanham • Boulder • New York • Toronto • Plymouth, UK About CSIS For over 50 years, the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) has worked to develop solutions to the world’s greatest policy challenges. Today, CSIS scholars are providing strategic insights and bipartisan policy solutions to help decisionmakers chart a course toward a better world. CSIS is a nonprofit or ga ni za tion headquartered in Washington, D.C. The Center’s 220 full- time staff and large network of affiliated scholars conduct research and analysis and develop policy initiatives that look into the future and anticipate change. Founded at the height of the Cold War by David M. Abshire and Admiral Arleigh Burke, CSIS was dedicated to finding ways to sustain American prominence and prosperity as a force for good in the world. -

The Promotional Strategies of 2009 Kaohsiung World Games

Georgia Southern University Digital Commons@Georgia Southern Association of Marketing Theory and Practice Association of Marketing Theory and Practice Proceedings 2010 Proceedings 2010 Preparation for an International Sport Event: The Promotional Strategies of 2009 Kaohsiung World Games Steve Shih-Chia Chen Morehead State University, [email protected] Ronald Dick Duquesne University, [email protected] Ashley McNabb Morehead State University Yin-chu Tseng Kaohsiung Medical University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/amtp- proceedings_2010 Part of the Marketing Commons Recommended Citation Chen, Steve Shih-Chia; Dick, Ronald; McNabb, Ashley; and Tseng, Yin-chu, "Preparation for an International Sport Event: The Promotional Strategies of 2009 Kaohsiung World Games" (2010). Association of Marketing Theory and Practice Proceedings 2010. 11. https://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/amtp-proceedings_2010/11 This conference proceeding is brought to you for free and open access by the Association of Marketing Theory and Practice Proceedings at Digital Commons@Georgia Southern. It has been accepted for inclusion in Association of Marketing Theory and Practice Proceedings 2010 by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@Georgia Southern. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Preparation for an International Sport Event: The Promotional Strategies of 2009 Kaohsiung World Games Steve Chen, Morehead State University Ron Dick, Duquesne University Ashley McNabb, Morehead State University Yin-chu Tseng, Kaohsiung Medical University, Taiwan ABSTRACT This study presented administrative and marketing-related information on Kaohsiung City’s preparation for the 2009 World Games. The presented information was allocated through an extensive literature review on secondary sources, personal interviews, and observations from fall of 2008 to summer of 2009. -

Volume 6, Issue 1, March 2019 Articles

The Athens Journal of Sports (ATINER) (ATINER) Volume 6, Issue 1, March 2019 Articles Front Pages STEVE CHEN, YUN-KUANG LEE, CHIEH DER DONGFANG, CAO-YEN CHEN & TSUNG-CHIH CHIU Taiwanese Residents’ Perceived Social, Economic, Recreational and Political Benefits for Hosting the 2017 Universiade Games STEVEN CARNEY & HAL WALKER Recreation, Sport and an Aging Population MAŁGORZATA TOMECKA The Elite of “Kalos Kagathos” in Poland NIKOLAY IVANTCHEV & STANISLAVA STOYANOVA Athletes and Non-Athletes’ Life Satisfaction i ATHENS INSTITUTE FOR EDUCATION AND RESEARCH A World Association of Academics and Researchers 8 Valaoritou Str., Kolonaki, 10671 Athens, Greece. Tel.: 210-36.34.210 Fax: 210-36.34.209 Email: [email protected] URL: www.atiner.gr (ATINER) Established in 1995 (ATINER) Mission ATINER is a World Non-Profit Association of Academics and Researchers based in Athens. ATINER is an independent Association with a Mission to become a forum where Academics and Researchers from all over the world can meet in Athens, exchange ideas on their research and discuss future developments in their disciplines, as well as engage with professionals from other fields. Athens was chosen because of its long history of academic gatherings, which go back thousands of years to Plato’s Academy and Aristotle’s Lyceum. Both these historic places are within walking distance from ATINER‟s downtown offices. Since antiquity, Athens was an open city. In the words of Pericles, Athens“…is open to the world, we never expel a foreigner from learning or seeing”. (“Pericles‟ Funeral Oration”, in Thucydides, The History of the Peloponnesian War). It is ATINER‟s mission to revive the glory of Ancient Athens by inviting the World Academic Community to the city, to learn from each other in an environment of freedom and respect for other people‟s opinions and beliefs. -

Visible Or Invisible Games? a Critique on the Future of the World Games

PHYSICAL CULTURE AND SPORT STUDIES AND RESEARCH DOI: 10.2478/v10141-010-0003-3 Visible or Invisible Games? A Critique on the Future of the World Games Li-Hong (Leo) Hsu International Olympic and Multicultural Studies Centre (CEO), Da-Yeh University, Taiwan ABSTRACT As the crowded calendar of world sport and the increasing competition between sporting festivals is likely to affect more second-tier global sporting festivals than the Olympic Games (Cashman 2004, p. 134), this paper attempts to answer a few questions concerning the future of the World Games, i.e. a multi-sport mega event. The first and primary question is whether it is worthwhile to host the World Games. In this paper reasoned justification will be provided with a critical eye. Furthermore, questions will be raised about the when and particularly about the where. The content of the World Games’ programs will be briefly discussed and critically evaluated as well. As an example the author will use the 2009 World Games in Kaohsiung, Taiwan for discussion. KEYWORDS World Games, mega event, Kaohsiung I. Introduction For the world of mega-sporting-events, many would agree that the Olympic Games have drawn the most attention, because of their ultimate level of athletic performance. One can also note that there is constant evolution and change in mega-sporting-events around us. With the hope of achieving political, cultural, and economic benefits mega-sporting-events have become a useful means for many countries. With these objectives in mind, the process of bidding for an internationally well-known mega-sporting-event has become very competitive ever since. -

The 2009 TEAM USA Has Again Successfully Defended Their

George Pickard, former President of FIRS Inline Hockey and current Chairman of USA Roller Sports Inline Hockey Committee, has through team interviews provided the following assessment of the 2009 year’s American men’s triumphal inline hockey campaigns: XV FIRS MEN’S INLINE HOCKEY WORLD CHAMPIONSHIP The 2009 MEN’S TEAM USA has again successfully defended their International Federation of Roller Sports (FIRS) World Inline Hockey Championship in Varese, Italy, July 6 through 11, 2009. Eight new players formed the 13 man roster after a come-back win last year restored their title in Dusseldorf, Germany. Team USA was not afforded the favorite’s designation this year, as one might expect of the defending champion, largely due to the complete absence of veteran stars that have carried the USA team through the past decade and a half since the organization by FIRS of world inline hockey. The strong national teams of the Czech Republic, Switzerland, Canada and France presented formidable obstacles for these young Americans to overcome. The Czech inline hockey team, as usual, was liberally sprinkled with ice hockey veterans recruited from their nucleus of hockey talent which radiates throughout the professional leagues of Europe and into the NHL of North America. The Swiss and Canadians teams consisted of veteran players who considered hockey victories their natural right and looked upon such accomplishments as mere fulfillment of their national heritage. All three of these teams have previously won FIRS World Inline Hockey Championships. And there was another serious contender, France, which has been twice runner-up at the World Championships and has the best pure inline roller hockey development program in Europe.