Dorchester WW1 Resources Guide Copy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Book of Dovecotes

A B O O K O F D O V EC OT E S ’e BY A R THU R Oil éfOOKE A UTHOR OF “ THE FOREST OF D EAN ” T . N . FOUL IS PU BLISHE , R LOND ON E DI N BU GH 69' BO , R , ST ON Thi s wo rk i s publi she d by F O U L IS T . N . LONDON ! 1 Gre at R ussell St e e t W . C . 9 r , EDINBU R GH 1 5 Fre d e ri ck S tre e t BOSTON 1 5 A shburton Place ' L e R a P/i llz s A en t ( y r j , g ) A nd ma a so be o d e re d th ou h the o o wi n a enci e s y l r r g f ll g g , whe re the work m ay be exami ne d A U STR A LA S IA ! The O ord U ni ve si t re ss Cathe d a ui di n s xf r y P , r l B l g , 20 F i nd e s Lane M e bourne 5 l r , l A NA D A ! W . C . e 2 Ri ch m o nd Stre e t . We st To onto C B ll , 5 , r D NM A R K ! A aboule va rd 28 o e nh a e n E , C p g (N 'r r ebr os B oglza n d e l) Publis hed i n N ovem é e r N in e teen H un dr e d a n d Pr in ted i n S cotla nd by T D E d z n é u r /z . -

Dorset and East Devon Coast for Inclusion in the World Heritage List

Nomination of the Dorset and East Devon Coast for inclusion in the World Heritage List © Dorset County Council 2000 Dorset County Council, Devon County Council and the Dorset Coast Forum June 2000 Published by Dorset County Council on behalf of Dorset County Council, Devon County Council and the Dorset Coast Forum. Publication of this nomination has been supported by English Nature and the Countryside Agency, and has been advised by the Joint Nature Conservation Committee and the British Geological Survey. Maps reproduced from Ordnance Survey maps with the permission of the Controller of HMSO. © Crown Copyright. All rights reserved. Licence Number: LA 076 570. Maps and diagrams reproduced/derived from British Geological Survey material with the permission of the British Geological Survey. © NERC. All rights reserved. Permit Number: IPR/4-2. Design and production by Sillson Communications +44 (0)1929 552233. Cover: Duria antiquior (A more ancient Dorset) by Henry De la Beche, c. 1830. The first published reconstruction of a past environment, based on the Lower Jurassic rocks and fossils of the Dorset and East Devon Coast. © Dorset County Council 2000 In April 1999 the Government announced that the Dorset and East Devon Coast would be one of the twenty-five cultural and natural sites to be included on the United Kingdom’s new Tentative List of sites for future nomination for World Heritage status. Eighteen sites from the United Kingdom and its Overseas Territories have already been inscribed on the World Heritage List, although only two other natural sites within the UK, St Kilda and the Giant’s Causeway, have been granted this status to date. -

Old Sandpitts House Broadwindsor • Dorset

OLD SANDPITTS HOUSE BROADWINDSOR • DORSET OLD SANDPITTS HOUSE BROADWINDSOR • DORSET A superb family house with an indoor swimming pool in a highly desirable location, standing in magnificent gardens and grounds which are a wonderful feature of the property, including a series of spring fed lakes. Additional lots include a detached lodge cottage with large modern barn and garaging; a detached cottage with private drive; and a separate paddock. Beaminster 4 miles, Crewkerne 4 miles (London Waterloo from 2 hours 30 minutes) • Bridport 8 miles, Yeovil 15 miles Sherborne 20 miles, Exeter Airport 35 miles (All times and distances are approximate) Lot 1 – Old Sandpitts House: Ground floor: Entrance hall Sitting room Dining room Study Library Kitchen / breakfast room Utility room Boot room WC Indoor swimming pool with shower room and WC First floor: Master bedroom and bathroom 6 further bedrooms 2 shower rooms Family bathroom Formal gardens Playroom Gym Greenhouse Orchard Vegetable garden Spring-fed lakes About 10 acres (4.08 hectares) Lot 2 - Old Sandpitts Lodge & Barn: Kitchen Dining room Sitting room 3 bedrooms Family bathroom 4 car garage General purpose barn: Inspection pit Workshop Studio 2 stables About 0.75 acres (0.30 hectares) Lot 3 – Paddock: Separate paddock of about 3.53 acres (1.43 hectares) Lot 4 - Old Sandpitts Cottage: Kitchen Sitting room 2 bedrooms Family bathroom Garden About 0.44 acres (0.18 hectares) Knight Frank LLP Knight Frank LLP 55 Baker Street 15 Cheap Street, Sherborne London W1U 8AN Dorset DT9 3PU [email protected] [email protected] Tel: +44 (0)20 7861 1528 Tel: +44 (0)1935 812 236 www.knightfrank.co.uk Situation and Amenities • Old Sandpitts House is the notable house of Sandpit, an historic hamlet a mile north of Broadwindsor in the rolling Dorset countryside. -

Evolution in the Rock Dove: Skeletal Morphology Richard F. Johnston

The Auk 109(3):530-542, 1992 EVOLUTION IN THE ROCK DOVE: SKELETAL MORPHOLOGY RICHARD F. JOHNSTON Museumof NaturalHistory and Department of Systematicsand Ecology, 602 DycheHall, The Universityof Kansas,Lawrence, Kansas 66045, USA ABSTRACT.--Domesticpigeons were derived from Rock Doves (Columbalivia) by artificial selection perhaps 5,000 ybp. Fetal pigeon populations developed after domesticsescaped captivity; this began in Europe soon after initial domesticationsoccurred and has continued intermittently in other regions. Ferals developed from domesticstocks in North America no earlier than 400 ybp and are genealogicallycloser to domesticsthan to European ferals or wild RockDoves. Nevertheless, North American ferals are significantlycloser in skeletalsize and shapeto Europeanferals and Rock Doves than to domestics.Natural selectionevidently has been reconstitutingreasonable facsimiles of wild size and shape phenotypesin fetal pigeonsof Europeand North America.Received 17 April 1991,accepted 13 January1992. Man, therefore, may be said to have been and southwestern Asia; this is known to be true trying an experiment on a gigantic scale; in more recent time (Darwin 1868; N. E. Bal- and it is an experimentwhich nature dur- daccini, pers. comm.). Later, pigeons escaping ing the long lapse of time has incessantly captivity either rejoined wild colonies or be- tried [Darwin 1868]. came feral, and are now found in most of the world (Long 1981). European,North African, Of the many kinds of animals examined for and Asiatic ferals may have historiesof -

Memorials of Old Dorset

:<X> CM \CO = (7> ICO = C0 = 00 [>• CO " I Hfek^M, Memorials of the Counties of England General Editor : Rev. P. H. Ditchfield, M.A., F.S.A. Memorials of Old Dorset ?45H xr» MEMORIALS OF OLD DORSET EDITED BY THOMAS PERKINS, M.A. Late Rector of Turnworth, Dorset Author of " Wimborne Minster and Christchurch Priory" ' " Bath and Malmesbury Abbeys" Romsey Abbey" b*c. AND HERBERT PENTIN, M.A. Vicar of Milton Abbey, Dorset Vice-President, Hon. Secretary, and Editor of the Dorset Natural History and Antiquarian Field Club With many Illustrations LONDON BEMROSE & SONS LIMITED, 4 SNOW HILL, E.C. AND DERBY 1907 [All Rights Reserved] TO THE RIGHT HONOURABLE LORD EUSTACE CECIL, F.R.G.S. PAST PRESIDENT OF THE DORSET NATURAL HISTORY AND ANTIQUARIAN FIELD CLUB THIS BOOK IS DEDICATED BY HIS LORDSHIP'S KIND PERMISSION PREFACE editing of this Dorset volume was originally- THEundertaken by the Rev. Thomas Perkins, the scholarly Rector of Turnworth. But he, having formulated its plan and written four papers therefor, besides gathering material for most of the other chapters, was laid aside by a very painful illness, which culminated in his unexpected death. This is a great loss to his many friends, to the present volume, and to the county of for Mr. Perkins knew the as Dorset as a whole ; county few men know it, his literary ability was of no mean order, and his kindness to all with whom he was brought in contact was proverbial. After the death of Mr. Perkins, the editing of the work was entrusted to the Rev. -

Update on Takeaways and Businesses Around Bridport

LIST OF RESOURCES IN THE GREATER BRIDPORT AREA FOR VOLUNTEERS AND THE SELF-ISOLATING CURRENT AS OF 22ND MARCH 2020 National Online Pharmacies (Repeat Subscriptions) Echo Prescription www.echo.co.uk 02080688067 Pharmacy2u www.pharmacy2u.co.uk 0113 265 0222 Local Pharmacies Monday to Saturday: 8:30am to 4:30pm Six customers permitted to queue (9:30 to 4:30 from Monday 23rd March) West Street, for the pharmacy but only two Boots Bridport permitted at a time at the counter. Sunday: 11am to 2pm Free NHS prescription delivery available. 01308 422475 https://www.boots.com/ Monday to Friday: 8:30am to 6:30pm For the safety staff, only five Saturday: 8:45am to 12:30pm Bridport Medical customers allowed inside at a time Sunday: closed Lloyds Centre, West for prescriptions. Please use the Allington, Bridport outside door to queue. A member of staff will let you in and out. 01308 424350 http://www.lloydspharmacy.com/ Monday to Friday: 9am to 5:30pm Saturday: 9am to 1pm East Street, Free NHS prescription delivery Sunday: closed Well+ Bridport available. Currently implanting a two customer maximum at a time. 01308 422100 https://www.well.co.uk/ Cafés, Pubs and Restaurants Baboo Salwayash Gelato ice cream delivered direct Delivery only 01308 488629 or email to your door or company. [email protected] Fridays and Saturdays, 6pm to Takeaway and +44 1308 807002 Beach & Barnicott South Street, 10pm. Cash only. delivery or via website Bridport Vegetarian. Order dinner for a neighbour in need. £5 per meal – BearKat Bistro Barrack Street, extra donations welcome – through Delivery only bearkatsupper@outlook. -

12 November for December Issue. [email protected]

WELCOME! It’s great to have The White Lion roaring back into life again, in the hands of our new landlords, Vikki and Spike. We wish them all the very best of luck – and it’s down to us, as a community, to support them. We might not all be drinkers but having a thriving pub in the centre of the village is good for all of us. If you haven’t already done so, please pop in and say hello. I’m pleased to say that the challenge I threw down in the last issue about getting the village pump going again is beginning to bear fruit. Watch this space, as they say. And the Brownies are planning to put a tub of plants next to the pump, so that’ll brighten things up a bit. Again, there’s lots going on in the village and the surrounding area this month. Don’t forget the Fireworks at Bernards’ Place on 4 November. It’s free admission to this event, but the Jubilee Group does appreciate your donations, as fireworks aren’t cheap. Food will be served from 6pm but please don’t leave it too late to get your hot dog or burger, as one visitor did last year and then complained that it was ‘disgusting’ that the food had run out before they got there at 7pm. The fireworks will last for approximately half an hour, so please keep your pets indoors. I always leave Radio Four on for mine. Thanks again to Julie Steele for the cover photo – Julie, the magazine would look very bare without you! Margery Hookings Date for final copy: 12 November for December issue. -

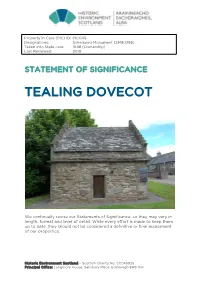

Tealing Dovecot Statement of Significance

Property in Care (PIC) ID: PIC045 Designations: Scheduled Monument (SM90298) Taken into State care: 1948 (Ownership) Last Reviewed: 2019 STATEMENT OF SIGNIFICANCE TEALING DOVECOT We continually revise our Statements of Significance, so they may vary in length, format and level of detail. While every effort is made to keep them up to date, they should not be considered a definitive or final assessment of our properties. Historic Environment Scotland – Scottish Charity No. SC045925 Principal Office: Longmore House, Salisbury Place, Edinburgh EH9 1SH © Historic Environment Scotland 2020 You may re-use this information (excluding logos and images) free of charge in any format or medium, under the terms of the Open Government Licence v3.0 except where otherwise stated. To view this licence, visit http://nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open- government-licence/version/3 or write to the Information Policy Team, The National Archives, Kew, London TW9 4DU, or email: [email protected] Where we have identified any third party copyright information you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned. Any enquiries regarding this document should be sent to us at: Historic Environment Scotland Longmore House Salisbury Place Edinburgh EH9 1SH +44 (0) 131 668 8600 www.historicenvironment.scot 1 HISTORIC ENVIRONMENT SCOTLAND STATEMENT OF SIGNIFICANCE TEALING DOVECOT CONTENTS 1 Summary 3 1.1 Introduction 3 1.2 Statement of significance 3 2 Assessment of values 4 2.1 Background 4 2.2 Evidential values 5 2.3 Historical values 6 2.4 Architectural and artistic values 8 2.5 Landscape and aesthetic values 8 2.6 Natural heritage values 8 2.7 Contemporary/use values 8 3 Major gaps in understanding 8 4 Associated properties 8 5 Keywords 8 Bibliography 9 APPENDICES Appendix 1: Timeline 9 Appendix 2: General history of doocots 11 2 1 Summary 1.1 Introduction Tealing Dovecot is located beside the Home Farm in the centre of Tealing Village, five miles north of Dundee on the A90 towards Forfar. -

Beacon Ward Beaminster Ward

As at 21 June 2019 For 2 May 2019 Elections Electorate Postal No. No. Percentage Polling District Parish Parliamentary Voters assigned voted at Turnout Comments and suggestions Polling Station Code and Name (Parish Ward) Constituency to station station Initial Consultation ARO Comments received ARO comments and proposals BEACON WARD Ashmore Village Hall, Ashmore BEC1 - Ashmore Ashmore North Dorset 159 23 134 43 32.1% Current arrangements adequate – no changes proposed Melbury Abbas and Cann Village BEC2 - Cann Cann North Dorset 433 102 539 150 27.8% Current arrangements adequate – no changes proposed Hall, Melbury Abbas BEC13 - Melbury Melbury Abbas North Dorset 253 46 Abbas Fontmell Magna Village Hall, BEC3 - Compton Compton Abbas North Dorset 182 30 812 318 39.2% Current arrangements adequate – no Fontmell Magna Abbas changes proposed BEC4 - East East Orchard North Dorset 118 32 Orchard BEC6 - Fontmell Fontmell Magna North Dorset 595 86 Magna BEC12 - Margaret Margaret Marsh North Dorset 31 8 Marsh BEC17 - West West Orchard North Dorset 59 6 Orchard East Stour Village Hall, Back Street, BEC5 - Fifehead Fifehead Magdalen North Dorset 86 14 76 21 27.6% This building is also used for Gillingham Current arrangements adequate – no East Stour Magdalen ward changes proposed Manston Village Hall, Manston BEC7 - Hammoon Hammoon North Dorset 37 3 165 53 32.1% Current arrangements adequate – no changes proposed BEC11 - Manston Manston North Dorset 165 34 Shroton Village Hall, Main Street, BEC8 - Iwerne Iwerne Courtney North Dorset 345 56 281 119 -

STATEMENT of PERSONS NOMINATED Date of Election : Thursday 7 May 2015

West Dorset District Council Authority Area - Parish & Town Councils STATEMENT OF PERSONS NOMINATED Date of Election : Thursday 7 May 2015 1. The name, description (if any) and address of each candidate, together with the names of proposer and seconder are show below for each Electoral Area (Parish or Town Council) 2. Where there are more validly nominated candidates for seats there were will be a poll between the hours of 7am to 10pm on Thursday 7 May 2015. 3. Any candidate against whom an entry in the last column (invalid) is made, is no longer standing at this election 4. Where contested this poll is taken together with elections to the West Dorset District Council and the Parliamentary Constituencies of South and West Dorset Abbotsbury Name of Candidate Home Address Description (if any) Name of Proposer and Seconder Invalid DONNELLY 13 West Street, Abbotsbury, Weymouth, Company Director Arnold Patricia T, Cartlidge Arthur Kevin Edward Patrick Dorset, DT3 4JT FORD 11 West Street, Abbotsbury, Weymouth, Wood David J, Hutchings Donald P Henry Samuel Dorset, DT3 4JT ROPER Swan Inn, Abbotsbury, Weymouth, Dorset, Meaker David, Peach Jason Graham Donald William DT3 4JL STEVENS 5 Rodden Row, Abbotsbury, Weymouth, Wenham Gordon C.B., Edwardes Leon T.J. David Kenneth Dorset, DT3 4JL Allington Name of Candidate Home Address Description (if any) Name of Proposer and Seconder Invalid BEER 13 Fulbrooks Lane, Bridport, Dorset, Independent Trott Deanna D, Trott Kevin M Anne-Marie DT6 5DW BOWDITCH 13 Court Orchard Road, Bridport, Dorset, Smith Carol A, Smith Timothy P Paul George DT6 5EY GAY 83 Alexandra Rd, Bridport, Dorset, Huxter Wendy M, Huxter Michael J Yes Ian Barry DT6 5AH LATHEY 83 Orchard Crescent, Bridport, Dorset, Thomas Barry N, Thomas Antoinette Y Philip John DT6 5HA WRIGHTON 72 Cherry Tree, Allington, Bridport, Dorset, Smith Timothy P, Smith Carol A Marion Adele DT6 5HQ Alton Pancras Name of Candidate Home Address Description (if any) Name of Proposer and Seconder Invalid CLIFTON The Old Post Office, Alton Pancras, Cowley William T, Dangerfield Sarah C.C. -

West Dorset, Weymouth & Portland Local Plan 2015

West Dorset, Weymouth & Portland Local Plan 2015 WEST DORSET, WEYMOUTH AND PORTLAND LOCAL PLAN 2011-2031 Adopted October 2015 Local Plan West Dorset, Weymouth & Portland Local Plan 2015 Contents CHAPTER 1. Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 3 CHAPTER 2. Environment and Climate Change.................................................................................. 19 CHAPTER 3. Achieving a Sustainable Pattern of Development .......................................................... 57 CHAPTER 4. Economy ......................................................................................................................... 81 CHAPTER 5. Housing ......................................................................................................................... 103 CHAPTER 6. Community Needs and Infrastructure ......................................................................... 113 CHAPTER 7. Weymouth .................................................................................................................... 133 CHAPTER 8. Portland ........................................................................................................................ 153 CHAPTER 9. Littlemoor Urban Extension ......................................................................................... 159 CHAPTER 10. Chickerell ...................................................................................................................... 163 -

Directions To: Laverstock Farm

Directions to: Laverstock Farm Postal Address: Laverstock House Laverstock Bridport Dorset DT6 5PE Tel: 01308 867 688 / 07766 522 798 / 07957 398 505 Please beware that some satellite navigation systems take you to a lane at the back of the farm. Depending from where you start, you should first head for Crewkerne or Bridport Directions from Crewkerne: 1. Leave Crewkerne via South Street (A356 toward the Train Station) and stay on the road for approximately 2 miles. You will go through Misterton. 2. After Misterton, turn right on the A3066 (signed Bridport) and stay on the road for approximately 2.5 miles. You will go through Mosterton. 3. Shortly after leaving Mosterton, take a sharp right on a bend (B3164) towards Broadwindsor. 4. After just over 1 mile, you will enter Broadwindsor. Keep left on the one way system and turn left at the T Junction – then turn immediately right onto the B3162. 5. Stay on the B3162 for approximately 1.5 miles and then turn right at the first small cross roads. There are four trees on each corner and it is signed Blackney. 6. After about 0.5 miles on a sharp left hand bend turn right down a small lane signed Laverstock. If you go round a very sharp left hand bend you have gone too far. 7. Drive over the first cattle grid and keep left. Continue down the drive with the post and rail fence on your left, over the second cattle grid and the house is on your right. 8. Drive past the house and park on the right by a stone wall.