In Defence of the Professor Who Publishes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2017 Chicxulub Revealed

THE UNIVERSITY TEXAS OF AUSTIN AT JACKSON• SCHOOL GEOSCIENCES OF 2017 NEWSLETTER• Newsletter2 017 Chicxulub Revealed A first look at rocks from the crater left by the asteroid that wiped out non-avian dinosaurs WELCOME Dear Alumni and Friends he devastation that Hurricane Harvey brought to Texas communities in August was a tragic reminder of how vital it is to understand our planet and T its processes. Shortly after the hurricane struck, our scientists, through our Rapid Response program, began to conduct research to understand how Harvey has impacted the coast and offshore Gulf of Mexico. This research will help determine the best ways to deal with many coastal issues in the aftermath of the storm, and how we might better prepare for such events in the future. You can read more about the mission on page 18. Rapid response efforts on the effects of abrupt, catastrophic geoscience events COVER: GRANITE FROM THE PEAK RING OF provide critical science that can benefit society. This is what we strive to do here at the THE CHICXULUB CRATER FORMED BY THE Jackson School of Geosciences. This year’s Newsletter holds some tremendous examples. ASTEROID STRIKE THAT WIPED OUT ALL NON- AVIAN DINOSAURS I’d like to draw your attention to the story on page 58 about the scientific coring mission led by Peter Flemings to bring back samples of methane hydrate from ABOVE: MEMBERS OF THE JACKSON beneath the Gulf of Mexico. This is a cutting-edge research project on a potential SCHOOL-LED TEAM CORING FOR SAMPLES OF METHANE HYDRATE IN THE GULF OF MEXICO future energy source that very few schools in the world would be able to mount. -

Science Policy Bulletin, Volume 2 Number 5. INSTITUTION Battelle Memorial Inst., Columbus, Ohio

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 042 598 SE 007 869 AUTHOR Brainard, Robert W., Ed. TITLE Science Policy Bulletin, Volume 2 Number 5. INSTITUTION Battelle Memorial Inst., Columbus, Ohio. Columbus Labs. PUB DATE Oct 69 NOTE 66p. EDRS PRICE EDRS Price MF-$0.50 HC-$3.40 DESCRIPTORS *Annotated Bibliographies, Federal Legislation, Financial Support, Foreign Policy, *Government Role, Natural Resources, *Policy Formation, *Scientific Research, Socioeconomic Influences, *Technology ABSTRACT This bimonthly bulletin reports annotations of current literature on science and public policy. Coverage includes both "policy for science..!, and "science for policy" in the areas of engineering, technical and narrowly specialized publications. Its purpose.is to aid persons who study, formulate, or implement public policy related to science by alerting them to new additions to tilt. science policy literature. Documents are listed under the headings of (1) General, (2) Science, Domestic Problems and National Goals, (3) Needs and Allocation of Resources for Science,(4) National R & D Programs,(5) Science, Education, and the University, (6) Science Management and Policy-Making Bodies, (7) Science, Foreign Affairs, and National Defense, and (8) Science Policy in Foreign Countries. The 109 documents are listed under°one of these categories. Cross-indexing is not used. Major meetings and other events in the area are also reported. (RR) Vol. 2 Number 5 October, 1969 U.S. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH, EDUCATION & WELFARE OFFICE OF EDUCATION THIS DOCUMENT HAS BEEN REPRODUCED EXACTLY AS RECEIVED FROM THE PERSON OR ORGANIZATION ORIGINATING IT. POINTS OF VIEW OR OPINIONS STATED DO NOT NECESSARILY REPRESENT OFFICIAL OFFICE OF EDUCATION POSITION OR POLICY. Science Policy Bulletin Battelle Memorial Institute SCIENCE POLICY BULLETIN The Bulletin, published bimonthly, reports the current literature in the area of science and public policy. -

Temple Israel Rabbi’S & President’S Messages Tigers and Strawberries President’S Message Friends — the Following Is an Excerpt from Rabbi Mars’S Kol

Temple Israel Rabbi’s & President’s Messages Tigers and Strawberries President’s Message Friends — The following is an excerpt from Rabbi Mars’s Kol Nidre Sermon. You can read her full sermon on our I am so grateful for the Temple Israel teams that website, https://www.templeisrael.org/rabbis-message. meet regularly to discuss goals and help us grow One day while wandering through the wilderness, our congregation. Our Education Team kicks off A woman stumbles upon a tiger. Aghast, she 2020 with a column about their work. I am runs and runs until the tiger chases her to the grateful for their leadership! very edge of a cliff. She stares down and spies a Amy Weisbach — Amy Weisbach Rabbi Sharon Mars vine. Desperate to save herself, she grips the vine Temple Israel President and lowers herself over the precipice. The tiger above roars, and for the moment she can breathe. We Jews are fortunate. And for many reasons. One of which is that When suddenly, she hears another roar…there are tigers below her we get an opportunity to push our restart buttons not just once, but as well. two times a year! Our entry into 5780 may feel like a distant memory, but the ringing in of 2020 is likely fresh in our minds. As fear grips her chest she realizes that the vine is slowly being Perhaps you are among the 60% of Americans who declare a New gnawed away by the sharp teeth of a tiny little mouse. Just when she Year’s resolution. Maybe your resolution aims for ‘more’ - learn thinks all is lost, the woman sees a beautiful bunch of ripe something new, increase patience with your children, make more strawberries nestled in a nearby clump of grass jutting out from the connections with others. -

Mars Pathfinder

NASA Facts National Aeronautics and Space Administration Jet Propulsion Laboratory California Institute of Technology Pasadena, CA 91109 Mars Pathfinder Mars Pathfinder was the first completed mission events, ending in a touchdown which left all systems in NASAs Discovery Program of low-cost, rapidly intact. developed planetary missions with highly focused sci- The landing site, an ancient flood plain in Mars ence goals. With a development time of only three northern hemisphere known as Ares Vallis, is among years and a total cost of $265 million, Pathfinder was the rockiest parts of Mars. It was chosen because sci- originally designed entists believed it to as a technology be a relatively safe demonstration of a surface to land on way to deliver an and one which con- instrumented lander tained a wide vari- and a free-ranging ety of rocks robotic rover to the deposited during a surface of the red catastrophic flood. planet. Pathfinder In the event early in not only accom- Mars history, sci- plished this goal but entists believe that also returned an the flood plain was unprecedented cut by a volume of amount of data and water the size of outlived its primary North Americas design life. Great Lakes in Pathfinder used about two weeks. an innovative The lander, for- method of directly mally named the entering the Carl Sagan Martian atmos- Memorial Station phere, assisted by a following its suc- parachute to slow cessful touchdown, its descent through and the rover, the thin Martian atmosphere and a giant system of named Sojourner after American civil rights crusader airbags to cushion the impact. -

Meyer, Michael Mars Exploration and Mars Sample Return

Michael Meyer Lead Scientist Planetary Science Decadal Survey Mars Exploration & Mars Sample Return Panel on Mars, Nov 2, 2020 1 Why Mars? Mars is a habitable planet and has the potential to answer fundamental questions about our Solar System • The potential for life • A geological record of the first billion years of planetary evolution • A drastically changing climate through time • A compelling target for Human Exploration Mars Exploration Program Analysis Group Goals Human Life Climate Geology Exploration I. Determine if Mars ever supported life III. Understand II. Understand the origin and I. Determine if IV. Prepare for the processes evolution of Mars ever human and history of Mars as a supported, or exploration climate on Mars geological still supports life system Life I. Determine if Mars A. Search for evidence of life in environments that have a high potential for habitability and preservation of biosignatures. ever supported, or B. Assess the extent of abiotic organic chemical evolution. still supports, life. Climate II. Understand the A. Characterize the state and controlling processes of the present-day climate of Mars under the current orbital configuration. processes and B. Characterize the history and controlling processes of Mars’ climate in the recent past, history of climate under different orbital configurations. on Mars. C. Characterize Mars’ ancient climate and underlying processes. Geology III. Understand the A. Document the geologic record preserved in the crust and investigate the processes that have created and modified that record. origin and evolution B. Determine the structure, composition, and dynamics of the interior and how it has of Mars as a evolved. -

Rabbi's & President's Messages

Rabbi’s & President’s Messages The Challenge of Joy President’s Message Purim is upon us! And with Purim comes the Dear Temple Israel Family– call, “Mi shenich’nas Adar marbim b’simcha! Whoever enters into the month of As we enter the final phase of our Adar should be happy!” I recently spoke to a friend of the campaign, we continue to be congregation who told me that if I noticed this encouraged by the generous person’s more frequent absence from activities, it participation of this congregation. If you is because of the deep sadness this person has have completed your commitment, I been experiencing lately. The last few years for Rabbi Sharon Mars Patti Shorr, offer you my sincere gratitude on behalf this person’s life has been riddled with family Temple Israel President stresses and mental health struggles. So much of this person’s time of the building committee, the Board of and resources have out of necessity needed to be poured singularly Trustees of the the Temple and the into making sure that their children were okay and their marriage Temple Israel Foundation. Your generosity is stayed afloat. “That’s why you haven’t seen me in synagogue, inspirational and will benefit our members and future Rabbi,” this person said. “And even if I could manage to muster the members!. We have accomplished great things with this energy to come to shul, I don’t think I could be around other people’s joy, or they could handle being around my sadness.” Shuvu campaign, including gifts from over 200 member Happiness can be hard to come by in this life, and households. -

Newsletter Archive the Skyscraper February 2021

the vol. 48 no. 02 Skyscraper February 2021 AMATEUR ASTRONOMICAL SOCIETY OF RHODE ISLAND 47 PEEPTOAD ROAD NORTH SCITUATE, RHODE ISLAND 02857 WWW.THESKYSCRAPERS.ORG In This Issue: A Walking Tour of Optical History- 2 President’s Message Artifacts and Anecdotes from the 3 Observing the Winter Circle 5 The Sun, Moon & Astronomical Lyceum Planets in February 6 The Hyades: More than An Online Presentation by John Briggs Meets the (Bull's) Eye Saturday, February 6, 7:00pm EST via Zoom 8 NASA Night Sky Notes: Contact Steve Hubbard ([email protected]) for 8 Landing On Mars: A Tricky Feat! Zoom Meeting link and information. 9 Requiem for a Telescope Our forefathers in optics allowed a revo- students remain aware of these inspirations 10 Cluster & Nebula in Auriga: lutionary ascendancy of American astrono- -- they are all lessons to be learned. NGC 1893 & IC 410 my in the 19th and early 20th centuries. The John W. Briggs of Magdalena, New Mex- 12 From the Archives Astronomical Lyceum in New Mexico, orig- ico, has lived and worked at far-ranging ob- inally built in 1936 as a theater and gymna- servatories in various technical capacities, 13 Hank Renaud Memorial sium, now houses a collection of telescopes, including Mount Wilson, Yerkes, National Book Sale optics, archives, and literature from this as- Solar, Maria Mitchell, Venezuelan Nation- cendancy. Its volunteer staff find the artifacts al, Chamberlin, and South Pole Station. In 13 January Reports and associated history surprisingly engag- the 1980s he was an assistant editor at Sky 14 Astronomical League ing for visitors of all interest levels. -

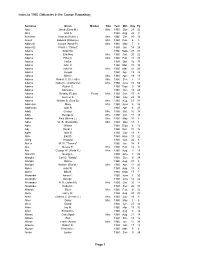

Index to 1960 Obituaries in the Canton Repository Page 1

Index to 1960 Obituaries in the Canton Repository Surname Given Maiden Title Year Mth Day Pg Abel Jacob (Clara M.) Mrs. 1960 Dec 28 32 Abel John A. 1960 Aug. 29 9 Ackelson Thomas (Ruth I.) Mrs. 1960 Dec 10 10 Ackert Edward (Patience) Mrs. 1960 Feb. 6 8 Adamcik Joseph (Anna P.) Mrs. 1960 May 7 6 Adametz Frank J. "Chant" 1960 Jan. 14 29 Adams Bright M. 1960 Sept. 28 28 Adams Ella May Mrs. 1960 Oct. 20 22 Adams Ethel A. Mrs. 1960 Feb. 15 20 Adams Helen 1960 Oct. 16 37 Adams John H. 1960 Mar. 31 39 Adams John W. Mrs. 1960 Mar. 21 26 Adams Joseph 1960 Apr. 13 24 Adams Minnie Mrs. 1960 Apr. 19 15 Adams Robert C. (Celestie) Mrs. 1960 Dec 3 11 Adams Robert L. (Catherine) Mrs. 1960 June 15 56 Adams Robert S. 1960 Sept. 9 14 Adams Samuel L. 1960 Jan. 19 20 Adams Schalto (Retta) Peary Mrs. 1960 Oct. 15 8 Adams Sumner S. 1960 July 28 10 Adams William B. (Zula B.) Mrs. 1960 Aug. 23 34 Adamson Mary Mrs. 1960 June 5 36 Addleman John R. 1960 Apr. 6 23 Addy George Mrs. 1960 Oct. 16 38 Addy George D. Mrs. 1960 Oct. 17 18 Adkins Paul (Wilma L.) Mrs. 1960 May 10 8 Adler WR(DllMW. R. (Della May ) Mrs. 1960 May 17 8 Adler William 1960 Sept. 6 16 Ady Oscar J. 1960 Dec. 31 12 Agler John B. 1960 July 19 8 Ahle Earl D. 1960 Nov. 18 22 Ailing Howard 1960 Oct. -

Edison Pettit Papers: Finding Aid

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/tf9q2nb3w2 No online items Edison Pettit Papers: Finding Aid Processed by Ronald S. Brashear in March 1998. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens Manuscripts Department 1151 Oxford Road San Marino, California 91108 Phone: (626) 405-2191 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.huntington.org © 1998 The Huntington Library. All rights reserved. Edison Pettit Papers: Finding Aid mssPettit papers 1 Overview of the Collection Title: Edison Pettit Papers Dates (inclusive): 1920-1969 Collection Number: mssPettit papers Creator: Pettit, Edison, 1889-1962. Extent: 6 boxes (3,100 pieces) Repository: The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens. Manuscripts Department 1151 Oxford Road San Marino, California 91108 Phone: (626) 405-2191 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.huntington.org Abstract: This collection contains the papers of astronomer Edison Pettit (1889-1962), who was on the staff of the Mount Wilson and Palomar Observatories. The correspondence is chiefly with other astronomers in the United States and deals with astronomy in general including Pettit's work at Mount Wilson, telescopes, and ultraviolet light research. The rest of the collection is made up of manuscripts, notes, notebooks and printed items. Language: English. Access Open to qualified researchers by prior application through the Reader Services Department. For more information, contact Reader Services. Publication Rights The Huntington Library does not require that researchers request permission to quote from or publish images of this material, nor does it charge fees for such activities. The responsibility for identifying the copyright holder, if there is one, and obtaining necessary permissions rests with the researcher. -

Spectrophotometric Modeling of Soils and Rocks at the Opportunity Landing Site

Lunar and Planetary Science XXXVII (2006) 1480.pdf SPECTROPHOTOMETRIC MODELING OF SOILS AND ROCKS AT THE OPPORTUNITY LANDING SITE. J.R. Johnson1, R.E. Arvidson2, J.F. Bell III3, R. Deen4, W. Farrand5, W. Grundy6, E. Guinness2, M. Johnson3, K.E. Herkenhoff1, M. Lemmon7, F. Seelos IV8, J. Soderblom3, S. Squyres3, and the Athena Science Team, 1U.S. Geological Survey, 2255 N. Gemini Dr., Flagstaff, AZ 86001, [email protected], 2Washington University, St. Louis, MO, 3Cornell University, Ithaca, NY, 4Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Pasadena, CA, 5Space Sciences Institute, Boulder, CO, 6Lowell Observatory, Flagstaff, AZ, 7Texas A&M University, College Station, TX, 8Applied Physics Laboratory, Laurel, MD. Introduction: The Panoramic Camera (Pancam) on incorporating local facet tilts for ROIs. Hapke the Opportunity Mars Exploration Rovers [1] models were run using Henyey-Greenstein (HG) acquired multispectral reflectance observations of phase functions to determine the asymmetry outcrop rocks and spherule-rich soils at different parameter (ξ) for a 1-term HG, and the b (asymmetry incidence, emission, and phase angles (0-155°) that parameter) and c (backscattering fraction) parameters were used for photometric modeling to constrain the for a 2-term HG. All models included the single albedo and physical properties of the surface scattering albedo (w) and macroscopic roughness materials. Nominal filters covered wavelengths of parameter (θ ). For data sets lacking observations at 432 nm, 601 nm, 753 nm, and 1003 nm, with a stereo phase angles < 20° the opposition effect width (h) filter selected as either 436 nm or 754 nm. and amplitude (B0) were set to zero. A reduced chi- Observations. -

Unusual Marine Ecosystem in the Flooded Crater of Ushisher Volcano

MARINE ECOLOGY PROGRESS SERIES Published July 19 Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. REVIEW Unusual marine ecosystem in the flooded crater of Ushisher volcano A. V. Zhirmunsky, V. G.Tarasov Intistute of Marine Biology, Far Eastern Branch, Academy of Sciences of the USSR, Vladivostok 690032, USSR ABSTRACT: This paper reviews investigations of a manne ecosystem In Kraternaya Bight (Yanluch Island, Kurile Islands) which has arisen and is functioning under the influence of gaso-hydrothermal vents of the Ushishir volcano. The concentrations of reduced sulphur compounds and a number of metals in the vents are 2 to 3 orders of magnitude higher than in seawater around the island. Together with photosynthesis of algae, chernosynthetic bacteria play an essential part in primary production. Extreme chemical conditions in the outlets of vents have left a mark on the composition of communities and in peculiarities of certain species. Concentrations of some metals are so high that ecosystems of Kraternaya Bight can be considered as a model of sea territory with a high degree of industrial pollution. At the request of the Institute of Marine Biology, Kraternaya Bight has been created a preserve. INTRODUCTION From the results of these studies, from data on land volcanic discharge (see for example Zavarzin et al. Volcanic activity may have been a crucial factor in 1967), and taking into account the similarity of the the origin of life on Earth. Recent investigations have chemical composition of deep-sea hydrothermal waters shown that volcanic activity now plays a significant role and waters of land volcanic discharges, we suggested not only in formation of minerals and rocks but also in that specific communities of marine organisms may production of organic matter. -

In Crater Lake, OR

Studies ofIi HydrothermaljThcitk iNi ProcessesVL in Crater Lake, OR Robert W. Collier, Jack Dymond and James McManus College of Oceanography Oregon State University Corvallis, OR 97331 In Collaboration With: H. Phinney, D. Mclntire, G. Larson, M. Buktenica Oregon State University R. Bacon, C.'.. H. Nelson, J. H.,. Barber, Jr.ii, U.S.G.S., Menlo Park D KarlTh[ U. Hawaii J. Lupton U.C. Santa Barbara M.'i:i Watwood, C. Dahm U. of New Mexico A. Soutar, R. Weiss U. C. San Diego C. G. Wheat U. of Hawaii Submitted to: TheT National'V' Park Service, PNW Region Seattle, WA May 31, 1991 Cooperative Agreement No. CA 9000-3-0003 Subagreement No. 7 CPSU. College of Forestry, OSUji PATTULLO STUDY COLLEGE OF OCEANIC AND ATMOSPHERIC SCIENCES OSU College of Oceanography Repott # 90- 7 Studies of Hydrothermal Processes in Crater Lake, OR Robert W. Collier, Jack Dymond and James McManus College of Oceanography Oregon State University Corvallis, OR 97331 In Collaboration With: H. Phinney, D. Mclntire, G. Larson, M. Buktenica Oregon State University R. Bacon, C. H. Nelson, J. H. Barber, Jr. U.S.G.S., Menlo Park Karl U. Hawaii J. Lupton U.C. Santa Barbara M. Watwood, C. Dahm U. of New Mexico A. Soutar, R. Weiss U. C. San Diego C. G. Wheat U. of Hawaii Submitted to: The National Park Service, PNW Region Seattle, WA May 31, 1991 Cooperative Agreement No. CA 9000-3-0003 Subagreement No. 7 CPSU, College of Forestry, OSU OSU College of Oceanography Report #90-7 Executive summary Significant Observations Measurements of temperature and salt content within the South Basin of Crater Lake show surprising variations over distances of a few meters.