Mini-Assessment Report March 2016

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

14 3W Edu 080217 A4.Pdf (English)

Ethiopia: 3W - Education Cluster Ongoing Activities map (August 2017) ERITREA 5 Total Number of Partners MoE ☄ UNICEF WFP Saesie Tsaedaemba MoE MoE Dalul Red Sea WFP Kelete WFP Awelallo MoE MoE UNICEF Tselemti TIGRAY Berahile MoE UNICEF Afdera Tanqua MoE UNICEF Abergele WFP MoE UNICEF Erebti MoE WFP MoE UNICEF WFP MoE Janamora UNICEF Gulf of UNICEF WFP MoE MoE MoE Bidu Aden Sahla Teru MoE UNICEF WFP UNICEF Kurri UNICEF East MoE WFP SUDAN Sekota UNICEF Belesa UNICEF MoE West UNICEF Raya Yalo WFP Belesa MoE Dehana MoE Azebo MoE WFP UNICEF WFP Awra MoE UNICEF Gaz UNICEF MoE MoE MoE Gibla WFP Elidar Ebenat Kobo MoE AFAR MoE AMHARA MoE Meket Ewa Chifra WFP UNICEF Aysaita Simada UNICEF Dawunt WFP UNICEF UNICEF UNICEF MoE WFP UNICEF MoE DJIBOUTI UNICEF Bati WFP WFP Sayint MoE Telalak MoE MoE Argoba MoE UNICEF WFP Enbise UNICEF Ayisha Shinile BoE Sar Midir WFP UNICEF BENISHANGUL MoE WFP Gewane BoE Erer GUMU WFP Bure MoE Mudaytu UNICEF Afdem WFP UNICEF WFP BoE WFP WFP Simurobi BoE BoE Gele'alo UNICEF WFP Dembel Aw-bare UNICEF BoE Dulecha WFP DIRE Chinaksen Argoba Amibara BoE MoE Special Miesso DAWA UNICEF WFP UNICEF WFP WFP WFP MoE WFP Hareshen MoE HARERI BoE BoE MoE WFP WFP WFP Babile BoE MoE MoE MoE BoE Kebribeyah BoE SOMALIA SOUTH SUDAN Malka UNICEF WFP Anchar Balo MoE MoE BoE Aware UNICEF Midega Boke Golo Oda Oxfam Tola WFP Oxfam UNICEF WFP UNICEF WFP MoE MoE Meyumuluka MoE WFP Fik MoE UNICEF WFP BoE Hawi Degehamedo BoE WFP WFP WFP Gudina Lege WFP SOMALI Lagahida BoE Gashamo WFP WFP Hida BoE Degehabur MoE MoE MoE BoE Danot MoE Meyu Hamero -

Oromia Region Administrative Map(As of 27 March 2013)

ETHIOPIA: Oromia Region Administrative Map (as of 27 March 2013) Amhara Gundo Meskel ! Amuru Dera Kelo ! Agemsa BENISHANGUL ! Jangir Ibantu ! ! Filikilik Hidabu GUMUZ Kiremu ! ! Wara AMHARA Haro ! Obera Jarte Gosha Dire ! ! Abote ! Tsiyon Jars!o ! Ejere Limu Ayana ! Kiremu Alibo ! Jardega Hose Tulu Miki Haro ! ! Kokofe Ababo Mana Mendi ! Gebre ! Gida ! Guracha ! ! Degem AFAR ! Gelila SomHbo oro Abay ! ! Sibu Kiltu Kewo Kere ! Biriti Degem DIRE DAWA Ayana ! ! Fiche Benguwa Chomen Dobi Abuna Ali ! K! ara ! Kuyu Debre Tsige ! Toba Guduru Dedu ! Doro ! ! Achane G/Be!ret Minare Debre ! Mendida Shambu Daleti ! Libanos Weberi Abe Chulute! Jemo ! Abichuna Kombolcha West Limu Hor!o ! Meta Yaya Gota Dongoro Kombolcha Ginde Kachisi Lefo ! Muke Turi Melka Chinaksen ! Gne'a ! N!ejo Fincha!-a Kembolcha R!obi ! Adda Gulele Rafu Jarso ! ! ! Wuchale ! Nopa ! Beret Mekoda Muger ! ! Wellega Nejo ! Goro Kulubi ! ! Funyan Debeka Boji Shikute Berga Jida ! Kombolcha Kober Guto Guduru ! !Duber Water Kersa Haro Jarso ! ! Debra ! ! Bira Gudetu ! Bila Seyo Chobi Kembibit Gutu Che!lenko ! ! Welenkombi Gorfo ! ! Begi Jarso Dirmeji Gida Bila Jimma ! Ketket Mulo ! Kersa Maya Bila Gola ! ! ! Sheno ! Kobo Alem Kondole ! ! Bicho ! Deder Gursum Muklemi Hena Sibu ! Chancho Wenoda ! Mieso Doba Kurfa Maya Beg!i Deboko ! Rare Mida ! Goja Shino Inchini Sululta Aleltu Babile Jimma Mulo ! Meta Guliso Golo Sire Hunde! Deder Chele ! Tobi Lalo ! Mekenejo Bitile ! Kegn Aleltu ! Tulo ! Harawacha ! ! ! ! Rob G! obu Genete ! Ifata Jeldu Lafto Girawa ! Gawo Inango ! Sendafa Mieso Hirna -

Assessment of the Role of Agricultural Cooperatives in Input Output Market in Boke, Anchar and Darolebu Districts of West Hararghe Zone, Oromia Region, Ethiopia

Journal of Natural Sciences Research www.iiste.org ISSN 2224-3186 (Paper) ISSN 2225-0921 (Online) Vol.10, No.11, 2020 Assessment of the Role of Agricultural Cooperatives in Input Output Market in Boke, Anchar and Darolebu Districts of West Hararghe Zone, Oromia Region, Ethiopia *Birhanu Angasu Tadesse Melka Gosa Alemu Jima Degaga Oromia Agricultural Research Institute, Mechara Agricultural Research Center, P.O.BOX 19, Mechara, Ethiopia Abstract The study was conducted in three districts where agricultural cooperatives have been well promoted in West Hararghe zone to identify role of primary agricultural Cooperatives and factors affecting its role in the study area. Structured interview schedule were used to collect data from 180 cooperative members and non-members selected randomly from six agricultural cooperatives and its surrounding. Focus group discussions were also conducted to collect qualitative data from respondents. In this study, the statistical tools like descriptive statistics such as mean, frequency distribution and percentage, SWOT analysis and an index score was used to rank major constraints. Out of interviewed respondents, 66.7% were member of cooperative while 33.3% were non-members of the cooperatives. Most primary cooperative mainly focuses on the activities like provision of fertilizer (DAP, UREA and NPS), consumable food items (sugar and cooking oil) and rarely involved in improved seed distributions. Lack market interest, climate change, lack of market information, insufficient capital and low price of the marketable commodity were major constraints found in agricultural commodities in study area. Strengthening training, improve their capital, services and transparency, increasing members participation, sharing dividend to the members and annual auditing their status were major recommendation delivered for responsible bodies by the study. -

ETHIOPIA Food Security Outlook January to June 2011

ETHIOPIA Food Security Outlook January to June 2011 Following the meher harvest, which began in October Figure 1. Current estimated food security outcomes, 2010, food security has generally improved in the January 2011 meher producing parts of the country. However, due to crop damage caused by widespread floods and other weather related shocks the meher harvest is likely to be lower than initially anticipated. The Humanitarian Requirement Documents outlining assistance needs is expected to be released in February 2011. Although the National Meteorology Agency has not provided a forecast for the April to June gu/genna/belg rains, below normal performance of these rains is considered likely. This is expected to exacerbate prevailing food insecurity which resulted from near complete failure of October to December rains in southern pastoral and agro pastoral areas. Due to close to normal sapie (December/January) 2010 rains food security among the dominant root crop, For more information on FEWS NET’s Food Insecurity Severity Scale, please see: www.fews.net/FoodInsecurityScale mainly sweet potatoes growing areas in central and eastern SNNPR is estimated to remain stable Source: FEWS NET and WFP throughout the outlook period. The poor and very poor households normally rely on these harvests, during the March to May lean season. Staple food prices are likely to follow typical seasonal trends throughout the outlook period, though remain higher than the 2005 to 2009 averages given the current harvest and the continued price stabilization measures taken by the government. Seasonal calendar and critical events Source: FEWS NET FEWS NET Washington FEWS NET Ethiopia FEWS NET is a USAID-funded activity. -

1-10 Prevalence of Bovine Mastitis, Risk Factors

East African Journal of Veterinary and Animal Sciences (2018) Volume 2 (1): 1-10 Prevalence of Bovine Mastitis, Risk Factors and major Causative Agents in West Hararghe Zone, East Ethiopia Ketema Boggale, Bekele Birru*, Kifle Nigusu, and Shimalis Asras Hirna Regional Veterinary Laboratory, P.O. Box 36, Oromia Regional State, Ethiopia Abstract: A cross-sectional study was conducted from October 2009 to March 2010 in Boke, Darolebu, Kuni, Mieso and Tulo districts to estimate the prevalence of bovine mastitis, identify associated risk factors and isolate the predominant bacterial agents. A total of 1019 lactating cows were examined clinically and using California Mastitis Test (CMT) for subclinical mastitis. Standard bacteriological techniques were employed to isolate the bacterial agents. A total of 393 (38.6%) cows were positive for both clinical and subclinical mastitis. Among the risk factors, age, parity, and lactation stages were not significantly (p>0.05) associated with prevalence of mastitis. However, hygienic status of animals was associated with the occurrence of mastitis (p<0.05). Both contagious and environmental bacteria were isolated from milk samples collected from mastitic cows. The predominant bacteria isolate was Staphylococcus aureus with proportion of 14.1% followed by S. agalactiae with isolation proportion of 13.2%. E. coli and S. intermedius were the third predominant isolates with a rate of 10.9% for each. Among the seven antibiotics tested, gentamycin, amoxicillin, oxytetracycline, ampicillin, and cloxacillin were effective, whereas streptomycin and penicillin showed poor efficacy. The study revealed that mastitis is significant problem of dairy cows in the study areas. Hence, awareness creation among dairy farmers should be made about the impact of the disease; and training on hygienic milking practice and treating of subclinically infected cows should be given. -

Participatory Demonstration and Evaluation of Drought Tolerant Maize

International Scholars Journals International Journal of Agricultural Extension and Rural Development Vol. 8 (9), pp. 001-013, September, 2020. Available online at www.internationalscholarsjournals.org © International Scholars Journals Author(s) retain the copyright of this article. Full Length Research Paper Participatory demonstration and evaluation of drought tolerant maize technologies in Daro Lebu, Hawi Gudina and Boke Districts of West Hararghe Zone, Oromia National Regional State, Ethiopia 1Asfaw ZZ*, 2Mideksa BF and 2Fekede GT 1Oda Bultum University, College of Agriculture, P.O.BOX 226, Chiro, Ethiopia. 2Oromia Agricultural Research Institute, Mechara Agricultural Research Center, P.O.BOX 19 Mechara, Ethiopia. Accepted 24 August, 2020 Abstract Limited access to improved maize seed, late delivery of the available inputs, drought, insects-pests, lack of agronomics management and diseases are the major challenges facing maize production in Ethiopia. The experiment was conducted with the objective to demonstrate and evaluate the drought-tolerant maize varieties under farmers’ conditions. One kebele from each district, seven farmers, and two farmer Training Centers were used for demonstration and evaluation of maize varieties. Yield, farmers’ preference, number of participants in training and field day, cost of inputs, and benefits gained were major types of data collected using group discussion, observation, and counting. The collected data were analyzed using descriptive and inferential statistics, direct matrix and Garret ranking techniques, and partial budget analysis. The field day, training, advisory services, and supervision were conducted for the farmers with the integration of development agents and experts. MH-140 maize variety was high yielder, preferred by the farmers, and economically profitable than over MH-130 and local check varieties in the study area. -

Ethiopia Humanitarian Fund 2016 Annual Report

2016 Annual Report Ethiopia Humanitarian Fund Ethiopia Humanitarian Fund 2016 Annual Report TABLE of CONTENTS Forward by the Humanitarian Coordinator 04 Dashboard – Visual Overview 05 Humanitarian Context 06 Allocation Overview 07 Fund Performance 09 Donor Contributions 12 Annexes: Summary of results by Cluster Map of allocations Ethiopia Humanitarian Fund projects funded in 2016 Acronyms Useful Links 1 REFERENCE MAP N i l e SAUDI ARABIA R e d ERITREA S e a YEMEN TIGRAY SUDAN Mekele e z e k e T Lake Tana AFAR DJIBOUTI Bahir Dar Gulf of Aden Asayita AMHARA BENESHANGUL Abay GUMU Asosa Dire Dawa Addis Ababa Awash Hareri Ji Jiga Gambela Nazret (Adama) GAMBELA A EETHIOPIAT H I O P I A k o b o OROMIA Awasa Omo SOMALI SOUTH S SNNPR heb SUDAN ele le Gena Ilemi Triangle SOMALIA UGANDA KENYA INDIAN OCEAN 100 km National capital Regional capital The boundaries and names shown and the designations International boundary used on this map do not imply official endorsement or Region boundary acceptance by the United Nations. Final boundary River between the Republic of Sudan and the Republic of Lake South Sudan has not yet been determined. 2 I FOREWORD DASHBOARD 3 FOREWORD FOREWORD BY THE HUMANITARIAN COORDINATOR In 2016, Ethiopia continued to battle the 2015/2016 El Niño-induced drought; the worst drought to hit the country in fifty years. More than 10.2 million people required relief food assistance at the peak of the drought in April. To meet people’s needs, the Government of Ethiopia and humanitar- ian partners issued an initial appeal for 2016 of US$1.4 billion, which increased to $1.6 billion in August. -

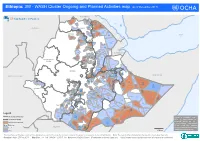

3W - WASH Cluster Ongoing and Planned Activities Map (As of December 2017)

Ethiopia: 3W - WASH Cluster Ongoing and Planned Activities map (as of December 2017) ERITREA RWB 37Total Number of Partners Ahferom ☉ Gulomekeda IRC RWB Saesie Tahtay RWB Tahtay Tsaedaemba Adiyabo JSI Koraro Dalul SCI ADCS Red Sea RWB Concern RWB VSF-Germany COOPI RWB Koneba RWB VSF-Germany SUDAN Concern TIGRAY Kelete Berahile Tselemti Awelallo Afdera Plan Concern SCI VSF-Germany RWB COOPI Bidu RWB SCI Abergele Hintalo Megale SCI AMHARA Wejirat Gulf of RWB GAA ACF RWB Erebti RWB RWB Aden Wegera ACF RWB Ziquala ACF RWB Plan JSI RWB Alamata Elidar Dehana ACF JSI RWB Gulina RWB Plan Concern Kobo AFAR Lay Guba Plan Gayint RWB Dubti RWB Lafto RWB RWB Plan Concern Habru RWB Simada Delanta LVIA CARE Adaa'r CARE Concern LVIA Mile DJIBOUTI Concern JSI Telalak RWB Kalu RWB Legambo RWB Enbise RWB RWB LVIA CARE RWB RWB Sar Midir Kelela Were Ilu Dewa Dewe Enarj Gewane Cheffa BENISHANGUL Enawga RWB Jama Bure RWB IMC GUMUZ Mudaytu Menz Gera Erer RWB RWB Midir Jille CARE IRE LVIA Shinile Timuga Afdem RWB RWB RWB Amibara IRE Oxfam Ensaro Ankober CARE Miesso RWB IMC Aw-bare RWB Kombolcha RWB RWB EOC-DICAC RWB IMC OROMIA CARE CARE RWB Oxfam Awash Mieso Deder RWB CARE DRC RWB Gursum RWB Fentale RWB Gursum NRC RWB RWB Tulo LWF CARE Mesela Oxfam Berehet Girawa IMC RWB ACF RWB Hareshen JSI ACF ACF RWB Minjar Fentale RWB SOMALIA RWB ECC-SADCO SOUTH SUDAN RWB Shenkora RWB RWB Bedeno RWB RWB CARE EOC-DICAC Gemechis WVI ChildFund Meyu RWB Midega Boset Merti Babile RWB Tola IRC RWB IRC Boke Golo Oda Gashamo RWB RWB IMC RWB Oxfam ChildFund RWB IRC RWB ADRA RWB RWB -

JAERD Opportunities and Constraints of Coffee Production in West

JAERD Journal of Agricultural Economics and Rural Development Vol. 2(4), pp. 054-059, November, 2015. © www.premierpublishers.org, ISSN: XXXX-XXXX Research Article Opportunities and constraints of coffee production in West Hararghe, Ethiopia Fekede Gemechu Tolera1* and Gosa Alemu Gebermedin2 1*,2 Oromia Agricultural Research Institute (OARI), Mechara Agricultural Research Center P.O. Box 19 Mechara, Ethiopia. Assessing factors influencing coffee production and productivity was used to develop appropriate technology for improvement and inform policy makers to understand gap concerning the commodity. Therefore, this study was designed to assess constraints and opportunities of coffee production in West Hararghe Zone. It employed multi-stage sampling procedure. In the first stage, Daro Lebu, Habro and Boke districts were selected purposively based on coffee production potential from the zone. In the second stage, a total of seven kebeles and 170 households were randomly selected. Household questionnaires were employed to collect primary data and analyzed by using descriptive statistics. The study revealed diseases, pest, poor access to market information, lack of physical infrastructure, lack of improved coffee variety and weak extensions services were major constraints of coffee production and productivity. On the other hand, high quality of Harar coffee, high demand of Hararghe coffee on world market, construction of rural road, availability of mobile phone, good indigenous knowledge were major opportunities for coffee producers in the area. Therefore, findings of study indicated that development of disease resistance coffee variety, assessment of farmers` indigenous knowledge, providing extension service and enhancing infrastructural and institution facilities need emphasis to improve coffee production and productivity. Key words: Coffee landrace, farmers` indigenous knowledge, coffee disease, market access. -

Horn of Africa

! S A U D I A R A B I A THUMRAIT BARBAR MAKKAH NORTHERN EASTERN MERAWI ASIR PROVINCE AD DAMER TOKAR SINKAT JIZAN NAJRAN ATBARA RED SEA Horn of Africa ! ADOBHE QUARURA AL MATAMMAH NILE SEMENAWI S,ADAH General Location Map KEIH BAHRI ! HAMASHKORIEB ! ! ! SHENDI SEL'A ! NAKFA ! ! KARARY ANSEBA ! AL JAWF HADRAMAUT AL GASH ! ASMAT HABERO KERKEBET AFABET KHARTOUM HALHAL Red AL MAHARAH UM DURMAN KHARTOUM SHARG BAHRI FORTO DAHLAK EN NILE BUTANA KASSALA AMRAN ! NAHR Sea HAJJAH KHARTOUM ! ATBARA ERITRE A SHEB KASSALA DGE ADI TEKELIEZAN ! ! ! Y E M E N JABAL AKURDET HAGAZ UM BADDA GASH AULIA MENSURA SEREJEQA ! LOGO TESSENEY BARKA ! HAIKOTA SOUTHERN AL KAMLIN MOGOLO ANSEBA ASMARA GINDAE MARIB ! NORTH AL ! AL HUDAYDAH ! ! ! ! AL HASAHEISA GONEI FORO JAZEERA ! DBARWA AL MAHWIT ! AL FAW BARENTU MOLQI SANA'A AL GUTAINA AL JAZEERA DEKEMHARE ! SHAMBQO ! LA'ELAY MAI AINI ! GASH ADI KEIH GEL'ALO SHABWAH AREZA ADI ! ! AL MAI MNE ! KUALA SENAFE DHAMAR MANAGIL ! ! ! SOUTH AL UM AL GURA OMHAJER EASETERN DEBUBAWI S U D A N SETEET TIGRAY CENTRAL JAZEERA ! TIGRAY KEIH BAHRI AL ! AL ARA'ETA ! ! KAFTA DALUL EAST AL AL FUSHQA HUMERA NORTH BAYDA WESTERN ! JAZEERA GADAREF TIGRAY TIGRAY ! ! IBB AD AD DOUIEM ! ! ! GADAREF DALI ! ! BERAHLE CENTRAL ABYAN SENNAR ! AL RAHD TSEGEDE MEKELE AFAR SRS ! AL GALABAT ZONE 2 SOUTHERN MIRAB SOUTHERN AFDERA TAIZZ TIGRAY AB ALA SRS KOSTI ARMACHO TACH EREBTI SENNAR ARMACHO -

ETHIOPIA East and West Hararge Access Snapshot As of 14 June 2019

ETHIOPIA East and West Hararge Access Snapshot As of 14 June 2019 Historical resource-based conflicts - Despite this general improvement of the security situation, over water and grazing land - have been humanitarianORIGIN partners OF do notIDPS have yet access to some areas Siti Dire Dawa mostly due to a combination of security and road conditions prevalent between communities across Somali SOMALI Jarso (East Hararghe)Chinaksen SOMALI SOMALI DIRE DAWA Chinaksen Number of IDPs displaced within boundary areas between Oromia and Zone 3Addis (Gabi Ababa Rasu) Jarso Chinaksen factors. Amhara 11% DIRE DAWA JarsoKombolcha 174,726 the same woreda in East Hararge Somali regions. Localized skirmishes in AFAR Siti Meta Kombolcha AFAR Goro Gutu MetaKersa (EastKombolcha Hararge) (127,909, 55%) and West Hararge Afar Siti Goro Gutu Kersa Harari Gursum (Oromia) In East Hararge, five kebeles in Kumbi woreda and three in 2015 displaced thousands of agro-pas- Goro Gutu Meta Haro Maya ChinaksenGursum (60%) Doba Deder Town KersaDIRE DAWAHaro Maya Aweday Town (46,817, 82%). toralists. This continued in 2017, and in Doba Deder Town Haro MayaAweday JarsoTown HARARI Meyu Muluke have been occupied by the Somali Liyu Police Doba Deder Town HarariGursum AwedayKurfa TownKombolcha Chele Babile Town HARARI since 2015, impending the return of over 80,000 IDPs. In Mieso DederDederGoro Muti Kurfa Chele August - September, conflict escalated along the entire MiesoMieso GoroKurfa Muti Chele BabileGursum BabileTown (Oromia) Most of the IDPs displaced in East and West Hararge AFAR TuloTulo (Oromia) (Oromia)GoroDeder GutuGoro MutiMeta Babile Fafan addition, the situation in two kebeles in Meyu Muluke regional boundary resulting in massive displacements. -

A Joint Mission Report to Gumbi Bordode and Miesso Woreda of West Hararghe Zone Date:3-4 June 2020 Participants: Plan International, CARE and OCHA

A joint mission report to Gumbi Bordode and Miesso woreda of West Hararghe zone Date:3-4 June 2020 Participants: Plan International, CARE and OCHA 5 June 2020 Executive Summary The IDPs in Burka Anani kebele of Gumbi Bordode woreda were displaced from their original place Ta’a Gumbi kebele across the border with Afar region in February 2020. The IDPs counted over three months in this new place. A total of 740HHs(3700 people) were displaced and dispersed in three locations: Burka Anani(240HHs),Sama(255HHs) and Aragessa(245HHs).The IDPs in Burka Anani site is the one visited by the team. According to our observation, these IDPs can be considered as neglected population with critical and huge humanitarian needs among which food and water were put on the top. The IDPs reported not receiving food for the last 3 months except the one-month half ration they received from Badessa town community as a part of people to people support. Access to water is very challenging. In addition to the need for long travel of over 10 Kms, security remains a major concern hindering/frightening women not to travel alone to fetch water.Reportedly,some armed men has to travel to the river early in the morning(starting from 6am) to patrol the area before the women and children go to fetch the water . The women and children will follow the men starting from 7am and the families who remain at home remain worried until all return around noon. The IDPs are not getting basic health services. No health post in their current location and outreach services from HEWs based in Gololcha has been compromised due to the security.