Pollination Structures Plant and Nectar‐Feeding Bird

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

South Africa Cape Wildflowers, Birding & Big Game II 21St August to 3Rd September 2022 (14 Days)

South Africa Cape Wildflowers, Birding & Big Game II 21st August to 3rd September 2022 (14 days) Cape Mountain Zebras & wildflowers in West Coast NP by Adam Riley This comprehensive tour covers the most exciting regions of the Cape in our quest to experience both breathtaking displays of wildflowers and to track down some of the country’s endemic birds. We begin in the vibrant city of Cape Town, where Table Mountain provides a spectacular backdrop to the immensely diverse fynbos that cloaks the cities periphery. This fynbos constitutes the Cape Floral Kingdom – the smallest and richest of the world’s 6 floral kingdoms. It is also the only floral kingdom to be confined to the boundaries of a single country. Thereafter we venture to the West Coast and Namaqualand, which boast an outrageous and world famous floral display in years of good rains, before travelling through the heart of the country’s semi-desert region, focusing on the special bird’s endemic to this ancient landscape. We conclude the journey heading out of wildflower country to Augrabies Falls, an area offering unparalleled raptor viewing and a wide range of dry region birds. We invite you on this celebration of some of the finest wildflower and endemic birding that the African continent has to offer! RBT South Africa - Cape Wildflowers, Birding & Big Game 2 THE TOUR AT A GLANCE… THE ITINERARY Day 1 Arrival in Upington Day 2 Upington to Augrabies Falls National Park Day 3 Augrabies Falls National Park Day 4 Augrabies Falls National Park to Springbok Day 5 Springbok to Nieuwoudtville -

Protea May Predict Occurrence and Abundance Alan T.K

Cape Sugarbird: Flowering Protea may predict occurrence and abundance Alan T.K. Lee 1, 2 1 Birds & Environmental Change Programme, Climate Change & BioAdaptation Division, South African National Biodiversity Institute 2 Percy FitzPatrick Institute of African Ornithology, University of Cape Town, Rondebosch 7701, South Africa [email protected] Introduction Results The Cape Sugarbird Promerops cafer (Fig. 1) is one of six 1.A total of 361 Cape Sugarbirds (249 groups) were recorded species of bird restricted to the Fynbos biome. The bird is an during 820 counts, with an overall density estimate of 17 (13-21) important pollinator of certain Protea species and the close birds/km2 association between this endemic bird and a subgroup of flowering species of the Protea genus has been known for 2.17% of points were classified as ‘proteoid’, and 55% of bird some time 1. Reliance of Cape Sugarbirds on other Fynbos encounters were recorded in this habitat type (Fig. 3) families or environmental variables less well known. 3.Cape Sugarbird abundance was strongly positively correlated Increased fire frequency and climate change may impact on with bird pollinated Protea, Protea flower scores, vegetation this species habitat 2, and some evidence suggests range height and other proteaceae; while negatively correlated with has contracted over the last 20 years 3. Loss of this key grass, rocky outcrop and plant families associated with dry species may have implications for the pollination of a wide Fynbos (Table 1) range of Protea species. We aimed to: 1.Determine the status of Cape Sugarbird across the Fynbos biome; 2. -

Image Identification of Protea Species with Attributes and Subgenus Scaling

Image identification of Protea species with attributes and subgenus scaling Peter Thompson Willie Brink Stellenbosch University Stellenbosch University [email protected] [email protected] Abstract The flowering plant genus Protea is a dominant repre- sentative for the biodiversity of the Cape Floristic Region in South Africa, and from a conservation point of view im- portant to monitor. The recent surge in popularity of crowd- sourced wildlife monitoring platforms presents both chal- lenges and opportunities for automatic image based species identification. We consider the problem of identifying the Protea species in a given image with additional (but op- tional) attributes linked to the observation, such as loca- tion and date. We collect training and test data from a crowd-sourced platform, and find that the Protea identifi- Figure 1. Different species of Protea, such as Protea neriifolia cation problem is exacerbated by considerable inter-class and Protea laurifolia shown here, can exhibit considerable visual similarity, data scarcity, class imbalance, as well as large similarity. variations in image quality, composition and background. Our proposed solution consists of three parts. The first part incorporates a variant of multi-region attention into a pre- important for understanding species populations [3] in the trained convolutional neural network, to focus on the flow- midst of issues like global warming, pollution and poach- erhead in the image. The second part performs coarser- ing. The crowd-sourced platform iNaturalist for example grained classification on subgenera (superclasses) and then allows users to upload observations of wildlife, which typ- rescales the output of the first part. The third part con- ically include images, locations, dates, and identifications ditions a probabilistic model on the additional attributes that can be verified by fellow users [31]. -

Urbanization, Climate and Ecological Stress Indicators in an Endemic Nectarivore, the Cape Sugarbird

Urbanization, climate and ecological stress indicators in an endemic nectarivore, the Cape Sugarbird B. Mackay, A. T. K. Lee, P. Barnard, A. P. Møller & M. Brown Journal of Ornithology ISSN 2193-7192 J Ornithol DOI 10.1007/s10336-017-1460-9 1 23 Your article is protected by copyright and all rights are held exclusively by Dt. Ornithologen-Gesellschaft e.V.. This e-offprint is for personal use only and shall not be self- archived in electronic repositories. If you wish to self-archive your article, please use the accepted manuscript version for posting on your own website. You may further deposit the accepted manuscript version in any repository, provided it is only made publicly available 12 months after official publication or later and provided acknowledgement is given to the original source of publication and a link is inserted to the published article on Springer's website. The link must be accompanied by the following text: "The final publication is available at link.springer.com”. 1 23 Author's personal copy J Ornithol DOI 10.1007/s10336-017-1460-9 ORIGINAL ARTICLE Urbanization, climate and ecological stress indicators in an endemic nectarivore, the Cape Sugarbird 1 1,2 1,2 3 4,5 B. Mackay • A. T. K. Lee • P. Barnard • A. P. Møller • M. Brown Received: 10 February 2016 / Revised: 6 October 2016 / Accepted: 21 April 2017 Ó Dt. Ornithologen-Gesellschaft e.V. 2017 Abstract Stress, as a temporary defense mechanism urban settlements had higher levels of fluctuating asym- against specific stimuli, can place a bird in a state in which metry and fault bars in feathers. -

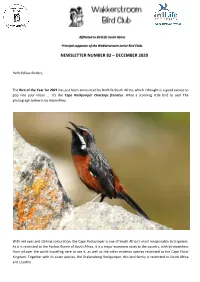

Newsletter Number 82 – December 2020

Affiliated to BirdLife South Africa Principal supporter of the Wakkerstroom Junior Bird Clubs NEWSLETTER NUMBER 82 – DECEMBER 2020 Hello fellow Birders, The Bird of the Year for 2021 has just been announced by BirdLife South Africa, which I thought is a good excuse to pop into your Inbox …. It’s the Cape Rockjumper Chaetops frenatus. What a stunning little bird to see! The photograph below is by Adam Riley. With red eyes and striking colouration, the Cape Rockjumper is one of South Africa’s most recognisable bird species. As it is restricted to the Fynbos Biome of South Africa, it is a major economic asset to the country, with birdwatchers from all over the world travelling here to see it, as well as the other endemic species restricted to the Cape Floral Kingdom. Together with its sister species, the Drakensberg Rockjumper, this bird family is restricted to South Africa and Lesotho. BirdLife South Africa chose this species as ‘Bird of the Year’ as it is an ambassador for the Fynbos biome: the unique plant kingdom found only in South Africa. There are seven other bird species found here and nowhere else on earth: Cape Sugarbird, Orange-breasted Sunbird, Protea Canary, Cape Siskin, Victorin’s Warbler, Agulhas Long-billed Lark and Hottentot Buttonquail. The Fynbos extends from the northern Cederberg through the Cape Fold Mountains, to Port Elizabeth, with fragments as far as Makhanda/Grahamstown. The Fynbos is generally well protected within the Cape Nature reserves of the Western Cape, but there are major concerns regarding the spread of alien tree species like pines and wattles, as well as increased fire frequencies as a result of climate change. -

NEST-SITE SELECTION in the CAPE SUGARBIRD We Dedicate

NEST-SITE SELECTION IN THE CAPE SUGARBIRD A. E. BURGER, W. R. SlEGFRIED & P. G. H. FROST Percy FitzPatrick Institute, University of Cape Town We dedicate this paper to the memory of the late Dr G. J. Broekhuysen, our former mentor and friend, who did more than any other person in laying the foundations for an eco-ethologica1 approach in scientific studies ofthe avifauna of the south-western Cape region ofSouth Mrica. ABSTRACT Cape sugarbirds, P,ome,ops cafe" preferred certain protea bushes as nest-sites. These bushes were characterized by relatively large leaves and dense foliage. Nests were usually placed in the central parts of bushes Nest-sites were shielded from the cold night sky, and were associated with relatively favourable air temperatures and protection from wind in a season of unfavourable weather. Data on microclimate of nest-sites, together with those on heat loss from an incubating sugarbird, were interpreted in relation to nest-site selection as adaptive behaviour promoting breeding success through conservation of energy. Sugarbirds nesting relatively high off the ground and in dense vegetation were considered to be decreasing the risk of exposure to predators. ) 0 1 0 2 d INTRODUCTION e t a d ( r Food availability, and shelter from predators and adverse weather are ultimate factors in habitat e h s selection in bird species (Baker 1938; Hilden 1965). Nest-site selection is not a random procedure, i l b and nest building will commence only when the summation of the heterogeneous stimuli of the u P micro-habitat exceeds the threshold for releasing nesting behaviour. -

The Functional Role of Birds As Pollinators in Southern Cape Fynbos

The functional role of birds as pollinators in southern Cape fynbos. Kellyn J. Whitehead A thesis presented in fulfilment of the academic requirements for the degree of Masters of Science in Ecological Sciences At the University of KwaZulu-Natal, Pietermaritzburg, South Africa January 2018 1 ABSTRACT Nectarivorous birds, particularly sunbirds, are important pollinators of plants in the Cape Flora of South Africa, being responsible for pollinating approximately 5% of plant species. However, interactions between plants and nectarivorous birds in the eastern part of the Cape Floristic Region have not received much attention. This study focussed on two putatively bird-pollinated plant species found within the Nature’s Valley area, namely Kniphofia uvaria and Chasmanthe aethiopica. The breeding systems were determined for each species and, due to their patchy population distribution, potential Allee effects on plant fecundity were also tested for. Flowering phenology in the area was also examined to test for associations between flowering of bird-pollinated plant species and the temporal presence of nectarivorous birds. Selective exclusion experiments showed that sunbirds were the main pollinators of K. uvaria and C. aethiopica – fruit set and the number of viable seeds were much higher for untreated (open control) individuals where birds could visit flowers freely, compared to caged individuals which only allowed for insect visitation. Very few seeds developed when plants of the two species were bagged to exclude all pollinators, indicating that the species are not capable of autonomous self-fertilization. Fruit and seed set were determined for patches of K. uvaria and C. aethiopica in order to test for potential Allee effects. -

Reproductive Biology of Three Co-Occurring, Primarily Small-Mammal Pollinated Protea Species (Proteaceae)

South African Journal of Botany 113 (2017) 337–345 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect South African Journal of Botany journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/sajb Reproductive biology of three co-occurring, primarily small-mammal pollinated Protea species (Proteaceae) N. Kühn a,b,⁎,J.Midgleya, S.-L. Steenhuisen a,c a Department of Biological Sciences, University of Cape Town, P/Bag X3, Rondebosch, 7701, South Africa b Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, Richmond, Surrey TW9 3DS, UK c Department of Plant Sciences, Natural and Agricultural Sciences Building, Qwaqwa Campus, University of the Free State, 9866, South Africa article info abstract Article history: This study investigated the role of vertebrates in the reproductive biology of a community of three co-occurring Received 13 January 2017 Protea species (Protea canaliculata, Protea sulphurea and Protea humiflora, Proteaceae) at Kraggashoek in the Received in revised form 10 August 2017 Western Cape, South Africa. Live-trapping, measures of facial and faecal pollen loads, and footage from remote Accepted 29 August 2017 cameras facing the inflorescences confirmed that all three are visited by small mammals and specialist nectarivorous birds. These plant species have bowl-shaped inflorescences that produce highly concentrated Edited by Glynis Goodman/Cron (34.1–42.9%) sucrose-rich nectar and a “yeasty” scent, typical traits of small-mammal pollinated plants. Camera fl Keywords: footage indicated that 140 visits were made by eight small mammal species to an accumulative 19 in orescences Small mammal pollination of the three Protea species. Small mammals thus made up 69% of total visits by all vertebrate species. Camera Specialist sunbird pollinators footage revealed that Micaelamys namaquensis visited flowers more frequently than any other vertebrate visitor Protea (41% of total visitations by birds and mammals) but Elephantulus edwardii (10% of total visitations by birds and Proteaceae mammals) spent the longest time foraging on inflorescences (~28 s per inflorescence). -

Critical Resources and Habitats of the Endemic Fynbos Bird Community

Postdoctoral research proposal Climate Change Impacts on Fynbos Endemic Birds: Spatial and temporal patterns of abundance and dispersal of Fynbos avifauna Dr. Alan T. K. Lee Blue Hill Escape, P.O. Box 131, Uniondale, Western Cape, South Africa, 6460 044 752 1254 [email protected] Rationale Bird communities in the Fynbos biome face documented threats from alien vegetation encroachment, changes in burning regimes, and human modification of the landscape. The status of bird populations under current conditions has not been recently quantified, and while modelling assessments have determined that Fynbos bird species under vulnerable under various climate change scenarios no study has used real abundance data. There are six bird species recognised as globally restricted to the Fynbos. These are currently listed by IUCN conservation criteria as species of Least Concern, despite a lack of information on population size and little evaluation of population trends and range size changes. Recent reviews of their distribution, together with the impacts of climate change, suggest that their conservation criteria need to be re-examined. However, quantitative information on movements, densities and population sizes is lacking for most bird species that inhabit mountain Fynbos. This study aims to establish baseline density data for bird communities in the Mountain Fynbos habitat element; determine patterns of dispersal and abundance along aridity and altitudinal gradients to predict vulnerability of populations to future climate change; and determine how well these predictions could have been achieved using Southern African Bird Atlas Project data. Introduction Most of the Fynbos biome of the south-western and southern South Africa is included within the Cape Fynbos Endemic Bird Area (EBA), which extends from the Cederberg Mountains south and eastwards to Algoa Bay (BirdLife International 2010). -

Mite (Acari) Ecology Within Protea Communities in The

MITE (ACARI) ECOLOGY WITHIN PROTEA COMMUNITIES IN THE CAPE FLORISTIC REGION, SOUTH AFRICA NATALIE THERON-DE BRUIN Dissertation presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Faculty of Agrisciences at Stellenbosch University Promoter: Doctor F. Roets, Co-promoter: Professor L.L. Dreyer March 2018 Stellenbosch University https://scholar.sun.ac.za DECLARATION By submitting this dissertation electronically, I declare that the entirety of the work contained therein is my own, original work, that I am the sole author hereof (save to the extent explicitly otherwise stated), that reproduction and publication therefore by the Stellenbosch University will not infringe any third party rights and that I have not previously in its entirety or in part submitted it for obtaining any qualification. ..................................... Natalie Theron-de Bruin March 2018 Copyright © 2018 Stellenbosch University All rights reserved i Stellenbosch University https://scholar.sun.ac.za GENERAL ABSTRACT Protea is a key component in the Fynbos Biome of the globally recognised Cape Floristic Region biodiversity hotspot, not only because of its own diversity, but also for its role in the maintenance of numerous other organisms such as birds, insects, fungi and mites. Protea is also internationally widely cultivated for its very showy inflorescences and, therefore, has great monetary value. Some of the organisms associated with these plants are destructive, leading to reduced horticultural and floricultural value. However, they are also involved in intricate associations with Protea species in natural ecosystems, which we still understand very poorly. Mites, for example, have an international reputation to negatively impact crops, but some taxa may be good indicators of sound management practices within cultivated systems. -

Biodiversity Fact Sheets: Threatened Species

Biodiversity Fact Sheets: Threatened Species * Supplementary document to a series of 8 biodiversity fact sheets* RED LIST PLANTS Critically Endangered (CR) Afrolimon purpuratum CR Aristea ericifolia erecta CR Arctotheca forbesiana CR Aspalathus aculeata CR Aspalathus horizontalis CR Aspalathus rycroftii CR Babiana leipoldtii CR Babiana regia CR Babiana secunda CR Cadiscus aquaticus CR Cephalophyllum parviflorum CR Chrysocoma esterhuyseniae CR Cliffortia acockii CR Cotula myriophylloides CR Cyclopia latifolia CR Diastella proteoides CR Disa barbata CR Disa nubigena CR Disa physodes CR Disa sabulosa CR Erica abietina diabolis CR Erica bolusiae bolusiae CR Erica heleogena CR Erica malmesburiensis CR Erica margaritacea CR Erica ribisaria CR Erica sociorum CR Erica ustulescens CR Erica vallis‐aranearum CR Geissorhiza eurystigma CR Geissorhiza malmesburiensis CR Geissorhiza purpurascens CR Gladiolus aureus CR Gladiolus griseus CR Hermannia procumbens procumbens CR Holothrix longicornu CR Ixia versicolor CR Lachenalia arbuthnotiae CR Lachenalia purpureo ‐caerulea CR Lampranthus tenuifolius CR Leucadendron floridum CR Leucadendron lanigerum laevigatum CR Leucadendron levisanus CR Leucadendron macowanii CR Leucadendron stellare CR Leucadendron thymifolium CR Leucadendron verticillatum CR Marasmodes oligocephala CR Marasmodes polycephala CR Metalasia distans CR Mimetes hottentoticus CR Moraea angulata CR Moraea aristata CR Muraltia satureioides salteri CR Oxalis natans CR Podalyria microphylla CR Polycarena silenoides CR Protea odorata CR Psoralea -

Kirstenbosch NBG List of Plants That Provide Food for Honey Bees

Indigenous South African Plants that Provide Food for Honey Bees Honey bees feed on nectar (carbohydrates) and pollen (protein) from a wide variety of flowering plants. While the honey bee forages for nectar and pollen, it transfers pollen from one flower to another, providing the service of pollination, which allows the plant to reproduce. However, bees don’t pollinate all flowers that they visit. This list is based on observations of bees visiting flowers in Kirstenbosch National Botanical Garden, and on a variety of references, in particular the following: Plant of the Week articles on www.PlantZAfrica.com Johannsmeier, M.F. 2005. Beeplants of the South-Western Cape, Nectar and pollen sources of honeybees (revised and expanded). Plant Protection Research Institute Handbook No. 17. Agricultural Research Council, Plant Protection Research Institute, Pretoria, South Africa This list is primarily Western Cape, but does have application elsewhere. When planting, check with a local nursery for subspecies or varieties that occur locally to prevent inappropriate hybridisations with natural veld species in your vicinity. Annuals Gazania spp. Scabiosa columbaria Arctotis fastuosa Geranium drakensbergensis Scabiosa drakensbergensis Arctotis hirsuta Geranium incanum Scabiosa incisa Arctotis venusta Geranium multisectum Selago corymbosa Carpanthea pomeridiana Geranium sanguineum Selago canescens Ceratotheca triloba (& Helichrysum argyrophyllum Selago villicaulis ‘Purple Turtle’ carpenter bees) Helichrysum cymosum Senecio glastifolius Dimorphotheca