Chapter 3: Refuge Environment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ecoregions of New England Forested Land Cover, Nutrient-Poor Frigid and Cryic Soils (Mostly Spodosols), and Numerous High-Gradient Streams and Glacial Lakes

58. Northeastern Highlands The Northeastern Highlands ecoregion covers most of the northern and mountainous parts of New England as well as the Adirondacks in New York. It is a relatively sparsely populated region compared to adjacent regions, and is characterized by hills and mountains, a mostly Ecoregions of New England forested land cover, nutrient-poor frigid and cryic soils (mostly Spodosols), and numerous high-gradient streams and glacial lakes. Forest vegetation is somewhat transitional between the boreal regions to the north in Canada and the broadleaf deciduous forests to the south. Typical forest types include northern hardwoods (maple-beech-birch), northern hardwoods/spruce, and northeastern spruce-fir forests. Recreation, tourism, and forestry are primary land uses. Farm-to-forest conversion began in the 19th century and continues today. In spite of this trend, Ecoregions denote areas of general similarity in ecosystems and in the type, quality, and 5 level III ecoregions and 40 level IV ecoregions in the New England states and many Commission for Environmental Cooperation Working Group, 1997, Ecological regions of North America – toward a common perspective: Montreal, Commission for Environmental Cooperation, 71 p. alluvial valleys, glacial lake basins, and areas of limestone-derived soils are still farmed for dairy products, forage crops, apples, and potatoes. In addition to the timber industry, recreational homes and associated lodging and services sustain the forested regions economically, but quantity of environmental resources; they are designed to serve as a spatial framework for continue into ecologically similar parts of adjacent states or provinces. they also create development pressure that threatens to change the pastoral character of the region. -

Spatial Variation in Fish Assemblages Across a Beaver-Influenced Successional Landscape

Ecology, 81(5), 2000, pp. 1371±1382 q 2000 by the Ecological Society of America SPATIAL VARIATION IN FISH ASSEMBLAGES ACROSS A BEAVER-INFLUENCED SUCCESSIONAL LANDSCAPE ISAAC J. SCHLOSSER1,3 AND LARRY W. K ALLEMEYN2 1Department of Biology, Box 9019, University Station, Grand Forks, North Dakota 58202 USA 2United States Geological Survey, Columbia Environmental Research Center, International Falls Biological Station, 3131 Highway 33, International Falls, Minnesota 56649 USA Abstract. Beavers are increasingly viewed as ``ecological engineers,'' having broad effects on physical, chemical, and biological attributes of north-temperate landscapes. We examine the in¯uence of both local successional processes associated with beaver activity and regional geomorphic boundaries on spatial variation in ®sh assemblages along the Kabetogama Peninsula in Voyageurs National Park, northern Minnesota, USA. Fish abun- dance and species richness exhibited considerable variation among drainages along the peninsula. Geological barriers to ®sh dispersal at outlets of some drainages has reduced ®sh abundance and species richness. Fish abundance and species richness also varied within drainages among local environments associated with beaver pond succession. Fish abun- dance was higher in upland ponds than in lowland ponds, collapsed ponds, or streams, whereas species richness was highest in collapsed ponds and streams. Cluster analyses based on ®sh abundance at sites classi®ed according to successional environment indicated that four species (northern redbelly dace, Phoxinus eos; brook stickleback, Culaea incon- stans; ®nescale dace, P. neogaeus; and fathead minnow, Pimephales promelas), were pre- dominant in all successional environments. Several less abundant species were added in collapsed ponds and streams, with smaller size classes of large lake species (e.g., black crappie, Pomoxis nigromaculatus; smallmouth bass, Micropertus dolomieui; yellow perch, Perca ¯avescens; and burbot, Lota lota) being a component of these less abundant species. -

Carbon Stocks and Soil Sequestration Rates of Riverine Mangroves and Freshwater Wetlands” by M

Open Access Biogeosciences Discuss., 12, C614–C618, 2015 www.biogeosciences-discuss.net/12/C614/2015/ Biogeosciences © Author(s) 2015. This work is distributed under Discussions the Creative Commons Attribute 3.0 License. Interactive comment on “Carbon stocks and soil sequestration rates of riverine mangroves and freshwater wetlands” by M. F. Adame et al. Anonymous Referee #1 Received and published: 15 March 2015 General comments: In this manuscript, Adame and colleagues measured carbon pools in vegetation, downed wood, and soils of seven mangrove sites, one peat swamp for- est, and one herbaceous marsh within Mexico’s La Encrucijada Biosphere Reserve (LEBR). They also measured soil N pools at all sites and rates of soil C sequestra- tion at the mangrove sites. The peat swamp and marsh sites appear to have been included only for the sake of making casual (rather than statistical) comparisons, since there was just one of each of those site types. The primary hypothesis was that soil C and N stocks and soil C sequestration rates would be higher in upland vs. lowland mangroves. This is a very descriptive place-based study. Although the authors made some sugges- tions about why some sites store more carbon than others (e.g., perhaps it is related C614 to geomorphology or the dominant tree species), this manuscript didn’t leave me with any new ideas or insights about how wetlands “work.” I didn’t feel that it told me any- thing more than some specific information about one specific location, and I think that will limit its appeal to the diverse readership of Biogeosciences. -

Chapter 3 M-32 & Old 27 / I-75 Business Loop Corridor Study

M-32 & Old 27 / I-75 Business Loop Corridor Study Environmental Analysis The wealth of natural resources within Otsego County is important to the overall health and vigor of the community; these resources are an economic anchor and play a key role in the quality of life for county residents. The study area traverses rolling hills, forestlands, farmlands, open spaces and high quality water resources, presenting an ever changing array of scenic vistas. Natural resources within the 1/2 mile wide corridor are connected to much larger regional landscape features, and as a result, activities within the study area can have far reaching effects. The natural resources addressed in this chapter include forests, wetlands, farmlands, soils and water. A soils based analysis of development constraints will also be included in this chapter. Natural Resources Forests In addition to the scenic characteristics of woodlands, forested areas provide habitat for wildlife, protect the soil from erosion, filter air pollutants and act as a noise buffer along heavily traveled highways. Public and privately owned forested lands can be found throughout the corridor study area. Forest lands were mapped as a part of the existing land use analysis in Chapter 2. As noted in Chapter 2, woodland areas, both upland and lowland forest types, cover over 32 percent of the study area. Figure 3.1 is a map depicting the location of woodlands and wetlands within the study corridor. The dominant forest associations in the corridor study area are northern hardwoods (sugar maple, American beech and basswood); aspen/white birch; red and white oak and red pine plantations in the upland areas. -

Factors Affecting Distribution of Wood, Detritus, and Sediment in Headwater Streams Draining Managed Young-Growth Red Alder - Conifer Forests in Southeast Alaska

Factors affecting distribution of wood, detritus, and sediment in headwater streams draining managed young-growth red alder - conifer forests in southeast Alaska Takashi Gomi, Adelaide C. Johnson, Robert L. Deal, Paul E. Hennon, Ewa H. Orlikowska, and Mark S. Wipfli Abstract: Factors (riparian stand condition, management regimes, and channel properties) affecting distributions of wood, detritus (leaves and branches), and sediment were examined in headwater streams draining young-growth red alder (Alnus rubra Bong.) - conifer riparian forests (40 years old) in southeast Alaska. More riparian red alder were found along streams affected by both timber harvesting and mass movement than in streams affected by timber harvest- ing alone. Young-growth stands produced little large wood material (diameter >10 cm) and had little effect on altering the size distribution of functional large wood in channels, although more alder wood pieces were found in streams with greater numbers of riparian alder trees. Legacy wood pieces (>40 years old) remained in channels and provided sites for sediment and organic matter storage. Despite various alder-conifer mixtures and past harvesting effects, the abun- dance of large wood, fine wood, and detritus accumulations significantly decreased with increasing channel bank-full width (0.5-3.5 m) along relatively short channel distances (up to 700 m). Changes in wood, detritus, and sediment ac- cumulations together with changes in riparian stand characteristics create spatial and temporal variability of in-channel -

Shifting Mineral and Redox Controls on Carbon Cycling in Seasonally flooded Mineral Soils

Biogeosciences, 16, 2573–2589, 2019 https://doi.org/10.5194/bg-16-2573-2019 © Author(s) 2019. This work is distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License. Shifting mineral and redox controls on carbon cycling in seasonally flooded mineral soils Rachelle E. LaCroix1, Malak M. Tfaily2, Menli McCreight1, Morris E. Jones1, Lesley Spokas1, and Marco Keiluweit1 1School of Earth & Sustainability and Stockbridge School of Agriculture, University of Massachusetts, Amherst, MA, USA 2Soil, Water and Environmental Science Department, University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ, USA Correspondence: Marco Keiluweit ([email protected]) and Rachelle E. LaCroix ([email protected]) Received: 4 October 2018 – Discussion started: 12 October 2018 Revised: 5 June 2019 – Accepted: 12 June 2019 – Published: 4 July 2019 Abstract. Although wetland soils represent a relatively small land soils, yet Feo had no predictive power in lowland soils. portion of the terrestrial landscape, they account for an esti- Instead, our model showed that Eh and oxalate-extractable Al mated 20 %–30 % of the global soil carbon (C) reservoir. C (Alo, a proxy of protective Al phases) became significantly stored in wetland soils that experience seasonal flooding is stronger predictors in the lowland soils. Combined, our re- likely the most vulnerable to increased severity and duration sults suggest that low redox potentials are the primary cause of droughts in response to climate change. Redox conditions, for C accumulation in seasonally flooded surface soils, likely plant root dynamics, and the abundance of protective mineral due to selective preservation of organic compounds under phases are well-established controls on soil C persistence, anaerobic conditions. -

Long-Term Reproductive Behaviour of Woody Plants Across Seven

Ecology Letters, (2007) 10: 956–969 doi: 10.1111/j.1461-0248.2007.01089.x LETTER Long-term reproductive behaviour of woody plants across seven Bornean forest types in the Gunung Palung National Park (Indonesia): suprannual synchrony, temporal productivity and fruiting diversity Abstract Charles H. Cannon,1,2* Lisa M. For 68 months, we observed the reproductive behaviour of 7288 woody plants (172 figs, Curran,3 Andrew J. Marshall4 and 1457 climbers and 5659 trees) spanning major soil and elevational gradients. Two Mark Leighton5 2–3 month community-wide supra-annual fruiting events were synchronized across five 1 Department of Biological forest types, coinciding with ENSO events. At least 27 genera in 24 families restricted Sciences, Texas Tech University, their reproduction to these events, which involved a substantial proportion of tree Box 43131, Lubbock, TX 79409- diversity (> 80% of phylogenetic diversity). During these events, mean reproductive 3131, USA levels (8.5%) represented an almost four-fold increase compared with other months. 2Xishuangbanna Tropical These patterns indicate a strong behavioural advantage to this unusual reproductive Botanic Garden, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Kunming, behaviour. Montane forest experienced a single, separate fruiting peak while the peat Yunnan 650223, China swamp forest did not participate. Excluding these events, no temporal reproductive 3School of Forestry and pattern was detectible, at either the landscape or forest type. These phenological patterns Environmental Studies, Yale have major implications for the conservation of frugivore communities, with montane University, 205 Prospect Street, and swamp forests acting as ÔkeystoneÕ forests. New Haven, CT 06511, USA 4Department of Anthropology Keywords and Graduate Group in Ecology, Keystone forest type, liana, mast fruiting, phenology, phylogenetic diversity, tropical University of California, One trees. -

Comparative Economic Analysis of Upland and Lowland Rice Production in Izzi Local Government Area of Ebonyi State

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by International Institute for Science, Technology and Education (IISTE): E-Journals Journal of Economics and Sustainable Development www.iiste.org ISSN 2222-1700 (Paper) ISSN 2222-2855 (Online) Vol.5, No.17, 2014 Comparative Economic Analysis of Upland and Lowland Rice Production in Izzi Local Government Area of Ebonyi State. NWINYA, C. E., OBIENUSI, E. A. & ONUOHA, D. C. Department of Geography and Meteorology, Faculty of Environmental Sciences, Nnamdi Azikiwe University Awka, Nigeria. P. M. B. 5025, Awka, Nigeria. ABSTRACT A study on comparative economic analysis of upland and lowland rice production in Izzi Local Government Area was carried out. A total of 112 rice farmers were interviewed (56 from upland rice and 56 from lowland rice) in the study area using multistage random sampling techniques. The result of gross-margin analysis revealed that upland rice is more profitable than lowland rice as justified by 75% and 51% respectively as was calculated from gross-margin. Linear and exponential forms of the four functional form of regression analysis were chosen as the lead equation for socio-economic factors and production factors respectively. From the findings, it was established that upland rice production is more profitable than lowland rice production. The study therefore recommended the provision of capital, input subsidy, market and weather information, strengthening of farmers by disseminating information and assisting them adopt improved packages for rice production as ways to enhance rice production in the area. 1.0 Introduction 1.1 Background to the Study Rice has become a strategic food security crop in Nigeria today with the country being the largest producer and consumer in West Africa, producing an average of 3.4 million metric tons ((MT) of paddy rice, equivalent to 1.8 million metric tons of milled rice (Daramola 2005; UNEP 2005). -

From the Sierra to the Sea the Ecological History of the San Francisco Bay-Delta Watershed

From the Sierra to the Sea The Ecological History of the San Francisco Bay-Delta Watershed © 1998 The Bay Institute of San Francisco Second printing, July 2003 The Bay Institute of San Francisco is a non-profit research and advocacy organization which works to protect and restore the ecosystem of the San Francisco Bay/Delta estuary and its watershed. Since 1981, the Institute’s policy and technical staff have led programs to protect water quality and endangered species, reform state and federal water management, and promote comprehensive ecological restoration in the Bay/Delta. Copies of this report can be ordered for $40.00 (includes shipping and handling) from: The Bay Institute of San Francisco 500 Palm Drive Novato, CA 94949 Phone: (415) 506-0150 Fax: (415) 506-0155 www.bay.org The cover is taken from an engraving showing the entrance to the middle fork of the Sacramento River near modern-day Steamboat Slough, in C. Ringgold’s 1852 series of navigational charts and sailing directions for San Francisco Bay and Delta. Printed on recycled paper From the Sierra to the Sea The Ecological History of the San Francisco Bay-Delta Watershed July 1998 The Bay Institute FROM THE SIERRA TO THE SEA: THE ECOLOGICAL HISTORY OF THE SAN FRANCISCO BAY-DELTA WATERSHED Table of Contents Page CONTRIBUTORS AND ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS................................................................. vii EXECUTIVE SUMMARY....................................................................................................... ES-1 CHAPTER ONE: INTRODUCTION I. Background....................................................................................................... -

Hunter-Central Rivers Region 0 25 50 75 Km

State of the catchments 2010 Riverine ecosystems Hunter–Central Rivers region State Plan target By 2015 there is an improvement in the condition of riverine ecosystems. Background The Hunter–Central Rivers region covers 37,000 km2 of the east coast of New South Wales; from Taree in the north, to Gosford and the coastal waterways of the Central Coast in the south, and from Newcastle in the east to the Merriwa Plateau and Great Dividing Range in the west (Figure 1). The region’s major waterways are the Manning, Karuah and Hunter rivers and the coastal waterways of Wallis Lake, Port Stephens, Lake Macquarie, Tuggerah Lake and Brisbane Water. The Manning River flows over a length of 250 km and its tributaries rise immediately north of and within Barrington Tops at an altitude of 1400 to 1500 m above sea level. The major tributaries of the Manning catchment are the Barnard and Nowendoc rivers, rising in the northern part of the valley, and the Barrington and Gloucester rivers, rising in the southern highland areas. The Barrington and Gloucester rivers flow in a north-easterly direction and the Barnard River in an easterly direction through alluvial valleys before entering the Manning River. In the lower reaches, the river is tidal and is often saline to Abbotts Falls near Wingham. A detailed technical report describes the methods used to derive the information contained in this report. At the time of publication of the State of the catchments (SOC) 2010 reports, the technical reports were being prepared for public release. When complete, they will be available on the NOW website: www.water.nsw.gov.au. -

UPLAND RICE: a GLOBAL PERSPECTIVE Shown in Figure 2, Is Derived from the Map, Southeast Asia — Rice Area Planted by Culture Type, Developed by Huke (9)

books (JPEG Image, 685x1026 pixels) - Scaled (72%) http://books.google.com/books?id=DlRlYq5u-J8C&pg=PP1&img=1&zo... 1 of 1 10/1/2009 8:26 AM UPLAND RICE A Global Perspective P. C. GUPTA J. C. O'TOOLE 1986 International Rice Research Institute Los Baños, Laguna, Philippines P.O. Box 933, Manila, Philippines The International Rice Research Institute (IRRI) was established in 1960 by the Ford and Rockfeller Foundations with the help and approval of the Government of the Philippines. Today IRRI is one of the 13 nonprofit international research and training centers supported by the Consultative Group on International Agricultural Research (CGIAR). The CGIAR is sponsored by the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) of the United Nations, the International Bank for Reconstruction and Develop- ment (World Bank), and the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). The CGIAR consists of 50 donor countries, international and regional organizations, and private foundations. IRRI receives support, through the CGIAR, from a number of donors including: the Asian Development Bank, the European Economic Com- munity, the Ford Foundation, the International Development Research Centre, the International Fund for Agricultural Development, the OPEC Special Fund, the Rockefeller Foundation, the United Nations Develop- ment Programme, the World Bank, and the international aid agencies of the following governments: Australia, Canada, China, Denmark, France, Federal Republic of Germany, India, Italy, Japan, Mexico, Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Philippines, Saudi Arabia, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, United Kingdom, and United States. The responsibility for this publication rests with the International Rice Research Institute. Copyright © International Rice Research Institute 1986 All rights reserved. -

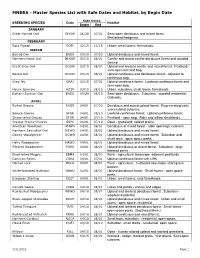

Master Species List with Safe Dates and Habitat, by Begin Date

MNBBA - Master Species List with Safe Dates and Habitat, by Begin Date Safe Dates BREEDING SPECIES Code Habitat Begin End JANUARY Great Horned Owl GHOW 01/20 07/01 Semi-open deciduous and mixed forest. Shelterbed/hedgerow. FEBRUARY Rock Pigeon ROPI 02/15 11/15 Urban; small towns; farmsteads. MARCH Barred Owl BADO 03/10 07/20 Upland deciduous and mixed forest. Northern Hawk Owl NHOW 03/15 08/01 Conifer and mixed conifer-deciduous forest and wooded swamp Great Gray Owl GGOW 03/15 08/01 Upland and lowland conifer and mixed forest. Peatland - semi-open forested bog. Boreal Owl BOOW 03/15 08/01 Upland coniferous and deciduous forest - adjacent to coniferous bog. Gray Jay GRAJ 03/15 07/01 Upland coniferous forest. Lowland coniferous forest and semi-open bog. House Sparrow HOSP 03/15 08/10 Urban, suburban, small towns, farmsteads Eastern Screech-Owl EASO 03/20 08/10 Semi-open deciduous. Suburban - wooded residential. Orchards. APRIL Ruffed Grouse RUGR 04/01 07/20 Deciduous and mixed upland forest. Regenerating/early successional cutovers. Spruce Grouse SPGR 04/01 08/10 Lowland coniferous forest. Upland coniferous forest. Sharp-tailed Grouse STGR 04/01 07/10 Peatland - open bog. Alder and willow shrublands. Greater Prairie-Chicken GRPC 04/01 07/10 Open - grassland; upland prairie. American Woodcock AMWO 04/01 08/01 Deciduous or mixed forest - alder openings; cutovers. Northern Saw-whet Owl NSWO 04/01 08/01 Upland deciduous and mixed forest. Downy Woodpecker DOWO 04/01 08/01 Upland deciduous and mixed forest. Suburban and small town - open space parks.