'Soul on Trent'

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

BTN6916 LMW NORTHERN SOUL ENTS GUIDE SK.Indd

22-25 SEPT 2017 20-23 SEPT 2019 SKEGNESS RESORT GLORIACELEBRATING 60 YEARS JONES OF MOTOWN BOBBY BROOKS WILSON BRENDA HOLLOWAY EDDIE HOLMAN CHRIS CLARK THE FLIRTATIONS TOMMY HUNT THE SIGNATURES FT. STEFAN TAYLOR PAUL STUART DAVIES•JOHNNY BOY PLUS MANY MORE WELCOME TO THE HIGHLIGHTS As well as incredible headliners and legendary DJs, there are loads WORLD’S BIGGEST AND more soulful events to get involved in: BEST NORTHERN SOUL ★ Dance competition with Russ Winstanley and Sharon Sullivan ★ Artist meet and greets SURVIVORS WEEKENDER ★ Shhhh... Battle of the DJs Silent Disco ★ Tune in to Northern Soul BBC – Butlin’s Broadcasting Company Original Wigan Casino jock and founder of the Soul Survivors Weekender, with Russ! Russ Winstanley, has curated another jam-packed few days for you. It’s an ★ incredible line-up with soul legends fl own in from around the world plus a Northern Soul Awards and Dance Competition host of your favourite soul spinners. We’re celebrating Motown Records 60th Anniversary in 2019. To mark this special occasion we have some of the original Motown ladies gracing the stage to celebrate this milestone birthday. SATURDAY 14.00 REDS Meet and Greet with Eddie Holman, Bobby Brooks Wilson, Tommy Hunt Brenda Holloway, Chris Clark and Gloria Jones will also be joining us for a Q&A session, together with Motown afi cionado, Sharon Davies, on Sunday afternoon in Reds. Not to be missed!! SUNDAY 14.00 REDS Don’t miss the Northern Soul dance classes, DJ Battles, Northern Soul Q&A with Brenda Holloway, Chris Clark, Gloria Jones and Sharon Davis awards and dance competitions across the weekend and be sure to look Hosted by Russ Winstanley and Ian Levine, followed by a meet and greet out for limited edition, souvenir vinyl and merch in the Skyline record stall. -

Clarky List 50 31/07/2012 13:06 Page 1

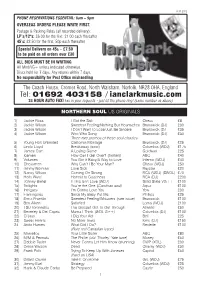

Clarky List 51_Clarky List 50 31/07/2012 13:06 Page 1 JULY 2012 PHONE RESERVATIONS ESSENTIAL : 8am – 9pm OVERSEAS ORDERS PLEASE WRITE FIRST. Postage & Packing Rates (all recorded delivery): LP’s/12"s: £6.00 for the first, £1.00 each thereafter 45’s: £2.50 for the first, 50p each thereafter Special Delivery on 45s – £7.50 to be paid on all orders over £30 ALL BIDS MUST BE IN WRITING All Mint/VG+ unless indicated otherwise. Discs held for 7 days. Any returns within 7 days. No responsibility for Post Office mis han dling The Coach House, Cromer Road, North Walsham, Norfolk, NR28 0HA, England Tel: 01692 403158 / ianclarkmusic.com 24 HOUR AUTO FAX! Fax in your requests - just let the phone ring! (same number as above) NORTHERN SOUL US ORIGINALS 1) Jackie Ross I Got the Skill Chess £8 2) Jackie Wilson Sweetest Feeling/Nothing But Heartaches Brunswick (DJ) £30 3) Jackie Wilson I Don’t Want to Lose/Just Be Sincere Brunswick (DJ £35 4) Jackie Wilson Who Who Song Brunswick (DJ) £30 Three rare promos of these soul classics 5) Young Holt Unlimited California Montage Brunswick (DJ) £25 6) Linda Lloyd Breakaway (swol) Columbia (WDJ) £175 7) James Carr A Losing Game Goldwax £25 8) Icemen How Can I Get Over? (brilliant) ABC £40 9) Volumes You Got it Baby/A Way to Love Inferno (WDJ) £40 10) Chessmen Why Can’t I Be Your Man? Chess (WDJ) £50 11) Jimmy Norman Love Sick Raystar £20 12) Nancy Wilcox Coming On Strong RCA (WDJ) (SWOL) £70 13) Herb Ward Honest to Goodness RCA (DJ) £200 14) Johnny Bartel If This Isn’t Love (WDJ) Solid State VG++ £100 15) Twilights -

Whole Day Download the Hansard

Tuesday Volume 623 21 March 2017 No. 128 HOUSE OF COMMONS OFFICIAL REPORT PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES (HANSARD) Tuesday 21 March 2017 © Parliamentary Copyright House of Commons 2017 This publication may be reproduced under the terms of the Open Parliament licence, which is published at www.parliament.uk/site-information/copyright/. 753 21 MARCH 2017 754 Mr Hunt: The one simple thing the Government are House of Commons not going to do is refuse to listen to what the British people said when they voted on 23 June. We will do what they said—it is the right thing to do. However, the Tuesday 21 March 2017 right hon. Gentleman is absolutely right to highlight the vital role that the around 10,000 EU doctors in the The House met at half-past Eleven o’clock NHS play in this country. I can reassure him that the number of doctors joining the NHS from the EU was higher in the four months following the referendum PRAYERS result than in the same four months the previous year. 23. [909376] Helen Whately (Faversham and Mid Kent) [MR SPEAKER in the Chair] (Con): Does my right hon. Friend agree that Kent, with its excellent academic institutions and strong life sciences sector, would be an ideal location for a new medical school, and will he support emerging plans to Oral Answers to Questions establish one? Mr Hunt: I can absolutely confirm that the garden of England would be an ideal place for a new medical HEALTH school—alongside many other parts of the country that are actively competing to start medical schools as a The Secretary of State was asked— result of the expansion in doctor numbers. -

Did Wigan Have a Northern Soul?

Did Wigan have a Northern Soul? Introduction The town of Wigan in Lancashire, England, will forever be associated with the Northern Soul scene because of the existence of the Casino Club, which operated in the town between 1973 and 1981. By contrast, Liverpool just 22 miles west, with the ‘the most intensely aware soul music Black Community in the country’, (Cohen, 2007, p.31 quoting from Melody Maker, 24 July 1976) remained immune to the attractions of Northern Soul and its associated scene, music, subculture and mythology. Similarly, the city of Manchester has been more broadly associated with punk and post-punk. Wigan was and remains indelibly connected to the Northern Soul scene with the Casino representing a symbolic location for reading the geographical, class and occupational basis of the scene’s practitioners. The club is etched into the history, iconography, and mythology of Northern Soul appearing in the academic and more general literature, television documentaries, memoirs, autobiographies and feature films. This chapter seeks to explore the relationship between history, place, class, industrialisation, mythology and nostalgia in terms of Wigan, the Casino Club and the Northern Soul scene. It asks the question: did Wigan have a northern soul? This is explored through the industrial and working-class history of the town and the place of soul music in its post-war popular culture. More broadly, it complements the historical literature on regional identity identifying how Northern Soul both complemented and challenged orthodox readings of Wigan as a town built on coal and cotton that by the 1970s was entering a process of deindustrialisation. -

Diggin' You Like Those Ol' Soul Records: Meshell Ndegeocello and the Expanding Definition of Funk in Postsoul America

Diggin’ You Like Those Ol’ Soul Records 181 Diggin’ You Like Those Ol’ Soul Records: Meshell Ndegeocello and the Expanding Definition of Funk in Postsoul America Tammy L. Kernodle Today’s absolutist varieties of Black Nationalism have run into trouble when faced with the need to make sense of the increasingly distinct forms of black culture produced from various diaspora populations. The unashamedly hybrid character of these black cultures continually confounds any simplistic (essentialist or antiessentialist) understanding of the relationship between racial identity and racial nonidentity, between folk cultural authenticity and pop cultural betrayal. Paul Gilroy1 Funk, from its beginnings as terminology used to describe a specific genre of black music, has been equated with the following things: blackness, mascu- linity, personal and collective freedom, and the groove. Even as the genre and terminology gave way to new forms of expression, the performance aesthetic developed by myriad bands throughout the 1960s and 1970s remained an im- portant part of post-1970s black popular culture. In the early 1990s, rhythm and blues (R&B) splintered into a new substyle that reached back to the live instru- mentation and infectious grooves of funk but also reflected a new racial and social consciousness that was rooted in the experiences of the postsoul genera- tion. One of the pivotal albums advancing this style was Meshell Ndegeocello’s Plantation Lullabies (1993). Ndegeocello’s sound was an amalgamation of 0026-3079/2013/5204-181$2.50/0 American Studies, 52:4 (2013): 181-204 181 182 Tammy L. Kernodle several things. She was one part Bootsy Collins, inspiring listeners to dance to her infectious bass lines; one part Nina Simone, schooling one about life, love, hardship, and struggle in post–Civil Rights Movement America; and one part Sarah Vaughn, experimenting with the numerous timbral colors of her voice. -

Sooloos Collections: Advanced Guide

Sooloos Collections: Advanced Guide Sooloos Collectiions: Advanced Guide Contents Introduction ...........................................................................................................................................................3 Organising and Using a Sooloos Collection ...........................................................................................................4 Working with Sets ..................................................................................................................................................5 Organising through Naming ..................................................................................................................................7 Album Detail ....................................................................................................................................................... 11 Finding Content .................................................................................................................................................. 12 Explore ............................................................................................................................................................ 12 Search ............................................................................................................................................................. 14 Focus .............................................................................................................................................................. -

Northern Soul Also by Ron Silliman

Northern Soul Also by Ron Silliman Poetry Revelator (being degree 1 of Universe) The Alphabet The Age of Huts (compleat) Tjanting Memoirs & Collaborations The Grand Piano Under Albany Leningrad Criticism The New Sentence (editor) In the American Tree Ron Silliman Northern Soul being degree 10 of Universe Shearsman Books First published in the United Kingdom in 2014 by Shearsman Books 50 Westons Hill Drive Emersons Green BRISTOL BS16 7DF Shearsman Books Ltd Registered Office 30–31 St. James Place, Mangotsfield, Bristol BS16 9JB (this address not for correspondence) www.shearsman.com ISBN 978-1-84861-319-5 Copyright © Ron Silliman, 2014. The right of Ron Silliman to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyrights, Designs and Patents Act of 1988. All rights reserved. Northern Soul For Barney Up Quay St to Deansgate then over to Victoria Station, Northern Rail West to Liverpool grey clouds pillowing the sky No height in these fields yet whatever they’re growing Hedge row as fencing An older station at Newton-le-Willows brick office padlocked but the chairs on the platform bright yellow vinyl then the backsides of row housing with thin slivers of yards School fields without baseball diamonds Magpies mistaken for mockingbirds Blood pudding salad full of rocket planespotter in an antiaircraft 9 unit, learning first to drive a tank over the Egyptian desert then determining never to leave England again Sharp shadow over the page writing into the dark Notice is hereby given that it is proposed -

Download the Paul Donnelly Transcript

Northern Soul Scene Project Paul Donnelly (PD) interviewed by Jason Mitchell (JM) on 1st April 2020 JM: First of all, I've sent you some bits and pieces ahead of time. Did you get a chance just to have a little look at those? PD: Um, was that the documents I need to sign? JM: Yeah. And we kind of just want to make sure that you've read them, and it's kind of like almost an email signature. So if you're saying that you've looked at them and you kind of agree in principle… PD: Fine. I've read them and I'm quite happy. So I shall send an email back tomorrow saying read, um, fine, okay. It's just I couldn't sign them and send them back to you, that’s all. JM: No, no, that's great. That’s fine. PD: Okay. JM: And it's the…it's the First of April today, 2020. My name’s Jason Mitchell, I'm interviewing you. And first of all, if I could ask you for your first name. PD: Paul. JM: And could you spell that for me? PD: P A U L. JM: Lovely. And your surname? PD: Donnelly. JM: And could you spell that for me please? PD: D O N N E L L Y. JM: Perfect. And obviously it's a telephone interview as opposed to a one to one due to the current situation. It’s for the Northern Soul Project, er, which is run by Jumped Up Theatre Company. -

LIST #801 MONDAY 16Th AUGUST 2021

ANGLO AMERICAN TEL: 01706 818604 PO BOX 4 , TODMORDEN Email : [email protected] LANCS, OL14 6DA. PayPal: [email protected] UNITED KINGDOM Website:www.raresoulvinyl.co.uk SALES LIST #801 MONDAY 16th AUGUST 2021 NEW FORTNIGHTLY RARE SOUL AUCTION ! Auction ends THURSDAY 26th AUGUST at 6.00pm (18.00) Welcome to our new situation which offers two auctions per month (of which this is the 2nd). Usual circumstances apply – no extensions, no drop-downs. Offered price at the finishing time is the price payable. Hope that is clear. Some interesting items as usual, and many thanks for your attention. MIN. BID AUGUST RARE SOUL AUCTION #2 A DOTY ROY YOU GOT MY BOY PIC 1 124 D VG++ 400 One of many Huey Meaux labels (Jetstream, Tribe, Crazy Cajun, etc.), not too much black music on this one but the few releases of that genre seem to be scarce – as is the case with this 1966 female mover from a singer who only recorded one other time as far as we can tell. B THE EBONY’S I CAN’T HELP BUT LOVE YOU AVIS 1001 VG++ 300 It is difficult not to believe that this is not the group that had tremendous seventies releases on Philadelphia International but various sources do not recognise this as the group’s first effort in 1966. We absolutely believe it to be them. Two great sides are produced by Ray Sharp and Roland Chambers whatever the group’s identity. The storming ‘I Can’t Help’ is backed by a very neat midtempo item which points heavily towards their future sound. -

General Coporation Tax Allocation Percentage Report 2003

2003 General Corporation Tax Allocation Percentage Report Page - 1- @ONCE.COM INC .02 A AND J TITLE SEARCHING CO INC .01 @RADICAL.MEDIA INC 25.08 A AND L AUTO RENTAL SERVICES INC 1.00 @ROAD INC 1.47 A AND L CESSPOOL SERVICE CORP 96.51 "K" LINE AIR SERVICE U.S.A. INC 20.91 A AND L GENERAL CONTRACTORS INC 2.38 A OTTAVINO PROPERTY CORP 29.38 A AND L INDUSTRIES INC .01 A & A INDUSTRIAL SUPPLIES INC 1.40 A AND L PEN MANUFACTURING CORP 53.53 A & A MAINTENANCE ENTERPRISE INC 2.92 A AND L SEAMON INC 4.46 A & D MECHANICAL INC 64.91 A AND L SHEET METAL FABRICATIONS CORP 69.07 A & E MANAGEMENT SYSTEMS INC 77.46 A AND L TWIN REALTY INC .01 A & E PRO FLOOR AND CARPET .01 A AND M AUTO COLLISION INC .01 A & F MUSIC LTD 91.46 A AND M ROSENTHAL ENTERPRISES INC 51.42 A & H BECKER INC .01 A AND M SPORTS WEAR CORP .01 A & J REFIGERATION INC 4.09 A AND N BUSINESS SERVICES INC 46.82 A & M BRONX BAKING INC 2.40 A AND N DELIVERY SERVICE INC .01 A & M FOOD DISTRIBUTORS INC 93.00 A AND N ELECTRONICS AND JEWELRY .01 A & M LOGOS INTERNATIONAL INC 81.47 A AND N INSTALLATIONS INC .01 A & P LAUNDROMAT INC .01 A AND N PERSONAL TOUCH BILLING SERVICES INC 33.00 A & R CATERING SERVICE INC .01 A AND P COAT APRON AND LINEN SUPPLY INC 32.89 A & R ESTATE BUYERS INC 64.87 A AND R AUTO SALES INC 16.50 A & R MEAT PROVISIONS CORP .01 A AND R GROCERY AND DELI CORP .01 A & S BAGEL INC .28 A AND R MNUCHIN INC 41.05 A & S MOVING & PACKING SERVICE INC 73.95 A AND R SECURITIES CORP 62.32 A & S WHOLESALE JEWELRY CORP 78.41 A AND S FIELD SERVICES INC .01 A A A REFRIGERATION SERVICE INC 31.56 A AND S TEXTILE INC 45.00 A A COOL AIR INC 99.22 A AND T WAREHOUSE MANAGEMENT CORP 88.33 A A LINE AND WIRE CORP 70.41 A AND U DELI GROCERY INC .01 A A T COMMUNICATIONS CORP 10.08 A AND V CONTRACTING CORP 10.87 A A WEINSTEIN REALTY INC 6.67 A AND W GEMS INC 71.49 A ADLER INC 87.27 A AND W MANUFACTURING CORP 13.53 A AND A ALLIANCE MOVING INC .01 A AND X DEVELOPMENT CORP. -

NEW YORK NIGHT TRAIN's SOUL CLAP and DANCE-OFF

NEW YORK NIGHT TRAIN’S SOUL CLAP and DANCE-OFF WHAT IS IT? For two straight years New York Night Train's Soul Clap and Dance-Off has reigned as North America’s most popular soul party – by far playing to more people in more places and generating more capital than any of its contemporaries. The concept is simple - all night dancing to wild 45s of subterranean maximum rock and soul DJ Mr. Jonathan Toubin and, in the middle, a $100 dance contest judged by a panel of local celebrities. Recession-friendly mass entertainment with a $5 door price, the dance party/spectacle not only sells beyond capacity at home, but has brought its excitement to domestic markets all the way from Portland, Oregon to Portland, Maine and internationally from Tel Aviv to Mexico City - including monthly residencies in New York, Chicago, LA, San Francisco, Oakland, and PDX. Also the Dance-Off portion features judges from every edge of music and culture from classic subcultural icons like Mike Watt and Jello Biafra, to rock stars Andrew Van Wyngarden (MGMT) and Nick Zinner (Yeah Yeah Yeahs), to interesting cultural figures like Karla LaVey (Satanic Priestess) and Candidate Matt Gonzalez (Green Party Vice Presidential) to your favorite neighborhood heroes. Catch The Soul Clap! WHY IS TONIGHT DIFFERENT THAN ALL OTHERS? Because New York Night Train, Mr. Jonathan Toubin, and the Soul Clap emerged not from the mod or soul scene but the punk, post-punk, and general independent rock'n'roll underground, Soul Clap grew as a uniting force for various subcultural groups. -

A Catalyst for Self-Expression Through the Lens: a Catalyst for Self-Expression Updates

Through the Lens: A Catalyst for Self-Expression Through the Lens: A Catalyst for Self-Expression Updates Updates: - Changed Punk to Northern Soul. Beyond the obvious. Less known about. - Exploring the subculture. Characteristics. - Difficulties with combining the research with the concept: lenses. Developing a tool for self-expression. - Becomes rigid, difficult for the user to be productive with it. - More of a book about a subculture, less about the self-expression of the tool - How can I use the knowledge I have to develop it into something workable and more fluid? - I have thought about potentially putting a song on each page to create a sort of playlist that can accompany the visual pieces. For demonstration purposes I have added these songs to the bottom right hand corner of the pages of my deck. Through the Lens: A Catalyst for Self-Expression A Brief History Northern Soul emerged in the 1960s from the British Mod scene. American blues, soul and motown records were imported from America and played in underground clubs across the North. Arguably, the scene started in Manchester at The Twisted Wheel, with the Blackpool Mecca, The Golden Torch in Stoke-On-Trent and the infamous Wigan Casino forming shortly after. People would travel many miles to see DJs perform at these dancehalls that had the most rare and obscure records. The DJs themsleves were in competition. They would travel to America in search of the next best record that nobody else had, so that people would choose to come to their nights, rather than other DJs. The audience was largely white and working class.