Typology for Abinadi: Exegesis • 105

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

L17 a Seer … Becometh a Great Benefit to His Fellow Beings.Pages

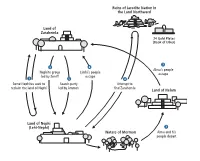

Lesson 17: “A Seer … Becometh a Great Benefit to His Fellow Beings” (Mos. 7–11) L17 Study Guide Purpose: To encourage us to follow the counsel of Church leaders, particularly our prophets, seers, and revelators” See the diagram and explanation of the Land of Lehi-Nephi. 1. Ammon and his brethren find Limhi and his people. Ammon teaches Limhi of the importance of a seer. (Mosiah 7-8.) • Mos. 7:7-11 Ammon and his15 cohorts are taken captive by King Limhi’s guards. • Mos. 7:12-15 Ammon tells his story and King Limhi rejoices. • Mos. 7:17-20, 29-33 What principles does King Limhi teach his people? What does this tell us about King Limhi? • Mos. 8:7 King Limhi reports that he had sent out a scouting part of 43 persons to find Zarahemla. • Mos. 8:8-12 They found 24 gold plates and King Limhi desires they be translated. Why would it be helpful for Limhi’s people, and us, to “know the cause of [the] destruction” of the Jaredites? • Mosiah 8:13-16 Ammon told Limhi of a king who was a prophet and seer. • Mosiah 8:13, 17-18 How do prophets, seers, and revelators fulfill these roles? How have latter-day prophets, seers, and revelators been “a great benefit” to you? †1. Elder Boyd K. Packer †2. Elder John A. Widstoe 2. The record of Zeniff recounts a brief history of Zeniff’s people. (Mosiah 9-10.) Chapters 9 through 22 “of the book of Mosiah contain a history of the people who left Zarahemla to return to the land of Nephi. -

“They Are of Ancient Date”: Jaredite Traditions and the Politics of Gadianton's Dissent

Brigham Young University BYU ScholarsArchive Faculty Publications 2020-8 “They Are of Ancient Date”: Jaredite Traditions and the Politics of Gadianton’s Dissent Dan Belnap Brigham Young University, [email protected] Daniel L. Belnap Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/facpub Part of the Mormon Studies Commons BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Belnap, Dan and Belnap, Daniel L., "“They Are of Ancient Date”: Jaredite Traditions and the Politics of Gadianton’s Dissent" (2020). Faculty Publications. 4479. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/facpub/4479 This Book Chapter is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. ILLUMINATING THE RECORDS Edited by Daniel L. Belnap Published by the Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, Provo, Utah, in cooper- ation with Deseret Book Company, Salt Lake City. Visit us at rsc.byu.edu. © 2020 by Brigham Young University. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America by Sheridan Books, Inc. DESERET BOOK is a registered trademark of Deseret Book Company. Visit us at DeseretBook.com. Any uses of this material beyond those allowed by the exemptions in US copyright law, such as section 107, “Fair Use,” and section 108, “Library Copying,” require the written permission of the publisher, Religious Studies Center, 185 HGB, Brigham Young University, Provo, Utah 84602. The views expressed herein are the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the position of Brigham Young University or the Religious Studies Center. -

Land of Zarahemla Land of Nephi (Lehi-Nephi) Waters of Mormon

APPENDIX Overview of Journeys in Mosiah 7–24 1 Some Nephites seek to reclaim the land of Nephi. 4 Attempt to fi nd Zarahemla: Limhi sends a group to fi nd They fi ght amongst themselves, and the survivors return to Zarahemla and get help. The group discovers the ruins of Zarahemla. Zeniff is a part of this group. (See Omni 1:27–28 ; a destroyed nation and 24 gold plates. (See Mosiah 8:7–9 ; Mosiah 9:1–2 .) 21:25–27 .) 2 Nephite group led by Zeniff settles among the Lamanites 5 Search party led by Ammon journeys from Zarahemla to in the land of Nephi (see Omni 1:29–30 ; Mosiah 9:3–5 ). fi nd the descendants of those who had gone to the land of Nephi (see Mosiah 7:1–6 ; 21:22–24 ). After Zeniff died, his son Noah reigned in wickedness. Abinadi warned the people to repent. Alma obeyed Abinadi’s message 6 Limhi’s people escape from bondage and are led by Ammon and taught it to others near the Waters of Mormon. (See back to Zarahemla (see Mosiah 22:10–13 ). Mosiah 11–18 .) The Lamanites sent an army after Limhi and his people. After 3 Alma and his people depart from King Noah and travel becoming lost in the wilderness, the army discovered Alma to the land of Helam (see Mosiah 18:4–5, 32–35 ; 23:1–5, and his people in the land of Helam. The Lamanites brought 19–20 ). them into bondage. (See Mosiah 22–24 .) The Lamanites attacked Noah’s people in the land of Nephi. -

Conversion of Alma the Younger

Conversion of Alma the Younger Mosiah 27 I was in the darkest abyss; but now I behold the marvelous light of God. Mosiah 27:29 he first Alma mentioned in the Book of Mormon Before the angel left, he told Alma to remember was a priest of wicked King Noah who later the power of God and to quit trying to destroy the Tbecame a prophet and leader of the Church in Church (see Mosiah 27:16). Zarahemla after hearing the words of Abinadi. Many Alma the Younger and the four sons of Mosiah fell people believed his words and were baptized. But the to the earth. They knew that the angel was sent four sons of King Mosiah and the son of the prophet from God and that the power of God had caused the Alma, who was also called Alma, were unbelievers; ground to shake and tremble. Alma’s astonishment they persecuted those who believed in Christ and was so great that he could not speak, and he was so tried to destroy the Church through false teachings. weak that he could not move even his hands. The Many Church members were deceived by these sons of Mosiah carried him to his father. (See Mosiah teachings and led to sin because of the wickedness of 27:18–19.) Alma the Younger. (See Mosiah 27:1–10.) When Alma the Elder saw his son, he rejoiced As Alma and the sons of Mosiah continued to rebel because he knew what the Lord had done for him. against God, an angel of the Lord appeared to them, Alma and the other Church leaders fasted and speaking to them with a voice as loud as thunder, prayed for Alma the Younger. -

King Benjamin and the Feast of Tabernacles

King Benjamin and the Feast of Tabernacles John A. Tvedtnes A portion of the brass plates brought by Lehi to the New World contained the books of Moses (1 Nephi 5:10-13). Nephi and other Book of Mormon writers stressed that they obeyed the laws given therein: “And we did observe to keep the judgments, and the statutes, and the commandments of the Lord in all things according to the law of Moses” (2 Nephi 5:10). But aside from sacrice2 and the Ten Commandments,3 we have few explicit details regarding the Nephite observance of the Mosaic code. One would expect, for example, some mention of the festivals which played such an important role in the religious observances of ancient Israel. Though the Book of Mormon mentions no religious festivals by name, it does detail many signicant Nephite assemblies. One of the more noteworthy of the Nephite ceremonies was the coronation of the second Mosiah by his father, Benjamin.4 Some years ago, Professor Hugh Nibley outlined the similarities between this Book of Mormon account and ancient Middle Eastern coronation rites.5 He pointed out that these rites took place at the annual New Year festival, when the people were placed under covenant of obedience to the monarch. My own research further explores the Israelite coronation/New Year rites, and aims to complement other scholarly studies of the ceremonial context of Benjamin’s speech. THE SABBATICAL FEASTS In the sacred calendar, the Israelite new year began with the month of Abib (later called Nisan), in the spring (end March/beginning April).6 This month encompassed the feasts of Passover (beginning at sundown on the fourteenth day) and Unleavened Bread (fourteenth through twenty-first days), and included “holy convocations,” analogous to the Latter-day Saint April general conference (Leviticus 23:4-8). -

Joseph Smith and Diabolism in Early Mormonism 1815-1831

Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU All Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate Studies 5-2021 "He Beheld the Prince of Darkness": Joseph Smith and Diabolism in Early Mormonism 1815-1831 Steven R. Hepworth Utah State University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/etd Part of the History of Religion Commons Recommended Citation Hepworth, Steven R., ""He Beheld the Prince of Darkness": Joseph Smith and Diabolism in Early Mormonism 1815-1831" (2021). All Graduate Theses and Dissertations. 8062. https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/etd/8062 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. "HE BEHELD THE PRINCE OF DARKNESS": JOSEPH SMITH AND DIABOLISM IN EARLY MORMONISM 1815-1831 by Steven R. Hepworth A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in History Approved: Patrick Mason, Ph.D. Kyle Bulthuis, Ph.D. Major Professor Committee Member Harrison Kleiner, Ph.D. D. Richard Cutler, Ph.D. Committee Member Interim Vice Provost of Graduate Studies UTAH STATE UNIVERSITY Logan, Utah 2021 ii Copyright © 2021 Steven R. Hepworth All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT “He Beheld the Prince of Darkness”: Joseph Smith and Diabolism in Early Mormonism 1815-1831 by Steven R. Hepworth, Master of Arts Utah State University, 2021 Major Professor: Dr. Patrick Mason Department: History Joseph Smith published his first known recorded history in the preface to the 1830 edition of the Book of Mormon. -

A Third Jaredite Record: the Sealed Portion of the Gold Plates

Journal of Book of Mormon Studies Volume 11 Number 1 Article 10 7-31-2002 A Third Jaredite Record: The Sealed Portion of the Gold Plates Valentin Arts Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/jbms BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Arts, Valentin (2002) "A Third Jaredite Record: The Sealed Portion of the Gold Plates," Journal of Book of Mormon Studies: Vol. 11 : No. 1 , Article 10. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/jbms/vol11/iss1/10 This Feature Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Book of Mormon Studies by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Title A Third Jaredite Record: The Sealed Portion of the Gold Plates Author(s) Valentin Arts Reference Journal of Book of Mormon Studies 11/1 (2002): 50–59, 110–11. ISSN 1065-9366 (print), 2168-3158 (online) Abstract In the Book of Mormon, two records (a large engraved stone and twenty-four gold plates) contain the story of an ancient civilization known as the Jaredites. There appears to be evidence of an unpublished third record that provides more information on this people and on the history of the world. When the brother of Jared received a vision of Jesus Christ, he was taught many things but was instructed not to share them with the world until the time of his death. The author proposes that the brother of Jared did, in fact, write those things down shortly before his death and then buried them, along with the interpreting stones, to be revealed to the world according to the timing of the Lord. -

Mini-Lesson 3. Helaman 13:24–33

BOOK OF MORMON SEMINARY TEACHER MANUAL—LESSON 113 Mini-Lesson 3. Helaman 13:24–33 Invite a student to read Helaman 13:24–26 aloud. Ask the other students to follow along, looking for how the Nephites responded to the prophets whom the Lord sent to them. Then ask the following questions: • How did the Nephites respond to the prophets whom the Lord sent to them? • Why do you think some people become angry when a prophet encourages them to repent? Invite a student to read Helaman 13:27–28 aloud. Ask the other students to follow along, looking for the teachings the Nephites wanted to hear. • What teachings did the Nephites want to hear? • Why might these kinds of teachings appeal to people? • What are some examples of similar teachings and attitudes in our day? Invite a student to read Helaman 13:30–33 aloud. Ask the other students to follow along, looking for what the Nephites would experience if they rejected the words of the Lord’s prophets. • What principle can we learn from these verses about what will happen if we reject the words of the Lord’s prophets? (Help students identify the following principle: If we reject the words of the Lord’s prophets, we will experience regret and sorrow. Invite students to consider writing this principle in their scriptures near verses 30–33.) • How might rejecting a prophet’s counsel lead someone to experience regret and sorrow? Ask a student to read aloud the following statement by President Ezra Taft Benson (1899–1994): “How we respond to the words of a living prophet when he tells us what we need to know, but would rather not hear, is a test of our faithfulness” (Ezra Taft Benson, “ Fourteen Funda- mentals in Following the Prophet ” [Brigham Young University devotional, Feb. -

May 2015 Ensign

By Elder Michael T. Ringwood My Book of Mormon hero is a Of the Seventy perfect example of a wonderful and blessed soul who was truly good and without guile. Shiblon was one of the sons of Alma the Younger. We are more familiar with his brothers Helaman, Truly Good and who would follow his father as the keeper of the records and the prophet of God, and Corianton, who gained some notoriety as a missionary who without Guile needed some counsel from his father. To Helaman, Alma wrote 77 verses The good news of the gospel of Jesus Christ is that the desires of our (see Alma 36–37). To Corianton, Alma hearts can be transformed and our motives can be educated and refined. dedicated 91 verses (see Alma 39–42). To Shiblon, his middle son, Alma wrote a mere 15 verses (see Alma 38). Yet his words in those 15 verses are powerful nfortunately, there was a time in In October, President Dieter F. and instructive. my life when I was motivated by Uchtdorf said: “Over the course of “And now, my son, I trust that I shall Utitles and authority. It really began my life, I have had the opportunity to have great joy in you, because of your innocently. As I was preparing to serve rub shoulders with some of the most steadiness and your faithfulness unto a full-time mission, my older brother competent and intelligent men and God; for as you have commenced in was made a zone leader in his mission. women this world has to offer. -

Priesthood Concepts in the Book of Mormon

s u N S T O N E Unique perspectives on Church leadership and organi zation PRIESTHOOD CONCEPTS IN THE BOOK OF MORMON By Paul James Toscano THE BOOK OF MORMON IS PROBABLY THE EARLI- people." The phrasing and context of this verse suggests that est Mormon scriptural text containing concepts relating to boththe words "priest" and "teacher" were not used in our modern the structure and the nature of priesthood. This book, printed sense to designate offices within a priestly order or structure, between August 1829 and March 1830, is the first published such as deacon, priest, bishop, elder, high priest, or apostle. scripture of Mormonism but was preceded by seventeen other Nor were they used to designate ecclesiastical offices, such as then unpublished revelations, many of which eventually appearedcounselor, stake president, quorum president, or Church presi- in the 1833 Book of Commandments and later in the 1835 dent. They appear to refer only to religious functions. Possibly, edition of the Doctrine and Covenants. Prior to their publica- the teacher was one who expounded and admonished the tion, most or all of these revelations existed in handwritten formpeople; the priest ~vas possibly one who mediated between and undoubtedly had limited circulation. God and his people, perhaps to administer the ordinances of While the content of many of these revelations (now sec-the gospel and the rituals of the law of Moses, for we are told tions 2-18) indicate that priesthood concepts were being dis- by Nephi that "notwithstanding we believe in Christ, we keep cussed in the early Church, from 1830 until 1833 the Book the law of Moses" (2 Nephi 25: 24). -

Mosiah Like the Lamanites, Who Know Nothing King Benjamin Teaches Sons About God's Commandments and See Mosiah, Chapter 1 Mysteries

!139 A Plain English Reference to have faltered in unbelief. We would be The Book of Mosiah like the Lamanites, who know nothing King Benjamin teaches sons about God's commandments and See Mosiah, Chapter 1 mysteries. They don't believe these things because they are misguided by This peace among all the people in the their forefathers' false traditions. land of Zarahemla lasted for the rest of Remember this, for these records are King Benjamin's days. He had three true. sons, Mosiah, Helorum and Helaman, and taught them the writing language of And these plates Nephi made, which their forefathers — modified Egyptian. contain our forefathers' words from the time they left Jerusalem until now, are He did this so they would become men also true. Remember to search them of understanding, knowing the diligently so you may profit from them. prophecies the Lord had given their forefathers (engraved on Nephi's I want you to obey God’s commands plates). so you will prosper in the land, according to the promises He made to Benjamin also taught his sons our forefathers." concerning the records engraved on the brass plates, saying, King Benjamin taught many more things to his sons not written here. "My sons, I want you to remember, if it were not for these plates containing As he grew old and realized he would records and commandments, we would soon die, he felt it necessary to confer now be in ignorance, not knowing the the kingdom upon one of his sons. And mysteries of God. It would have been so he called for Mosiah, named after impossible for our forefather Lehi to his grandfather, and said to him, have remembered all these things, and "My son, I want you to make a to have taught them to his children proclamation throughout all the land of without these plates. -

TEACHINGS of the BOOK of MORMON HUGH NIBLEY Semester 2, Lecture 32 Mosiah 8–10 Ammon and Limhi the Record of Zeniff

TEACHINGS OF THE BOOK OF MORMON HUGH NIBLEY Semester 2, Lecture 32 Mosiah 8–10 Ammon and Limhi The Record of Zeniff We are on chapter 8 of Mosiah, and it is absolutely staggering what’s in here. I’ve been missing everything all these years. We can’t stop for everything, but nevertheless it’s jammed in here. Remember that Ammon has come to King Limhi and has been invited to speak to the king. He’s in the palace now, and it follows strictly the proper palace procedure as you get it in all the epics, etc. Limhi makes an end of speaking. He tells his story, and then he invites the guest to speak and tell his story. This is a thing that is common in epics, of course. When Odysseus comes to the Phaeacians, the king of the Phaeacians is Alcinous, and he gives a long speech that runs through two books explaining how they happened to get there. Then he says to the guest as he is about to leave at the beginning of the ninth book, “Now tell us your story.” So Odysseus starts out, “I am Odysseus, the son of Laertes, noted throughout the world for my sufferings [everybody is watching my sufferings] and my fame goes to heaven. I live in Ithica [and he describes what a beautiful land it is]. It’s rough but it’s a good land, a nourisher of people rather than nothing.” The way it skips along is a marvelous thing, and then two lines later he tells how he lived for ten years with the nymph Calypso.