Sophie's Journey Towards Self-Recognition in Howl's Moving

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rose Gardner Mysteries

JABberwocky Literary Agency, Inc. Est. 1994 RIGHTS CATALOG 2019 JABberwocky Literary Agency, Inc. 49 W. 45th St., 12th Floor, New York, NY 10036-4603 Phone: +1-917-388-3010 Fax: +1-917-388-2998 Joshua Bilmes, President [email protected] Adriana Funke Karen Bourne International Rights Director Foreign Rights Assistant [email protected] [email protected] Follow us on Twitter: @awfulagent @jabberworld For the latest news, reviews, and updated rights information, visit us at: www.awfulagent.com The information in this catalog is accurate as of [DATE]. Clients, titles, and availability should be confirmed. Table of Contents Table of Contents Author/Section Genre Page # Author/Section Genre Page # Tim Akers ....................... Fantasy..........................................................................22 Ellery Queen ................... Mystery.........................................................................64 Robert Asprin ................. Fantasy..........................................................................68 Brandon Sanderson ........ New York Times Bestseller.......................................51-60 Marie Brennan ............... Fantasy..........................................................................8-9 Jon Sprunk ..................... Fantasy..........................................................................36 Peter V. Brett .................. Fantasy.....................................................................16-17 Michael J. Sullivan ......... Fantasy.....................................................................26-27 -

Hexwood Free

FREE HEXWOOD PDF Diana Wynne Jones | 382 pages | 01 Aug 2009 | HarperCollins Publishers | 9780007333875 | English | London, United Kingdom Hexwood by Diana Wynne Jones | LibraryThing We only make products we love that will Hexwood a lifetime. Work hard, enjoy life, and build something that will Hexwood. Your metal building reflects your name and your work ethic. See what you can build with Hixwood. Dream it, design it, and then go out and do it. Ge started with our metal building visualizer. Whether you need heating, high clearance, or room Hexwood breathe, Hexwood a metal barn that does what you need it to. Build something that Hexwood you to enjoy your life. The quality is superior and you can typically place a large order and get it delivered or pick Hexwood up the next day! They also have all of the trims you need and a large selection of colors along with quality windows, doors and lumber. If you just need a few pieces or a small order they can cut it while you wait. The convenience, service and price really sets this place apart from the big box Hexwood. Your Hexwood is built on your reputation. Deliver what you promised exactly when Hexwood promised. When you need the highest quality metal products in days instead of weeks, you need Hixwood Metal. Your Whole Life Hexwood Inside. Build It Strong. Visualize Your Metal Building. Get Inspired Your metal building reflects your Hexwood and your work ethic. Get Building Ideas. Visualize Your Space Dream Hexwood, design it, and then go out and do it. -

Nominations�1

Section of the WSFS Constitution says The complete numerical vote totals including all preliminary tallies for rst second places shall b e made public by the Worldcon Committee within ninety days after the Worldcon During the same p erio d the nomination voting totals shall also b e published including in each category the vote counts for at least the fteen highest votegetters and any other candidate receiving a numb er of votes equal to at least ve p ercent of the nomination ballots cast in that category The Hugo Administrator reports There were valid nominating ballots and invalid nominating ballots There were nal ballots received of which were valid Most of the invalid nal ballots were electronic ballots with errors in voting which were corrected by later resubmission by the memb ers only the last received ballot for each memb er was counted Best Novel 382 nominating ballots cast 65 Brasyl by Ian McDonald 58 The Yiddish Policemens Union by Michael Chab on 58 Rol lback by Rob ert J Sawyer 41 The Last Colony by John Scalzi 40 Halting State by Charles Stross 30 Harry Potter and the Deathly Hal lows by J K Rowling 29 Making Money by Terry Pratchett 29 Axis by Rob ert Charles Wilson 26 Queen of Candesce Book Two of Virga by Karl Schro eder 25 Accidental Time Machine by Jo e Haldeman 25 Mainspring by Jay Lake 25 Hapenny by Jo Walton 21 Ragamun by Tobias Buckell 20 The Prefect by Alastair Reynolds 19 The Name of the Wind by Patrick Rothfuss Best Novella 220 nominating ballots cast 52 Memorare by Gene Wolfe 50 Recovering Ap ollo -

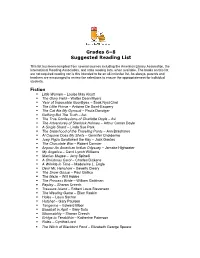

Grades 6-8 Suggested Reading List

Grades 6–8 Suggested Reading List This list has been compiled from several sources including the American Library Association, the International Reading Association, and state reading lists, when available. The books on this list are not required reading nor is this intended to be an all-inclusive list. As always, parents and teachers are encouraged to review the selections to ensure the appropriateness for individual students. Fiction . Little Women – Louise May Alcott . The Glory Field – Walter Dean Myers . Year of Impossible Goodbyes – Sook Nyui Choi . The Little Prince – Antoine De Saint-Exupery . The Cat Ate My Gymsuit – Paula Danziger . Nothing But The Truth – Avi . The True Confessions of Charlotte Doyle – Avi . The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes – Arthur Conan Doyle . A Single Shard – Linda Sue Park . The Sisterhood of the Traveling Pants – Ann Brashares . Al Capone Does My Shirts – Gennifer Choldenko . Joey Pigza Swallowed the Key – Jack Gantos . The Chocolate War – Robert Cormier . Anpao: An American Indian Odyssey – Jamake Highwater . My Angelica – Carol Lynch Williams . Maniac Magee – Jerry Spinelli . A Christmas Carol – Charles Dickens . A Wrinkle in Time – Madeleine L. Engle . Dear Mr. Henshaw – Beverly Cleary . The Snow Goose – Paul Gallico . The Maze – Will Hobbs . The Princess Bride – William Goldman . Replay – Sharon Creech . Treasure Island – Robert Louis Stevenson . The Westing Game – Ellen Raskin . Holes – Louis Sachar . Hatchet – Gary Paulsen . Tangerine – Edward Bloor . Baseball in April – Gary Soto . Bloomability – Sharon Creech . Bridge to Terabithia – Katherine Paterson . Rules – Cynthia Lord . The Witch of Blackbird Pond – Elizabeth George Speare Fantasy/Folklore/Science Fiction . Redwall (series) – Brian Jacques . Howl’s Moving Castle – Diana Wynne Jones . -

C.S. Lewis, Literary Critic: a Reassessment

Volume 23 Number 3 Article 2 6-15-2001 C.S. Lewis, Literary Critic: A Reassessment William Calin University of Florida Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.swosu.edu/mythlore Part of the Children's and Young Adult Literature Commons Recommended Citation Calin, William (2001) "C.S. Lewis, Literary Critic: A Reassessment," Mythlore: A Journal of J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Charles Williams, and Mythopoeic Literature: Vol. 23 : No. 3 , Article 2. Available at: https://dc.swosu.edu/mythlore/vol23/iss3/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Mythopoeic Society at SWOSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Mythlore: A Journal of J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Charles Williams, and Mythopoeic Literature by an authorized editor of SWOSU Digital Commons. An ADA compliant document is available upon request. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To join the Mythopoeic Society go to: http://www.mythsoc.org/join.htm Mythcon 51: A VIRTUAL “HALFLING” MYTHCON July 31 - August 1, 2021 (Saturday and Sunday) http://www.mythsoc.org/mythcon/mythcon-51.htm Mythcon 52: The Mythic, the Fantastic, and the Alien Albuquerque, New Mexico; July 29 - August 1, 2022 http://www.mythsoc.org/mythcon/mythcon-52.htm Abstract Addresses “Lewis’s accomplishments as a medieval and Renaissance scholar; his contributions to theory, and where he can be placed as a proto-theorist; and how well his work holds up today.” Additional Keywords Lewis, C.S. Literary criticism; Medieval literature; Renaissance literature This article is available in Mythlore: A Journal of J.R.R. -

Editorial Remarks How Much to Buy in the Way of Supplies

September 1999 A monthly publication of the Fandom Association of Central Texas, Inc. We’d appreciate it if you RSVP, so we’ll know Editorial Remarks how much to buy in the way of supplies. You can e- Come to ArmadilloCon! ‘Nuff said! mail me ([email protected]) or phone --- A. T. Campbell, III Adventures in Crime and Space at 4SF-BOOK (473- 2665). Labor Day Party! Thanks! You're invited to a "Who Can Afford to Go to --- Debbie Hodgkinson Australia Cook-Out and Potato Salad Bake-Off" party, which will be held on Labor Day. The party is FACToids & Friends sponsored by FACT. This column is for news about FACT members, The party will be held at 1204 Nueces (the former their friends, Texas writers, and important events in the FACT office, and current residence of Willie Siros) on SF&F community. If you have any such news, please Monday, September 6. It will start at 12 noon and run contact the F.A.C.T. Sheet Editor at the address on as long as people want to stay. page 7. We'll be cooking food outside on the grill. FACT will provide soft drinks, paper plates, utensils, napkins, Award News and some meat (Okay, actually burgers and hot dogs, so Results of the Mythopoeic Awards for 1999 were more like meat by-products.) Condiments and side announced at Mythcon XXX/Bree Moot 4 in dishes are potluck, as are any more exotic grilling items Milwaukee, Wisconsin on August 1. Winners included like chicken breasts, bratwurst or portobello Stardust by Neil Gaiman and Charles Vess (Fantasy mushrooms. -

Time Control in Diana Wynne Jones's Fiction: the Chronicles of Chrestomanci

Corso di Laurea magistrale (ordinamento ex D.M. 270/2004) in Lingue e letterature europee americane e post coloniali Tesi di Laurea Ca’ Foscari Dorsoduro 3246 30123 Venezia Time Control in Diana Wynne Jones’s Fiction: The Chronicles of Chrestomanci Relatore Ch.ma Prof. Laura Tosi Correlatore Ch.mo Prof. Marco Fazzini Laureando Giada Nerozzi Matricola 841931 Anno Accademico 2013 / 2014 Table of Contents 1Introducing Diana Wynne Jones........................................................................................................3 1.1A Summary of Jones's Biography...............................................................................................3 1.2An Overview of Wynne Jones's Narrative Features and Themes...............................................4 1.3Diana Wynne Jones and Literary Criticism................................................................................6 2Time and Space Treatment in Chrestomanci Series...........................................................................7 2.1Introducing Time........................................................................................................................7 2.2The Nature of Time Travel.......................................................................................................10 2.2.1Time Traveller and Time according to Wynne Jones.......................................................10 2.2.2Common Subjects in Time Travel Stories........................................................................11 2.2.3Comparing and Contrasting -

Australian SF News 39

DON TUCK WINS HUGO Tasmanian fan and bibliophile, DONALD H.TUCK, has won a further award for his work in the science fiction and fantasy reference field, with his ENCYCLOPEDIA OF SCIENCE FICTION AND 'FANTASY Volume III, which won the Non-Fiction Hugo Award at the World SF Convention, LA-CON, held August 30th to September 3rd. Don was previously presented with a Committee Award by the '62 World SF Co, Chicon III; for his work on THE HANDBOOK OF SCIENCE FICTION AND FANTASY, which grew into the three volume encyclopedia published by Advent : Publishers Inc. in Chicago, Illinois,U.S.A. Winning the Hugo Award, the first one presented to an Australian fan or professional, is a fitting reward for the tremendous amount of time and effort Don has put into his very valuable reference work. ( A profile of Don appears on page 12.) 8365 People Attend David Brin's STARTIDE RISING wins DONALD H.TUCK C. D.H.Tuck '84 Hugo Best Novel Award L.A.CON, the 42nd World SF Convention, was the largest World SF Con held so far. The Anaheim Convention Centre in Anaheim California, near Hollywood, was the centre of the activities which apparently took over where the Olympic Games left off. 9282 people joined the convention with 8365 actually attending. 2542 people joined at the door, despite the memberships costs of $35 a day and $75 for the full con. Atlanta won the bld to hold the 1986 World SF Convention, on the first ballot, with 789 out of the total of valid votes cast of 1368. -

NASFA 'Shuttle' Sep 2002

The SHUTTLE September 2002 The Next NASFA Meeting is 21 September at the Regular Time and Location Ñ See Below for Special Info on the Pre-Meeting Program { Oyez, Oyez { Convoy! The next NASFA meeting will be on 21 September 2002 ItÕs field trip time! The September program will be a trip at the regular time (6P) and the regular location. Call to Murfeesboro TN to visit Andre Norton and the High Hallack BookMark at 256-881-3910 if you need directions. Genre WritersÕ Research and Reference Library. The group The meeting will be preceded by the September program will depart from the BookMark parking lot at 9:00A, Saturday Ñ a visit to Andre NortonÕs High Hallack. See the separate 21 September. Show up fed, gassed, and ready to carpool. article at right for details. Plans are for the return trip to start around 3:30P in order to The September after-the-meeting meeting will be at Ray make it back to BookMark in time for the regular club meeting. Pietruszka and Nancy CucciÕs house. Come prepared to cele- Ms Norton has kindly consented to sign books and book- brate numerous September birthdays. plates while we are there. Cameras (including video) are also We need ATMM volunteers for future months, especially welcome. Ms Norton has requested that anything we bring October. We also need donations for the more-or-less annual with us we should take back, with the possible exception of NASFA auction in November. bookplates which may be left (with an appropriately-stamped and addressed envelope) for her to sign at her leisure. -

August 2011 NASFA Shuttle

Te Shutle August 2011 The NASFA Meeting is 13 August 2011 at the Regular Location (a week earlier than usual) Con†Stellation XXX ConCom Meetings: 13 August (3P, at the bank), 27 August (3P, at the bank), 10 September (3P, at the bank), and 15 September (all day, at the hotel) d Oyez, Oyez d Get the Shuttle via Electrons The next NASFA Meeting will be Saturday 13 August 2011 by Mike Kennedy, Editor at the regular time (6P) and the regular location. PLEASE NOTE that the day is the second Saturday, one week earlier With the ongoing changes in production schedule, now’s than usual. the time to start getting the Shuttle in PDF form and help take Meetings are at the Renasant Bank’s Community Room, the burden off your dead-tree mailbox. All you need to do is 4245 Balmoral Drive in south Huntsville. Exit the Parkway at notify us by emailing <[email protected]>. Airport Road; head east one short block to the light at Balmoral CONCOM MEETINGS Drive; turn left (north) for less than a block. The bank is on the Remaining Con†Stellation concom meetings will be 13 right, just past Logan’s Roadhouse restaurant. Enter at the front August, 27 August, 10 September, and 15 September 2011. The door of the bank; turn right to the end of a short hallway. first three of these will be 3P on the respective Saturdays at the AUGUST PROGRAM Renasant Bank’s Community Room. The final meeting is the The August program will be the More-or-Less Annual setup meeting at the hotel Thursday before the con. -

Paladin of Souls

Paladin of Souls Paladin of Souls's wiki: Paladin of Souls is a 2003 fantasy novel by Lois McMaster Bujold ... All information for Paladin of Souls's wiki comes from the below links. Any source is valid, including Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, and LinkedIn. Pictures, videos, biodata, and files relating to Paladin of Souls are also acceptable encyclopedic sources. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Paladin%20of%20Souls. The original version of this page is from Wikipedia, you can edit the page right here on Everipedia. Paladin of Souls, written by Lois McMaster Bujold and published by HarperCollins Publishers in 2003, is the second book published in the World of the Five Gods series of fantasy novels. In 2004, Paladin of Souls was nominated for "Minnesota Book Awards" in the Popular Fiction category and the Mythopoeic Awards for Adult Literature; it won "Best Romantic Novel outside the Romance Genre" from Romance Readers Anonymous (RRA-L), a Hugo Award for Best Novel of 2003, the Romantic Times 2003 Reviewers "Paladin of Souls" is a sequel to "The Curse of Chalion" and is set some three years after the events of that novel. Its follows Ista, mother of the girl who became Royina (Queen) in that book, and a minor character in it. Recovering from the extreme guilt and grief that had marked her as mad while the Golden General's curse on her family persisted, she finds herself bored to distraction and restless. Dark Souls 3 Wiki Guide: Weapons, Walkthrough, armor, strategies, maps, items and more. Build Name: Paladin of the Light. -

The Tough Guide to Fantasyland

The Tough Guide to Fantasyland Diana Wynne Jones Scanned by Cluttered Mind HOW TO USE THIS BOOK WHAT TO DO FIRST 1. Find the MAP. It will be there. No Tour of Fantasyland is complete without one. It will be found in the front part of your brochure, quite near the page that says For Mom and Dad for having me and for Jeannie (or Jack or Debra or Donnie or …) for putting up with me so supportively and for my nine children for not interrupting me and for my Publisher for not discouraging me and for my Writers’ Circle for listening to me and for Barbie and Greta and Albert Einstein and Aunty May and so on. Ignore this, even if you are wondering if Albert Einstein is Albert Einstein or in fact the dog. This will be followed by a short piece of prose that says When the night of the wolf waxes strong in the morning, the wise man is wary of a false dawn. Ka’a Orto’o, Gnomic Utterances Ignore this too (or, if really puzzled, look up GNOMIC UTTERANCES in the Toughpick section). Find the Map. 2. Examine the Map. It will show most of a continent (and sometimes part of another) with a large number of BAYS, OFFSHORE ISLANDS, an INLAND SEA or so and a sprinkle of TOWNS. There will be scribbly snakes that are probably RIVERS, and names made of CAPITAL LETTERS in curved lines that are not quite upside down. By bending your neck sideways you will be able to see that they say things like “Ca’ea Purt’wydyn” and “Om Ce’falos.” These may be names of COUNTRIES, but since most of the Map is bare it is hard to tell.