Download Booklet

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Atlanta Chamber Players, "Music of Norway"

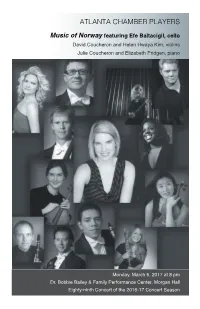

ATLANTA CHAMBER PLAYERS Music of Norway featuring Efe Baltacigil, cello David Coucheron and Helen Hwaya Kim, violins Julie Coucheron and Elizabeth Pridgen, piano Monday, March 6, 2017 at 8 pm Dr. Bobbie Bailey & Family Performance Center, Morgan Hall Eighty-ninth Concert of the 2016-17 Concert Season program JOHAN HALVORSEN (1864-1935) Concert Caprice on Norwegian Melodies David Coucheron and Helen Hwaya Kim, violins EDVARD GRIEG (1843-1907) Andante con moto in C minor for Piano Trio David Coucheron, violin Efe Baltacigil, cello Julie Coucheron, piano EDVARD GRIEG Violin Sonata No. 3 in C minor, Op. 45 Allegro molto ed appassionato Allegretto espressivo alla Romanza Allegro animato - Prestissimo David Coucheron, violin Julie Coucheron, piano INTERMISSION JOHAN HALVORSEN Passacaglia for Violin and Cello (after Handel) David Coucheron, violin Efe Baltacigil, cello EDVARD GRIEG Cello Sonata in A minor, Op. 36 Allegro agitato Andante molto tranquillo Allegro Efe Baltacigil, cello Elizabeth Pridgen, piano featured musician FE BALTACIGIL, Principal Cello of the Seattle Symphony since 2011, was previously Associate Principal Cello of The Philadelphia Orchestra. EThis season highlights include Brahms' Double Concerto with the Oslo Radio Symphony and Vivaldi's Double Concerto with the Seattle Symphony. Recent highlights include his Berlin Philharmonic debut under Sir Simon Rattle, performing Bottesini’s Duo Concertante with his brother Fora; performances of Tchaikovsky’s Variations on a Rococo Theme with the Bilkent & Seattle Symphonies; and Brahms’ Double Concerto with violinist Juliette Kang and the Curtis Symphony Orchestra. Baltacıgil performed a Brahms' Sextet with Itzhak Perlman, Midori, Yo-Yo Ma, Pinchas Zukerman and Jessica Thompson at Carnegie Hall, and has participated in Yo-Yo Ma’s Silk Road Project. -

Download Booklet

Edvard Grieg (1843 - 1907) Piano Music Vol. 1 Edvard Grieg, was born in Bergen, on the west coast of Norway. He showed a strong interest in music at very early age, and after encouragement by violinist and composer, Ole Bull (1810 - 1880), he was sent to the Conservatory inLeipzig at tile age of fifteentoreceivehismusiceducation. Atthe conservatoryhe receivedafundamental andsolid training, and through the city's active musicallife, he received impressions, and heard music, which would leave their stamp on him for the rest of his life, for better or for worse. Even though he severely criticized the conservatory, especiall;~ towards the end of his life, in reality he was recognised as a great talent, and one sees in his sketchbooks and practices from the Leipzig period that he had the freedom to experiment as well. He had no basis for criticizing the conservatory or his teachers for poor teaching or a lack of understanding. From Leipzig he travelled to Copenhagenwith a solid musical ballast and there he soon became known as a promising young composer. It was not long before he was under the influence of RikardNordraak,whose glowing enthusiasmand unshakeable that the key to a successful future for Norwegian music lay in nationalism, in the uniquely Norwegian, the music of the people folk-songs. Nordraak came to play a decisive role for Grieg's development as a composer. Nordraak's influence is most obvious in Grieg's Humoresker, Opirs 6, considered a breakthrough. In the autumn of 1866, Grieg settled down in Christiania (Oslo). In 1874 Norway's capital city was the centre for his activities. -

572095 Bk Tveitt 13/10/08 12:19 Page 12

572095 bk Tveitt 13/10/08 12:19 Page 12 WIND BAND CLASSICS Geirr TVEITT Sinfonia di Soffiatori • Sinfonietta di Soffiatori Selections from A Hundred Hardanger Tunes The Royal Norwegian Navy Band • Bjarte Engeset Geirr Tveitt on camel, Sahara Desert, 1953 Photo © Gyri and Haoko Tveitt 8.572095 12 572095 bk Tveitt 13/10/08 12:19 Page 2 Geirr TVEITT (1908-1981) Music for Wind Instruments Sinfonia di Soffiatori 16:01 Hundrad Hardingtonar 1 I. Moderato 4:43 (A Hundred Hardanger Tunes), 2 II. Alla marcia 3:56 3 III. Andante 7:22 Op. 151 (transcriptions by Stig Nordhagen) 4 Prinds Christian Frederiks Honnørmarch Suite No. 2: Femtan Fjelltonar (15 Mountain Songs) 5:45 (Prince Christian Fredrick’s @ No. 20: Med sterkt Øl te Fjells March of Honour) 3:19 (Bringing strong Ale into the Mountains) 1:23 # No. 23: Rjupo pao Folgafodne 5 Det gamle Kvernhuset (The Song of the Snow Grouse (The Old Mill on the Brook), on the Folgafodne Glacier) 3:04 Op. 204 3:03 $ No. 29: Fjedlmansjento upp i Lid (The Mountain Girl skiing Downhill) 1:18 6 Hymne til Fridomen Suite No. 4: Brudlaupssuiten (Hymn to Freedom) 3:05 (Wedding Suite) 6:30 % No. 47: Friarføter (Going a-wooing) 1:32 Sinfonietta di Soffiatori, Op. 203 12:40 ^ No. 52: Graot og Laott aot ain Baot 7 I. Intonazione d’autunno: Lento – (Tears and Laughter for a Boat) 1:37 Poco più mosso – Tempo I 4:00 & No. 60: Haringøl (Hardanger Ale) 3:20 8 II. Ricordi d’estate: Tempo moderato di springar 2:13 9 III. -

Edvard Grieg: Between Two Worlds Edvard Grieg: Between Two Worlds

EDVARD GRIEG: BETWEEN TWO WORLDS EDVARD GRIEG: BETWEEN TWO WORLDS By REBEKAH JORDAN A Thesis Submitted to the School of Graduate Studies in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts McMaster University © Copyright by Rebekah Jordan, April, 2003 MASTER OF ARTS (2003) 1vIc1vlaster University (1vIllSic <=riticisIll) HaIllilton, Ontario Title: Edvard Grieg: Between Two Worlds Author: Rebekah Jordan, B. 1vIus (EastIllan School of 1vIllSic) Sllpervisor: Dr. Hllgh Hartwell NUIllber of pages: v, 129 11 ABSTRACT Although Edvard Grieg is recognized primarily as a nationalist composer among a plethora of other nationalist composers, he is much more than that. While the inspiration for much of his music rests in the hills and fjords, the folk tales and legends, and the pastoral settings of his native Norway and his melodic lines and unique harmonies bring to the mind of the listener pictures of that land, to restrict Grieg's music to the realm of nationalism requires one to ignore its international character. In tracing the various transitions in the development of Grieg's compositional style, one can discern the influences of his early training in Bergen, his four years at the Leipzig Conservatory, and his friendship with Norwegian nationalists - all intricately blended with his own harmonic inventiveness -- to produce music which is uniquely Griegian. Though his music and his performances were received with acclaim in the major concert venues of Europe, Grieg continued to pursue international recognition to repudiate the criticism that he was only a composer of Norwegian music. In conclusion, this thesis demonstrates that the international influence of this so-called Norwegian maestro had a profound influence on many other composers and was instrumental in the development of Impressionist harmonies. -

Conference Program 2011

Grieg Conference in Copenhagen 11 to 13 August 2011 CONFERENCE PROGRAM 16.15: End of session Thursday 11 August: 17.00: Reception at Café Hammerich, Schæffergården, invited by the 10.30: Registration for the conference at Schæffergården Norwegian Ambassador 11.00: Opening of conference 19.30: Dinner at Schæffergården Opening speech: John Bergsagel, Copenhagen, Denmark Theme: “... an indefinable longing drove me towards Copenhagen" 21.00: “News about Grieg” . Moderator: Erling Dahl jr. , Bergen, Norway Per Dahl, Arvid Vollsnes, Siren Steen, Beryl Foster, Harald Herresthal, Erling 12.00: Lunch Dahl jr. 13.00: Afternoon session. Moderator: Øyvind Norheim, Oslo, Norway Friday 12 August: 13.00: Maria Eckhardt, Budapest, Hungary 08.00: Breakfast “Liszt and Grieg” 09.00: Morning session. Moderator: Beryl Foster, St.Albans, England 13.30: Jurjen Vis, Holland 09.00: Marianne Vahl, Oslo, Norway “Fuglsang as musical crossroad: paradise and paradise lost” - “’Solveig`s Song’ in light of Søren Kierkegaard” 14.00: Gregory Martin, Illinois, USA 09.30: Elisabeth Heil, Berlin, Germany “Lost Among Mountain and Fjord: Mythic Time in Edvard Grieg's Op. 44 “’Agnete’s Lullaby’ (N. W. Gade) and ‘Solveig’s Lullaby’ (E. Grieg) Song-cycle” – Two lullabies of the 19th century in comparison” 14.30: Coffee/tea 10.00: Camilla Hambro, Åbo, Finland “Edvard Grieg and a Mother’s Grief. Portrait with a lady in no man's land” 14.45: Constanze Leibinger, Hamburg, Germany “Edvard Grieg in Copenhagen – The influence of Niels W. Gade and 10.30: Coffee/tea J.P.E. Hartmann on his specific Norwegian folk tune.” 10.40: Jorma Lünenbürger, Berlin, Germany / Helsinki, Finland 15.15: Rune Andersen, Bjästa, Sweden "Grieg, Sibelius and the German Lied". -

Johan HALVORS Saraband Passacagl Concert C

8.572522 bk Halvorsen_Bruni_EU:8.572522 bk Halvorsen_Bruni_EU 16-08-2011 9:02 Pagina 1 Natalia Lomeiko Natalia Lomeiko launched her solo career at the age of seven with the Novosibirsk Philharmonic. A few years later she was invited to study at the Yehudi Menuhin School, hailed by Menuhin as ‘one of the most brilliant of our younger violinists’. After completing her studies at the Royal College and the Photo: Sasha Gusov Photo: Royal Academy of Music she won several prestigious international competi- Johan tions, including first prize in the Premio Paganini in Italy and Michael Hill in New Zealand. She has appeared with major orchestras around the world, including the St Petersburg Radio Symphony, Tokyo Royal Philharmonic, the New HALVORSEN Zealand Symphony, Auckland Philharmonia, Melbourne Symphony, Royal Philharmonic and many other orchestras. She has performed chamber music Also available with such renowned musicians as Gidon Kremer, Tabea Zimmermann, Dmitry Sarabande Sitkovetsky, Shlomo Mintz, Boris Pergamenschikov, Isabelle Faust and Yuri Bashmet. She has recorded for Dynamic, Foné and Trust Records with pianist Olga Sitkovetsky. In 2010 she was appointed Professor of Violin at the Royal College of Music in London. Passacaglia http://www.natalialomeiko.com http://www.lomeikozhislinduo.com Concert Caprice on Yuri Zhislin Norwegian Melodies Yuri Zhislin became the BBC Radio Two Young Musician of the Year in 1993 and has performed throughout Europe, America, Japan, Australia and New Zealand. He regularly appears both on the violin and the viola at festivals around the world. His chamber music partners have included María João Pires, Dmitry Sitkovetsky and Natalie Clein. -

3Johan Halvorsen

Johan Halvorsen 3 ORCHESTRAL WORKS Ragnhild Hemsing Hardanger fiddle Marianne Thorsen violin Bergen Philharmonic Orchestra Neeme Järvi Aftenposten / Press Association Images Johan Halvorsen, at home in Oslo, on the occasion of his seventieth birthday, 15 March 1934; the wintry scene depicted on the wall behind him is one of his own paintings Johan Halvorsen (1864 –1935) Orchestral Works, Volume 3 Symphony No. 3 26:12 in C major • in C-Dur • en ut majeur Edited by Jørn Fossheim 1 I Poco andante – Allegro moderato – Tranquillo – Poco più mosso – A tempo. Molto più mosso – Tranquillo – Un poco più mosso – Molto energico – Meno mosso – [A tempo] – Più allegro 9:23 2 II Andante – Allegro moderato – Tranquillo – Allegro molto – Andante. Tempo I – Adagio 7:58 3 III Finale. Allegro impetuoso – Poco meno mosso – Tranquillo – Stretto – Animando – Poco a poco meno mosso – Un poco tranquillo – Largamente – A tempo, più mosso – Tempo I – Poco meno mosso – Tranquillo – Poco meno mosso – Largamente – Andante – Allegro (Tempo I) – Stesso tempo – Più allegro 8:46 premiere recording 4 Sorte Svaner 4:54 (Black Swans) Andante – Più mosso – Un poco animato 3 5 Bryllupsmarsch, Op. 32 No. 1* 4:13 (Wedding March) for Violin Solo and Orchestra Til Arve Arvesen Allegretto marziale – Coda premiere recording 6 Rabnabryllaup uti Kraakjalund 3:59 (Wedding of Ravens in the Grove of the Crows) Norwegian Folk Melody Arranged for String Orchestra Andante Fossegrimen, Op. 21† 29:49 Dramatic Suite for Orchestra Deres Majestæter Kong Håkon VII. og Dronning Maud i dybeste ærbødighed tilegnet Melina Mandozzi violin 7 I Fossegrimen. Allegro moderato – Meno allegro – Più lento – Più vivo – Più allegro – Un poco più allegro – Tempo I, ma un poco meno mosso – Allegro molto 6:29 8 II Huldremøyarnes Dans. -

Persecution, Collaboration, Resistance

Münsteraner Schriften zur zeitgenössischen Musik 5 Ina Rupprecht (ed.) Persecution, Collaboration, Resistance Music in the ›Reichskommissariat Norwegen‹ (1940–45) Münsteraner Schrift en zur zeitgenössischen Musik Edited by Michael Custodis Volume 5 Ina Rupprecht (ed.) Persecution, Collaboration, Resistance Music in the ‘Reichskommissariat Norwegen’ (1940–45) Waxmann 2020 Münster x New York The publication was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft , the Grieg Research Centre and the Westfälische Wilhelms-Universität Münster as well as the Open Access Publication Fund of the University of Münster. Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek Th e Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografi e; detailed bibliographic data are available in the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de Münsteraner Schrift en zur zeitgenössischen Musik, Volume 5 Print-ISBN 978-3-8309-4130-9 E-Book-ISBN 978-3-8309-9130-4 DOI: https://doi.org/10.31244/9783830991304 CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 Waxmann Verlag GmbH, 2020 Steinfurter Straße 555, 48159 Münster www.waxmann.com [email protected] Cover design: Pleßmann Design, Ascheberg Cover pictures: © Hjemmefrontarkivet, HA HHI DK DECA_0001_44, saddle of sources regarding the Norwegian resistance; Riksarkivet, Oslo, RA/RAFA-3309/U 39A/ 4/4-7, img 197, Atlantic Presse- bilderdienst 12. February 1942: Th e newly appointed Norwegian NS prime minister Vidkun Quisling (on the right) and Reichskomissar Josef Terboven (on the left ) walking along the front of an honorary -

Norway – Music and Musical Life

Norway2BOOK.book Page 273 Thursday, August 21, 2008 11:35 PM Chapter 18 Norway – Music and Musical Life Chapter 18 Norway – Music and Musical Life By Arvid Vollsnes Through all the centuries of documented Norwegian music it has been obvi- ous that there were strong connections to European cultural life. But from the 14th to the 19th century Norway was considered by other Europeans to be remote and belonging to the backwaters of Europe. Some daring travel- ers came in the Romantic era, and one of them wrote: The fantastic pillars and arches of fairy folk-lore may still be descried in the deep secluded glens of Thelemarken, undefaced with stucco, not propped by unsightly modern buttress. The harp of popular minstrelsy – though it hangs mouldering and mildewed with infrequency of use, its strings unbraced for want of cunning hands that can tune and strike them as the Scalds of Eld – may still now and then be heard sending forth its simple music. Sometimes this assumes the shape of a soothing lullaby to the sleep- ing babe, or an artless ballad of love-lorn swains, or an arch satire on rustic doings and foibles. Sometimes it swells into a symphony descriptive of the descent of Odin; or, in somewhat less Pindaric, and more Dibdin strain, it recounts the deeds of the rollicking, death-despising Vikings; while, anon, its numbers rise and fall with mysterious cadence as it strives to give a local habitation and a name to the dimly seen forms and antic pranks of the hol- low-backed Huldra crew.” (From The Oxonian in Thelemarken, or Notes of Travel in South-Western Norway in the Summers of 1856 and 1857, written by Frederick Metcalfe, Lincoln College, Oxford.) This was a typical Romantic way of describing a foreign culture. -

Marco Polo – the Label of Discovery

Marco Polo – The Label of Discovery Doubt was expressed by his contemporaries as to the truth of Marco Polo’s account of his years at the court of the Mongol Emperor of China. For some he was known as a man of a million lies, and one recent scholar has plausibly suggested that the account of his travels was a fiction inspired by a family dispute. There is, though, no doubt about the musical treasures daily uncovered by the Marco Polo record label. To paraphrase Marco Polo himself: All people who wish to know the varied music of men and the peculiarities of the various regions of the world, buy these recordings and listen with open ears. The original concept of the Marco Polo label was to bring to listeners unknown compositions by well-known composers. There was, at the same time, an ambition to bring the East to the West. Since then there have been many changes in public taste and in the availability of recorded music. Composers once little known are now easily available in recordings. Marco Polo, in consequence, has set out on further adventures of discovery and exploration. One early field of exploration lay in the work of later Romantic composers, whose turn has now come again. In addition to pioneering recordings of the operas of Franz Schreker, Der ferne Klang (The Distant Sound), Die Gezeichneten (The Marked Ones) and Die Flammen (The Flames), were three operas by Wagner’s son, Siegfried. Der Bärenhäuter (The Man in the Bear’s Skin), Banadietrich and Schwarzschwanenreich (The Kingdom of the Black Swan) explore a mysterious medieval world of German legend in a musical language more akin to that of his teacher Humperdinck than to that of his father. -

Program Conference 2007

THE INTERNATIONAL GRIEG SOCIETY – IGS CONFERENCE Bergen, Norway 30 May - 2 June 2007 Theme: ”BEYOND GRIEG – Edvard Grieg and his Diverse Influences on Music of the 20th and 21st Centuries”. PROGRAM Wednesday 30 May: Bergen Art Museum - Lysverket, ”Tårnsalen”, Rasmus Meyers Allé 9 12.00 -14.00: Registration 14.00: Opening of the Conference with the Mayor of Bergen and the Leader of IGS 14.10: Opening speech by President of the IGS, Arvid Vollsnes (Norway) 14.30: Keynote speakers: Malcolm Gillies and David Pear (Australia): ”Percy Grainger: Grieg’s Interpreter and Propagator” 15.15 – 15.30: Coffee/tea/snacks 15.30: Grieg’s Contemporary Relations and Influences Jorma Daniel Lünenbürger (Germany): “Grieg as the ‘Father of Finnish Music’? Notes on Grieg and Sibelius with Special Attention to the F major Violin Sonatas” Ohran Noh (Canada): “Edvard Grieg’s Influence on American Music: The Case of the Piano Concertos in A minor from the Pen of Edvard Grieg and Edward MacDowell” Helena Kopchick (USA): “Coding the Supernatural ‘other’ in Three Musical Settings of Henrik Ibsen’s Spillemænd” Asbjørn Ø. Eriksen (Norway): ”Griegian Fingerprints in the Music of Frederick Delius (1862-1934)” Yvonne Wasserloos (Germany): “Hearing through Eyes, Seeing through Ears". Music, Nation and Landscapes within the Works of Niels W.Gade, Edvard Grieg and Carl Nielsen” 17.30: Presentation of Grieg 07 17.45: End of Session 9.30: Bergen International Festival arranges a Grieg-galla in the Grieg Hall. Tickets are reserved for the conference participants. Thursday 31 May: The Grieg Academy, University of Bergen, Gunnar Sævigs Sal, Nina Griegs Allé. -

Nils Henrik Asheim Organ of Stavanger Concert Hall Edvard Grieg–Ballade Geirr Tveitt–Hundrad Hardingtonar

EDVARD GRIEG–BALLADE GEIRR TVEITT–HUNDRAD HARDINGTONAR NILS HENRIK ASHEIM ORGAN OF STAVANGER CONCERT HALL GRIEG & TVEITT i dette med mine spillende fingre. for en samling som både inneholder som primært er hans egen TI L ORGELET Transkripsjon og innspilling blir folketoner, egne komposisjoner og komposisjon, sa Tveitt en gang i et personlige statements fra oversetter hybrider, Geirr Tveitts personlige radioprogram: «...hinsides menneskelig Å dele musikk og utøver. versjon av folkekunsten. oppfatning og evne, dypt nede fra Før i tida transkriberte man De hardangerske folketonene underbevisstheten, symbolisert ved orkestermusikk til orgel eller piano Et orgel, men i en konsertsal er ofte korte og upretensiøse. På én de underjordiskes musikk, kommer de for at den skulle nå ut til de tusen Denne plata er den første fra orgelet i linje eller to kommenterer de konkrete virkelige toner, sannhetens toner...» hjem. Nå er situasjonen en annen: Stavanger konserthus. Jeg har ønsket hendelser i dagliglivet med ironi og Vi har tilgang på alle verk i form av å finne musikk som kler instrumentets brodd. Hver for seg bygger Tveitts Stedet og det private innspillinger. Hvorfor tiltrekkes vi egenart. Dette orgelet har en mørk, Hardingtonar på ganske enkelt Flere av Hardingtonane er knyttet likevel av å skape nye versjoner? varm klang. Akustikken i Fartein Valen- materiale, men til sammen danner de til hjemsted og berører det private Kanskje det er fordi vi ikke liker salen gjør den levende og organisk. en kompleks og sammensatt helhet, et området og familien. Vélkomne med tanken på at det skal finnes en endelig At vi er i en konsertsal og ikke en fasettert selvportrett.