Caretaking Democracy Political Process in Bangladesh, 2006-08

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bangladesh Country Report BTI 2008

BTI 2008 | Bangladesh Country Report Status Index 1-10 5.53 # 68 of 125 Democracy 1-10 5.95 # 66 of 125 Ê Market Economy 1-10 5.11 # 74 of 125 Ä Management Index 1-10 4.14 # 93 of 125 scale: 1 (lowest) to 10 (highest) score rank trend This report is part of the Bertelsmann Transformation Index (BTI) 2008. The BTI is a global ranking of transition processes in which the state of democracy and market economic systems as well as the quality of political management in 125 transformation and developing countries are evaluated. The BTI is a joint project of the Bertelsmann Stiftung and the Center for Applied Policy Research (C•A•P) at Munich University. More on the BTI at http://www.bertelsmann-transformation-index.de/ Please cite as follows: Bertelsmann Stiftung, BTI 2008 — Bangladesh Country Report. Gütersloh: Bertelsmann Stiftung, 2007. © 2007 Bertelsmann Stiftung, Gütersloh BTI 2008 | Bangladesh 2 Key Indicators Population mn. 141.8 HDI 0.53 GDP p.c. $ 1,827 Pop. growth1 % p.a. 1.9 HDI rank of 177 137 Gini Index 33.4 Life expectancy years 64 UN Education Index 0.46 Poverty3 % 84.0 Urban population % 25.1 Gender equality2 0.37 Aid per capita $ 9.4 Sources: UNDP, Human Development Report 2006 | The World Bank, World Development Indicators 2007 | OECD Development Assistance Committee 2006. Footnotes: (1) Average annual growth rate 1990-2005. (2) Gender Empowerment Measure (GEM). (3) Percentage of population living on less than $2 a day. Executive Summary The situation in Bangladesh during the review period was marked by a sharp contrast between the positive macroeconomic development and negative political developments. -

Bangladesh and Bangladesh-U.S. Relations

Bangladesh and Bangladesh-U.S. Relations Updated October 17, 2017 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov R44094 Bangladesh and Bangladesh-U.S. Relations Summary Bangladesh (the former East Pakistan) is a Muslim-majority nation in South Asia, bordering India, Burma, and the Bay of Bengal. It is the world’s eighth most populous country with nearly 160 million people living in a land area about the size of Iowa. It is an economically poor nation, and it suffers from high levels of corruption. In recent years, its democratic system has faced an array of challenges, including political violence, weak governance, poverty, demographic and environmental strains, and Islamist militancy. The United States has a long-standing and supportive relationship with Bangladesh, and it views Bangladesh as a moderate voice in the Islamic world. In relations with Dhaka, Bangladesh’s capital, the U.S. government, along with Members of Congress, has focused on a range of issues, especially those relating to economic development, humanitarian concerns, labor rights, human rights, good governance, and counterterrorism. The Awami League (AL) and the Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP) dominate Bangladeshi politics. When in opposition, both parties have at times sought to regain control of the government through demonstrations, labor strikes, and transport blockades, as well as at the ballot box. Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina has been in office since 2009, and her AL party was reelected in January 2014 with an overwhelming majority in parliament—in part because the BNP, led by Khaleda Zia, boycotted the vote. The BNP has called for new elections, and in recent years, it has organized a series of blockades and strikes. -

Party System in Bangladesh

SUBJECT: POLITICAL SCIENCE VI COURSE: BA LLB SEMESTER V (NON-CBCS) TEACHER: MS. DEEPIKA GAHATRAJ MODULE I, BANGLADESH PARTY SYSTEM Political Historical Background of Bangladesh: Bangladesh is a densely populated country in South Asia. Roughly 60% of its population lives under the poverty level. Its geography is dominated by its low-lying riparian aspect and its population is largely Muslim. History of the role of the political parties to established good governance is rich in Bangladesh, example 1947, 1971, and 1990. Anti-colonial movements against British rule, Pakistani exploitation, militant anarchy. However, these are the single side of the reality. In recent times the ideological conflict between ruling party and the party in opposition is leading the country toward an unwanted situation which will ultimately eliminate good governance segment by segment by poisoning slowly. Most disturbing fact is that political leaders are unwilling to recognize how their actions are threatening the very fabric of democracy. The failure of the political parties to negotiate in keeping national interest threatens the future of democracy in Bangladesh. No doubt, nothing has changed since these remarks were made. In the years since independence, Bangladesh has established a reputation as a largely moderate and democratic majority Muslim country. But this status has been under threat for series of political violence, weak governance, poverty, corruption, and religious militancy. In more recent years religious and anti-religious thoughts have been vigorously pursued by the government. The Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP) is led by former Prime Minister Khaleda Zia and the Awami League (AL) is led by current Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina who traditionally have been dominating politics in Bangladesh. -

Bangladesh: Back to the Future

BANGLADESH: BACK TO THE FUTURE Asia Report N°226 – 13 June 2012 TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ...................................................................................................... i I. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................. 1 II. THE LEGACY OF THE CARETAKER GOVERNMENT ......................................... 2 III. SHATTERED HOPES UNDER THE AWAMI LEAGUE .......................................... 4 A. THE FIFTEENTH AMENDMENT ...................................................................................................... 4 B. CRACKDOWN ON THE OPPOSITION ............................................................................................... 5 C. POLITICISATION OF THE SECURITY FORCES AND JUDICIARY ........................................................ 6 D. WAR CRIMES TRIALS ................................................................................................................... 7 E. CORRUPTION ................................................................................................................................ 8 F. THE AWAMI LEAGUE IN POWER ................................................................................................... 8 IV. THE OTHER PARTIES ................................................................................................... 9 A. THE BNP .................................................................................................................................... -

Bangladesh Gazette

Registered No. DA-1 Bangladesh Gazette Government of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh Additional issue Published by the Authority Monday, September 24, 2012 Bangladesh National Parliament Dhaka, 24 September, 2012/09 Ashwin, 1419 Following Act is adopted by the Parliament and got consent of the President on 24 September, 2012/09 Ashwin, 1419 and the Act is hereby going to be published for information of the public:- Act No. 34 of the year 2012 The Act enacted to make the activities about disaster management coordinated, object oriented and strengthened and to formulate rules to build up infrastructure of effective disaster management to fight all types of disaster Whereas, it is expedient and necessary to mitigate overall disaster, conduct post disaster rescue and rehabilitation program with more skill, provide emergency humanitarian aid to vulnerable community by bringing the harmful effect of disaster to a tolerable level through adopting disaster risk reduction programs and to enact rules to create effective disaster management infrastructure to fight disaster to make the activities of concerned public and private organizations more coordinated, object oriented and strengthened to face the disasters; Therefore, the following Act is enacted hereby: -- ------------------------------------------------------------ (173441) Value : Tk. 30.00 173442 Bangladesh Gazette, additional issue, September 24, 2012 Chapter one Preamble 1. Short Title and Commencement.-- (1) This Act may be called as Disaster Management Act. (2) It would come in -

Power, Corruption, Social Exclusion, and Climate Change in Bangladesh

Governance Matters: Power, Corruption, Social Exclusion, and Climate Change in Bangladesh Item Type text; Electronic Dissertation Authors Rahman, Md Ashiqur Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 29/09/2021 09:41:13 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/581306 GOVERNANCE MATTERS: POWER, CORRUPTION, SOCIAL EXCLUSION, AND CLIMATE CHANGE IN BANGLADESH by Md. Ashiqur Rahman CopyriGht © Md. Ashiqur Rahman 2015 A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the SCHOOL OF ANTHROPOLOGY In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the DeGree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY In the Graduate ColleGe THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2015 THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA GRADUATE COLLEGE As members of the Dissertation Committee, we certify that we haVe read the dissertation prepared by Md. Ashiqur Rahman, titled GOVERNANCE MATTERS: POWER, CORRUPTION, SOCIAL EXCLUSION, AND CLIMATE CHANGE IN BANGLADESH and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the dissertation requirement for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy. ________________________________________Date: 07/10/2015 Timothy J Finan ________________________________________Date: 07/10/2015 James B GreenberG ________________________________________Date: 07/10/2015 Mamadou A Baro ________________________________________Date: 07/10/2015 Saleemul Huq Final approval and acceptance of this dissertation is contingent upon the candidate’s submission of the final copies of the dissertation to the Graduate College. I hereby certify that I haVe read this dissertation prepared under my direction and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the dissertation requirement. -

Jatiya Sangsad: the Parliament of Bangladesh

Jatiya Sangsad: The Parliament of Bangladesh By Nizam Ahmed The Jatiya Sangsad, as the Parliament is called in Bangladesh, predates the independence of the country in 1971. Its precursor, the Legislative Council of Bengal, was established during the British colonial rule in 1861 when only a few countries outside Europe and North America could claim to have established such an institution. But the Parliament did not have any steady growth until recently. Several structural, procedural and political constraints made the Parliament seriously disadvantaged vis-à-vis other sources of power, particularly the government, during the colonial days and nearly a quarter century of Pakistani neo-colonial rule (1947-71). Since independence, Bangladesh has experimented with different types of government – multiparty parliamentary system patterned after the Westminster model (1971-74), one-party presidential system (1975), and multi-party presidential system (1978-82; 1986-1990). For eight years between 1975 and 1990, the country remained under absolute military rule. In September 1991 the multi-party parliamentary system was restored. Since then, Bangladesh has officially remained a parliamentary democracy. Ten parliaments have been elected over the last four decades (1973-2014), although only a few have been able to complete their five-year tenure. Among the Parliaments, those elected since the early 1990s have survived longer; the 1 only exception was the sixth Parliament (1996) which met for only four days. The ‘recent’ parliaments, which have enjoyed greater legitimacy than their predecessors, have also undertaken several measures to modernize procedures to improve their capacity to affect the policy outcome as well as to make the government behave. -

Download File

Cover and section photo credits Cover Photo: “Untitled” by Nurus Salam is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0 (Shangu River, Bangladesh). https://www.flickr.com/photos/nurus_salam_aupi/5636388590 Country Overview Section Photo: “village boy rowing a boat” by Nasir Khan is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0. https://www.flickr.com/photos/nasir-khan/7905217802 Disaster Overview Section Photo: Bangladesh firefighters train on collaborative search and rescue operations with the Bangladesh Armed Forces Division at the 2013 Pacific Resilience Disaster Response Exercise & Exchange (DREE) in Dhaka, Bangladesh. https://www.flickr.com/photos/oregonmildep/11856561605 Organizational Structure for Disaster Management Section Photo: “IMG_1313” Oregon National Guard. State Partnership Program. Photo by CW3 Devin Wickenhagen is licensed under CC BY 2.0. https://www.flickr.com/photos/oregonmildep/14573679193 Infrastructure Section Photo: “River scene in Bangladesh, 2008 Photo: AusAID” Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT) is licensed under CC BY 2.0. https://www.flickr.com/photos/dfataustralianaid/10717349593/ Health Section Photo: “Arsenic safe village-woman at handpump” by REACH: Improving water security for the poor is licensed under CC BY 2.0. https://www.flickr.com/photos/reachwater/18269723728 Women, Peace, and Security Section Photo: “Taroni’s wife, Baby Shikari” USAID Bangladesh photo by Morgana Wingard. https://www.flickr.com/photos/usaid_bangladesh/27833327015/ Conclusion Section Photo: “A fisherman and the crow” by Adnan Islam is licensed under CC BY 2.0. Dhaka, Bangladesh. https://www.flickr.com/photos/adnanbangladesh/543688968 Appendices Section Photo: “Water Works Road” in Dhaka, Bangladesh by David Stanley is licensed under CC BY 2.0. -

Download Article

Unpacking Bangladesh’s 2014 Elections A Clash of the “Warring Begums” Pavlo Ignatiev This work analyses events in the political life of Bangladesh after mili- tary Âle. It focuses on the rise of the leaders of two influential parties – the Awami League and the Bangladesh Nationalist Party – and the rea- sons for their animosity towards one another. I argue that both these political forces usually abide by a “winner-takes-all” principle and they are firmly against cooperation for the sake of the country. The polar- isation of the political field, combined with natural calamities and a crisis in the textile industry, is propelling Bangladesh into an uncertain future. Keywords: Bangladesh, India, political parties, elections, textile industry strikes Introduction: An Environmental and Economic Profile of Bangladesh Bangladesh is a medium-sized country wedged between India and My- anmar within Asia’s largest delta, the Ganges-Brahmaputra. More than 4095 km of Bangladesh’s frontiers are shared with India and 350 km with Myanmar. Seven north-eastern Indian states – better known as the Seven Sisters – and their predominantly tribal and Christian popu- lations of 42 million, can only access Bengal Bay through Myanmar or Bangladesh. Moreover, India controls 54 Bangladeshi rivers and uses their water for its own industrial and agricultural needs. The long and ill-protected border also provides ample opportunities for the smug- Scan this arti- gling of cows, food and consumer goods. In 2013, some 3.2 million cle onto your Bangladeshi citizens resided in India on a permanent basis, sending mobile device home considerable remittances.1 This, combined with the explosive 40 issue of the presence of illegal Bangladeshi immigrants in eastern and north-eastern Indian states, has made ofcial relations with Delhi a topic of extraordinary political importance. -

BANGLADESH COUNTRY of ORIGIN INFORMATION (COI) REPORT COI Service

BANGLADESH COUNTRY OF ORIGIN INFORMATION (COI) REPORT COI Service Date 30 September 2012 BANGLADESH 30 SEPTEMBER 2012 Contents Go to End Preface REPORTS ON BANGLADESH PUBLISHED OR FIRST ACCESSED BETWEEN 31 AUGUST AND 30 SEPTEMBER 2012 Paragraphs Background Information 1. GEOGRAPHY ................................................................................................................... 1.01 Public holidays ................................................................................................... 1.06 Maps of Bangladesh ............................................................................................. 1.07 Other maps of Bangladesh ................................................................................. 1.07 2. ECONOMY ....................................................................................................................... 2.01 3. HISTORY ......................................................................................................................... 3.01 Pre-independence: 1947- 1971 ............................................................................ 3.01 Post-independence: 1972 - April 2010 .............................................................. 3.02 Government of Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, 1972-75 ............................................. 3.02 Government of Ziaur Rahman, 1975-81 ............................................................. 3.03 Government of Hussain Mohammed Ershad, 1982-90 ...................................... 3.04 Government of Khaleda Zia, -

Pre-Feasibility Study on Improvement of Grid Operation by Introducing Secure Power System Operation Technology in Asia

FY2018 Study on overseas business development of Japanese high-quality energy infrastructure Pre-Feasibility study on improvement of grid operation by introducing secure power system operation technology in Asia Final Report March 2019 Prepared for: Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry Prerared by: TEPCO IEC, Inc. Bangladesh Contents Contents .................................................................................................................................................................................. i Abbreviation ........................................................................................................................................................................ iii 1 Project Description ...................................................................................................................................................1-1 1.1 Project Objective...........................................................................................................................................1-1 1.2 Project Description.......................................................................................................................................1-1 1.3 Project Implementation Structure ..........................................................................................................1-3 1.4 Project Implementation Schedule ..........................................................................................................1-3 2 Current Status of the Country Surveyed ..........................................................................................................2-1 -

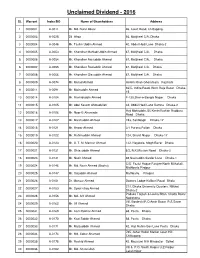

Unclaimed Divident

Unclaimed Dividend - 2016 SL Warrant Index/BO Name of Shareholders Address 1 0000001 A-0011 Mr. Md. Nurul Absar 46, Court Road, Chittagong. 2 0000003 A-0025 Dil Afroz 66, Motijheel C/A, Dhaka 3 0000004 A-0048 Mr. Taslim Uddin Ahmed 40, Abdul Hadi Lane Dhaka-2 4 0000005 A-0053 Mr. Khondker Mahtab Uddin Ahmed 67, Motijheel C/A. Dhaka 5 0000006 A-0054 Mr. Khondker Raisuddin Ahmed 67, Motijheel C/A. Dhaka 6 0000007 A-0055 Mr. Khondker Raziuddin Ahmed 67, Motijheel C/A. Dhaka 7 0000008 A-0056 Mr. Khondker Giasuddin Ahmed 67, Motijheel C/A. Dhaka 8 0000009 A-0074 Mr. Murad Ahmed Hetem Khan Ghoramara Rajshahi 66/C, Indira Road, West Raja Bazar Dhaka- 9 0000011 A-0091 Mr. Moinuddin Ahmed 15 10 0000014 A-0104 Mr. Rashiduddin Ahmed F-130,Sher-e-Bangla Nagar Dhaka 11 0000015 A-0105 Mr. Abul Kasem Ahmadullah 34, Abdul Hadi Lane Ramna Dhaka-2 Haji Mohiuddin, 56 KiminiVushan Rudduru 12 0000016 A-0106 Mr. Noor-E-Ahameda Road Dhaka 13 0000017 A-0107 Mr. Masihuddin Ahmed 193, Santibagh Dhaka-17 14 0000018 A-0121 Mr. Anwar Ahmed 3/1 Purana Paltan Dhaka 15 0000019 A-0122 Mr. Rahimuddin Ahmed 124, Shanti Nagar Dhaka-17 16 0000020 A-0123 Mr. A. T. M. Mansur Ahmed 132, Nayatola, Mogh Bazar Dhaka 17 0000021 A-0131 Mr. Ghiasuddin Ahmed 8/2, R.K.Mission Road Dhaka-3 18 0000023 A-0141 Mr. Nazir Ahmed 48,Nasiruddin Sardar Lane Dhaka-1 C/O. Fazlul Haque Farajee North Mithakali, 19 0000024 A-0146 Mr.