A History of Unit Stabilization

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MILITARY INTELLIGENCE PB 34-04-4 Volume 30 Number 4 October-December 2004 STAFF: FEATURES Commanding General Major General Barbara G

MILITARY INTELLIGENCE PB 34-04-4 Volume 30 Number 4 October-December 2004 STAFF: FEATURES Commanding General Major General Barbara G. Fast 8 Tactical Intelligence Shortcomings in Iraq: Restructuring Deputy Commanding General Battalion Intelligence to Win Brigadier General Brian A. Keller by Major Bill Benson and Captain Sean Nowlan Deputy Commandant for Futures Jerry V. Proctor Director of Training Development 16 Measuring Anti-U.S. Sentiment and Conducting Media and Support Analysis in The Republic of Korea (ROK) Colonel Eileen M. Ahearn by Major Daniel S. Burgess Deputy Director/Dean of Training Development and Support 24 Army’s MI School Faces TRADOC Accreditation Russell W. Watson, Ph.D. by John J. Craig Chief, Doctrine Division Stephen B. Leeder 25 USAIC&FH Observations, Insights, and Lessons Learned Managing Editor (OIL) Process Sterilla A. Smith by Dee K. Barnett, Command Sergeant Major (Retired) Editor Elizabeth A. McGovern 27 Brigade Combat Team (BCT) Intelligence Operations Design Director SSG Sharon K. Nieto by Michael A. Brake Associate Design Director and Administration 29 North Korean Special Operations Forces: 1996 Kangnung Specialist Angiene L. Myers Submarine Infiltration Cover Photographs: by Major Harry P. Dies, Jr. Courtesy of the U.S. Army Cover Design: 35 Deconstructing The Theory of 4th Generation Warfare Specialist Angiene L. Myers by Del Stewart, Chief Warrant Officer Three (Retired) Purpose: The U.S. Army Intelli- gence Center and Fort Huachuca (USAIC&FH) publishes the Military DEPARTMENTS Intelligence Professional Bulle- tin quarterly under provisions of AR 2 Always Out Front 58 Language Action 25-30. MIPB disseminates mate- rial designed to enhance individu- 3 CSM Forum 60 Professional Reader als’ knowledge of past, current, and emerging concepts, doctrine, materi- 4 Technical Perspective 62 MIPB 2004 Index al, training, and professional develop- ments in the MI Corps. -

Volu Is Here to Stay!

AUGUST 2020 edited by: Capt Joshua M. Nussbaum, PAWG Assistant Director of Professional Development VolU is Here to Stay! Inside This Issue 2 From the Editor 2 PD Track Advancements 2 Welcome Our New PDOs! 3 Cohort Request 4 VolU Uploads 5 Self-Study vs. Cohorts 8 Becoming an Instructor 9 2020 Course Grads 10 2020 PAWG Conference 11 Cadet Programs Waiver 11 Grandfather Clause 12 Motivation 12 Submissions 12 Contact Us!! 2 From the Editor When was the last time you tried something new? I remember one of my high school yearbooks had the motif of “something old, something new; something black, something blue.” Our school’s colors were pitch black and turquoise blue. Everything we do, everything we see, and everything we like- was once something new. The first time you ate at your favorite restaurant? You had never tried it before. The car you own? You had to take a first drive at some point. Your favorite TV show? It was new some time. Your career? I’m sure there was anxiety in the beginning. Our decision to join Civil Air Patrol was once something new, as well! When we each began this journey, we all had something to spark our interest. Whether a child joined, we joined for the aerospace education, or we wanted to fly, we wanted to learn how to complete missing person searches- something intrigued us and we kept coming back. Volunteer University, our new online learning system, is up and running. There are still minor edits being made, but the overarching product is here to stay. -

2Nd INFANTRY REGIMENT

2nd INFANTRY REGIMENT 1110 pages (approximate) Boxes 1243-1244 The 2nd Infantry Regiment was a component part of the 5th Infantry Division. This Division was activated in 1939 but did not enter combat until it landed on Utah Beach, Normandy, three days after D-Day. For the remainder of the war in Europe the Division participated in numerous operations and engagements of the Normandy, Northern France, Rhineland, Ardennes-Alsace and Central Europe campaigns. The records of the 2nd Infantry Regiment consist mostly of after action reports and journals which provide detailed accounts of the operations of the Regiment from July 1944 to May 1945. The records also contain correspondence on the early history of the Regiment prior to World War II and to its training activities in the United States prior to entering combat. Of particular importance is a file on the work of the Regiment while serving on occupation duty in Iceland in 1942. CONTAINER LIST Box No. Folder Title 1243 2nd Infantry Regiment Unit Histories January 1943-June 1944 2nd Infantry Regiment Unit Histories, July-October 1944 2nd Infantry Regiment Histories, July 1944- December 1945 2nd Infantry Regiment After Action Reports, July-September 1944 2nd Infantry Regiment After Action Reports, October-December 1944 2nd Infantry Regiment After Action Reports, January-May 1945 2nd Infantry Regiment Casualty List, 1944-1945 2nd Infantry Regiment Unit Journal, 1945 2nd Infantry Regiment Narrative History, October 1944-May 1945 2nd Infantry Regiment History Correspondence, 1934-1936 2nd Infantry -

Leadership Stability in Army Reserve Component Units

CHILDREN AND FAMILIES The RAND Corporation is a nonprofit institution that helps improve policy and EDUCATION AND THE ARTS decisionmaking through research and analysis. ENERGY AND ENVIRONMENT HEALTH AND HEALTH CARE This electronic document was made available from www.rand.org as a public service INFRASTRUCTURE AND of the RAND Corporation. TRANSPORTATION INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS LAW AND BUSINESS Skip all front matter: Jump to Page 16 NATIONAL SECURITY POPULATION AND AGING PUBLIC SAFETY Support RAND SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY Purchase this document TERRORISM AND Browse Reports & Bookstore HOMELAND SECURITY Make a charitable contribution For More Information Visit RAND at www.rand.org Explore the RAND National Security Research Division View document details Limited Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law as indicated in a notice appearing later in this work. This electronic representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for non- commercial use only. Unauthorized posting of RAND electronic documents to a non-RAND website is prohibited. RAND electronic documents are protected under copyright law. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of our research documents for commercial use. For information on reprint and linking permissions, please see RAND Permissions. This product is part of the RAND Corporation monograph series. RAND mono- graphs present major research findings that address the challenges facing the public and private sectors. All RAND monographs undergo rigorous peer review to ensure high standards for research quality and objectivity. Leadership Stability in Army Reserve Component Units Thomas F. Lippiatt, J. Michael Polich NATIONAL SECURITY RESEARCH DIVISION Leadership Stability in Army Reserve Component Units Thomas F. -

This Index Lists the Army Units for Which Records Are Available at the Eisenhower Library

DWIGHT D. EISENHOWER LIBRARY ABILENE, KANSAS U.S. ARMY: Unit Records, 1917-1950 Linear feet: 687 Approximate number of pages: 1,300,000 The U.S. Army Unit Records collection (formerly: U.S. Army, U.S. Forces, European Theater: Selected After Action Reports, 1941-45) primarily spans the period from 1917 to 1950, with the bulk of the material covering the World War II years (1942-45). The collection is comprised of organizational and operational records and miscellaneous historical material from the files of army units that served in World War II. The collection was originally in the custody of the World War II Records Division (now the Modern Military Records Branch), National Archives and Records Service. The material was withdrawn from their holdings in 1960 and sent to the Kansas City Federal Records Center for shipment to the Eisenhower Library. The records were received by the Library from the Kansas City Records Center on June 1, 1962. Most of the collection contained formerly classified material that was bulk-declassified on June 29, 1973, under declassification project number 735035. General restrictions on the use of records in the National Archives still apply. The collection consists primarily of material from infantry, airborne, cavalry, armor, artillery, engineer, and tank destroyer units; roughly half of the collection consists of material from infantry units, division through company levels. Although the collection contains material from over 2,000 units, with each unit forming a separate series, every army unit that served in World War II is not represented. Approximately seventy-five percent of the documents are from units in the European Theater of Operations, about twenty percent from the Pacific theater, and about five percent from units that served in the western hemisphere during World War II. -

The Brigade Combat Team (BCT): a Revolution in Organizational Structure

University of Southern Maine USM Digital Commons Muskie School Capstones and Dissertations Student Scholarship 12-2020 The Brigade Combat Team (BCT): A Revolution in Organizational Structure Adam Davis University of Southern Maine, Muskie School of Public Service Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usm.maine.edu/muskie_capstones Part of the Defense and Security Studies Commons, Infrastructure Commons, Military and Veterans Studies Commons, Nonprofit Administration and Management Commons, Operations and Supply Chain Management Commons, Organizational Behavior and Theory Commons, and the Policy Design, Analysis, and Evaluation Commons Recommended Citation Davis, Adam, "The Brigade Combat Team (BCT): A Revolution in Organizational Structure" (2020). Muskie School Capstones and Dissertations. 165. https://digitalcommons.usm.maine.edu/muskie_capstones/165 This Capstone is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship at USM Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Muskie School Capstones and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of USM Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Brigade Combat Team (BCT): A Revolution in Organizational Structure Adam Davis Capstone paper for Master of Policy, Planning, and Management Program Muskie School of Public Service University of Southern Maine December 2020 Professor Joseph McDonnell, Capstone Advisor THE BRIGADE COMBAT TEAM (BCT) 2 Abstract This paper explores the U.S. Army’s force reorganization around the Brigade Combat Team (BCT), which began in 2002. The BCT shifted how various army units interacted by changing the echelon at which different types of units report to a single commander, essentially creating self-sufficient units of about 2,500 soldiers instead of the previous self-sufficient units of about 15,000 soldiers. -

All but War Is Simulation: the Military Entertainment Complex

1 THEATERS OF WAR: THE MILITARY-ENTERTAINMENT COMPLEX Tim Lenoir and Henry Lowood Stanford University To appear in Jan Lazardzig, Helmar Schramm, Ludger Schwarte, eds., Kunstkammer, Laboratorium, Bühne--Schauplätze des Wissens im 17. Jahrhundert/ Collection, Laboratory, Theater, Berlin; Walter de Gruyter Publishers, 2003 in both German and in English War games are simulations combining game, experiment and performance. The U.S. Department of Defense (DoD) has been the primary proponent of war game design since the 1950s. Yet, commercial game designers produced many of the ideas shaping the design of military simulations, both before and after the advent of computer-based games. By the 1980s, the seeds of a deeper collaboration among military, commercial designers, the entertainment industry, and academic researchers in the development of high-end computer simulations for military training had been planted. They built “distributed interactive simulations” (DIS) such as SIMNET that created virtual theaters of war by linking participants interacting with distributed software or hardware simulators in real time. The simulators themselves presented synthetic environments—virtual worlds—by utilizing advances in computer graphics and virtual reality research. With the rapid development of DIS technology during the 1990s, content and compelling story development became increasingly important. The necessity of realistic scenarios and backstory in military simulations led designers to build databases of historical, geographic and physical data, reconsider the role of synthetic agents in their simulations and consult with game design and entertainment talents for the latest word on narrative and performance. Even when this has not been the intention of their designers and sponsors, military simulations have been deeply embedded in commercial forms of entertainment, for example, by providing content and technology deployed in computer and video games. -

The U.S. Military's Force Structure: a Primer

CHAPTER 2 Department of the Army Overview when the service launched a “modularity” initiative, the The Department of the Army includes the Army’s active Army was organized for nearly a century around divisions component; the two parts of its reserve component, the (which involved fewer but larger formations, with 12,000 Army Reserve and the Army National Guard; and all to 18,000 soldiers apiece). During that period, units in federal civilians employed by the service. By number of Army divisions could be separated into ad hoc BCTs military personnel, the Department of the Army is the (typically, three BCTs per division), but those units were biggest of the military departments. It also has the largest generally not organized to operate independently at any operation and support (O&S) budget. The Army does command level below the division. (For a description of not have the largest total budget, however, because it the Army’s command levels, see Box 2-1.) In the current receives significantly less funding to develop and acquire structure, BCTs are permanently organized for indepen- weapon systems than the other military departments do. dent operations, and division headquarters exist to pro- vide command and control for operations that involve The Army is responsible for providing the bulk of U.S. multiple BCTs. ground combat forces. To that end, the service is orga- nized primarily around brigade combat teams (BCTs)— The Army is distinct not only for the number of ground large combined-arms formations that are designed to combat forces it can provide but also for the large num- contain 4,400 to 4,700 soldiers apiece and include infan- ber of armored vehicles in its inventory and for the wide try, artillery, engineering, and other types of units.1 The array of support units it contains. -

Military and Army Acronyms, Abbreviations, and Terms

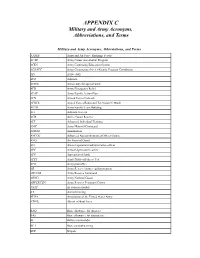

APPENDIX C Military and Army Acronyms, Abbreviations, and Terms Military and Army Acronyms, Abbreviations, and Terms AAFES Army and Air Force Exchange Service ACAP Army Career and Alumni Program ACES Army Continuing Education System ACS/FPC Army Community Service/Family Program Coordinator AD Active duty ADJ Adjutant ADSW Active duty for special work AER Army Emergency Relief AFAP Army Family Action Plan AFN Armed Forces Network AFRTS Armed Forces Radio and Television Network AFTB Army Family Team Building AG Adjutant General AGR Active Guard Reserve AIT Advanced Individual Training AMC Army Materiel Command AMMO Ammunition ANCOC Advanced Noncommissioned Officer Course ANG Air National Guard AO Area of operations/administrative officer APC Armored personnel carrier APF Appropriated funds APFT Army Physical Fitness Test APO Army post office AR Army Reserve/Army regulation/armor ARCOM Army Reserve Command ARNG Army National Guard ARPERCEN Army Reserve Personnel Center ASAP As soon as possible AT Annual training AUSA Association of the United States Army AWOL Absent without leave BAQ Basic allowance for quarters BAS Basic allowance for subsistence BC Battery commander BCT Basic combat training BDE Brigade Military and Army Acronyms, Abbreviations, and Terms cont’d BDU Battle dress uniform (jungle, desert, cold weather) BN Battalion BNCOC Basic Noncommissioned Officer Course CAR Chief of Army Reserve CASCOM Combined Arms Support Command CDR Commander CDS Child Development Services CG Commanding General CGSC Command and General Staff College -

How to Use the Senior Member Education and Training Tools in Eservices

How to Use the Senior Member Education and Training Tools in eServices Contents Where do I find the tools that support the Senior Member Education and Training Program? .......... 2 How do I sign up for an online cohort for Volunteer University? ......................................................... 4 How do I enter Summary Conversation completion in my Accomplishments? ................................... 7 How do I enter conference credit in my Accomplishments? ................................................................ 9 How do I see what I have completed and what remains to be completed in a level? ....................... 11 As a member or Entry Validator, how do I enter the Path to Progression in Level 1 so a member is enrolled in the correct path for Level 2? ............................................................................................ 13 As a member, how do I submit a level that has been completed so that I might advance to the next level? ................................................................................................................................................... 15 As an Approval Authority, how do I approve a task for a member? .................................................. 16 As an Approval Authority, how do I approve a level so that a member can advance to the next level? ................................................................................................................................................... 18 How do I use the Member Path Status Report to find out what -

Histo Ry: Cohors I Batavorum

Legio XIIII Gemina Martia Victrix Cohors I Batavorum Cohors I Hamiorum Via Romana The Auxilia. From the early days of the Republic, the Roman army had supplemented its strength with auxiliary (literally “help”) troops. When people think of the Roman Army there is a tendency to think of the legions themselves and to forget the considerable con- tribution made to the Roman war machine by the numerous auxiliary cohorts that provided vital support in a number of areas. While the Roman legions were undeniably the most effective fighting force of their age, the Romans themselves had never managed to suc- cessfully develop their military forces beyond the legionary formations. Accordingly the lack of cavalry, archers, slingers, etc. was made good by recruiting non-Roman peoples into cohorts of 500 (quingenaria) and 1000 (milliaria) men. These tended to be one of three types; light infantry, cavalry or combined units of cavalry and infantry. Auxiliary troops were levied from the conquered provinces and were named after the lo- cality of origination. The period of service for an auxiliary soldier was roughly 25 years after which time he could be discharged with a small gratuity and, most precious of all, a diploma conferring Roman citizenship on himself and his heirs. For acts of bravery it was more likely that citizenship, either for individuals, or for the unit as a whole, was awarded. Cohorts and Alae, like the Legions, could be given honorary awards such as "VICTRIX" or carry an Imperial family name. Some units, for example COHORS I BRITTONUM MIL- LIARIA ULPIA TORQUATA PIA FIDELIS CIVIUM ROMANORUM, or COHORS I FIDA VARDULLORUM MILLIARIA EQUITATA CIVIUM ROMANORUM, could amass many ti- tles. -

Jews and the Roman Army: Perceptions and Realities1

JEWS AND THE ROMAN ARMY: PERCEPTIONS AND REALITIES1 Jonathan P. Roth Scholars, including military historians, often project the conventions of Talmudic, or even modern, Judaism back into previous periods. This is particularly true in general assumptions about Jews in the military 1 This note contains a select bibliography, some titles of which will be cited in the following footnotes. S. Applebaum, ‘Three Roman Soldiers of Probably Jewish Origin,’ in M. Rozelaar and B. Shimron, eds., Commentationes ad antiquitatem classicam pertinentes in memoriam B. Katz (Tel Aviv 1970). ——, ‘Ein Targhuna,’ in S. Applebaum, Judaea in Hellenistic and Roman Times: Historical and Archaeological Essays (Leiden 1989), 66–69. B. Bar-Kochva, The Seleucid Army: Organization and Tactics in the Great Campaigns (Cam- bridge 1976). P. Bilde, Flavius Josephus between Jerusalem and Rome (Shef\ eld 1988). M. Gichon, ‘Aspects of a Roman Army in War According to the Bellum Judaicum of Josephus’, in D. Kennedy and Ph. Freeman, eds., The Defence of the Roman and Byzantine East I. BAR International Series 297, I (Oxford 1986), 287–310. A. Goldsworthy, ‘Community Under Pressure: The Roman Army at the Siege of Jeru- salem,’ in A. Goldsworthy and I. Haynes, The Roman Army as a Community. Journal of Roman Archaeology Supplemental Series 34 (Portsmouth RI 1999). R. González Salinero, ‘El servicio militar de los judíos en el ejército romano,’ Aquila Legionis 4 (Madrid 2003), 45–91. M.H. Gracey, ‘The Armies of the Judaean Client Kings,’ in D. Kennedy and Ph. Free- man, eds., The Defence of the Roman and Byzantine East I. BAR International Series 297, I (Oxford 1986).