2009-Hagood.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

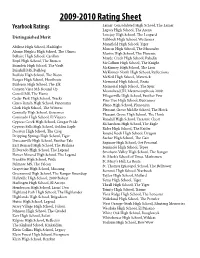

2009-2010 Rating Sheet

2009-2010 Rating Sheet Yearbook Ratings Lamar Consolidated High School, The Lamar Legacy High School, The Arena Lovejoy High School, The Leopard Distinguished Merit Lubbock High School, Westerner Mansfield High School, Tiger Abilene High School, Flashlight Marcus High School, The Marauder Alamo Heights High School, The Olmos Martin High School, The Phoenix Bellaire High School, Carillon Mayde Creek High School, Paladin Boyd High School, The Bronco McCallum High School, The Knight Brandeis High School, The Vault McKinney High School, The Lion Briarhill MS, Bulldog McKinney North High School, Reflections Buffalo High School, The Bison McNeil High School, Maverick Burges High School, Hoofbeats Memorial High School, Reata Burleson High School, The Elk Memorial High School, The Spur Canyon Vista MS, Round Up Moorehead JH, Metamoorphosis 2009 Carroll MS, The Flame Pflugerville High School, Panther Paw Cedar Park High School, Tracks Pine Tree High School, Buccaneer Cinco Ranch High School, Panorama Plano High School, Planonian Clark High School, The Witness Pleasant Grove Middle School, The Hawk Connally High School, Governor Pleasant Grove High School, The Hawk Coronado High School, El Viajero Randall High School, Treasure Chest Cypress Creek High School, Cougar Pride Richardson High School, The Eagle Cypress Falls High School, Golden Eagle Rider High School, The Raider Decatur High School, The Crag Round Rock High School, Dragon Dripping Springs High School, Tiger Sachse High School, The Gait Duncanville High School, Panther Tale Saginaw High School, Get Personal East Bernard High School, The Brahma Seminole High School, Tepee El Dorado High School, The Legend Smithson Valley High School, The Ranger Flower Mound High School, The Legend St. -

Leaguer, March/April 1982

March/April 1982 Volume 66 Number Seven The Leaguer USPS 267-840 Private, parochial school membership denied Private and parochial schools will not be able problem of attendance zones," Farney changing the basketball and volleyball completed. Use of the film for commercial joining the UIL. said. "Many private and parochial schools plans, permitting district executive com purposed must be approved by both schools. School administrators voted 919 to 64 recruit students from a large general area, mittees to make an exception to the two- Films and videotape become the property againt allowing non-public schools into the whereas public schools are limited by vari matched-contests-per-week rules when of the school filming, unless by district rule League as one measure in an eight-item re ous rules to play only students living within games are postponed by weather or public or mutual agreement otherwise. ferendum ballot, released during the girls' the general attendance zones. disasters. The games, however, must be • Making it a violation of the athletic state basketball tournament. "When this question is settled, I think played within the next seven days. plan to attend on-campus workouts which school administrators will be more willing involve meals and/or overnight lodging. In other major items, Conference to approve membership," he added. • Adding to the basketball plan limita AAAAA administrators narrowly defeated tions on eighth grade and below basketball • Adding to the "Foster Child Rule": A a proposal which would have eliminated The team tennis season will be played in teams to play no more than two matched student assigned to a home licensed by the spring football training, and approved the Conference AAAAA only. -

Texas PTA Reflections Results 2019 - 2020 Look Within

Texas PTA Reflections Results 2019 - 2020 Look Within Student First Name Student Last Name State-Level Award Title of Work Student's School Name (Local PTA) Council PTA Name High School Dance Choreography Madeleine Birmingham Participation Breath of Life Newman Smith High School Carrollton Farmers Branch ISD Council of PTAs Hope Carmack Participation The State of the Heart Ray Braswell High School Denton ISD Council of PTAs Alyssa De La Cruz Award of Excellence Familiar Harlingen High School South Harlingen CISD Council of PTAs Veronica Fang Honorable Mention Meditation Lone Star Statewide PTA Region 13, Statewide PTA Olivia Frazier Honorable Mention Under the Surface Memorial High School Frisco ISD Council of PTAs Overall Award of Madeline Gulledge Lágrimas de Sai Lowery Freshman Center Allen ISD Council of PTAs Excellence Alexa Hamilton Honorable Mention Struggle Within Clark PTA Plano ISD Council of PTAs Cathleen Johnsen Participation When I'm On My Own Westbrook High School PTA Region 5, Beaumont ISD Karen Mira Lopez Award of Merit Self Destructive but Beautiful Lakeview Centennial High School Garland ISD Council of PTAs Madison Moore Participation Pretty on the Inside Harlan High School PTSA Northside ISD Council of PTAs Riley Rogers Participation Finding Yourself Steele Accelerated High School Northwest ISD Council of PTAs Annaliese Rose Participation In my head Midway High School Midway ISD Council of PTAs Michelle Salinas Participation Yielding W.B. Ray High School Corpus Christi CISD Council of PTAs Katie Simmons Award of Merit -

Summary of Sexual Abuse Claims in Chapter 11 Cases of Boy Scouts of America

Summary of Sexual Abuse Claims in Chapter 11 Cases of Boy Scouts of America There are approximately 101,135sexual abuse claims filed. Of those claims, the Tort Claimants’ Committee estimates that there are approximately 83,807 unique claims if the amended and superseded and multiple claims filed on account of the same survivor are removed. The summary of sexual abuse claims below uses the set of 83,807 of claim for purposes of claims summary below.1 The Tort Claimants’ Committee has broken down the sexual abuse claims in various categories for the purpose of disclosing where and when the sexual abuse claims arose and the identity of certain of the parties that are implicated in the alleged sexual abuse. Attached hereto as Exhibit 1 is a chart that shows the sexual abuse claims broken down by the year in which they first arose. Please note that there approximately 10,500 claims did not provide a date for when the sexual abuse occurred. As a result, those claims have not been assigned a year in which the abuse first arose. Attached hereto as Exhibit 2 is a chart that shows the claims broken down by the state or jurisdiction in which they arose. Please note there are approximately 7,186 claims that did not provide a location of abuse. Those claims are reflected by YY or ZZ in the codes used to identify the applicable state or jurisdiction. Those claims have not been assigned a state or other jurisdiction. Attached hereto as Exhibit 3 is a chart that shows the claims broken down by the Local Council implicated in the sexual abuse. -

Texas PTA Reflections Results 2019 - 2020 Look Within

Texas PTA Reflections Results 2019 - 2020 Look Within Student First Student Last Name State-Level Award Grade Division Arts Category Title of Work Student's School Name (Local PTA) Council PTA Name Name Addyson Abdelbaki Participation Primary Photography Find The Beauty Within Doss Elementary Austin ISD Council of PTAs Aanyah Abdullah Participation High School Photography Illuminated Within Westwood High School Round Rock ISD Council of PTAs Kesiah Ann Abraham Honorable Mention Intermediate Literature Look With in Yourself Sunnyvale Intermediate PTA Region 10, Sunnyvale ISD Simran Acharya Award of Merit Primary Literature Inside Me Olive Stephens Elementary School Denton ISD Council of PTAs Grapevine Colleyville ISD Council Jenna Achterberg Participation High School Photography Summer Skies Colleyville Heritage High School of PTAs Macy Adam Honorable Mention Primary Dance Choreography Inside of Me Mountain Valley Elementary School Comal ISD Council of PTAs Sarah Adams Participation Middle School Photography Desert Bush Hutchinson Middle School PTA Lubbock ISD Council of PTAs New Braunfels ISD Council of Ari Nathan Aguirre Participation Middle School Literature Looking Within New Braunfels Middle School PTAs Nadia Ahmed Honorable Mention Intermediate Photography Inside-Out Pecan Creek Elementary Denton ISD Council of PTAs Tasneem Ahmed Participation Intermediate Literature Anything Is Special Kiker Elementary Austin ISD Council of PTAs David Ahn Award of Excellence Primary Visual Arts Celebrating the Fish's Birthday Centennial Plano ISD -

2015-16 TGCA Volleyball Academic All-State Selections

2015-16 TGCA Volleyball Academic All-State Selections Athlete First Athlete Last High School Coach First Coach Last Conf. 1A Sara English ASPERMONT HIGH SCHOOL Rebekah Bland 1A Jacy Sparks ASPERMONT HIGH SCHOOL Rebekah Bland 1A Macy Higgins BLUM HIGH SCHOOL Lauren McPherson 1A Rhealee Spies BURTON HIGH SCHOOL Katie Cloud 1A Cali Porter FORT DAVIS HIGH SCHOOL Gary Lamar 1A Kristina Mayo GARY HIGH SCHOOL Tamika Hubbard 1A Sydney Ritter GARY HIGH SCHOOL Tamika Hubbard 1A Cheyenne Camp KNOX CITY HIGH SCHOOL Brenna Hoegger 1A Cortlyn Barnes MEDINA HIGH SCHOOL Lovey Sockol 1A Hannah Garrison MEDINA HIGH SCHOOL Lovey Sockol 1A Chyna Phillips MEDINA HIGH SCHOOL Lovey Sockol 1A Whitley Whitewood MEDINA HIGH SCHOOL Lovey Sockol 1A Aurora Denise Araujo MUNDAY SECONDARY SCHOOL Jessica Toliver 1A Skylar Gomez MUNDAY SECONDARY SCHOOL Jessica Toliver 1A Kimberly Shahan MUNDAY SECONDARY SCHOOL Jessica Toliver 1A Ana Vega MUNDAY SECONDARY SCHOOL Jessica Toliver 1A Kiera Cosby NORTH ZULCH HIGH SCHOOL Gregory Horn 1A Jasmine D Willis OAKWOOD HIGH SCHOOL Mike Hill 1A Kendall Deaton PADUCAH HIGH SCHOOL Sandra Tribble 1A Leslie Mayo PADUCAH HIGH SCHOOL Sandra Tribble 1A Madison Heyman ROUND TOP‐CARMINE HIGH SCHOOL RaChelle Etzel 1A Adyson Lange ROUND TOP‐CARMINE HIGH SCHOOL RaChelle Etzel 1A Emma Leppard ROUND TOP‐CARMINE HIGH SCHOOL RaChelle Etzel 1A Cheyenne Janssen RUNGE HIGH SCHOOL Melissa Lopez 1A Brittany Rauch STERLING CITY HIGH SCHOOL Amelia Reeves 1A Verenise Aguirre TIOGA SCHOOL Mindy Patton 1A Samantha Holcomb TIOGA SCHOOL Mindy Patton 1A Heather -

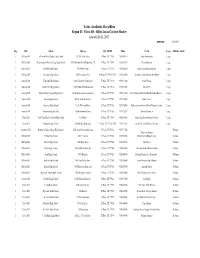

3Frdtl01.P 83-4 Pine Tree ISD, TX 02/15/17 Page:1 05.17.02.00.00 DISBURSEMENTS for BOARD REVIEW (Dates: 01/01/17 - 01/31/17) 9:00 AM

3frdtl01.p 83-4 Pine Tree ISD, TX 02/15/17 Page:1 05.17.02.00.00 DISBURSEMENTS FOR BOARD REVIEW (Dates: 01/01/17 - 01/31/17) 9:00 AM CHECK CHECK ACCOUNT INVOICE INVOICE DATE NUMBER AMOUNT VENDOR NUMBER DESCRIPTION NUMBER 01/13/2017 161700968 41.20 A SHRED AHEAD 199 E 51 6259 00 001 0 99 SHD SHREDDING SERVICES 2016-2017 616063 01/13/2017 161700968 26.50 A SHRED AHEAD 199 E 51 6259 00 041 0 99 SHD SHREDDING SERVICES 2016-2017 616064 01/13/2017 161700968 35.54 A SHRED AHEAD 199 E 51 6259 00 043 0 99 SHD SHREDDING SERVICES 2016-2017 616055 01/13/2017 161700968 35.54 A SHRED AHEAD 199 E 51 6259 00 103 0 99 SHD SHREDDING SERVICES 2016-2017 616061 01/13/2017 161700968 35.54 A SHRED AHEAD 199 E 51 6259 00 104 0 99 SHD SHREDDING SERVICES 2016-2017 616060 01/13/2017 161700968 26.50 A SHRED AHEAD 199 E 51 6259 00 105 0 99 SHD SHREDDING SERVICES 2016-2017 616056 01/13/2017 161700968 41.20 A SHRED AHEAD 199 E 51 6259 00 999 0 99 SHD SHREDDING SERVICES 2016-2017 616059 01/13/2017 161700968 35.54 A SHRED AHEAD 199 E 51 6259 00 999 0 99 SHD SHREDDING SERVICES 2016-2017 616058 01/27/2017 161701038 72.00 A#1 TROPHIES & PLAQU 199 E 41 6499 10 750 0 99 P00 BRASS PLATES FOR ROLL OF 41189 HONOR FOR RETIREES 01/13/2017 161700969 10.40 ABC AUTO PARTS INC 199 E 34 6319 01 999 0 99 000 PARTS FOR TRANSPORTATION 18-75724 VEHICLES FOR REMAINDER OF OCT NOVEMBER AND DECEMBER AND JANUARY 01/13/2017 161700969 48.62 ABC AUTO PARTS INC 199 E 34 6319 01 999 0 99 000 PARTS 18-75875 01/13/2017 161700969 39.97 ABC AUTO PARTS INC 199 E 34 6319 01 999 0 99 000 PARTS 18-75821 -

Many Stars Come from Texas

MANY STARS COME FROM TEXAS. t h e T erry fo un d atio n MESSAGE FROM THE FOUNDER he Terry Foundation is nearing its sixteenth anniversary and what began modestly in 1986 is now the largest Tprivate source of scholarships for University of Texas and Texas A&M University. This April, the universities selected 350 outstanding Texas high school seniors as interview finalists for Terry Scholarships. After the interviews were completed, a record 165 new 2002 Terry Scholars were named. We are indebted to the 57 Scholar Alumni who joined the members of our Board of Directors in serving on eleven interview panels to select the new Scholars. These freshmen Scholars will join their fellow upperclass Scholars next fall in College Station and Austin as part of a total anticipated 550 Scholars: the largest group of Terry Scholars ever enrolled at one time. The spring of 2002 also brought graduation to 71 Terry Scholars, many of whom graduated with honors and are moving on to further their education in graduate studies or Howard L. Terry join the workforce. We also mark 2002 by paying tribute to one of the Foundations most dedicated advocates. Coach Darrell K. Royal retired from the Foundation board after fourteen years of outstanding leadership and service. A friend for many years, Darrell was instrumental in the formation of the Terry Foundation and served on the Board of Directors since its inception. We will miss his seasoned wisdom, his keen wit, and his discerning ability to judge character: all traits that contributed to his success as a coach and recruiter and helped him guide the University of Texas football team to three national championships. -

THECB Appendices 2011

APPENDICES to the REPORTING and PROCEDURES MANUALS for Texas Universities, Health-Related Institutions, Community, Technical, and State Colleges, and Career Schools and Colleges Summer 2011 TEXAS HIGHER EDUCATION COORDINATING BOARD Educational Data Center TEXAS HIGHER EDUCATION COORDINATING BOARD APPENDICES TEXAS UNIVERSITIES, HEALTH-RELATED INSTITUTIONS, COMMUNITY, TECHNICAL, AND STATE COLLEGES, AND CAREER SCHOOLS Revised Summer 2011 For More Information Please Contact: Doug Parker Educational Data Center Texas Higher Education Coordinating Board P.O. Box 12788 Austin, Texas 78711 (512) 427-6287 FAX (512) 427-6147 [email protected] The Texas Higher Education Coordinating Board does not discriminate on the basis of race, color, national origin, gender, religion, age or disability in employment or the provision of services. TABLE OF CONTENTS A. Institutional Code Numbers for Texas Institutions Page Public Universities .................................................................................................................... A.1 Independent Senior Colleges and Universities ........................................................................ A.2 Public Community, Technical, and State Colleges................................................................... A.3 Independent Junior Colleges .................................................................................................... A.5 Texas A&M University System Service Agencies .................................................................... A.5 Health-Related -

TAD Region Setup from TAD DATABASE.Xlsx

Texas Academic Decathlon Region II - Ysleta HS - Billye Lucas/Carolyn Mackey January 20-21, 2017 UPDATED: 9/15/2016 Reg. ISD School Address City, ST ZIP Phone Coach Large Medium Small 2 El Paso ISD Jefferson/Silva Magnet High School 121 Val Verde Street El Paso, TX 79905 9154968010 Adan Armendariz Large 2 El Paso ISD Transmountain Early College High School 9570 Gateway North Boulevard, EC El Paso, TX 79924 9158324270 Mario Guzman Large 2 El Paso ISD Franklin High School 900 North Resler El Paso, TX 79912 9152362200 Andrew Long/James Barton Large 2 El Paso ISD Coronado High School 100 Champions Place El Paso, TX 79912-3799 9152362000 Alexander Seufert/Matthew Ballway Large 2 Socorro ISD El Dorado High School 12401 Edgemere Boulevard El Paso, TX 79938 9159373200 Paula Woods Large 2 Socorro ISD Pebble Hills High School 14400 Pebble Hills Boulevard El Paso, TX 79938 9159379400 Maria Paiz Large 2 Socorro ISD Mission Early College High School 10700 Gateway Boulevard East El Paso, TX 79927 9159371200 Drew Dungan/Elizabeth Bonilla/Joshua Brewer Large 2 Socorro ISD Socorro High School 10150 Alameda Avenue El Paso, TX 79927 9159372000 Juan J. Garcia Large 2 Socorro ISD Americas High School 12101 Pellicano Drive El Paso, TX 79936 9159372800 Robert Strawn/Steven Morrel/Virginia Gardea Large 2 Socorro ISD Montwood High School 12000 Montwood Drive El Paso, TX 79936 9159372478 Daniela Gonzalez Large 2 Ysleta ISD Valle Verde Early College High School 919 Hunter El Paso, TX 79915 9154341500 James Alan Brown/Kenneth Porter Large 2 Ysleta ISD Eastwood High School 2430 McRae Boulevard El Paso, TX 79925-7225 9154344121 Nicole O'Leary/Christine O'Leary Large 2 Canutillo ISD Northwest Early College High School 6701 South Desert Boulevard El Paso, TX 79932 9158771706 Medium Francesca Alonso 2 El Paso ISD El Paso High School 800 E. -

During the 2004-2005 Academic Year, Six Hundred Two Outstanding Young Texans Attended Four of the State's Finest Universities As Terry Scholars

,e E. Baggett, Carolyn J. Barber, Abigail K. Barnett, Alexandra C. Baron, Antonio J. Barrera, Keith J. Batla, Anna M. B e a c h , :ga, Zachary J. Bevis, Autumn R. Billimek, Brock L. Birkenfeld, Steven C. Blackmon, Aaron L. B lac km or, Ashley A. B lah a, Bradbury, Alexander D. Brand, Alex L. Brandt, Chara R. Bray, Laura C. Bredeson, Jennifer Brewer, David P. B r e w e r t o n , n, Tara E. Buentello, Kenneth Burkhalter, Vermique J. Burton, Brandy C. Butler, Leslie A. Caballero, Zachary W. Cadwalader, „ Courtney A. Carm icheal, M arci L. C arrillo, Lindsey M. Carter, Rachael E. Carter, Tametrice L. Chatham, Jillian R. C h r i s ma n , nton, Bonnie R. Cole, H. Eshe Cole, Kindra D. Coleman, Simmie J. Colson IV, Yvonne C. Cook, Stephanie M. C o r d e r , loker, Cassandra V. Cuellar, M onica V. Culver, Kristen M. Cummings, Caitlin Y. Cunniff, Teresa C. Cupp, Casey E. C u r r i e , *e A. Davidson, M ia B. De Pinto, J. Cuyler Dear, Eric L. DeBerry, Jose A. Del Valle, Donald Delgado, Nidia B. Delgado, H o l l y R. Dockal, Quentin A. Donnellan, J. Kate Douglas, Shelby C Downs, M itchell A. Drennan, Kathleen A. D r i l l i n g , d Escalante III, S t e p h a n ie L. Espinoza, Travis W. Eubanks, Jodi L. E y h o rn , G r a n t R. Faber, Carson L. Fairbanks, M ary K. F a r m a n , stesto Fong, Patrick M. -

2010-2011 Rating Sheet

2010-2011 Rating Sheet Yearbook Ratings Jersey Village High School, Falcon Johnson High School, The Citadel Distinguished Merit Kerr High School, Safari Klein High School, Bearkat A & M Consolidated High School, Tigerland Klein Collins High School, Legacy Alamo Heights High School, The Olmos Klein Forest High School, Evergreen Allen High School, The Eagle La Grange High School, Leopard Spots Archer City High School, Wildcat Langham Creek High School, Lobo Lair Azle High School, The Hornet Legacy High School, The Arena Bellaire High School, Carillon Lovejoy High School, The Leopard Boyd High School, The Bronco Lubbock High School, Westerner Brandeis High School, The Vault Mansfield High School, The Tiger Briarhill Middle School, The Bulldog Martin High School, Phoenix Brownsboro High School, Bear Tracks McCallum High School, The Knight Buffalo High School, The Bison McKinney High School, The Lion Burges High School, Hoofbeats McKinney North High School, Reflections Burkburnett Middle School, Texan McNeil High School, Maverick Burleson High School, The Elk Houston Memorial High School, Reata Canyon High School, Soaring Wings McAllen Memorial High School, The Spur Canyon Vista Middle School, Round Up Moorhead Junior High, Roar 2010 Carroll Middle School, The Flame Nazareth High School, Swift Cedar Park High School, Tracks Pine Tree High School, Buccaneer Channing High School, The Eagle Plano High School, Planonian Cinco Ranch High School, Panorama Pleasant Grove High School, The Hawk Clark High School, The Witness Pleasant Grove Middle School,