CODA LARS NITTVE Could It Be That the Quiet Yet Radical Dismantling Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ART HK 12 by Jing Daily Published: May 17, 2012

ART HK 12 By Jing Daily Published: May 17, 2012 5th annual Hong Kong International Art Fair The global art world descends upon Hong Kong for the opening of ART HK 12, running from 17 to 20 May, 2012 at the Hong Kong Convention and Exhibition Centre (HKCEC). The 2012 edition, once again sponsored by Deutsche Bank, presents 266 galleries from 38 countries – and is set to top all previous attendance records. Now in its fifth year, ART HK 12 has achieved global significance in the international art scene attracting a rich mix of audience from both the West and East, and has cemented itself as a firm fixture on the global art circuit. Hong Kong is unparalleled as a location for a major destination art fair in the region, and ART HK has built a solid reputation for its outstanding quality and extraordinary variety showcasing the best international galleries alongside emerging artists and galleries from across Asia and the globe. Speaking at the opening, Magnus Renfrew, Fair Director said, “We are delighted once again to welcome such a high calibre of art from around the world to ART HK 12. It’s extremely exciting to see the Fair progress with the support of Deutsche Bank and it’s hugely promising that in its fifth year it continues to attract new participating galleries. Asia is now clearly center stage”. Friedhelm Hütte, Global Head of Art, Corporate Citizenship for Deutsche Bank commented, “The arts are a key cornerstone of Deutsche Bank’s social responsibility program. We look forward to http://www.jingdaily.com/art-hk-12/18268/ seeing the very best in both Eastern and Western contemporary art come together at this year’s ART HK, and building on our ongoing partnership with Asia’s leading art fair”. -

Contemporaneity” in Public Museums of Art and Visual Culture in the 21St Century

Framing “contemporaneity” in public museums of art and visual culture in the 21st Century A study of the impact of acquisition policies of the Moderna Museet and M+ through the lens of actor-network theories Lam Chi Hang, Jims Department of Culture and Aesthetics Degree: Master’s thesis, 30 HE credits Subject: Curating Art International Master’s Programme in Curating Art, including Management and Law, 120 HE credits Spring term 2021 Supervisor: Eva Aggeklint Framing “contemporaneity” in public museums of art and visual culture in the 21st Century A study of the impact of acquisition policies of the Moderna Museet and M+ through the lens of actor-network theories Lam Chi Hang, Jims Abstract In the 21st century, public museums who are collecting contemporary art has simultaneously begun to reframe the role of museums in society. Two museums – the Moderna Museet of Stockholm and M+ of Hong Kong that have completely different historic and geographic backgrounds, as well as operating models are now working closely with their acquisitions and collections to draw audience of old and new closer to them. These two museums that are located in the center of two well-defined cultures – geographically representing the west and the east, play vital roles in their respected social and cultural spheres. In view of how these two museums are responding to the present time by deploying art that are seemingly different in terms of theme and discipline, the immediate distinction that this study aims to frame is how the Moderna Museet, established in the 20th century and still prevailing in the present differ from M+ that comes from a younger generation of museums who proclaims itself as a museum of visual culture, and not art. -

Hilma Af Klint Ett Henneneutiskt Försök

LINKÖPINGS UNIVERSITET Institutionen för Tema Avd. för konst- och bildvetenskap Hilma af Klint ett henneneutiskt försök av Berit Maria Holm Linköpings Universitet Linköping University Institution för Tema Tema Department Avdelning för konst- och bildvetenskap Art and Visual Communication C-uppsats Essay; Art and Visual Communication 3 Handledare: Bengt Lärkner Supervisor: Bengt Lärkner November 1997 November 1997 Hilma af Klint ett henneneutiskt försök Berit Maria Holm SMvIMANFATTNING: Uppsatsen tar upp tretton bilder som Hi/ma afKlint målade under tidsperioden 1906-1915. Bilderna ingår i en svit som kallas för Bilderna lill Temp/et som omfattar nästan 190 målningar. Under hennes livstid var hennes livsverk okänt för hennes samtid. Hon målade abstrakta, geometriska former och använde klara färger flera år före sina samtida konstnärskollegor. Inom ett hermeneutiskt arbetssätt ingår det olika moment som tolkning, beskrivning och analys av bilder. Uppsatsen vill belysa och ta upp hennes formspråk ur symbolisk synvinkel med hjälp av den hermeneutiska arbetsrnodellen. Dels genom att göra hennes bildspråk mer begripligt och dels för att hitta gemensamma nämnare som ökar förståelsen för hennes målningar. Enligt författarens mening hade hon svårt för att förstå innehållet i bilderna, men hade en klar tanke om att bilderna speglade evolutionstanken i Skapeisen. NYCKELORD: Hi/ma afKlint, 1906-1915, Må/ningarna lill Temp/et, tretton bilder, hermeneutik. sPRÅK: Svenska Hilma af Klint a henneneutical attempt Berit Maria Holm ABSTRACT: The essay includes thirteen pictures by Hi/ma afKlint, who painted these between 1906-1915. The pictures is a part ofa suite namned The Pailnings lo Ihe Temp/e which extent almost 190 paintings. During her lifetime her life's work was unknown to her own period. -

Anders Knutsson

ANDERS KNUTSSON RADICAL PAINTING - MEDITATIONS ON THE MONOCHROME FOR SALE AT BUKOWSKIS STOCKHOLM TABLE OF CONTENTS MARCH 25 - APRIL 3, 2011 MICHAEL STORÅKERS – RADICAL PAINTING 4 BO NILSSON – MONOCHROME MEDITATIONS 5 PLEASE CONTACT: LISA IVEMARK - HEAD OF SALES/CUSTOMER RELATIONS DAVID NEUMAN – SEEING – AN ESSAY BY DAVID NEUMAN FROM 1981 6 + 46 (0) 8 - 614 08 17. EMAIL: [email protected] LARS NITTVE – A MONOCHROME STORY 8 ANDERS KNUTSSON – RADICAL PAINTING MEDITATIONS ON THE MONOCHROME 10 BUKOWSKIS, ARSENALSGATAN 4, STOCKHOLM, SWEDEN. PAINTINGS 14 + 46 (0) 8 - 614 08 00 WWW.BUKOWSKIS.COM BIOGRAPHY 36 religion. Over time, Anders Knutsson weaned himself off his THANK YOU ANDERS KNUTSSON addiction to Barnett Newman. In the painting “Regatta” from 1975, all traces of the vertical form have been replaced by a colour field that the artist has applied homogenously over To work with art in your everyday life is to be continually sur- – MONOCHROME the entire canvas using a palette knife. His use of transpa- prised and challenged. When I entered art, and its essence rent beeswax in the paint has created a virtually atmospheric had begun to open up, I soon realised the huge complexity space that seemingly appears to be a remnant from the era involved. Just when you have managed to grasp one mo- MEDITATIONS of open-air painting with an almost impressionistic treat- vement, one era, one taste, one group of artists, everything ment of the paint. Here we have a spatiality with no shape or becomes contradicted by something else, even the opposi- specific point on which to fix one’s gaze. -

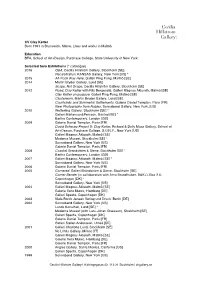

CV Clay Ketter Born 1961 in Brunswick, Maine. Lives and Works in Malmö

CV Clay Ketter Born 1961 in Brunswick, Maine. Lives and works in Malmö. Education BFA, School of Art+Design, Purchase College, State University of New York Selected Solo Exhibitions (* catalogue) 2016 Q&A, Cecilia Hillström Gallery, Stockholm [SE] Recalcitration, KANSAS Gallery, New York [US] * 2015 Ah Pook Was Here, Galleri Ping Pong, Malmö [SE] 2014 Martin Bryder Gallery, Lund [SE] Scope, Not Scape, Cecilia Hillström Gallery, Stockholm [SE] 2012 Road, Clay Ketter with Nils Bergendal, Galleri Magnus Åklundh, Malmö [SE] Clay Ketter on purpose, Galleri Ping-Pong, Malmö [SE] Clusterwork, Martin Bryder Gallery, Lund [SE] Courtyards and Symmetric Settlements, Galerie Daniel Templon, Paris [FR] New Photographs from Naples, Sonnabend Gallery, New York, [US] 2010 Wetterling Gallery, Stockholm [SE] * Galleri Mårtenson&Persson, Båstad [SE] * Bartha Contemporary, London [GB] 2009 Galerie Daniel Templon, Paris [FR] David Schwarz Project II: Clay Ketter, Richard & Dolly Maas Gallery, School of Art+Design, Purchase College, S.U.N.Y., New York [US] Galleri Magnus Åklundh, Malmö [SE] Moderna Museet, Stockholm [SE] * Sonnabend Gallery, New York [US] Galerie Daniel Templon, Paris [FR] 2008 Coastal, Brandström & Stene, Stockholm [SE] * Bartha Contemporary, London [GB] 2007 Galleri Magnus Åklundh, Malmö [SE] * Sonnabend Gallery, New York [US] 2006 Galerie Daniel Templon, Paris [FR] 2005 Cornered, Galleri Brändström & Stene, Stockholm [SE] Corner Bender (in collaboration with Arno Brandlhuber, B&K+), Box 2.0, Copenhagen [DK] * Sonnabend Gallery, New York -

Lee Kit's Hong Kong Exhibition at the Venice Biennale

Querying The Quotidian: Lee Kit’s Hong Kong Exhibition at the Venice Biennale The artist Lee Kit has been selected to represent Hong Kong in their exhibition at the 55th International Art Exhibition in Venice - La Biennale di Venezia. Curated by Lars Nittve along with Yung Ma of prospective Hong Kong gallery M+, they will display an exhibition entitled You (you), which questions identity and its myriad manifestations within quotidian life. The curator of the 2013 Venice Biennale — the 55th incarnation of the event - is Massimiliano Gioni. He has entitled the space and theme of the event ‘Il Palazzo Enciclopedico’ or ‘The Encyclopedic Palace’. The dream offered by this idea is the desire to both see and know everything; it is a show about obsessions and the transformative power of the imagination. Gioni affirms that ‘The Encyclopedic Palace... is a show that illustrates a condition we all share: we ourselves are media, channelling images, or at times even finding ourselves possessed by images.’ You (you) shares a specific framework of thought with Gioni: Kit’s exhibit incorporates various elements of artistic creativity to evoke the textures of both real and imagined memories. Conceived through recollections of the artist’s own personal and collective moments, the ‘artist’s world’ (in the words of Gioni) is visually articulated through Kit’s use of mixed media. For the first time, the 2013 co-presentation and selection comes from the Hong Kong Arts Development Council (HKADC), which has adopted a model which has been successfully utilised in many other participating countries, where an esteemed local arts body or institution is given the responsibility to select the curator and the artist to represent their country. -

新聞報刊 the Peak Hong Kong Primary Powers May 2014

THE ARTS PRIMARY POWERS TOBIAS BERGER If you follow and invest in the burgeoning art scene in Hong Kong, Curator of M+ SHIRLEY almost inevitably, you’ll wind up in the company of these people, YABLONSKY who are helping to define the direction of art in the city. Director of Opera Gallery SIMON BIRCH TEXT RAYMOND MA, ANDREW DEMBINA & LIANA CAFOLLA SIN SIN MAN HK-based Artist PHOTOGRAPHY GARETH GAY ASSISTED BY PERRY TSE ART DIRECTION & GROOMING GRACE MA Owner of Sin Sin Fine Art LARS NITTVE SUNDARAM M+ Chief Curator TAGORE Owner of OSCAR HO HING-KAY REBECCA WEI Sundaram Tagore Director of President of Gallery Hong Kong LI YAN M.A. Programme in Christie’s Asia Director of Cultural Management at MICHAEL LYNCH the Chinese University CEO of West (excluding China) Lehmann of Hong Kong Kowloon Cultural Maupin District Authority ALICE MONG Executive Director of Asia Society FRANK Hong Kong Center VIGNERON Curator and Professor of CUHK Department of Fine Arts THE BOSSES THE PROVIDERS THE VOICES 64 THE PEAK P064-077_Feature_Art Primary Powers_OP3.indd 64 4/12/14 4:42 PM Feature_Art Primary Powers_Gatefold1.indd 12 4/10/14 12:05 AM Feature_Art Primary Powers_Gatefold2.indd 12 4/10/14 12:06 AM THE ARTS ALICE MONG EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR Asia Society Hong Kong Center Before returning to Hong Kong in will start realising that it is cool,” “I AM NOT A 2012, Alice Mong spent a decade says the executive director of Asia COLLECTOR. in arguably the world’s cultural Society Hong Kong Center. “The capital, New York. -

ART BASEL CITIES BIOGRAPHIES Art Basel Cities Global Advisory Board Patrick Foret, Chair of the Board

ART BASEL CITIES BIOGRAPHIES Art Basel Cities Global Advisory Board Patrick Foret, Chair of the Board; Director of Business Initiatives, Art Basel Before being promoted to Director of Business Initiatives as well as creating and launching the Art Basel Cities Initiatives, Patrick Foret had been Art Basel’s Head of Sponsorship since September 2010. He played a key role in strengthening the Art Basel corporate partnership program by driving partners to develop and deliver art engagement strategies that contribute meaningfully to the art world. Patrick was also the lead figure behind the creation and successful launch of the Art Basel Crowdfunding initiative. Before that, Patrick was in charge, as Business Manager, of the Louvre and the Guggenheim Abu Dhabi museum projects. Previously, Patrick ran his own business and was involved in many art-related activities in Australia and Japan. A French native, he graduated from Sorbonne University in Paris with a Masters in International Commerce and a BA in Japanese language. He was a guest researcher for two years at Waseda University in Tokyo Japan. David Adjaye David Adjaye OBE is recognised as a leading architect of his generation. Adjaye was born in Tanzania to Ghanaian parents and his influences range from contemporary art, music and science to African art forms and the civic life of cities. In 1994 he set up his first office, reformed as Adjaye Associates in 2000 and now has four international offices, with projects throughout the world, frequently collaborating with contemporary artists on art and installation projects. Adjaye has taught at the Royal College of Art and at the Architectural Association School in London, and has held distinguished professorships at the universities of Pennsylvania, Yale and Princeton. -

Re-Thinking Surrealism: Shock, Disturb and Surprise Stockholm 21 - 22 November 2009

Re-thinking Surrealism: Shock, Disturb and Surprise Stockholm 21 - 22 November 2009 Salvador Dalí Foto: Anna Riwkin Re-thinking Surrealism: Shock, Disturb and Surprise Stockholm 21 - 22 November 2009 In late November, a few of the world’s most prominent experts on Dalí will gather in Stockholm for a two-day international symposium, Re-thinking Surrealism: Shock, Disturb and Surprise. Speakers from the UK, Spain, France, Italy and the USA will give highlights from recent research on Salvador Dalí and surrealism. Discussions on some of the theories behind the exhibition Dalí Dalí featuring Francesco Vezzoli will analyse Dalí’s influence on contemporary artists such as Francesco Vezzoli. Welcome to two days of talks and presentations, including unique documentary film footage. The symposium is intended for researchers in related fields and the art-loving public. Arranged by Moderna Museet in collaboration with the Centre for the Study of Surrealism and its Legacies, University of Manchester, Instituto Cervantes, Stockholm University and Södertörn University. Sponsored by Stiftelsen Riksbankens Jubileumsfond. Venue Moderna Museet, Auditorium Time 21-22 November, 11 am – 4 pm Tickets SEK 200 (Friends of Moderna Museet SEK 100), including refreshments and admission to the exhibition. Tickets can be booked through www.ticnet.se. Any remaining tickets will be sold at Moderna Museet on 21 November from 10 am. Languages English, Spanish (simultaneous interpretation) Contact Karin Malmquist, [email protected] Participants: Dawn Ades, professor of Art History, University of Essex, co-director of the Centre for the Study of Surrealism and its Legacies David Lomas, professor of Art History, University of Manchester, and co-director of Centre for the Study of Surrealism and its Legacies Pilar Parcerisas, Barcelona, PhD in Art History, art critic and curator Frédérique Joseph Lowery, PhD, art critic and exhibition curator William Jeffett, PhD, curator, Salvador Dalí Museum, St. -

James Welling Born 1951 in Hartford, Connecticut

This document was updated March 30, 2021. For reference only and not for purposes of publication. For more information, please contact the gallery. James Welling Born 1951 in Hartford, Connecticut. Lives and works in New York. EDUCATION 1971-1974 B.F.A. and M.F.A., California Institute of the Arts, Valencia 1970-1971 University of Pittsburgh 1969-1971 Carnegie Mellon University, Pittsburgh SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2021 Cento, Musée des Arts Contemporains, Hornu, Belgium [forthcoming] Metamorphosis, David Zwirner, Hong Kong 2020 Choreograph, George Eastman Museum, Rochester, New York [catalogue] The Earth, the Temple and the Gods, Galerie Marian Goodman, Paris Archaeology, Regen Projects, Los Angeles Archaeology, Regen Projects, Los Angeles [online presentation] Seascape, Portland Museum of Art, Portland, Maine 2019 Planograph, Maureen Paley, London Seascape by James Welling, Ogunquit Museum of American Art, Ogunquit, Maine Transform, David Zwirner, New York 2018 Choreograph, Galería Marta Cervera, Madrid Materials and Objects: James Welling and Zoe Leonard, Tate Modern, London [two-person exhibition] [collection display] 2017 Chronology, Marian Goodman Gallery, Paris Metamorph, LOGIN, Galerie nächst St. Stephan Rosemarie Schwarzwälder, Vienna Metamorphosis, Stedelijk Museum voor Actuele Kunst (S.M.A.K.), Ghent [itinerary: Kunstforum Wien, Vienna] [catalogue] New Work, Wako Works of Art, Tokyo Seascape, David Zwirner, New York 2016 Chronograph, Henry Art Gallery, University of Washington, Seattle Choreograph, Regen Projects, Los Angeles 2015 Choreograph, -

September/October 2013 Volume 12, Number 5 Inside

SEPTEMBER/OCTO B E R 2 0 1 3 V O LUME 12, NUMBER 5 INSI DE China, Hong Kong, and Taiwan at the 55th Venice Biennale Curatorial Inquiries 13: Who are the Connoisseurs? Interviews with Alexandra Munroe, Guggenheim Museum and Ted Lipman, Robert H. N. Ho Family Foundation The Quest for a Regional Culture: Two Trips to Bali Reviews: ON I OFF, Feng Yan US$12.00 NT$350.00 P RINTED IN TAIWAN 6 VOLUME 12, NUMBER 5, SEPTEMBER/OCTOBER 2013 CONTENTS Editor’s Note 29 Contributors 6 On Not Being Killed By Some Unfortunate Juxtaposition: The 2013 Venice Biennale Jo-Anne Birnie Danzker 29 On Chinese Art in Global Times: A Conversation with Wang Chunchen Alice Schmatzberger 38 38 To Be or Not to Be a National Pavilion: The Taiwan Pavilion and Hong Kong Pavilion at Venice Lu Pei-Yi 61 Curatorial Inquiries 13: Who are the Connoisseurs? Nikita Yingqian Cai and Carol Yinghua Lu 66 Interview with Alexandra Munroe, Samsung 77 Curator of Asian Art, Guggenheim Museum, New York Yu Hsiao Hwei 72 Interview with Ted Lipman, Chief Executive Officer of The Robert H. N. Ho Family Foundation Yu Hsiao Hwei 77 The Quest for a Regional Culture: The Artistic Adventure of Two Bali Trips, 1952 and 2001 88 Wang Ruobing 88 ON | OFF: China’s Young Artists in Concept and Practice Edward Sanderson 98 Feng Yan: Photography Objectified Jonathan Goodman 105 Chinese Name Index 98 Cover: Lee Kit, 'You (you).', installation, 2013 Venice Biennale. Courtesy of the Hong Kong Arts Development Council. We thank JNBY Art Projects, Canadian Foundation of Asian Art, Chen Ping, Mr. -

Message: Teenagers Into Art!

Symposium: Museum Education 21 Message: Teenagers into art! Lars Nittve (Director, Moderna Museet, Stockholm) The Moderna Museet in Stockholm has been with art. This idea of the close links between tried to convey. Could it be that we still slip working with art education since the early the small child and art has been present at into old romantic ideas – ideas that were 1960’s. Yet have I never heard the education least since the Enlightenment and escalated inherited by modernism – of the close af- curators being so encouraged in their work, during Romanticism to go into full bloom finity between “the artist, the fool and the as when they heard about the great interest during Modernism. It is therefore hardly sur- child”? This mindset is in direct conflict with for their new, innovative, programme for prising that educational activities for small a contemporary definition of art that, besides teenagers called Zon Moderna, from the just children were given prominence in the mod- pointing to the fundamental importance of opened and much talked about 21st Century el for European museums of modern art that the institution and the context in even be- Museum of Contemporary Art, Kanazawa, evolved in the 1950’s: The Stedelijk Museum ginning to define something as art, also em- Japan. in Amsterdam, The Louisiana Museum of phasises the extreme complexity of the work I think the happiness had two sources: Modern Art outside Copenhagen and last but of art. One particularly intriguing and rarely First and foremost the fact that colleagues not least the Moderna Museet in Stockholm.