A Panorama of Life

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Azadari in Lucknow

WEEKLY www.swapnilsansar.orgwww.swapnilsansar.org Simultaneously Published In Hindi Daily & Weekly VOL24, ISSUE 35 LUCKNOW, 07 SEPTEMBER ,2019,PAGE 08,PRICE :1/- Azadari in Lucknow Agency.Inputs With Sajjad Baqar- Lucknow is on the whole favourable to Madhe-Sahaba at a public meeting, and in protested, including prominent Shia Adeeb Walter -Lucknow.Azadari in Shia view." The Committee also a procession every year on the barawafat figures such as Syed Ali Zaheer (newly Lucknow is name of the practices related recommended that there should be general day subject to the condition that the time, elected MLA from Allahabad-Jaunpur), to mourning and commemoration of the prohibition against the organised place and route thereof shall be fixed by the Princes of the royal family of Awadh, district authorities." But the Government the son of Maulana Nasir a respected Shia failed to engage Shias in negotiations or mujtahid (the eldest son, student and inform them beforehand of the ruling. designated successor of Maulana Nasir Crowds of Shia volunteer arrestees Hussain), Maulana Sayed Kalb-e-Husain assembled in the compound of Asaf-ud- and his son Maulana Kalb-e-Abid (both Daula Imambada (Bara Imambara) in ulema of Nasirabadi family) and the preparation of tabarra, April 1939. brothers of Raja of Salempur and the Raja The Shias initiated a civil of Pirpur, important ML leaders. It was disobedience movement as a result of the believed that Maulana Nasir himself ruling. Some 1,800 Shias publicly Continue On Page 07 Imambaras, Dargahs, Karbalas and Rauzas Aasafi Imambara or Bara Imambara Imambara Husainabad Mubarak or Chhota Imambara Imambara Ghufran Ma'ab Dargah of Abbas, Rustam Nagar. -

Rainbow ,Class

Rainbow -Class 8 Lesson 1 Another Chance How often we wish for another chance, To make a fresh beginning. A chance to blot out our mistakes, And change failure into winning. It does not take a new day, To make a brand new start. It only takes a deep desire, To try with all our heart. To live a little better, And to always be forgiving. And to add a little sunshine, To the world in which we’re living. So never give up in despair, And think, you are through. For there’s always a tomorrow, And the hope of starting anew. -Helen Steiner Rice New Words Word Meaning often - असर mistake - -गलती desire -इछा despair -पणू िनराशा failure -असफलता Comprehension Questions 1. Answer the following questions: a. Why do we wish for another chance? b. What does it take to make a brand new start? c. Why should we never give up in despair? d. What lesson do we learn from the poem? 2. Match the following to complete the lines of the poem: ‘A’ ‘B’ a chance to blot out in despair it only takes sunshine to add a little a deep desire so never give up our mistakes Word Power 1. Read the poem and write the antonyms of the following words: 1.success_______ 2.old _______ 3.shallow _______ 4.never _______ 5.end _______ 6.despair _______ 2. Write three rhyming words for the words given below: 1.eight___ , ___ , ___ 2.face__ , __ , _ 3.chin____ , ___ , __ 4.new ____ , ____ , ____ Activity » A number has been given to each letter of the alphabet in the table below. -

Veer Abdul Hamid

Lesson -7 VEER ABDUL HAMID This is the story of a brave soldier named Abdul Hamid. He was a Company Quarter Master Havildar in the Indian Army. He was a very brave soldier. He fought in the 1965 war between India and Pakistan. Abdul Hamid was born in Dhamupur village of Ghazipur district in Uttar Pradesh on 1st July, 1933 in a muslim family to Sakina Begum and Mohammad Usman. Would you like to know how he became the hero of the 1965 war between India and Pakistan? It was the early morning of 10th September 1965, India was fighting against Pakistan. A Pakistani regiment of Patton Tanks was marching on the Bhikhiwind –Amritsar Road, in the Khemkaran sector of India. It had reached a village named Cheema. This village was on the Indo-Pak border. In this sector, the battle had been going on since September 6. Here, Havildar Abdul Hamid and the other soldier of '4 Grenadiers Company' were waiting to face the Pakistani Army. Brave Abdul Hamid was sitting in a jeep. He had a special gun. The Patton Tanks of the Pakistani Army were not very far from him. He could hit the tanks with his guns if he wanted to. He was a good shot but he did not want to waste his shots. He wanted to hit the tanks with each of his shots. The Pakistani tanks were very powerful and dangerous. They were approaching nearer and nearer. They were firing continually. Brave Abdul Hamid marched forward. He saw a Pakistani tank. He turned his gun and fired a shot. -

Param Vir Chakra Awardees Select Commemorative Postage Stamps on Defence Theme

Veer Gaatha Stories of Param Vir Chakra Awardees Select Commemorative Postage Stamps on Defence Theme 15 August 1976 30 July 1990 16 December 1996 16 December 1997 28 January 2000 28 January 2000 28 January 2000 28 January 2000 31 December 2003 24 October 2004 15 September 2015 15 September 2015 15 September 2015 Veer Gaatha Stories of Param Vir Chakra Awardees ISBN 978-93-5007-765-8 First Edition ALL RIGHTS RESERVED January 2016 Pausha 1937 No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise Reprinted without the prior permission of the publisher. May 2016 Jyestha 1938 This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, June 2016 Jyestha 1938 by way of trade, be lent, re-sold, hired out or otherwise disposed of without the publisher’s consent, in any form of June 2019 Jyestha 1941 binding or cover other than that in which it is published. The correct price of this publication is the price printed on this page, Any revised price indicated by a rubber stamp or PD 10T RPS by a sticker or by any other means is incorrect and should be unacceptable. © National Council of Educational Research and OFFICES OF THE PUBLICATION Training, 2016 DIVISION, NCERT NCERT Campus Sri Aurobindo Marg New Delhi 110 016 Phone : 011-26562708 108, 100 Feet Road Hosdakere Halli Extension Banashankari III Stage Bengaluru 560 085 Phone : 080-26725740 Navjivan Trust Building ` 100.00 P.O.Navjivan Ahmedabad 380 014 Phone : 079-27541446 CWC Campus Opp. -

District Census Handbook, Ghazipur, Part-XII-B, Series-25, Uttar Pradesh

\it '1 JI 0111 1991 CENSUS 1991 . »1 tsI cl J-25 SERIES-25 \3Cf1~ ~ UTTAR PRADESH ~-XII€f PART-XIIB lJlli q ~~I~~ VILLAGE & TOWNWISE m~~cp \Ji.,~IOI11 PRIMARY CENSUS ABSTRACT x=rR ~ \ii;:PIOI~1 5fC1~ffd¢1 DISTRICT CENSUS HANDBOOK Rri cYH JIf ~ 9)'( DISTRICT GHAZIPUR'· , A4~lch \Ji~JIOI~1 cwi DIRECTOR OF CENSUS OPERATIONS. urrAI~ PRADESH \3ffix m 1. Q'({II q"l1 I 2. ~ V 3. ~ q;r '1I'1Rl?l IX 4. ~ cB" '1i5ti1 'l0f ~ XX 5. ~ IJFPlol'"ll i5'R1~RtlCf>1 l)' V¥ff ~ ~ qR'II~I';[ 6. FcI~8f6lUII~Cf) Fetquft 15 7. ~ ~ IJHJIUHI x:JR 8. '!lIJflol/"iJI{);Q ~ GFPlol'"ll x:JR 31- (i)lJllfiuT-'1I'"1Rl"?l ~ ~ =1JI="iTnJIorTT:I'1:rT1 -mx 1. f1ljGI~¢ ~ ~-IJI\!SIIPI<LII 23 2. 'HljGI~¢ fclcpm ~ '1P1§I;{l 61 3. 'HljGI~¢ fclcpm ~-~ 95 4. 'HljGI~Cfj fclcpm ~-~ 123 5. 'HljGI~Cfj ~ ~-~qCf>cl) 159 6. tfljGlfllCf> fcrcm:r ~-cfi+IT 193 7. 'HljGlfllCf> fcrcf;m ~-~ 213 B. flljGlfllCf> fctqm:r ~ JI "Jjl~'< 233 9. flljGlfllCIJ fctqm:r ~-Cf>'<I"';S1 261 10. 'HljGI~CIJ fctclm;r ~ Cf>~+1I6jIG 279 11. flljGlfllCf> fctqm:r ~-61\$lillq,< 321 12. 'HljGI~¢ fctqmq- ~ sflt:UJGliSfiG 353 13. 'HljGlfll¢ fctqm:r ~-'+iq'<Cf)~&1 393 14. XiljGIf!lCf> ~ ~-\i"AIf.1;Q1 431 15. XiljGI~Cf> fctcI;m ~ ~qffl~'< 457 16. XiljGIf!lC/? fcrq;ffi ~-~ 473 17. q.:r m11 31- (ii) lJTJlT ~ qOlf'jW+1 ~ 1. fi IjG I fll Cf) fctc:f>R:r ~ =1JI=\!SInf,PI'TlirTTl 487 2. fll~~lftlcn fcrq;m ~ tJP!t:I;fJ 498 3. -

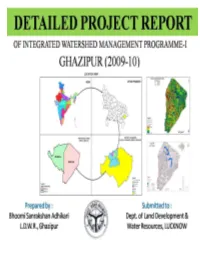

IWMP-I Project Comprising Two Micro-Watersheds of District

1 CERTIFICATE It is certified that the proposed IWMP-I project comprising Two micro-watersheds of district Ghazipur, Uttar Pradesh has been selected for its sustainable development on watershed basis under Integrated Watershed Management Programme. The land is physically available for proposed interventions and is not overlapping with any other schemes. It will be developed as per Common Guidelines for Watershed Development Project-2008, GOI, New Delhi. The significant results will be achieved through proposed interventions on soil and water conservation, ground water recharge, availability of drinking and irrigation water, agricultural production systems, livestock, fodder availability, livelihoods of asset-less, capacity building, etc. The proposed Detailed Project Report of IWMP-I for financial year 2009-10 is submitted for its implementation. Bhoomi Sanrakshan Adhikari Department of Land Development & Water Resources, Ghazipur, Uttar Pradesh 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER No. DESCRIPTIONS PAGE NO. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 4 1. INTRODUCTION AND BACKGROUND 9 2. GENERAL DESCRIPTION OF PROJECT AREA 15 3. BASELINE SURVEY 27 4. INSTITUTIONAL BUILDING AND PROJECT MANAGEMENT 44 5. MANAGEMENT / ACTION PLAN 61 6. LIVELIHOOD ACTIVITIES 65 7. CAPACITY BUILDING PLAN 85 8. PHASING OF PROGRAMME AND BUDGETING 89 9. CONSOLIDATION / WITHDRAWAL STRATEGY 93 10. EXPECTED OUTCOME 96 11. COST NORMS & DESIGN OF STRUCTURE PROPOSED 100 12. MAPS 107 13. Annexure-1 & 2 121 14. ABBRIVIATIONS/REFERENCES 158 3 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY IWMP-I Project is located in Jakhania Block of Ghazipur district, Uttar Pradesh. The Project comprises of 2 Micro-watersheds code no: 2B2B2d2a and 2B2B2e1a. The total geographical area of the project is 5082.00 ha, out of which 4304.00 ha area has been taken for treatment under Integrated Watershed Management Programme starting year 2009-10.