Urbanisation in South Africa: a Critical Review of Policy, Planning and Practice

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Marikana Exposes the Limits of the New Afro-Enthusiasm

4/27/2017 Africa at LSE – Marikana exposes the limits of the new Afroenthusiasm Marikana exposes the limits of the new Afro-enthusiasm Steve Sharra is a recent graduate of LSE’s Programme for African Leadership. In this post, he urges African governments to weigh the benefits of neoliberal economics against the widening gap of inequality it creates. As a Malawian, the 16 August Marikana Mine massacre in South Africa invokes the kinds of questions that Malawians asked on 20 July in 2011. Why did the police shoot to kill demonstrators? Was there absolutely no nonviolent action the police could have taken, other than killing so many protesters? Were the demonstrators so violent that the police had no option but to shoot to kill? On both 20 July 2011 in Malawi and 16 August 2012 in South Africa, blame has been apportioned on both sides, revealing the ideological worldviews that we use to interpret ghastly events like these. Around the world on 16 August, people’s memories went back to 21 March, 1960. On that day South African police shot and killed 69 demonstrators. As with Sharpeville, one version of events said the police had shot at peaceful, unarmed people, while another version described the demonstrators as armed and having threatened police. Striking miners gather to protest against Lonmin Photo:Siphiwe Sibeko/Reuters President Jacob Zuma cut short a trip to a SADC summit in Mozambique, and urged an end to the finger pointing to let South Africans mourn and allow a commission of inquiry to investigate what really happened. -

Ncta Map 2017 V4 Print 11.49 MB

here. Encounter martial eagles puffed out against the morning excellent opportunities for river rafting and the best wilderness fly- Stargazers, history boffins and soul searchers will all feel welcome Experience the Northern Cape Northern Cape Routes chill, wildebeest snorting plumes of vapour into the freezing air fishing in South Africa, while the entire Richtersveld is a mountain here. Go succulent sleuthing with a botanical guide or hike the TOURISM INFORMATION We invite you to explore one of our spectacular route and the deep bass rumble of a black- maned lion proclaiming its biker’s dream. Soak up the culture and spend a day following Springbok Klipkoppie for a dose of Anglo-Boer War history, explore NORTHERN CAPE TOURISM AUTHORITY Discover the heart of the Northern Cape as you travel experiences or even enjoy a combination of two or more as territory from a high dune. the footsteps of a traditional goat herder and learn about life of the countless shipwrecks along the coast line or visit Namastat, 15 Villiers Street, Kimberley CBD, 8301 Tel: +27 (0) 53 833 1434 · Fax +27 (0) 53 831 2937 along its many routes and discover a myriad of uniquely di- you travel through our province. the nomads. In the villages, the locals will entertain guests with a traditional matjies-hut village. Just get out there and clear your Traveling in the Kalahari is perfect for the adventure-loving family Email: [email protected] verse experiences. Each of the five regions offers interest- storytelling and traditional Nama step dancing upon request. mind! and adrenaline seekers. -

Traffic Impact Assessment

Project name: Concentrated 4 March 2016 Revision: 0 Solar Power Plant on the Farm Reference: Project No Sand Draai 391, Northern Cape 112399 Traffic Impact Assessment Client: Royal Haskoning DHV Document control record Document prepared by: AURECON Ground Floor, West Building, Milkwood Office Park Cnr Umhlanga Rocks & Douglas Saunders Drive La Lucia Ridge, 4019 Tel: +27 31 575 5500 Fax: +27 86 244 9177 Email: [email protected] Web: aurecongroup.com A person using Aurecon documents or data accepts the risk of: a) Using the documents or data in electronic form without requesting and checking them for accuracy against the original hard copy version. b) Using the documents or data for any purpose not agreed to in writing by Aurecon. Document control Report title TIA for the Concentrated Solar Power Plant on the Farm Sand Draai 391, Northern Cape Document ID Project number Project No 112399 File path P:\Projects\112399 Sand Draai EIA Solar Power Plants\03 PRJ Del\6 REP Client Client: Royal Haskoning Client contact Johan Blignaut DHV Re Date Revision details/status Author Reviewer Verifier Approver v (if required) 0 4 March 2016 Final Rishaal Rishaal M van Sahadew Sahadew Tonder Current revision 0 Approval Author signature Approver signature Name Name Title Title Project Project No 112399 File TIA SAND DRAAI CSP 4 March 2016 Revision 0 Project name: Concentrated Solar Power Plant on the Farm Sand Draai 391, Northern Cape Date 4 March 2016 Reference Project No 112399 Revision 0 AURECON Ground Floor, West Building, Milkwood Office Park Cnr Umhlanga Rocks & Douglas Saunders Drive La Lucia Ridge, 4019 Tel: +27 31 575 5500 Fax: +27 86 244 9177 Email: [email protected] Web: aurecongroup.com Project Project No 112399 File TIA SAND DRAAI CSP 4 March 2016 Revision 0 Contents 1 Introduction 1 1.1 Objectives of the Specialist Traffic and Transportation Study 2 1.2 Project Description 3 1.3 Description of the Study Area 4 2 OVERVIEW OF THE SURROUNDING ROAD NETWORK 5 2.1 General Description of the Surrounding Road Network. -

Report Ladybrand Maseru N8 Enviro 2013

3 JUNE 2013 FIRST PHASE ARCHAEOLOGICAL & HERITAGE ASSESSMENT OF THE PROPOSED REALIGNMENT OF THE N8 NATIONAL ROAD BETWEEN THE R26/N8 INTERSECTION & MASERU BRIDGE BORDER POST, LADYBRAND, FREE STATE EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The N8 national road provides a vital link between Lesotho and South Africa. To improve the road connection, the South African National Road Agency LTD, is planning the realignment of a section of the N8 Ladybrand and the Maseru Bridge Border Post. The realignment will start from the existing N8/R26 intersection and will follow the S836 gravel road to tie in along the N8 between Ladybrand and the Maseru Bridge. The length of the realignment is approximately 13 kilometres. The whole region is part of intensive agricultural land, which has been cultivated for decades. Scars left by road building are also visible. No archaeological, cultural or any historical remains were found along the route. It is clear that the new developments will have no impact on any cultural heritage and historical remains in the area. Further planning of the proposed project may continue, and no mitigation measures will be needed. INTRODUCTION & DESCRIPTION Enviroworks Environmental Consultants from Bloemfontein had been commissioned by the National Roads Agency to compile the Environmental Impact Assessment for the proposed developments. 2 A list of the names and particulars of effected farm owners is enclosed herewith (See ANNEXURE 1). Scope and Limitations SANRAL is planning the realignment of a section of the N8 between the N8/R26 intersection near Ladybrand and the Maseru Bridge Border Post. The relocation of the road will start from the existing N8/R26 intersection and will follow the S836 gravel road to link-up with the N8 between Ladybrand and the Maseru Bridge. -

Narratives of Contradiction: South African Youth and Post-Apartheid

Narratives of Contradiction: South African Youth and Post-Apartheid Governance By Elene Cloete Ó 2017 Submitted to the graduate degree program in Anthropology and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy ________________________________ Chairperson John M. Janzen, Ph.D. ________________________________ Hannah E. Britton, Ph.D. ________________________________ Donald D. Stull, Ph.D. ________________________________ Elizabeth L. MacGonagle, Ph.D. ________________________________ Byron Caminero-Santangelo, Ph.D. Date Defended: May 17, 2017 The Dissertation Committee for Elene Cloete certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Narratives of Contradiction: South African Youth and Post-Apartheid Governance _______________________________ Chairperson John M. Janzen Date approved: May 17, 2017 ii Abstract South Africa’s heralded democratic transition digressed from its 1994 euphoric optimism to a current state of public discontent. This stems from rising unemployment, persistent structural inequality, and a disappointment in the African National Congress-led government’s inability to bring true social and economic transformation to fruition. While some scholars attribute this socioeconomic and political predicament to the country’s former regimes, others draw close correlations between the country’s post-apartheid predicament, ANC leadership, and the country’s official adoption of neoliberal economic policies in 1996. Central to this post-euphoric moment is the country’s Born-Free generation, particularly Black youth, coming of political age in an era of supposed political freedom, social equality, and economic opportunities. But recent student movements evidence young people’s disillusionment with the country’s democratic transition. Such disillusionment is not unfounded, considering the 35% youth unemployment rate and questionable standards in primary education. -

The Role of Sustainable Planning in Order to Accommodate Informal Brickyards in the Integrated Development Plan of the Mangaung Municipality

G.M. Steenkamp & J.J. Steÿn, Int. J. Sus. Dev. Plann. Vol. 1, No. 4 (2006) 443–450 TO CONTROL OR NOT TO CONTROL: THE ROLE OF SUSTAINABLE PLANNING IN ORDER TO ACCOMMODATE INFORMAL BRICKYARDS IN THE INTEGRATED DEVELOPMENT PLAN OF THE MANGAUNG MUNICIPALITY G.M. STEENKAMP & J.J. STEŸN Department of Urban and Regional Planning, University of the Free State, Bloemfontein, South Africa. ABSTRACT During 1994 and 1999, the Bloemfontein Municipality amalgamated with five other municipalities to form the Mangaung Municipality. The Mangaung Municipality now has a population of approximately 740,000 and covers an area of 6,363 km2. Some areas are totally urban; while in others, people live in informal settlements. The unemployment rate is 35%, but in some areas it has risen to as high as 48%. Poor people in the city cannot afford to buy burnt bricks from the major suppliers of bricks. Therefore, informal brickyards were established all over the areas where clay and/or water were available. These brickyards are now producing good homemade burnt bricks and are creating jobs in a sea of unemployment. However, the problem is that from a planning and sustainability viewpoint, all is not well.Although the location of the brickyards has brought about a saving in costs related to the transportation of bricks from the formal brickyards, of which the nearest is 300 km away, the coal- burning activities of the informal brickyards create air pollution. Furthermore, no prior environmental impact studies were carried out before deciding on the location of the brickyards. Most of them have been established haphazardly in any available spot. -

Griekwastad Tourism Brochure.Pdf

Kontakbesonderhede / Contact details Griekwastad / Giquatown Uitgegee deur / Published by Mary Moffat Museum Griekwastad / Griquatown Ontwerp & uitleg / Designed by Hospitality@UrDoor PTY Ltd Tel: 083 610 7899 Fotos, inligting en advertensies / Photos, information and advertisements Museum, besighede en inwoners Museum, businesses & residents Hospitality@UrDoor PTY Ltd Tel: 083 610 7899 Digital Action, Paarden Eiland 021 511 9703 [email protected] Griekwastad / Griquatown Op reis na / En-route to Griekwastad / Griquatown GPS 28 51' 00'' 23 15' 00'' Die Korana-woord vir water is T!ama (uitroepteken, wat klapklank aandui) en ‘n waterryke vallei heet vanaf / from Kimberley T!ari (karréép), volgens WJ Burchell 1812. Vandaar N8– 152 km’s die naam Karrikamma, Griekwastad se eerste naam. Dit beteken dus dieselfde as Klaarwater (wat vanaf / from Upington N14- 284 km’s helder water beteken), wat tot 1813 gebruik is. Toe het sendeling John Campbell het die naam Omliggende dorpe / Surrounding towns verander na Griquatown / Griekwastad. Die agtervoegsel –kwa /qua beteken “seuns of manne Postmasburg– 68.7 km’s van”. Die naam Griekwastad beteken “seuns of manne van Chariguri of Grigri”. Douglas– 82.9 km’s Olifantshoek– 130 km’s Groblershoop– 138 km’s Kuruman– 194 km’s Bloemfontein– 314 km’s GRIEKWASTAD GRIQUATOWN Griekwastad is 'n dorp in die Noord- Griquatown is a town in the Northern Kaap, Suid-Afrika. Die N8 nasionale pad Cape province in South Africa. The N8 gaan deur Griekwastad. Kimberley is National Road runs through the town ongeveer 150 km oos van Griekwastad. and Kimberley is approximately 150 km’s east of Griquatown. Adam Kok II, 'n bevryde slaaf, het sy groep volgelinge (hulle is toe nog nie Adam Kok II, a freed slave, led his Griekwas genoem nie, en het uit talle followers from Piketberg to the current nasies bestaan, bv drostermatrose en Griquatown area. -

36740 16-8 Road Carrier Permits

Government Gazette Staatskoerant REPUBLIC OF SOUTH AFRICA REPUBLIEK VAN SUID-AFRIKA August Vol. 578 Pretoria, 16 2013 Augustus No. 36740 PART 1 OF 2 N.B. The Government Printing Works will not be held responsible for the quality of “Hard Copies” or “Electronic Files” submitted for publication purposes AIDS HELPLINE: 0800-0123-22 Prevention is the cure 303563—A 36740—1 2 No. 36740 GOVERNMENT GAZETTE, 16 AUGUST 2013 IMPORTANT NOTICE The Government Printing Works will not be held responsible for faxed documents not received due to errors on the fax machine or faxes received which are unclear or incomplete. Please be advised that an “OK” slip, received from a fax machine, will not be accepted as proof that documents were received by the GPW for printing. If documents are faxed to the GPW it will be the senderʼs respon- sibility to phone and confirm that the documents were received in good order. Furthermore the Government Printing Works will also not be held responsible for cancellations and amendments which have not been done on original documents received from clients. CONTENTS INHOUD Page Gazette Bladsy Koerant No. No. No. No. No. No. Transport, Department of Vervoer, Departement van Cross Border Road Transport Agency: Oorgrenspadvervoeragentskap aansoek- Applications for permits:.......................... permitte: .................................................. Menlyn..................................................... 3 36740 Menlyn..................................................... 3 36740 Applications concerning Operating Aansoeke -

2018 INTEGRATED REPORT Volume 1

2018 INTEGRATED REPORT VOLUME 1 Goals can only be achieved if efforts and courage are driven by purpose and direction Integrated Report 2017/18 The South African National Roads Agency SOC Limited Reg no: 1998/009584/30 THE SOUTH AFRICAN NATIONAL ROADS AGENCY SOC LIMITED The South African National Roads Agency SOC Limited Integrated Report 2017/18 About the Integrated Report The 2018 Integrated Report of the South African National Roads Agency (SANRAL) covers the period 1 April 2017 to 31 March 2018 and describes how the agency gave effect to its statutory mandate during this period. The report is available in printed and electronic formats and is presented in two volumes: • Volume 1: Integrated Report is a narrative on major development during the year combined with key statistics that indicate value generated in various ways. • Volume 2: Annual Financial Statements contains the sections on corporate governance and delivery against key performance indicators, in addition to the financial statements. 2018 is the second year in which SANRAL has adopted the practice of integrated reporting, having previously been guided solely by the approach adopted in terms of the Public Finance Management Act (PFMA). The agency has attempted to demonstrate the varied dimensions of its work and indicate how they are strategically coherent. It has continued to comply with the reporting requirements of the PFMA while incorporating major principles of integrated reporting. This new approach is supported by the adoption of an integrated planning framework in SANRAL’s new strategy, Horizon 2030. In selecting qualitative and quantitative information for the report, the agency has been guided by Horizon 2030 and the principles of disclosure and materiality. -

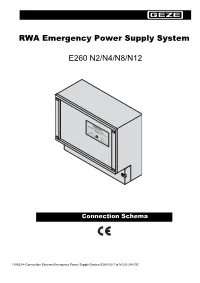

RWA Emergency Power Supply System E260 N2/N4/N8/N12

Emergency Power Supply System E260 N2/N4/N8/N12 RWA Notstromsteuerzentrale Emergency Power Control System E 260 N grn OK grünrot OK green Störung gelbrot blinkend Fault yellow Netzausfall gelb blinkend Power outage yellow flashing Connection Schema 118533-4 Connection Schema Emergency Power Supply System E260 N2/1 to N12/2-24V DC Contents 1. Short description...............................................................................................................................................................2 2. Layout plan ..........................................................................................................................................................................3 3.1 Mains connection ...........................................................................................................................................................4 3.2 Connection of the battery ...........................................................................................................................................4 3.3 Connection of smoke and heat difference sensor ...........................................................................................4 3.4 Operation without smoke or heat difference senosr.......................................................................................4 3.5 Connection of SHE switch FT4/24V DC - VdS ....................................................................................................5 3.6 Connection of fire alarm system (BMS) / remote trip release .....................................................................5 -

Centre Details

Centre details Opening date: September 2016 Size: 21 000m2 Owner: Stanlib Botshabelo Mall, because of its location at the main and only entrance to Botshabelo and the proximity to the N8 which links Bloemfontein to Thaba Nchu, it will act as a regional centre to the entire area. A brief overview via google earth shows the vastness of the Botshabelo area and the substantial number of residents that the Mall will serve. The response from the nationals has been very strong. The centre will be anchored by two Supermarkets, Shoprite and Pick n Pay. There will be an exceptionally strong fashion component with The Foschini group with 5 brands, Truworths with 2 brands, Pepkor group and Woolworths. Furniture will be represented by Morkels, Ok Furniture and Lewis. We also have board approval from Cashbuild. Tenant Mix SHOP AREA Pick n Pay 2 000 Pick n Pay (Liquor) 300 Woolworths 800 Roots 540 Cashbuild 1 330 Clicks 550 Truworths 700 Identity 300 Foschini 300 Markham 200 Totalsports 220 Exact 300 Fashion Express 249 Rage 98 Sheet Street 150 OK Furnishers 686 Shoprite Liquor 160 Shoprite 2850 Pep Cell - Pepkor 45 Hungry Lion 160 Chesanyama 100 Alpha Pharm 187 Capitec Bank 242 Old Mutual Bank 143 Pep 450 Real Fish and Chips 102 Lewis 216 Morkels. 431 Site Location The site is located on the corner of Main Road and a national highway, the N8. Main road is the key feeder road into and out of Botshabelo (from the N8) while the N8 is the main transport route between Maseru (Lesotho), Bloemfontein and Kimberley. -

£¤N6 £¤N1 £¤N8 £¤N1 £¤N8 £¤N8

WARD DELIMITATION 2021 Mangaung Metropolitan Municipality (MAN) WAR D : 27 22630238 109 R30 Ward 9 DRAFT WARDS ST 22630148 22190015 76 Ward 2 994 Bofulo Kgalala 22120232 22120074 139 22080013 N1 ¤£ Ward 3 239 245 22080046 22630272 Modutung 236 Municipal Demarcation Board Ward 44 115 Tel: (012) 342 2481 22120063 Fax: (012) 342 2480 email: [email protected] 272 web: www.demarcation.org.za 22080057 Ward 27 Morago 613 22120210 Houtnek Kenilworth AH 254 Ü Spitskop Village 21861873 M30 The ST 22120052 745 Kloof Ward 48 R700 21860276 Ward 17 216 RaytonST M30 22120119 Legend Rooidam SH ST 1557 Middeldeel Knocknacree SHLilyvale SH Deals Gift AH 223 R64 Heliconhoogte Olive Hill SH ST Hillsboro Deales Gift Mockes Dam Pentagon Park Bloemfontein Airport Spitshop SH Heuwelsig Bayswater 22120209 Local Municipalities Kiepersol Merino Ratabane Spitskop Noordhoek 213 Tempe Dan Waverley Ward 47 22120186 Paradys Brandwag Pienaar Naval Hill Estoire AH Bloemspruit 141 Wards M14 Bob ST Park WestWestdene Arboretum Airforce Base Bloemfontein Central Hilton Rodgers Park Feloane Kwaggafontein Oos Einde 22080248 22080080 Tiger River Ward 41 Universitas ¤£N8 21861895 22120333 Voting Districts Wilgehof 21860984 797 300 252 22120197 Oranjesig 474 22120108 Gardenia Willows 1384 Bloemdustria N8 Langenhovenpark White City Potsane 220 253 National Roads ¤£ Park Hospitalpark NONE Heidedal Bochabela Kwaggafontein General Opkoms North Shannon SH SH Fichardt Park M30 Main Roads De Wet ST Batho Joe Bloemside Phase 1 Pellissier Fleurdal Peter PPehtaerh aSmweanrtg PhaSsleo