An Experimental Representation of Natural Landscapes Through the Utilization of Analog Film Techniques

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

AC Issue49 March2011.Pdf

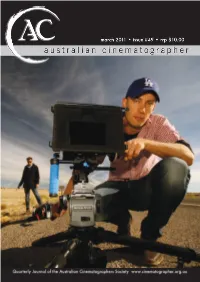

ac_issue#49.indd 1 22/03/11 2:14 PM Complete 35mm Package You thought you couldn’t afford film anymore... ...think again. Complete 35mm is the 35mm film and processing package from FUJIFILM / Awesome Support and Deluxe. Designed to offer the flexibility and logistical benefits of the film origination at a preferential price. The package includes: • 35mm FUJIFILM motion picture film stock • 35mm negative developing at Deluxe 400’ roll* 1000’ roll* $424 ex gst $1060 ex gst *This special package runs from 1st December 2010 to 31st January 2011 and it is open to TVC production companies for TVC / Rock clips / Web idents etc. Package applies to the complete range of FUJIFILM 35mm film in all speeds. No minimum or maximum order. Brought together by AUSTRALIA Contact: Ali Peck at Awesome Support 0411 871 521 [email protected] Jan Thornton at Deluxe Sydney (02) 9429 6500 [email protected] or Ebony Greaves at Deluxe Melbourne (03) 9528 6188 [email protected] ac_issue#49.indd 2 22/03/11 2:15 PM Not your average day at the supermarket. It’s Bait in 3D. Honestly, it would have been very difficult to make this movie without Panavision. Their investment and commitment to 3D technologies is a huge advantage to filmmakers. Without a company the size and stature of Panavision behind these projects they would be very difficult to achieve. Ross Emery ACS Shooting in 3D is a complex and challenging undertaking. It’s amazing how many people talk about being able to do it, but Panavision actually knows how to make it happen. -

Certain Women

CERTAIN WOMEN Starring Laura Dern Kristen Stewart Michelle Williams James Le Gros Jared Harris Lily Gladstone Rene Auberjonois Written, Directed, and Edited by Kelly Reichardt Produced by Neil Kopp, Vincent Savino, Anish Savjani Executive Producers Todd Haynes, Larry Fessenden, Christopher Carroll, Nathan Kelly Contact: Falco Ink CERTAIN WOMEN Cast (in order of appearance) Laura LAURA DERN Ryan JAMES Le GROS Fuller JARED HARRIS Sheriff Rowles JOHN GETZ Gina MICHELLE WILLIAMS Guthrie SARA RODIER Albert RENE AUBERJONOIS The Rancher LILY GLADSTONE Elizabeth Travis KRISTEN STEWART Production Writer / Director / Editor KELLY REICHARDT Based on stories by MAILE MELOY Producers NEIL KOPP VINCENT SAVINO ANISH SAVJANI Executive Producers TODD HAYNES LARRY FESSENDEN CHRISTOPHER CARROLL NATHAN KELLY Director of Photography CHRISTOPHER BLAUVELT Production Designer ANTHONY GASPARRO Costume Designer APRIL NAPIER Casting MARK BENNETT GAYLE KELLER Music Composer JEFF GRACE CERTAIN WOMEN Synopsis It’s the off-season in Livingston, Montana, where lawyer Laura Wells (LAURA DERN), called away from a tryst with her married lover, finds herself defending a local laborer named Fuller (JARED HARRIS). Fuller was a victim of a workplace accident, and his ongoing medical issues have led him to hire Laura to see if she can reopen his case. He’s stubborn and won’t listen to Laura’s advice – though he seems to heed it when the same counsel comes from a male colleague. Thinking he has no other option, Fuller decides to take a security guard hostage in order to get his demands met. Laura must act as intermediary and exchange herself for the hostage, trying to convince Fuller to give himself up. -

New Films from Germany

amherstcinema FEB - APR 28 Amity St. Amherst, MA 01002 • www.amherstcinema.org • 413.253.2547 2020 See something different! In addition to the special events in this newsletter, Amherst Cinema shows current-release film on four screens every day. Visit amherstcinema.org and join our weekly e-newsletter for the latest offerings. films of Kelly Reichardt In anticipation of the March 2020 opening of her new movie, FIRST COW, Amherst Cinema is pleased to present four films from the back catalog of director Kelly Reichardt. Reichardt's dramas are small-scale symphonies; alchemical transmogrifications of the ordinary into gripping cinematic experiences. Often collaborating with the same creatives across multiple pictures, such as actor Michelle Williams and writer Jonathan Raymond, Reichardt's films turn the WENDY AND LUCY lens on those in some way at the margins of American communities. Be it a woman living out of her car in WENDY AND LUCY, a group of lost 1840s pioneers in MEEK'S CUTOFF, a reclusive ranch hand in CERTAIN WOMEN, or a hand-to-mouth ex-hippie in OLD JOY, Reichardt's characters, regardless of life circumstances, are deeply and richly human. There may be no other living filmmaker who so fully realizes Roger Ebert's assertion that "movies are the most powerful empathy machine in all the arts." All of which is to say nothing of her films' painterly cinematography, naturalistic and immersive sound design, and Reichardt's knack of scouting the perfect space for every scene, often in the wilds of the Pacific Northwest. Reichardt and her work have been honored at the Cannes Film Festival, the Venice Film Festival, the BFI MEEK'S CUTOFF London Film Festival, the Film Independent Spirit Awards, and more. -

Night Moves Instrueret Og Skrevet Af Kelly Reichardt

ANGEL FILMS PRÆSENTERER Night Moves Instrueret og skrevet af Kelly Reichardt 112 minutter Kontakt:(Peter(Sølvsten(Thomsen,([email protected]( 1 Night Moves Dansk synopsis: En spændingsfyldt fortælling om de tre passionerede miljøaktivister, Josh (Jesse Eisenberg), Dena (Dakota Fanning) og Harmon (Peter Sarsgaard), der sammen planlægger en bombeaktion mod en dæmning. Aktionen lykkes, men ikke uden uforudsete konsekvenser – konsekvenser som skal vise sig at blive skæbnesvanger for de tre aktivister. Josh, Dena og Harmon vender tilbage til deres hverdag i forsøget på at holde lav profil, men begynder hurtigt at mærke det psykiske pres af deres store hemmelighed. Efterhånden som paranoia og mistillid kryber ind i de sammensvornes hoveder, begynder idealismens skyggesider at vise sig. Gennem Kelly Reichardts særegne stil og atmosfære, stiller NIGHT MOVES skarpt på spørgsmålet om, hvorvidt terrorhandlinger kan retfærdiggøres, så længe bevæggrunden herfor er sympatisk, eller om al terror leder til umoralsk fanatisme? Kontakt:(Peter(Sølvsten(Thomsen,([email protected]( 2 NIGHT MOVES ABOUT THE STORY Kelly Reichardt’s suspense thriller NIGHT MOVES follows three passionate environmentalists whose homegrown plot to Blow up a controversial dam unravels into a journey of douBt, paranoia and unintended consequences. Set against the ravishing, threatened natural Beauty of Oregon, the film tracks step-By- relentless-step as quiet organic farmer Josh (Jesse EisenBerg, THE SOCIAL NETWORK), high society dropout Dena (Dakota Fanning, WAR OF THE WORLDS, the TWILIGHT saga) and adrenaline-driven ex-Marine Harmon (Peter Sarsgaard, BLUE JASMINE, “The Killing”) prepare, carry out and then experience the shocking fallout of what they hoped would Be an attention-grabBing act of sabotage. -

Crystal Moselle

un film de – een film van CRYSTAL MOSELLE USA – 105 MIN. SYNOPSIS NL Camille is 18 jaar en dol op skateboarden. Dat vindt haar moeder maar niks, en na een blessure moet Camille beloven om nooit meer te skaten. Geen denken aan - de passie is te groot! Via Instagram komt Camille in contact met ‘The Skate Kitchen’, meisjes die stuk voor stuk ‘leven om te skaten’. Ze voelt zich meteen welkom bij de groep en dankzij hun wilde levensstijl gaat er een nieuwe wereld voor haar open. Wanneer haar moeder gaat dwarsliggen, loopt Camille weg van huis en trekt in bij een van haar nieuwe vriendinnen. Tot de liefde hun fragiele band onder druk zet. FR A New-York, la vie de Camille, une adolescente solitaire et introvertie va radicalement changer en intégrant un groupe de jeunes filles skateuses appelé Skate Kitchen. Cette bande éprise de liberté et sa rencontre avec un jeune skateur énigmatique vont l’éloigner de sa mère avec qui elle s’entend de moins en moins. ENG A teen girl gets on the ride of her life when she joins all-girl New York skateboard collective Skate Kitchen and falls for a mysterious guy in the scene. INTERVIEW WITH DIRECTOR CRYSTAL MOSELLE Skate Kitchen is a real skateboarding collective, and the cast is made up of real skateboarders. How did you meet them? I was on the train and I was listening to them just chat, and they were super interesting and they had skateboards, and I asked them, “Would you guys want to do like a video project, something?” We exchanged numbers and when we met up we just started hanging out and chatting. -

Eumig M-1000 Service Manual

Eumig M-1000 Service Manual Bell & Howell - Eumig - Elmo - Sankyo - Kodak - Sears - Minolta I Only Service The Projectors I Refurbish And Sell Myself. I'm sure there are some good dual machines but I just prefer not to have to deal with them because of All books below are the instruction book, unless noted as being repair or service manuals. Manual Library / Dynacord Recently Viewed. Denon AVP-A1HD, TEAC X-700R, Philips N4422, Eumig M-1000, JVC RX-E12. Eumig FL-1000 Thread. Service Manual (top Qualität): @Matthias M: Die Schalterposition "-9dB" müßtest Du an Deinem Deck ja dann auch haben, es sei. Find great deals on eBay for Eumig Film Projector in Slide and Movie Manual (8) Vintage EUMIG WIEN Imperial P8 Cine 8mm Home MOVIE Projector SPARES OR REPAIR Instructions cine projector Eumig mark M - CD/Email. Audio-Hifi service manuals and schematics - Electronics Service & Repair Forum. ECLER DPA600 DPA1000 DPA1400 DPA2000 AMPLIFIERS, ECLER DPC215 DPC118 SPEAKER EFIR-67 OROSZ RADIO SCH, EFIR-M OROSZ RADIO SCH EUMIG 1133 TUBES RADIO SCH, EUMIG 1143 RECEIVER SCH. PHILIPS MAG01 Chassis Service Manual English EUMIG MARK S 710D Quick Start Guide French SIEMENS MAMMOMAT 1000 Service Manual English Eumig M-1000 Service Manual Read/Download Auctions, Sources, Manuals, Parts & Acc. For 8mm Movie Projectors. 2pcs RM109A EJV 21V 150W - Mille Luce Fiber Optic Illuminator M1000 - Mitutoyo Dual - Efos 3040 - Eumig M25 Deluxe , Mark S705, Polylite I II, Polysteril Polisterile II. 40S OWNERS MANUAL. Manual for 1-31- TAITO.Many of our items do not include an owners manual any more. -

Film Matters Magazine

5/30/2020 The 50-Year Road Trip: Kelly Reichardt on Night Moves - MovieMaker Magazine MOVIEMAKING MOVIE NEWS FESTIVALS LATEST ISSUE PODCASTS The 50-Year Road Trip: Kelly Reichardt on Night Moves Latest DIRECTING MOVIE NEWS By Film Distribution Vet Liz Josh Ralske Manashil Explores the Future Published on June 20, 2014 of a Post-Pandemic Film Industry SHARE BY LIZ MANASHIL MAY 29, 2020 TWEET COMMENT The multi- award- winning Kelly Reichardt has produced work of such MOVIE NEWS routinely Everything You Need to Know superb quality About HBO Max — Including that it eluded Why It’s Not Available on Roku me until or Amazon Fire TV Sponsored by Sperry The 50-Year Road Trip: Kelly Reichardt on Night Moves Introducing the PLUSHWrecenAVEtly Collection how BY LOREE SEITZ MAY 29, 2020 far outside SHARE TWEOurET all-new PLUSHWAVE technology puts ultra-cushioning on your feet. A light fit design with flex grip stands up to LEARN MORE twhateverhe the day brings your way. https://www.moviemaker.com/the-50-year-road-trip-kelly-reichardt-on-night-moves/ 1/41 5/30/2020 The 50-Year Road Trip: Kelly Reichardt on Night Moves - MovieMaker Magazine mainstream she’s considered. TO TOP She’s justly revered by discerning ¤lm critics and festival programmers, and these days, thanks in part to Michelle Williams’ outstanding work in Wendy & Lucy Instagram and Meek’s Cuto¡, A-list actors are eager to work with her. And yet, as you’ll read below, there’s a disheartening precariousness to her ¤lmmaking career. Will Night Moves change that? It’s another thought- provoking, engaging, and beautifully rendered ¤lm, and features wonderfully true- to-life performances from Jesse Eisenberg, Dakota Fanning, and Peter Sarsgaard. -

International & Festivals

COMPANY CV – INTERNATIONAL & FESTIVALS INTERNATIONAL CAMPAIGNS / JUNKETS / TOURS (selected) Below we list the key elements of the international campaigns we have handled, but our work often also involves working closely with the local distributors and the film-makers and their representatives to ensure that all publicity opportunities are maximised. We have set up face-to-face and telephone interviews for actors and film-makers, working around their schedules to ensure that the key territories in particular are given as much access as possible, highlighting syndication opportunities, supplying information on special photography, incorporating international press into UK schedules that we are running, and looking at creative ways of scheduling press. THE AFTERMATH / James Kent / Fox Searchlight • International campaign support COLETTE / Wash Westmoreland / HanWay Films • International campaign BEAUTIFUL BOY / Felix van Groeningen / FilmNation • International campaign THE FAVOURITE / Yorgos Lanthimos / Fox Searchlight • International campaign support SUSPIRIA / Luca Guadagnino / Amazon Studios • International campaign LIFE ITSELF / Dan Fogelman / FilmNation • International campaign DISOBEDIENCE / Sebastián Lelio / FilmNation • International campaign THE CHILDREN ACT / Richard Eyre / FilmNation • International campaign DON’T WORRY, HE WON’T GET FAR ON FOOT / Gus Van Sant / Amazon Studios & FilmNation • International campaign ISLE OF DOGS / Wes Anderson / Fox Searchlight • International campaign THREE BILLBOARDS OUTSIDE EBBING, MISSOURI / -

Meek's Cutoff

Miranda Revue pluridisciplinaire du monde anglophone / Multidisciplinary peer-reviewed journal on the English- speaking world 18 | 2019 Guerre en poésie, poésie en guerre Neo Frontier Cinema: Rewriting the Frontier Narrative from the Margins in Meek’s Cutoff (Kelly Reichardt, 2010), Songs My Brother Taught Me (Chloe Zhao, 2015) and The Rider (Chloe Zhao, 2017) Hervé Mayer Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/miranda/16672 DOI: 10.4000/miranda.16672 ISSN: 2108-6559 Publisher Université Toulouse - Jean Jaurès Electronic reference Hervé Mayer, “Neo Frontier Cinema: Rewriting the Frontier Narrative from the Margins in Meek’s Cutoff (Kelly Reichardt, 2010), Songs My Brother Taught Me (Chloe Zhao, 2015) and The Rider (Chloe Zhao, 2017)”, Miranda [Online], 18 | 2019, Online since 16 April 2019, connection on 16 February 2021. URL: http://journals.openedition.org/miranda/16672 ; DOI: https://doi.org/10.4000/miranda.16672 This text was automatically generated on 16 February 2021. Miranda is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Neo Frontier Cinema: Rewriting the Frontier Narrative from the Margins in Mee... 1 Neo Frontier Cinema: Rewriting the Frontier Narrative from the Margins in Meek’s Cutoff (Kelly Reichardt, 2010), Songs My Brother Taught Me (Chloe Zhao, 2015) and The Rider (Chloe Zhao, 2017) Hervé Mayer 1 The myth of the American frontier has provided the United States with a national mythology since the late 19th century, and has been explored most directly on screen in the genre of the Western.1 According to this mythology, the frontier is a cultural metaphor designating the meeting point between civilized territories and the savage wilderness beyond. -

Calgary's East Asian Amateur Film Heritage

University of Calgary PRISM: University of Calgary's Digital Repository Graduate Studies The Vault: Electronic Theses and Dissertations 2020-01-20 Calgary’s East Asian Amateur Film Heritage Manabat, Sheena Rosalia Manabat, S. R. (2020). Calgary’s East Asian Amateur Film Heritage (Unpublished master's thesis). University of Calgary, Calgary, AB. http://hdl.handle.net/1880/111554 master thesis University of Calgary graduate students retain copyright ownership and moral rights for their thesis. You may use this material in any way that is permitted by the Copyright Act or through licensing that has been assigned to the document. For uses that are not allowable under copyright legislation or licensing, you are required to seek permission. Downloaded from PRISM: https://prism.ucalgary.ca UNIVERSITY OF CALGARY Calgary’s East Asian Amateur Film Heritage by Sheena Rosalia Manabat A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS GRADUATE PROGRAM IN COMMUNICATION AND MEDIA STUDIES CALGARY, ALBERTA JANUARY, 2020 © Sheena Rosalia Manabat 2020 Abstract This study explores the localized histories and identities of Asian Calgarians by examining their home movies, asking broadly: how are the visual histories of Calgary and its Asian immigrant population reflected in home movies? The project draws on earlier work from amateur cinema and film studies discourse and calls attention to the visual histories of four ethnic groups and the meanings behind their home movie making practices. Findings include the stories of the individuals and families, commonalities between similar projects, themes uncommon in existing home movie literature, and subjective images imbued with history and culture. -

To Download Press Cv

CONSULTANTS Launched in early 2010, WOLF is a boutique PR and Marketing firm specialised in helping filmmakers effectively communicate and achieve their vision. Through many years experience working for sales agents and producers, launching hundreds of films, we understand the demands of the market and offer an intelligent, fast, no-nonsense creative service. In our fragmented industry we‘re here to help join the dots. Marketing and communications are an integral part of the storytelling process, and our approach encompasses the entire production cycle: from overcoming initial obstacles to getting a new project noticed to preparing completed films for launch at major international film festivals. What‘s unique about WOLF is that we‘re hands-on designers, marketing consultants and international publicists all rolled into one, with an intimate knowledge of all the major festivals and markets. Our expertise and flexibility help directors, producers, sales agents and other partners around the world create effective strategies tailored to each project‘s needs, giving the film the best possible start on the way to finding its audience. Recent highlights of WOLF‘s slate as International Publicists include UNDINE by Christian Petzold (Silver Bear for Best Actress, Berlin 2020), MARTIN EDEN by Pietro Marcello (Platform Prize, TIFF 2019 & Coppa Volpi, Venice 2019), BABYTEETH by Shannon Murphy (Marcello Mastroianni Award, Venice 2019), THE CLIMB by Michael Angelo Covino, (Jury Coup de Coeur, Cannes Un Certain Regard 2019), SO LONG, MY SON by Wang Xiaoshuai (Silver Bears for Best Actor & Best Actress, Berlin 2019), BORDER by Ali Abbasi (Un Certain Regard Prize, Cannes 2018), WOMAN AT WAR by Benedikt Erlingsson (SACD Award, Cannes Critics‘ Week 2018), TOUCH ME NOT by Adina Pintilie (Golden Bear & Best First Feature, Berlin 2018), CUSTODY by Xavier Legrand (Best Director & Best First Feature, Venice 2017) and VR projects by Baobab Studios and director Eric Darnell (MADAGASCAR). -

Following Is a Listing of Public Relations Firms Who Have Represented Films at Previous Sundance Film Festivals

Following is a listing of public relations firms who have represented films at previous Sundance Film Festivals. This is just a sample of the firms that can help promote your film and is a good guide to start your search for representation. 11th Street Lot 11th Street Lot Marketing & PR offers strategic marketing and publicity services to independent films at every stage of release, from festival premiere to digital distribution, including traditional publicity (film reviews, regional and trade coverage, interviews and features); digital marketing (social media, email marketing, etc); and creative, custom audience-building initiatives. Contact: Lisa Trifone P: 646.926-4012 E: [email protected] www.11thstreetlot.com 42West 42West is a US entertainment public relations and consulting firm. A full service bi-coastal agency, 42West handles film release campaigns, awards campaigns, online marketing and publicity, strategic communications, personal publicity, and integrated promotions and marketing. With a presence at Sundance, Cannes, Toronto, Venice, Tribeca, SXSW, New York and Los Angeles film festivals, 42West plays a key role in supporting the sales of acquisition titles as well as launching a film through a festival publicity campaign. Past Sundance Films the company has represented include Joanna Hogg’s THE SOUVENIR (winner of World Cinema Grand Jury Prize: Dramatic), Lee Cronin’s THE HOLE IN THE GROUND, Paul Dano’s WILDLIFE, Sara Colangelo’s THE KINDERGARTEN TEACHER (winner of Director in U.S. competition), Maggie Bett’s NOVITIATE