Khoisan Influence Discernible in Sotho Toponyms

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Resources Policy and Mine Closure in South Africa: the Case of the Free State Goldfields

Resources Policy 38 (2013) 363–372 Contents lists available at SciVerse ScienceDirect Resources Policy journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/resourpol Resources policy and mine closure in South Africa: The case of the Free State Goldfields Lochner Marais n Centre for Development Support, University of the Free State, PO Box 339, Bloemfontein 9300, South Africa article info abstract Article history: There is increasing international pressure to ensure that mining development is aligned with local and Received 24 October 2012 national development objectives. In South Africa, legislation requires mining companies to produce Received in revised form Social and Labour Plans, which are aimed at addressing local developmental concerns. Against the 25 April 2013 background of the new mining legislation in South Africa, this paper evaluates attempts to address mine Accepted 25 April 2013 downscaling in the Free State Goldfields over the past two decades. The analysis shows that despite an Available online 16 July 2013 improved legislative environment, the outcomes in respect of integrated planning are disappointing, Keywords: owing mainly to a lack of trust and government incapacity to enact the new legislation. It is argued that Mining legislative changes and a national response in respect of mine downscaling are required. Communities & 2013 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved. Mine closure Mine downscaling Local economic development Free State Goldfields Introduction areas were also addressed. According to the new Act, mining companies are required to provide, inter alia, a Social and Labour For more than 100 years, South Africa's mining industry has Plan as a prerequisite for obtaining mining rights. These Social and been the most productive on the continent. -

The Anglo-Boer War, a Welsh Hospital in South Africa

24/05/2015 9:00 AM http://samilitaryhistory.org/vol123sw.html The South African Military History Society Die Suid-Afrikaanse Krygshistoriese Vereniging Military History Journal Vol 12 No 3 - June 2002 THE ANGLO-BOER WAR A WELSH HOSPITAL IN SOUTH AFRICA SA Watt, Pietermaritzburg The Welsh Hospital was one of a number of private initiatives in the medical services that were accepted and used by the British Government during the Anglo Boer War (1899-1902). It was organised by Professor Alfred W Hughes, assisted by a committee elected from the men and women of Wales. Funds amounting to £12 000 were acquired by subscription from the citizens of Wales and Welshmen residing outside the country. According to a Report by the Central British Red Cross Committee on the Voluntary Organisations in the Aid of the Sick and Wounded during the South African War, the personnel originally comprised three senior surgeons, two assistant surgeons, eight medical students and dressers, ten nursing sisters, two maids, 48 orderlies, cooks, and stretcher bearers. The medal roll lists 44 staff (W A Morgan, 1975, p 12). With them was the matron, Marion Lloyd. One of the senior surgeons was Professor Thomas Jones, who was a professor of surgery at Owen's College, Manchester, England (Report by the CBRCC, 1902; British Medical Journal, p 250). The personnel and equipment under the command of Major T W Cockerill embarked from Southampton on the Canada, 14 April 1900. The passage and freight was provided by the government. The stores, subsequently sent out, were shipped at the expense of the organisers. -

Ireland and the South African War, 1899-1902 by Luke Diver, M.A

Ireland and the South African War, 1899-1902 By Luke Diver, M.A. THESIS FOR THE DEGREE OF PH.D. DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY NATIONAL UNIVERSITY OF IRELAND MAYNOOTH Head of Department: Professor Marian Lyons Supervisors of Research: Dr David Murphy Dr Ian Speller 2014 i Table of Contents Page No. Title page i Table of contents ii Acknowledgements iv List of maps and illustrations v List of tables in main text vii Glossary viii Maps ix Personalities of the South African War xx 'A loyal Irish soldier' xxiv Cover page: Ireland and the South African War xxv Introduction 1 Chapter 1: Irish soldiers’ experiences in South Africa (October - December 1899) 19 Chapter 2: Irish soldiers’ experiences in South Africa (January - March 1900) 76 Chapter 3: The ‘Irish’ Imperial Yeomanry and the battle of Lindley 109 Chapter 4: The Home Front 152 Chapter 5: Commemoration 198 Conclusion 227 Appendix 1: List of Irish units 240 Appendix 2: Irish Victoria Cross winners 243 Appendix 3: Men from Irish battalions especially mentioned from General Buller for their conspicuous gallantry in the field throughout the Tugela Operations 247 ii Appendix 4: General White’s commendations of officers and men that were Irish or who were attached to Irish units who served during the period prior and during the siege of Ladysmith 248 Appendix 5: Return of casualties which occurred in Natal, 1899-1902 249 Appendix 6: Return of casualties which occurred in the Cape, Orange River, and Transvaal Colonies, 1899-1902 250 Appendix 7: List of Irish officers and officers who were attached -

Public Libraries in the Free State

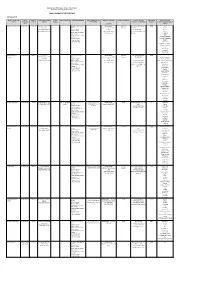

Department of Sport, Arts, Culture & Recreation Directorate Library and Archive Services PUBLIC LIBRARIES IN THE FREE STATE MOTHEO DISTRICT NAME OF FRONTLINE TYPE OF LEVEL OF TOWN/STREET/STREET STAND GPS COORDINATES SERVICES RENDERED SPECIAL SERVICES AND SERVICE STANDARDS POPULATION SERVED CONTACT DETAILS REGISTERED PERIODICALS AND OFFICE FRONTLINE SERVICE NUMBER NUMBER PROGRAMMES CENTER/OFFICE MANAGER MEMBERS NEWSPAPERS AVAILABLE IN OFFICE LIBRARY: (CHARTER) Bainsvlei Public Library Public Library Library Boerneef Street, P O Information and Reference Library hours: 446 142 Ms K Niewoudt Tel: (051) 5525 Car SA Box 37352, Services Ma-Tue, Thu-Fri: 10:00- (Metro) 446-3180 Fair Lady LANGENHOVENPARK, Outreach Services 17:00 Fax: (051) 446-1997 Finesse BLOEMFONTEIN, 9330 Electronic Books Wed: 10:00-18:00 karien.nieuwoudt@mangau Hoezit Government Info Services Sat: 8:30-12:00 ng.co.za Huisgenoot Study Facilities Prescribed books of tertiary Idees Institutions Landbouweekblad Computer Services: National Geographic Internet Access Rapport Word Processing Rooi Rose SA Garden and Home SA Sports Illustrated Sarie The New Age Volksblad Your Family Bloemfontein City Public Library Library c/o 64 Charles Information and Reference Library hours: 443 142 Ms Mpumie Mnyanda 6489 Library Street/West Burger St, P Services Ma-Tue, Thu-Fri: 10:00- (Metro) 051 405 8583 Africa Geographic O Box 1029, Outreach Services 17:00 Architect and Builder BLOEMFONTEIN, 9300 Electronic Books Wed: 10:00-18:00 Tel: (051) 405-8583 Better Homes and Garden n Government Info -

147 Reports December 2020

147 reports December 2020 Internal parasites Intestinal Roundworms (December 2020) jkccff Balfour, Grootvlei, Lydenburg, Middelburg, Nelspruit, Piet Retief, Standerton, Bapsfontein, Bronkhorstspruit, Hammanskraal, Magaliesburg, Nigel, Onderstepoort, Pretoria, Rayton, Makhado, Brits, Christiana, Potchefstroom, Ventersdorp, Zeerust, Bloemfontein, Bultfontein, Clocolan, Dewetsdorp, Ficksburg, Frankfort, Hertzogville, Hoopstad, Kroonstad, Oranjeville, Reitz, Senekal, Viljoenskroon, Warden, Winburg, Camperdown, Eshowe, Estcourt, Mtubatuba, Pietermaritzburg, Cradock, Graaff-Reinet, Humansdorp, Witelsbos, Caledon, George, Heidelberg, Riversdale, Stellenbosch, Vredenburg, Wellington, Colesberg, Kimberley Internal parasites – Resistant roundworms (December 2020) jkccff Pretoria, Bloemfontein, Hoopstad, Reitz, Eshowe, Underberg x Internal parasites – Tapeworms (December 2020)jkccff Balfour, Middelburg, Nelspruit, Standerton, Bapsfontein, Magaliesburg, Pretoria, Polokwane, Bloemfontein, Clocolan, Kroonstad, Memel, Reitz, Underberg, Graaff-Reinet, Humansdorp 00 Internal parasites – Tapeworms Cysticercosis (measles) (December 2020) jkccff Volksrust, Bronkhorstspruit, Mokopane, George, Paarl, Kimberley 00 Internal parasites – Liver fluke worms (December 2020)jkccff Bethlehem, Reitz, Winburg, Underberg, George, Malmesbury Internal parasites – Conical fluke (December 2020) jkccff Nigel, Kroonstad, Reitz, Winburg, Pietermaritzburg, Vryheid Internal parasites – Parafilaria (December 2020) jkccff Volksrust, Nigel, Stella, Mtubatuba, Vryheid Blue ticks (December -

Review of Existing Infrastructure in the Orange River Catchment

Study Name: Orange River Integrated Water Resources Management Plan Report Title: Review of Existing Infrastructure in the Orange River Catchment Submitted By: WRP Consulting Engineers, Jeffares and Green, Sechaba Consulting, WCE Pty Ltd, Water Surveys Botswana (Pty) Ltd Authors: A Jeleni, H Mare Date of Issue: November 2007 Distribution: Botswana: DWA: 2 copies (Katai, Setloboko) Lesotho: Commissioner of Water: 2 copies (Ramosoeu, Nthathakane) Namibia: MAWRD: 2 copies (Amakali) South Africa: DWAF: 2 copies (Pyke, van Niekerk) GTZ: 2 copies (Vogel, Mpho) Reports: Review of Existing Infrastructure in the Orange River Catchment Review of Surface Hydrology in the Orange River Catchment Flood Management Evaluation of the Orange River Review of Groundwater Resources in the Orange River Catchment Environmental Considerations Pertaining to the Orange River Summary of Water Requirements from the Orange River Water Quality in the Orange River Demographic and Economic Activity in the four Orange Basin States Current Analytical Methods and Technical Capacity of the four Orange Basin States Institutional Structures in the four Orange Basin States Legislation and Legal Issues Surrounding the Orange River Catchment Summary Report TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTION ..................................................................................................................... 6 1.1 General ......................................................................................................................... 6 1.2 Objective of the study ................................................................................................ -

Directory of Organisations and Resources for People with Disabilities in South Africa

DISABILITY ALL SORTS A DIRECTORY OF ORGANISATIONS AND RESOURCES FOR PEOPLE WITH DISABILITIES IN SOUTH AFRICA University of South Africa CONTENTS FOREWORD ADVOCACY — ALL DISABILITIES ADVOCACY — DISABILITY-SPECIFIC ACCOMMODATION (SUGGESTIONS FOR WORK AND EDUCATION) AIRLINES THAT ACCOMMODATE WHEELCHAIRS ARTS ASSISTANCE AND THERAPY DOGS ASSISTIVE DEVICES FOR HIRE ASSISTIVE DEVICES FOR PURCHASE ASSISTIVE DEVICES — MAIL ORDER ASSISTIVE DEVICES — REPAIRS ASSISTIVE DEVICES — RESOURCE AND INFORMATION CENTRE BACK SUPPORT BOOKS, DISABILITY GUIDES AND INFORMATION RESOURCES BRAILLE AND AUDIO PRODUCTION BREATHING SUPPORT BUILDING OF RAMPS BURSARIES CAREGIVERS AND NURSES CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — EASTERN CAPE CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — FREE STATE CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — GAUTENG CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — KWAZULU-NATAL CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — LIMPOPO CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — MPUMALANGA CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — NORTHERN CAPE CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — NORTH WEST CAREGIVERS AND NURSES — WESTERN CAPE CHARITY/GIFT SHOPS COMMUNITY SERVICE ORGANISATIONS COMPENSATION FOR WORKPLACE INJURIES COMPLEMENTARY THERAPIES CONVERSION OF VEHICLES COUNSELLING CRÈCHES DAY CARE CENTRES — EASTERN CAPE DAY CARE CENTRES — FREE STATE 1 DAY CARE CENTRES — GAUTENG DAY CARE CENTRES — KWAZULU-NATAL DAY CARE CENTRES — LIMPOPO DAY CARE CENTRES — MPUMALANGA DAY CARE CENTRES — WESTERN CAPE DISABILITY EQUITY CONSULTANTS DISABILITY MAGAZINES AND NEWSLETTERS DISABILITY MANAGEMENT DISABILITY SENSITISATION PROJECTS DISABILITY STUDIES DRIVING SCHOOLS E-LEARNING END-OF-LIFE DETERMINATION ENTREPRENEURIAL -

South Africa)

FREE STATE PROFILE (South Africa) Lochner Marais University of the Free State Bloemfontein, SA OECD Roundtable on Higher Education in Regional and City Development, 16 September 2010 [email protected] 1 Map 4.7: Areas with development potential in the Free State, 2006 Mining SASOLBURG Location PARYS DENEYSVILLE ORANJEVILLE VREDEFORT VILLIERS FREE STATE PROVINCIAL GOVERNMENT VILJOENSKROON KOPPIES CORNELIA HEILBRON FRANKFORT BOTHAVILLE Legend VREDE Towns EDENVILLE TWEELING Limited Combined Potential KROONSTAD Int PETRUS STEYN MEMEL ALLANRIDGE REITZ Below Average Combined Potential HOOPSTAD WESSELSBRON WARDEN ODENDAALSRUS Agric LINDLEY STEYNSRUST Above Average Combined Potential WELKOM HENNENMAN ARLINGTON VENTERSBURG HERTZOGVILLE VIRGINIA High Combined Potential BETHLEHEM Local municipality BULTFONTEIN HARRISMITH THEUNISSEN PAUL ROUX KESTELL SENEKAL PovertyLimited Combined Potential WINBURG ROSENDAL CLARENS PHUTHADITJHABA BOSHOF Below Average Combined Potential FOURIESBURG DEALESVILLE BRANDFORT MARQUARD nodeAbove Average Combined Potential SOUTPAN VERKEERDEVLEI FICKSBURG High Combined Potential CLOCOLAN EXCELSIOR JACOBSDAL PETRUSBURG BLOEMFONTEIN THABA NCHU LADYBRAND LOCALITY PLAN TWEESPRUIT Economic BOTSHABELO THABA PATSHOA KOFFIEFONTEIN OPPERMANSDORP Power HOBHOUSE DEWETSDORP REDDERSBURG EDENBURG WEPENER LUCKHOFF FAURESMITH houses JAGERSFONTEIN VAN STADENSRUST TROMPSBURG SMITHFIELD DEPARTMENT LOCAL GOVERNMENT & HOUSING PHILIPPOLIS SPRINGFONTEIN Arid SPATIAL PLANNING DIRECTORATE ZASTRON SPATIAL INFORMATION SERVICES ROUXVILLE BETHULIE -

Caledon–Bloemfontein Government Water Scheme

CALEDon–BLOEMFONTEIN GOVERNMENT WATER SCHEME South Africa Modder Krugersdrift Dam Bloemhof Dam Catchment Mazelspoort Weir LOCATION Bainsvlei W Mockes Dam Kora The Caledon–Modder Transfer Scheme consists of two transfer schemes, namely the original nna Hamilton Park BLOEMFONTEIN Bloemdustria Caledon–Bloemfontein Government Water Scheme and the Novo Transfer scheme, which Brandkop Boesmanskop Bloemspruit Sepane Thaba Nchu are situated in the Upper Orange Catchment. Mo dd De Brug e Seroalo Dam Grootvlei r Newbury Botshabelo Dam Bloemdustria Lovedale DESCRIPTION Kgabanyana Dam W Kle Rustfontein in Lesaka Dam Modder Groothoek The Caledon–Bloemfontein Government Water Scheme and Novo Transfer schemes are Dam Armenia W Dam two of the three main schemes used to supplement the Riet–Modder Catchment due to Caledon-Bloemfontein the full utilisation of the water resources within the catchment, the third main scheme Ganna being the Orange–Riet Transfer. The Mazelpoort Scheme was developed by Mangaung Leeu Municipality. The Caledon–Bloemfontein Government Water Scheme and Novo Transfer, Riet-Modder together with the Mazelpoort Scheme situated on the Modder River, form one integrated Catchment Uitkyk DEWETSDORP supply system serving the Mangaung area. SOUTH AFRICA The Caledon–Bloemfontein Government Water Scheme is operated by Bloem Water, REDDERSBURG Caledon LESOTHO and consists of Welbedacht, Rustfontein and Knellpoort dams, along with other service Riet reservoirs, pump stations and water treatment works. Peri-urban area/urban area P P Town Knellpoort 3 The storage capacity of the Welbedacht Dam reduced from 115 million m to approximately Dam Tienfontein International boundary 16 million m3 in only 20 years due to siltation. This impacted the assurance of supply to River and dam Welbedacht Dam Bloemfontein and so Knellpoort Dam was constructed (off channel storage) to augment De Hoek Pipeline and reservoir the supply. -

Of Local Mourning: the South African War and State Commemoration

Society in Transition ISSN: 1028-9852 (Print) (Online) Journal homepage: https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rssr19 A ‘secret history’ of local mourning: The South African War and state commemoration Liz Stanley To cite this article: Liz Stanley (2002) A ‘secret history’ of local mourning: The South African War and state commemoration, Society in Transition, 33:1, 1-25, DOI: 10.1080/21528586.2002.10419049 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/21528586.2002.10419049 Published online: 12 Jan 2012. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 64 View related articles Citing articles: 8 View citing articles Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=rssr20 Society in Transition 2002, 33(1) .· A 'secret history' of local mourning: the South African War and state commemoration Liz Stanley Sociology/Women's Studies, University of Manchester Manchester M13 9PL, UK liz. [email protected]@man. a c. uk A central claim in the war commemoration literature is that World War I brought about a fundamental change in state commemorative practices. This argument is problematised using a case study concerned with the relationship between local mourning, state commemoration and remem brancefollowingbrance following the South African War of 1899-1902, in which meanings about nationalism, belonging and citizenship have been inscribed within a 'legendary topography' which has concretised remembrance in commemo rative memorials and monuments. Two silences in commemoration from this War - a partial one concerning children and a more total one con cerning all black people - are teased out in relation to the Vrouemonument built in 1913, the Gedenktuine or Gardens of Remembrance constructed during the 1960s and 70s, and some post-1994 initiatives, and also related to ideas about citizenship and belonging. -

Free State Provincial Government

FREE STATE PROVINCIAL GOVERNMENT “A prosperous and equitable Free State Province through safe and efficient transport and infrastructure systems” Department of Public Works, Roads and Transport: Generic Strategic Plan 2003/2004 – 2005/2006 TABLE OF CF CONTENTS 1 POLICY STATEMENT..............................................................................................................4 2 OVERVIEW BY THE ACCOUNTING OFFICER..................................................................6 3 VISION.........................................................................................................................................7 4 MISSION......................................................................................................................................7 5 VALUE SYSTEM........................................................................................................................7 6 LEGISLATIVE AND OTHER MANDATES ...........................................................................8 7 DESCRIPTION OF THE STATUS QUO................................................................................9 8 DESCRIPTION OF STRATEGIC PLANNING PROCESS ...............................................13 9 DEPARTMENTAL STRATEGIC GOALS AND STRATEGIC OBJECTIVES...............15 10 MEASURABLE OBJECTIVES, OUTPUTS AND PERFORMANCE MEASURES ..17 10.1 PROGRAMME 1: CORPORATE SERVICES DIRECTORATE ......................... 17 10.2 PROGRAMME 2: ORGANISATIONAL DEVELOPMENT DIRECTORATE... 23 10.3 PROGRAMME 3: WORKS INFRASTRUCTURE.............................................. -

Biodiversity Plan V1.0 Free State Province Technical Report (FSDETEA/BPFS/2016 1.0)

Biodiversity Plan v1.0 Free State Province Technical Report (FSDETEA/BPFS/2016_1.0) DRAFT 1 JUNE 2016 Map: Collins, N.B. 2015. Free State Province Biodiversity Plan: CBA map. Report Title: Free State Province Biodiversity Plan: Technical Report v1.0 Free State Department of Economic, Small Business Development, Tourism and Environmental Affairs. Internal Report. Date: $20 June 2016 ______________________________ Version: 1.0 Authors & contact details: Nacelle Collins Free State Department of Economic Development, Tourism and Environmental Affairs [email protected] 051 4004775 082 4499012 Physical address: 34 Bojonala Buidling Markgraaf street Bloemfontein 9300 Postal address: Private Bag X20801 Bloemfontein 9300 Citation: Report: Collins, N.B. 2016. Free State Province Biodiversity Plan: Technical Report v1.0. Free State Department of Economic, Small Business Development, Tourism and Environmental Affairs. Internal Report. 1. Summary $what is a biodiversity plan This report contains the technical information that details the rationale and methods followed to produce the first terrestrial biodiversity plan for the Free State Province. Because of low confidence in the aquatic data that were available at the time of developing the plan, the aquatic component is not included herein and will be released as a separate report. The biodiversity plan was developed with cognisance of the requirements for the determination of bioregions and the preparation and publication of bioregional plans (DEAT, 2009). To this extent the two main products of this process are: • A map indicating the different terrestrial categories (Protected, Critical Biodiversity Areas, Ecological Support Areas, Other and Degraded) • Land-use guidelines for the above mentioned categories This plan represents the first attempt at collating all terrestrial biodiversity and ecological data into a single system from which it can be interrogated and assessed.