Sanford Biggers/MATRIX

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

APT Insights

Vol.1 Fall 2007 A quarterly publication of the Artist Pension Trust ® 2,3 . Brief, Letter 4 . Modern Marks. India 11 . Beyond Borders 17 . Escultura Social 22 . Istanbul Biennial 28 . Performa 07 34 . The Turner Prize 07 40 . APT Curatorial 44 . APT Intelligence 46 . Insight/Art Explosion 48 . Insight/Art as an Asset Class Publisher APT Holding Worldwide Inc. (BVI) Editor Pamela Auchincloss Creative Director Jin Jung Associate Editor Jennie D’Amato Contributing Writers Pamela Auchincloss, Regine Basha, Tairone Bastien, Bijan Khezri, Kay Pallister, November Paynter, David A. Ross, Pilar Tompkins Administrative Assistants Frederick Janka, Yonni Walker Copyright (c) 2007 APT Holding Worldwide Inc. (BVI) All rights reserved. - Annual subscription US$40/€28 Individual copies US$10/€7 Plus shipping and handling. Contact: [email protected] 2,3 . Brief, Letter 4 . Modern Marks. India 11 . Beyond Borders 17 . Escultura Social 22 . Istanbul Biennial 28 . Performa 07 34 . The Turner Prize 07 40 . APT Curatorial 44 . APT Intelligence 46 . Insight/Art Explosion 48 . Insight/Art as an Asset Class Cr ed it / In tr odu c ti o n 1 Brief . Our ability to communicate the many activities, events and developments of the Artist Pension Trust® (APT) determines our long-term success. APT Insight is an important platform to engage with all our constituencies. For example, APT Curatorial Services, our active lending program, has taken a life of its own. Following successful exhibitions in Beijing, Tuscany and New Orleans in 2007, many more projects are under consideration for 2008. With a medium such as APT Insight, everyone will remain informed about the fast progress of our company. -

Biography Sanford Biggers

Biography Sanford Biggers Los Angeles, USA, 1970. Lives and works in New York SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2021 2021 - Contra/Diction, Scad Museum of Art, Savannah, USA 2021 - Oracle, Rockefeller Center, New York, USA 2020 2020 - Codeswitch, Bronx Museum, New York, USA 2020 - Sof Truths, Marianne Boesky Gallery, New York, USA 2019 2019 - Quadri Ed Angeli, David Castillo Gallery, Miami Beach, USA 2019 - Chimeras, Baldwin Gallery, Aspen, USA 2018 2018 - Just Us, For Freedoms, Charleston, USA 2018 - New Work, Monique Meloche Gallery, Chicago, USA 2018 - Sanford Biggers, Contemporary Art Museum St. Louis, Traveled to Madison, WI, Chazen Museum of Art, University of Wisconsin-Madison; Medford, MA, Tufs University Art Gallery, Tufs University, St. Louis, USA 2017 2017 - Selah, Marianne Boesky Gallery, New York, USA 2017 - Sanford Biggers: Falk Visiting Artist, curated by Emily Stamey, Weatherspoon Art Museum, Te University of North Carolina Greensboro, Greensboro, USA 2016 2016 - Hither and Yon, Massimo De Carlo, London, UK 2016 - Subjective Cosmology, MOCAD, Detroit, USA 2016 - NEW / NOW, New Britain Museum of American Art, Batchelor Gallery, New Britain, USA 2016 - Te pasts they brought with them, Monique Meloche Gallery, Chicago, USA 2016 - New Monuments – Sanford Biggers: Laocoön, Cressman Center for Visual Art, Louisville, USA 2016 - New Work, Monique Meloche Projects, New York, USA 2016 - Mantra, New Britain Museum of American Art, New Britain, USA 2015 2015 - Matter, David Castillo Gallery, Miami Beach, USA 2014 2014 - Vex, Baldwin Gallery, Aspen, -

The Playful, Political Art of Sanford Biggers an Under-Sung Artist Upends Received Ideas About Race and History

The Playful, Political Art of Sanford Biggers An under-sung artist upends received ideas about race and history. By Vinson Cunningham Biggers’s art, layered with references to race and history, is sincere and ironic at once. Photograph by Eric Helgas for The New Yorker Three years ago, on a Saturday in spring, I wandered into a humid gallery just south of Canal Street. On display was a group exhibition called “Black Eye,” which included works by an impressive roster of established and emerging artists—Kehinde Wiley, Wangechi Mutu, Steve McQueen, Kerry James Marshall, Deana Lawson, David Hammons, Lynette Yiadom-Boakye. The show, curated by Nicola Vassell, felt like a confirmation of my growing, and perhaps belated, realization that work by black artists had come to occupy an elevated position of regard in the art world. A few months before the show, McQueen had won the Academy Award for Best Picture, for “Twelve Years a Slave.” A year later, Wiley’s first career retrospective, “A New Republic,” opened at the Brooklyn Museum to widespread acclaim. In October, 2016, a towering retrospective of Marshall’s work, “Mastry,” was the first genuine hit at the newly opened Met Breuer. In May of last year, an exhibition of seventeen hauntingly quiet portraits by Yiadom- Boakye, at the New Museum, was a surprise sensation; as with the Marshall show, pictures of the works clogged the Instagram feeds of gallerygoers for weeks. People arrived at “Black Eye” in steady waves, and viewed the art with scholarly quietude. The pieces were uniformly strong, but my favorite, by far, was one of the least assuming: an untitled photograph of modest size, tucked away in a corner, framed in gold. -

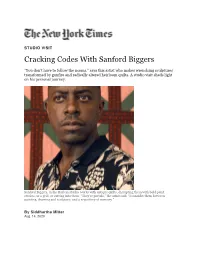

Cracking Codes with Sanford Biggers

STUDIO VISIT Cracking Codes With Sanford Biggers “You don’t have to follow the norms,” says this artist who makes wrenching sculptures transformed by gunfire and radically altered heirloom quilts. A studio visit sheds light on his personal journey. Sanford Biggers, in his Harlem studio, works with antique quilts, disrupting them with bold paint strokes, or a grid, or cutting into them. “They’re portals,” the artist said. “I consider them between painting, drawing and sculpture, and a repository of memory.” By Siddhartha Mitter Aug. 14, 2020 One afternoon in June, the artist Sanford Biggers, having returned to the city after a stretch bunkered out of town with his wife and young daughter to avoid the pandemic, opened up his expansive basement studio in Harlem for a socially-distanced visit. Mr. Biggers is a specialist in many styles, and several were in evidence. A shimmering silhouette made entirely of black sequins, for instance, towered along one wall; it depicted a Black Power protester drawn from a late-1960s photograph. There were African statuettes that Mr. Biggers purchases in markets, then dips in wax and modifies at the shooting range — a wrenching sculpture-by-gunfire that he has exhibited as multichannel videos. There were also busts from a series he is making in bronze and another in marble, with artisans in Italy. They merge Masai, Luba, and other African sculptural traits with ones from the Greco-Roman tradition. Most of all, there were quilts — stretched against the wall, piled onto pallets, in scraps on the cutting table. For over a decade, Mr. -

Grain of Emptiness: Exhibition Press Release

FROM: Rubin Museum of Art 150 West 17th Street, NYC, 10011 Contact: Anne-Marie Nolin Phone: (212) 620 5000 x276 E-mail: [email protected] FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE July 2010 BUDDHISM’S INFLUENCE ON CONTEMPORARY ARTISTS EXPLORED BY THE RUBIN MUSEUM OF ART New York, NY—From November 5, 2010 to April 11, 2011, the Rubin Museum of Art will present works by five artists of different generations and ethnicities, working between 1960 and the present, whose oeuvres have been influenced by the tenets of Buddhism, including its central principles of emptiness and the fleeting nature of all things. Grain of Emptiness: Buddhism-Inspired Contemporary Art assembles videos, paintings, photographs, and installations dating from 1961 to 2008 by Sanford Biggers (b. U.S., 1970); Theaster Gates (b. U.S.,1973); Atta Kim (b. Korea, 1956); Wolfgang Laib (b. West Germany, 1950); and Charmion von Wiegand (U.S., 1896-1983). Biggers and Gates will each present new site-specific performance works. The exhibition highlights the continuously evolving nature of art inspired by Buddhist ideas and themes. “These artists are inheritors of a rich tradition that threads throughout modern and contemporary art,” says Martin Brauen, organizer of Grain of Emptiness and Chief Curator at the Rubin Museum of Art. “The ideas of emptiness and impermanence, embraced by the Abstract Expressionists in the 1950s, have since been taken up by such cultural icons as John Cage and Merce Cunningham, as well as by conceptual and performance artists and others who have sought to explore in art how the insights of Buddhism intersect with everyday life.” In the exhibition, the viewer will encounter several paintings by Charmion von Wiegand, an undeservedly little known painter, critic, and journalist. -

Contact: Ina Wudtke Schwedter Str. 250 D-10119 Berlin Mobile: +49 (0)173 4383194 E-Mail: [email protected]

Contact: Ina Wudtke Schwedter Str. 250 D-10119 Berlin mobile: +49 (0)173 4383194 e-mail: [email protected] www.blacksoundwhitecube.com Press release Black Sound White Cube Exhibition at the Kunstquartier Bethanien / Studio 1 July 10 - August 28, 2011, in Berlin Exhibition venue: Kunstquartier Bethanien / Studio 1 Mariannenplatz 2, D-10997 Berlin Metro station: Kottbusser Tor Opening hours: July 10 - August 28, 2011, daily from 12 – 7 pm Participating artists: Sanford Biggers, Sonia Boyce, Nate Harrison, Jennie C. Jones, Minouk Lim, Yvette Mattern, Robin Rhode, Nadine Robinson, Maruša Sagadin, Ina Wudtke Curated by: Dieter Lesage and Ina Wudtke Opening: Saturday, July 9, 2011, 5 – 9 p.m. Admission: Exhibition and lectures: 3 euros (free admission for children and youths, trainees, students, recipients of social welfare, severely disabled persons, and pensioners) Lectures & Artist’s Talks: July 10, 2011 4 p.m.: Sanford Biggers’ Performance with Satch Hoyt (Berlin) 5 p.m.: Artist’s talk with Sanford Biggers (NY) 6 p.m.: Artist’s talk with Nadine Robinson (NY) July 29, 2011 6 p.m.: Lecture by Valerie Cassel Oliver (Curator CAMH - Contemporary Arts Museum Houston) August 27, 2011 6 p.m.: Lecture by Franklin Sirmans (Curator LACMA - Los Angeles County Museum of Art) 7 p.m.: Artist’s talk with Sonia Boyce (London) 1 The exhibition Black Sound White Cube The exhibition Black Sound White Cube will present works by ten international artists that refer to the musical traditions of the Afro-Atlantic diaspora. Black Sound White Cube thus seeks to trigger discussions off the beaten track of the hegemonic fields of avant-garde and pop. -

Artist Sanford Biggers to Present Selah, His First Solo Exhibition at Marianne Boesky Gallery Featuring New Sculpture, Paintings, and Installations

Artist Sanford Biggers to Present Selah, His First Solo Exhibition at Marianne Boesky Gallery Featuring New Sculpture, Paintings, and Installations On View September 7 - October 21, 2017 Opening Reception September 7, 6:00-8:00 PM Marianne Boesky Gallery is pleased to present Sanford Biggers’ Selah, the artist’s inaugural solo exhibition with the gallery. Taking inspiration from American History and the human form, Biggers will create an experience that highlights often overlooked cultural and political narratives through symbolic gestures and imagery. Selah will be on view from September 7 to October 21, 2017 in the gallery’s 507 W. 24th Street space, with a special installation presented in one of the gallery’s viewing rooms. Biggers’ expansive body of work encompasses painting, sculptures, textiles, video, film, multi-component installations, and performance. His syncretic practice positions him as a collaborator with the past, adding his own voice and perspective to those who made and used the antique quilts, African sculptures, and cultural imagery his work references. Biggers cuts, paints, reshapes, and alters objects and images—both found and created by himself—leveraging their formal and conceptual qualities to reimagine and amplify certain narratives and perspectives. His works speak to current social, political, and economic happenings as well as to the historic context that bore them. The interrelated components and aesthetic diversity of Biggers’ works provide a multifaceted platform for dialogue and debate. Selah – Anchoring the exhibition is Seated Warrior, a new figure from his BAM series, which includes videos and bronze works made from wooden African sculptures that the artist collected, dipped in wax, and transmogrified with piercing bullets and subsequently cast in bronze as a response to recent and ongoing occurrences of police brutality against Black Americans. -

Wallach Art Gallery to Open Uptown Triennial 2020 At

WALLACH ART GALLERY TO OPEN UPTOWN TRIENNIAL 2020 AT THE COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY LENFEST CENTER FOR THE ARTS NEW YORK, NY, September 23, 2020 – The Wallach Art Gallery at Columbia University is pleased to open Uptown Triennial 2020, the second iteration in the series, presenting the work of contemporary artists in dialogue with the Harlem Renaissance—a defining moment in American modernism and African-American cultural history—during its centennial year. The exhibition opens to Columbia students, faculty, and staff on September 24, 2020 (reservations are required) and with a 3D virtual tour for the broader community. Full public access to the gallery is expected later this fall. Reservations to the exhibition, links to the 3D virtual tour and updates on gallery access are available at wallach.columbia.edu. The exhibition closes on December 13, 2020. Uptown Triennial 2020 is organized by Wallach director and chief curator, Betti-Sue Hertz. “The exhibition features 25 artists whose works project a confidence in Black identity that reflects a quest for making visible emerging subjectivities that mine popular and historical iconographies,” said Hertz. Uptown Triennial 2020 includes works by artists Derrick Adams,Tariq Al-Sabir, Dawoud Bey, Sanford Biggers, Kabuya Pamela Bowens-Saffo, Jordan Casteel, Renee Cox, Gerald Cyrus, Priyanka Dasgupta & Chad Marshall, Damien Davis, Delano Dunn, Awol Erizku, Derek Fordjour, Hugh Hayden, Leslie Hewitt, Jennie C. Jones, Kahlil Joseph, Autumn Knight, Whitfield Lovell, Glendalys Medina, Rashaun Rucker, Xaviera Simmons, Dianne Smith, and LeRone Wilson. These 25 accomplished artists work in a wide range of media including painting, photography, video, sculpture, installation and performance. -

Sanford Biggers (B

Gallery Guide Sanford Biggers (b. 1970 in Los Angeles; lives and Related Programs Contemporary Art works in New York City) has made installations, videos, Museum St. Louis and performances that have appeared in venues Artist Talk: Sanford Biggers worldwide including the Tate Britain and Tate Modern Thursday, September 6, 6:30 pm September 7– in London; the Whitney Museum, the New Museum, the December 30, 2018 Apollo Theater, and The Studio Museum in Harlem, New RE: Black Visual Mourning York; and the Los Angeles Museum of Contemporary Wednesday, October 10, 6:30 pm Art; as well as institutions in China, Germany, Hungary, Japan, Poland, and Russia. A solo exhibition at Monique Meloche Gallery, in Chicago, opens on September 15, 2018. The artist’s works have been included in notable A full-color, 52-page, illustrated catalog will exhibitions such as: Prospect.1 New Orleans biennial, accompany the exhibition, with contributions by Illuminations at the Tate Modern, Performa 07 in New Lisa Melandri and Kahlil Gibran Muhammad, among York, the Whitney Biennial, and Freestyle at The Studio other authors. The catalog is produced by Lucia | Sanford Biggers Museum in Harlem. His works are included in the Marquand, Seattle. collections of the Museum of Modern Art, Walker Art Center, Whitney Museum of American Art, Brooklyn Museum, Bronx Museum of the Arts, Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago, Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture, and the new Legacy Museum in Montgomery, Alabama. An outdoor exhibition of his public sculpture continues at Sculpture Milwaukee through October 21, 2018. -

Syncretic Improvisations: a Conversation with Sanford Biggers by Jan Garden Castro

Syncretic Improvisations: A Conversation with Sanford Biggers By Jan Garden Castro While working in Japan, Italy, Germany, Poland, Brazil, and the United States, Sanford Biggers honed his view that art may simultaneously embrace diverse cultures. For example, he sees the tree as a symbol of growth and connectedness to earth, as the natural form under which Buddha found enlightenment, and as slavery’s lynching post. Others may see Christian, Greek, and other myths, so the readings are virtually limitless. In Blossom, in which a tree breaks out of a The Cartographer’s Conundrum, 2012. Piano, pipe organ pipes, repurposed musical instruments, piano, Biggers connects mirrored glass, Plexiglas, found church pews, linoleum tiles, and sound, view of installation at arboreal mythologies with the MASS MoCa. cultural sphere of music and art—from Beuys’s felt-covered piano to composers ranging from Beethoven to Fats Waller. For Biggers, forms are multivalent, embodying a range of associations, some negative, some positive. This emphasis on the transformative power of art charms us into realizing that human nature may also change. Biggers’s exhibition schedule is packed, and he wows audiences whether he’s showing visual art, performing with his group Moon Medicine, or hosting discussions with celebrities like Marcus Samuelsson and Yassin Bey (formerly Mos Def). On the heels of his 2011 exhibitions—“Sweet Funk: an Introspective” at the Brooklyn Museum and “Cosmic Voodoo Circus” at the Sculpture-Center in Long Island City—Biggers opened 2012 with “Moon Medicine” at the University of the South in Sewanee, Tennessee; “Codex,” a solo exhibition at the Ringling Museum in Sarasota, Florida (through October 14); and The Cartographer’s Conundrum, a massive installation at MASS MoCA (through October). -

Sanford Biggers

Marianne Boesky Gallery Now Represents Multidisciplinary Artist Sanford Biggers Works by the Artist to be Featured in the Gallery’s Presentation at Art Basel Miami Beach New York—October 19, 2016—Marianne Boesky Gallery is pleased to announce representation of artist Sanford Biggers, whose practice encompasses installation, film, video, drawing, sculpture, original music, and performance. Biggers’ work deals with well-recognized social, political, and cultural narratives, which he reinterprets to highlight new and underlying perspectives. The gallery will feature Biggers’ work as part of its presentation at Art Basel Miami Beach in December, to be followed by a solo exhibition in New York in 2017. Leveraging the formal qualities of the vast range of media with which he works, Biggers creates installations and “vignettes” that inspire dialogue on issues such as formalism, the shifting meaning of symbols, nostalgia, history, the figure, and the complexities of identity in today's social and political landscape. Biggers’ work is as visually compelling as it is conceptually complex, taking viewers on a journey from initial aesthetic encounter through the many embedded layers of meaning to create what he terms, “a future ethnography.” Among his diverse works is BAM (2015), which is comprised of a series of wooden African sculptures that the artist collected, dipped in wax, and reshaped through gunshots as a response to recent and ongoing occurrences of police brutality against African-Americans. The work also comments on ideas of obliteration, physical and metaphoric, while complicating the Classical figure in sculpture. In another work, Lotus (2007), the artist etched lotus petals into a seven-foot tall disc that upon closer examination reveal images of the lower decks of slave ships—the bodies crammed and arranged to highest efficiency. -

Sanford Biggers February 9 – March 15, 2008 Opening Reception: Saturday February 9, 6-8Pm

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: Sanford Biggers February 9 – March 15, 2008 Opening Reception: Saturday February 9, 6-8pm D’Amelio Terras is pleased to present an exhibition of Sanford Biggers: an installation composed of a single channel video projection titled Cheshire and a sculpture of a broad smiling mouth will be on view in the front room gallery. The video “Cheshire” was first exhibited in “Blossom,” a three part solo exhibition at Grand Arts in Kansas city in September 2007 where it was projected outdoor on an exterior wall of a theater in downtown Kansas city. Located within a gallery space, the combination of video and sculpture functions as a theatrical installation developing themes of African American representation in pictures, which has been central to Sanford Biggers’ multi media practice. The theatricality of the installation continues his performance commissioned by Performa 07 “The Somethin’ Suite”, in which a short section of the video appeared while a live performance of the song Strange Fruit by the performer Imani Uzuri in geisha make-up took place. This unusual performance of the famous Billie Holiday piece is now part of the soundtrack of “Cheshire” at mid point in the video. The 13’40” long single-channel projection shows different professional black men dressed in work uniform climbing or trying to climb a tree. One after another, they approach a tree of their choice in different locations (California and Germany) - the camera zooms in and out their action until, if they succeed, the climber reaches a comfortable position in the tree. The paradox between the outdoor setting and the uncanny action of an adult in professional clothes climbing a tree gives a surreal atmosphere: the men do not act based on a director’s script, they simply execute the task of climbing the tree without other apparent motive than a self imposed challenge.