A Study of Gian Carlo Menotti's the Consul, the Saint of Bleecker

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Midsummer Night's Dream

Monday 25, Wednesday 27 February, Friday 1, Monday 4 March, 7pm Silk Street Theatre A Midsummer Night’s Dream by Benjamin Britten Dominic Wheeler conductor Martin Lloyd-Evans director Ruari Murchison designer Mark Jonathan lighting designer Guildhall School of Music & Drama Guildhall School Movement Founded in 1880 by the Opera Course and Dance City of London Corporation Victoria Newlyn Head of Opera Caitlin Fretwell Chairman of the Board of Governors Studies Walsh Vivienne Littlechild Dominic Wheeler Combat Principal Resident Producer Jonathan Leverett Lynne Williams Martin Lloyd-Evans Language Coaches Vice-Principal and Director of Music Coaches Emma Abbate Jonathan Vaughan Lionel Friend Florence Daguerre Alex Ingram de Hureaux Anthony Legge Matteo Dalle Fratte Please visit our website at gsmd.ac.uk (guest) Aurelia Jonvaux Michael Lloyd Johanna Mayr Elizabeth Marcus Norbert Meyn Linnhe Robertson Emanuele Moris Peter Robinson Lada Valešova Stephen Rose Elizabeth Rowe Opera Department Susanna Stranders Manager Jonathan Papp (guest) Steven Gietzen Drama Guildhall School Martin Lloyd-Evans Vocal Studies Victoria Newlyn Department Simon Cole Head of Vocal Studies Armin Zanner Deputy Head of The Guildhall School Vocal Studies is part of Culture Mile: culturemile.london Samantha Malk The Guildhall School is provided by the City of London Corporation as part of its contribution to the cultural life of London and the nation A Midsummer Night’s Dream Music by Benjamin Britten Libretto adapted from Shakespeare by Benjamin Britten and Peter Pears -

8.112023-24 Bk Menotti Amelia EU 26-03-2010 9:41 Pagina 16

8.112023-24 bk Menotti Amelia_EU 26-03-2010 9:41 Pagina 16 Gian Carlo MENOTTI Also available The Consul • Amelia al ballo LO M CAR EN N OT IA T G I 8.669019 19 gs 50 din - 1954 Recor Patricia Neway • Marie Powers • Cornell MacNeil 8.669140-41 Orchestra • Lehman Engel Margherita Carosio • Rolando Panerai • Giacinto Prandelli Chorus and Orchestra of La Scala, Milan • Nino Sanzogno 8.112023-24 16 8.112023-24 bk Menotti Amelia_EU 26-03-2010 9:41 Pagina 2 MENOTTI CENTENARY EDITION Producer’s Note This CD set is the first in a series devoted to the compositions, operatic and otherwise, of Gian Carlo Menotti on Gian Carlo the occasion of his centenary in 2011. The recordings in this series date from the mid-1940s through the late 1950s, and will feature several which have never before appeared on CD, as well as some that have not been available in MENOTTI any form in nearly half a century. The present recording of The Consul, which makes its CD début here, was made a month after the work’s (1911– 2007) Philadelphia première. American Decca was at the time primarily a “pop” label, the home of Bing Crosby and Judy Garland, and did not yet have much experience in the area of Classical music. Indeed, this recording seems to have been done more because of the work’s critical acclaim on the Broadway stage than as an opera, since Decca had The Consul also recorded Arthur Miller’s Death of a Salesman with members of the original cast around the same time. -

Children in Opera

Children in Opera Children in Opera By Andrew Sutherland Children in Opera By Andrew Sutherland This book first published 2021 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2021 by Andrew Sutherland Front cover: ©Scott Armstrong, Perth, Western Australia All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-5275-6166-6 ISBN (13): 978-1-5275-6166-3 In memory of Adrian Maydwell (1993-2019), the first Itys. CONTENTS List of Figures........................................................................................... xii Acknowledgements ................................................................................. xxi Chapter 1 .................................................................................................... 1 Introduction What is a child? ..................................................................................... 4 Vocal development in children ............................................................. 5 Opera sacra ........................................................................................... 6 Boys will be girls ................................................................................. -

Last Name First Name Middle Name Reference No. Collection Site

PASSPORTS APPLIED IN PCG DUBAI/FSPsRCOsManila/VFS(PaRC) PASSPORTS READY FOR RELEASE AS OF 29 August 2021 RELEASING SECTION 8-12NN, 1-5PM, SUN-THU, EXCEPT HOLIDAYS TO SEARCH FOR YOUR NAME press "CONTROL F" OR "F3". If your name is already listed, please proceed to your designated Collection Site with your OLD PASSPORT AND OFFICIAL RECEIPT to claim your new e- passport. If the applicant cannot come personally to collect the passport, authorize someone to pick-up the passport. The following are the requirements: AUTHORIZATION LETTER, OLD PASSPORT, ORIGINAL RECEIPT, AND ORIGINAL AND COPY OF VALID IDENTIFICATION CARD OF AUTHORIZED REPRESENTATIVE. WRITE THE REFERENCE NUMBER AT THE TOP OF YOUR RECEIPT UPON CLAIMING YOUR PASSPORT Middle Collection Last name First name Reference No. name Site AARTS ESRA MAE R. 2000106100360 DubaiPCG ABABA ROLANDO JR. I. 2000134000360 DubaiPCG ABACAN RENELYN D. 2000122300360 DubaiPCG ABAD MARIA EMMA D. 2000120550360 DubaiPCG ABAD CRISALDO B. 2000121900360 DubaiPCG ABAD ARIANNE FAYE D. 2000016765000 PaRC ABAD MICHELLE JANE D. 2000135890360 DubaiPCG ABAD MA. LAVINIA R. 2000037215000 PaRC ABAD SARAH T. 2000037435000 PaRC ABAD GERALD E. 2000137190360 Dubai PCG ABAD PAOLO NOEL R. 2000038495000 PaRC ABADILLA JOJO A. 2000017505000 PaRC ABAGAT LILIA D. 2000037825000 PaRC ABALAYAN AUDREIL O. 2000017855000 PaRC ABALAYAN MILDRED O. 2000017865000 PaRC ABALLE JESIE FE S. 2000136280360 Dubai PCG ABALOS ARRA BELLA J. 2000019735000 PaRC ABALOS BLENS RADIEL S. 2000136930360 Dubai PCG ABALOS LIZA C. 2000037855000 PaRC ABALOS ALDRIN D. 2000038055000 PaRC ABALUS XYNE AUBRIELLE C. 2000124910360 DubaiPCG ABANICO DANILO JR. M. 2000106680360 DubaiPCG ABAO DANIEL V. 2000120610360 DubaiPCG ABAO MARY LYN A. -

THE BROOKLYN PHILHARMONIA 27Th Season: 1980/1981 LUKAS FOSS, Music Director

THEOOOPER~ONFORUM November 14, 1980, Spm THE BROOKLYN PHILHARMONIA 27th Season: 1980/1981 LUKAS FOSS, Music Director MEET THE MODERNS 1: MUSIC + DRAMA two one-act operas THE CRY OF CLYTAEMNESTRA THE EGG Music by John Eaton an operatic riddle Libretto by Patrick Creagh Music and Libretto by Gian Carlo Menotti New York premiere New York premiere RICHARD DUNCAN, conductor LUKAS FOSS, conductor Staging by Maurice Edwards Staging by Maurice Edwards Lighting by William Mintzer Lighting by William Mintzer Sound Co-ordinator: Lonnie Juli Costumes by Constance Mellen Cast Cast (in o rder of appearance) (in o rder of appearance) ClytaernJlt'~tra Quec•11 o{ Ar,J~e>S . elcla elson Manuel ................................... Martin Strother lphygene1a eldest dau,J~hter o{ C/ytaemnestra St Simeon Stylites .............................joseph Levitt !111(/ A.I!Cllll£'11111011 . • • • . • . • Sally Wolf BasJIJssa Empress o{ ByzantiUm ( Pnde} . ............ Edith Diggory Agamemnon KJII,JI of ArJioS . • . • • . Tim o ble Areobindus. {avonte o{the Bas111ssa (Lust} .......... Steven Nelson Ody~seus . Ri chard Walker Gourmantus, the cook (Gluttony} . ....... ........ Ted Adkins Menelaus . ·- . Brian Trego Eunuch of the Sacred Cubicle !Slot hi ............ Richard Walker DJOilll'tks . Martin Strother Pachomius. the treasurer (A vance} . .................. Jon Fay TnKer . Steven Nelson Sister of the BasJIJssa !Envyl . ...... ............... Paula Redd Calcha~. HlJih Pnest. joseph Levitt Julian, Capt am o{ the Guard (Anger} (silent role} . .. ..... Brian Trego Acl11llcs . .Jon Fay Beggar Woman . ... .............. Sarah Miller Electra. dauxhter o{ C/ytaem11estra and !Chorusl ............ Axamemncm. as a ch1ld . ................. .. ....... Abby Tate Members of the Basi IIssa's Court Sally Wolf, Martha Waltman Rebecca Field, Glenn Siebert, Colenton Freeman Orestes. so11 o{ Clytaem>lestra and Agamemnon, as a child . -

Jacob Lassetter, Baritone

JACOB LASSETTER, BARITONE With his powerful voice and commanding stage presence, baritone Jacob Lassetter enjoys an exciting and vibrant career on both the operatic and concert stage. Critics have praised his dignified characterizations, his soaring high range, and his deep, rich tone quality. In June 2021 Mr. Lassetter is excited to make his role and company debut as Scarpia in Tosca with Marble City Opera. Earlier in the 2020–2021 season he sings a solo recital of British composers and benefit concerts for both Winter Opera Saint Louis and Union Avenue Opera. Mr. Lassetter was scheduled to make his role and company debut as the title role in Der fliegende Holländer with Mid Ohio Opera, as well as a return to Italy for performances of the title role in Elijah, as soloist for Mozart’s Mass in C Minor, and various other concerts. These engagements were all unfortunately cancelled due to COVID-19. In the 2019–2020 season Mr. Lassetter sang Sonora in La fanciulla del West with Winter Opera Saint Louis, and both Schubert’s Winterreise and Argento’s The Andrée Expedition in recital. In the 2018–2019 season he sang Dr. Falke in Die Fledermaus with Winter Opera Saint Louis, Carmina Burana with the Washington University Symphony Orchestra, Verdi’s Requiem and A Symphony of Toys with The Missouri Symphony, Dick Deadeye in H.M.S. Pinafore and Il Gran Sacerdote in Nabucco with Union Avenue Opera, and a series of three recitals with St. Louis Art Song. Opera audiences have recently seen Mr. Lassetter as Sharpless in Madama Butterfly with Annapolis Opera, Wolfram in Tannhäuser with Apotheosis Opera (New York City), Peter in Hänsel und Gretel with Union Avenue Opera, and Rodrigo in the world premiere of Borgia Infami with Winter Opera Saint Louis. -

15, Mezzo-Soprano Denes Van Parys, Piano

SCHOOL OF MUSIC SENIOR RECITAL JENNIFER ANN MAYER ’15, MEZZO-SOPRANO DENES VAN PARYS, PIANO SUNDAY, MARCH 8, 2015 SCHNEEBECK CONCERT HALL 5 P.M. “Esurientes implevit bonis” ...................................................... Johann Sebastian Bach from Magnificat (1685–1750) “Lobe, Zion, deinen Gott” from Cantata No. 190 From Zwei Gesänge, Opus 91 ............................................................Johannes Brahms Geistliches Wiegenlied (1833–1897) with Forrest D. Walker, viola Nuit d’étoiles ........................................................................................ Claude Debussy (1862–1918) Le Spectre de la Rose ..............................................................................Hector Berlioz from Les Nuits d’Été (1803–1869) “Faites-lui mes aveux” ..........................................................................Charles Gounod from Faust (1818–1893) INTERMISSION From Sea Pictures, Opus 37 ...................................................................... Edward Elgar Where Corals Lie (1857–1934) Sabbath Morning at Sea “Lullaby” .......................................................................................... Gian Carlo Menotti from The Consul (1911–2007) “Il segreto per esser felici” ................................................................Gaetano Donizetti from Lucrezia Borgia (1797–1848) A reception will follow the recital in School of Music, Room 106. VOCALIST JENNIFER ANN MAYER ’15, mezzo-soprano, is double-majoring in music and communication studies. She studies voice -

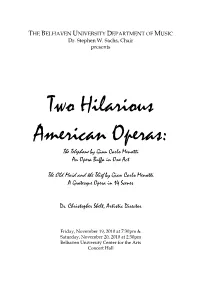

The Old Maid and the Thief by Gian Carlo Menotti a Grotesque Opera in 14 Scenes

THE BELHAVEN UNIVERSITY DEPARTMENT OF MUSIC Dr. Stephen W. Sachs, Chair presents Two Hilarious American Operas: The Telephone by Gian Carlo Menotti An Opera Buffa in One Act The Old Maid and the Thief by Gian Carlo Menotti A Grotesque Opera in 14 Scenes Dr. Christopher Shelt, Artistic Director Friday, November 19, 2010 at 7:30pm & Saturday, November 20, 2010 at 2:30pm Belhaven University Center for the Arts Concert Hall BELHAVEN UNIVERSITY DEPARTMENT OF MUSIC MISSION STATEMENT The Music Department seeks to produce transformational leaders in the musical arts who will have profound influence in homes, churches, private studios, educational institutions, and on the concert stage. While developing the God-bestowed musical talents of music majors, minors, and elective students, we seek to provide an integrative understanding of the musical arts from a Christian world and life view in order to equip students to influence the world of ideas. The music major degree program is designed to prepare students for graduate study while equipping them for vocational roles in performance, church music, and education. The Belhaven University Music Department exists to multiply Christian leaders who demonstrate unquestionable excellence in the musical arts and apply timeless truths in every aspect of their artistic discipline. The Music Department would like to thank our many community partners for their support of Christian Arts Education at Belhaven University through their advertising in “Arts Ablaze 2010-2011” (should be published and available on or before September 30, 2010). Special thanks tonight to Bo-Kays Florist for our reception table flowers. It is through these and other wonderful relationships in the greater Jackson community that makes an afternoon like this possible at Belhaven. -

April 2008 in This Issue

The Sacred in Opera April 2008 In this Issue... Ruth Dobson For the next two editions of the SIO newsletter, we are taking an in-depth look at one-act Christmas operas which can be easily produced and are appropriate for both children and adults. This issue we will profile Amahl and the Night Visitors, Only a Miracle, St. Nicholas, Good King Wenceslas, and The Shepherd’s Play. The next issue will highlight The Christmas Rose, The Greenfield Christmas Tree, The Finding of the King, The Night of the Star, and others. Thanks to Allen Henderson for sharing his insight into a triology of operas by Richard Shephard, Good King Wenceslas, The Shepherd’s Play, and St. Nicholas, with us in this issue. As great as Amahl and the Night Visitors is, there are these and other works waiting to be discovered by all of us. We hope you will find these suggestions interesting. These operas vary in length from 10 minutes to an hour, and can be presented alone or paired with others. Amahl and the Night Visitors is almost always a successful box office draw. Pairing it with a lesser known work could make for a very enjoyable afternoon or evening presentation and give audiences an opportunity to enjoy other equally wonderful works. Several of these operas use children as cast members, while others call for only adult performers, but all have stories appropriate for children. They are written in a variety of styles and have very different production requirements. Producers would need to take into consideration the ages of the children that are the target audience. -

Curriculum Vitae

CURRICULUM VITAE Gian Carlo Di Renzo, MD, PhD Professional Address Gian Carlo Di Renzo Professor and Chairman Dept. of Ob/Gyn Director, Centre for Perinatal and Reproductive Medicine Santa Maria della Misericordia University Hospital 06132 San Sisto - Perugia - Italy tel. +39 075 5783829 tel. +39 075 5783231 fax +39 075 5783829 [email protected] Date of birth: 13 June 1951 Place of birth: Verona, Italy Citizenship: Italian 1 Director of Education and Communication & Past General Secretary of FIGO University of Perugia, Perugia, Italy. Prof. Gian Carlo Di Renzo is currently Professor and Chair at the University of Perugia (2004 - ), and Director of the Reproductive and Perinatal Medicine Center (1996 - ) , former Director of the Midwifery School (2004-2016), University of Perugia, in addition to being the Director of the Permanent International and European School of Perinatal and Reproductive Medicine (PREIS) in Florence (2012 - ) . After graduation cum laude at Medical School of the University of Padova (1975) , he was a research fellow at the Universities of Verona, Messina and Modena. After training at CHUV in Lausanne (Switzerland), at UCH in London (UK), at the University of Texas in Dallas (USA), and at the Catholic University in Nijmegen (NL) (1977-1982), he became a senior researcher at the University of Perugia. Since 2004 he is Professor and Chairman of the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology at the University or Perugia., Chairman of the Midwifery School in the year 2004 to 2016, of the Ob Gyn Resident’s program since 2008 and of the PhD Program in Translational Medicine since 2012. He was general Secretary of the Italian Society of Perinatal Medicine, President of the Italian Society of Ultrasound in Obstetrics and Gynecology, Secretary-Treasurer of the European Association of Perinatal Medicine, President from 2000 to 2002, 2002-2008 Executive Director and Chairman of the Educational Committee, Vice President of the World Association of Perinatal Medicine ( 2007-2013) . -

Developing the Young Dramatic Soprano Voice Ages 15-22 Is Approved in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Of

DEVELOPING THE YOUNG DRAMATIC SOPRANO VOICE AGES 15-22 By Monica Ariane Williams Bachelor of Arts – Vocal Arts University of Southern California 1993 Master of Music – Vocal Arts University of Southern California 1995 A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Doctor of Musical Arts School of Music College of Fine Arts The Graduate College University of Nevada, Las Vegas December 2020 Copyright 2021 Monica Ariane Williams All Rights Reserved Dissertation Approval The Graduate College The University of Nevada, Las Vegas November 30, 2020 This dissertation prepared by Monica Ariane Williams entitled Developing the Young Dramatic Soprano Voice Ages 15-22 is approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts School of Music Alfonse Anderson, DMA. Kathryn Hausbeck Korgan, Ph.D. Examination Committee Chair Graduate College Dean Linda Lister, DMA. Examination Committee Member David Weiller, MM. Examination Committee Member Dean Gronemeier, DMA, JD. Examination Committee Member Joe Bynum, MFA. Graduate College Faculty Representative ii ABSTRACT This doctoral dissertation provides information on how to develop the young dramatic soprano, specifically through more concentrated focus on the breath. Proper breathing is considered the single most important skill a singer will learn, but its methodology continues to mystify multitudes of singers and voice teachers. Voice professionals often write treatises with a chapter or two devoted to breathing, whose explanations are extremely varied, complex or vague. Young dramatic sopranos, whose voices are unwieldy and take longer to develop are at a particular disadvantage for absorbing a solid vocal technique. First, a description, classification and brief history of the young dramatic soprano is discussed along with a retracing of breath methodologies relevant to the young dramatic soprano’s development. -

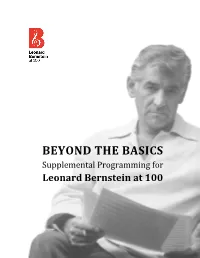

BEYOND the BASICS Supplemental Programming for Leonard Bernstein at 100

BEYOND THE BASICS Supplemental Programming for Leonard Bernstein at 100 BEYOND THE BASICS – Contents Page 1 of 37 CONTENTS FOREWORD ................................................................................. 4 FOR FULL ORCHESTRA ................................................................. 5 Bernstein on Broadway ........................................................... 5 Bernstein and The Ballet ......................................................... 5 Bernstein and The American Opera ........................................ 5 Bernstein’s Jazz ....................................................................... 6 Borrow or Steal? ...................................................................... 6 Coolness in the Concert Hall ................................................... 7 First Symphonies ..................................................................... 7 Romeos & Juliets ..................................................................... 7 The Bernstein Beat .................................................................. 8 “Young Bernstein” (working title) ........................................... 9 The Choral Bernstein ............................................................... 9 Trouble in Tahiti, Paradise in New York .................................. 9 Young People’s Concerts ....................................................... 10 CABARET.................................................................................... 14 A’s and B’s and Broadway ....................................................