Seasalter: a Problem Borough in Domesday Kent Re-Examined

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Prehistoric Settlement Patterns on the North Kent Coast Between Seasalter and the Wantsum

Archaeologia Cantiana Vol. 129 2009 PREHISTORIC SETTLEMENT PATTERNS ON THE NORTH KENT COAST BETWEEN SEASALTER AND THE WANTSUM TIM ALLEN The area of the north Kent coast addressed in the following study comprises the London Clay-dominated coastal flats, levels and low hills lying north of the Blean, west of the Wantsum Channel and east of Seasalter Level (Map 1). The area measures approximately 15km (10 miles) east-west and 4km (2½ miles) north-south, this representing 60km2. Archaeological remains dating from the Mesolithic to the Roman period were examined with the intention of determining whether significant changes in settlement/ occupation patterns could be discerned over this protracted period and, if so, whether the factors underlying those changes could be identified. A total of 32 sites were investigated and are listed below (Reculver, despite its Late Iron Age origin, has been excluded because of its largely military function during the Roman period, see Rivet and Smith 1981, 446-7; Philp 1959, 105). The statistical evidence derived from the sites is necessarily indicative rather than precise and, as new sites are constantly being uncovered, the list cannot be fully comprehensive. It is also probable that some of the sites represent parts of the same large, widespread settlements, others evidence of relatively transient occupation activity. Despite this it is proposed that the sample is large enough for significant conclusions to be drawn in terms of period-specific settlement activity and for new insights to be gained into the way settlement patterns have changed in the area over several thousand years. Background The archaeological potential of the study area was considered to be low until recently, probably because of its desolate and thinly settled nature during recent and historical times, as this description of the parish of Herne, in the eastern part of the coastal levels, makes clear: This parish is situated about six miles north-eastwards from Canterbury, in 189 TIM ALLEN Map. -

The Gild Merchant; a Contribution to British Municipal History

IdRONTO LIBRARY BINDING .L!?T JAN 1- 1925 THE GILD MERCHANT GKOSS VOL. I. HENRY FROWDE OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS WAREHOUSE AMEN CORNER, E.C. THE GILD MERCHANT A CONTRIBUTION TO ffiritisb Municipal CHARLES GROSS, PH. D. INSTRUCTOR IN HISTORY, HARVARD UNIVERSITY VOLUME I AT THE CLARENDON PRESS 1890 [ All rights reserved ] PRINTED AT THE CLARENDON PRESS BY HORACE HART, PRINTER TO THE UNIVERSITY HO v,; PREFACE. THIS book arose to some extent from the author's German ' doctoral dissertation, entitled Gilda Mercatoria' (Gottingen, 1883). The latter was based mainly on printed sources, and did not aim at exhausting the subject. The present work is based mainly on manuscript materials, and in it the author aspires to throw light on the development not merely of gilds but also of the municipal constitution. Much fresh and clas- sified material illustrating general municipal history will be found in the text and footnotes. " The shortcomings of many of the ordinary authorities on the history of gilds and boroughs are touched on in Vol. I. p. I, and in Appendix A. Appendix B (Anglo-Saxon Gilds) could not be dispensed with, inasmuch as many writers confuse Anglo-Saxon gilds with the Gild Merchant. The Scotch Gild Merchant and the Continental Gild Merchant (App. D and F) require separate treatment, because their development was different from that of the corresponding English institution, although most writers fail to notice this distinction. Appendix C (The English Hanse) and Appendix E (Affiliation of Boroughs) will, it is hoped, be as welcome to Continental as to English historians. The list of authorities at the end of Vol. -

Kent Archæological Society Library

http://kentarchaeology.org.uk/research/archaeologia-cantiana/ Kent Archaeological Society is a registered charity number 223382 © 2017 Kent Archaeological Society KENT ARCILEOLOGICAL SOCIETY LIBRARY SIXTH INSTALMENT HUSSEY MS. NOTES THE MS. notes made by Arthur Hussey were given to the Society after his death in 1941. An index exists in the library, almost certainly made by the late B. W. Swithinbank. This is printed as it stands. The number given is that of the bundle or box. D.B.K. F = Family. Acol, see Woodchurch-in-Thanet. Benenden, 12; see also Petham. Ady F, see Eddye. Bethersden, 2; see also Charing Deanery. Alcock F, 11. Betteshanger, 1; see also Kent: Non- Aldington near Lympne, 1. jurors. Aldington near Thurnham, 10. Biddend.en, 10; see also Charing Allcham, 1. Deanery. Appledore, 6; see also Kent: Hermitages. Bigge F, 17. Apulderfield in Cudham, 8. Bigod F, 11. Apulderfield F, 4; see also Whitfield and Bilsington, 7; see also Belgar. Cudham. Birchington, 7; see also Kent: Chantries Ash-next-Fawkham, see Kent: Holy and Woodchurch-in-Thanet. Wells. Bishopsbourne, 2. Ash-next-Sandwich, 7. Blackmanstone, 9. Ashford, 9. Bobbing, 11. at Lese F, 12. Bockingfold, see Brenchley. Aucher F, 4; see also Mottinden. Boleyn F, see Hever. Austen F (Austyn, Astyn), 13; see also Bonnington, 3; see also Goodneston- St. Peter's in Tha,net. next-Wingham and Kent: Chantries. Axon F, 13. Bonner F (Bonnar), 10. Aylesford, 11. Boorman F, 13. Borden, 11. BacIlesmere F, 7; see also Chartham. Boreman F, see Boorman. Baclmangore, see Apulderfield F. Boughton Aluph, see Soalcham. Ballard F, see Chartham. -

Mill House Blean

Archaeological Desk-Based Assessment in Advance of the Planning Application for a Proposed new dwelling at The Mill House, Tyler Hill Road, Blean, Kent February 2018 Archaeological Desk-Based Assessment in Advance of the Planning Application for a Proposed new dwelling at The Mill House, Tyler Hill Road, Blean, Kent. Report for Conker Conservation Ltd Date of Report: 8th Feb 2018 SWAT ARCHAEOLOGY Swale and Thames Archaeological Survey Company School Farm Oast, Graveney Road Faversham, Kent ME13 8UP Tel; 01795 532548 or 07885 700 112 www.swatarchaeology.co.uk The Mill House, Tyler Hill Road, Blean, Kent Archaeological Desk-Based Assessment Contents 1 INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................................. 5 1.1 Project Background ....................................................................................................5 1.2 The Site .......................................................................................................................5 1.3 The Proposed Development .......................................................................................5 1.4 Project Constraints .....................................................................................................6 1.5 Scope of Document ....................................................................................................6 2 PLANNING BACKGROUND .................................................................................................. 6 2.1 Introduction ................................................................................................................6 -

Community Network Profile Herne

Community network profile Herne Bay November 2015 Produced by Faiza Khan: Public Health Consultant ([email protected]) Wendy Jeffries: Public Health Specialist ([email protected]) Del Herridge, Zara Cuccu, Emily Silcock: Kent Public Health Observatory ([email protected]) Last Updated: 9th June 2016 | Contents 1. Executive Summary ................................................................ 5 1.1 Introduction................................................................................................................. 5 1.2 Key Findings ................................................................................................................. 5 2. Introduction & Objectives....................................................... 9 2.1 Community Network Area .......................................................................................... 9 2.1.1 Community Network ....................................................................................................... 9 3. Maternity ............................................................................. 10 3.1 Life expectancy at birth ............................................................................................. 10 3.1.1 Community network life expectancy trend .................................................................. 10 3.1.2 Ward level life expectancy ............................................................................................ 11 3.2 General fertility rate ................................................................................................. -

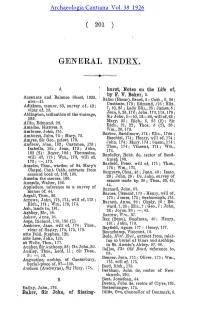

General Index

Archaeologia Cantiana Vol. 38 1926 ( 201 ) GENERAL INDEX. hurst, Notes on the Life of, Iby F. V. Baker, 5. Accounts and Balance Sheet, 1925, Baker (Bacar). Benet, 5 ; Oath., 6, 25: xlvi—li. Oustance. 173 ; Bdmond, 176 ; Eliz.. Adisham, manor, 83, survey of, 42; 7, 10, 25 ; Lady Eli/,., 25 ; James, 5 : vicar of, 23. Joan, 5,25,173; John. 173.175,178 ; Aldington, ordination of the vicarage, Sir John, 5—10, 12—26, will of, 25 ; 189. Mary, 25: Rich.. 5, 25 (2); Sir Allin, Edmund, 23. Rich., 21, 22; Thos., 5 (2), 25; Amadas, Mistress. 9. Wm., 26, 173. Ambrose, John, 175. Barbor, Bartilmew, 174 ; Elix., 174» ; Amhnrst. John, 73 ; Mary, 73. Ezechiel, 174; Henry, will of, 174 ; Amyee, Sir Geo.. priest, 178. John. 174 ; Mary. 174 ; Susan, 174 ; Andrew, Alan, 182; Oustance, 173; Thos., 174; Vincent, 174: Wm.. Isabella, 182; Joan, 173 ; John, 174. 182(2): Roger, 182; Thomasine, Bardelby, Robt. de, rector of Sand- •will of, 173 ; Wm., 173, will of, hurst, 189. 173 ; —, 173. Barfleld, Peter, will of, 175 ; Thos., Anselm, Thos., warden of St. Mary's 175; Wm,, 175. Ohapel, Cant. Oath., extracts from Hargrove, Chas., 43 ; Dean. 43 ; Isaac. account book of, 139, 160. 29 • John, 29 : Dr. John, survey of Anselm the mercer, IGli. estates made by, 29 ; Thos.. 33, 43, Anunde, Walter, 160. 44. Appledore. reference to a survey of Barnard, John, 57. manor of, 44. Barnes, Clement, 175 ; Henry, will of, Argall, Thos.. 25. 175 ; James, 175 ; Sexborough, 175. Arrowe, John, 173,174, will of. 173 ; Barrett, Anne, 26 ;• Cicely, 26 : Ed- Rich., 174 ; Wm., 173, 174. -

The Medieval English Borough

THE MEDIEVAL ENGLISH BOROUGH STUDIES ON ITS ORIGINS AND CONSTITUTIONAL HISTORY BY JAMES TAIT, D.LITT., LITT.D., F.B.A. Honorary Professor of the University MANCHESTER UNIVERSITY PRESS 0 1936 MANCHESTER UNIVERSITY PRESS Published by the University of Manchester at THEUNIVERSITY PRESS 3 16-324 Oxford Road, Manchester 13 PREFACE its sub-title indicates, this book makes no claim to be the long overdue history of the English borough in the Middle Ages. Just over a hundred years ago Mr. Serjeant Mere- wether and Mr. Stephens had The History of the Boroughs Municipal Corporations of the United Kingdom, in three volumes, ready to celebrate the sweeping away of the medieval system by the Municipal Corporation Act of 1835. It was hardly to be expected, however, that this feat of bookmaking, good as it was for its time, would prove definitive. It may seem more surprising that the centenary of that great change finds the gap still unfilled. For half a century Merewether and Stephens' work, sharing, as it did, the current exaggera- tion of early "democracy" in England, stood in the way. Such revision as was attempted followed a false trail and it was not until, in the last decade or so of the century, the researches of Gross, Maitland, Mary Bateson and others threw a fiood of new light upon early urban development in this country, that a fair prospect of a more adequate history of the English borough came in sight. Unfortunately, these hopes were indefinitely deferred by the early death of nearly all the leaders in these investigations. -

280 Faversham Road Seasalter Whitstable Kent CT5 4BN

Faversham Road, Seasalter, Whitstable 280 Faversham Road Seasalter Whitstable Kent CT5 4BN Description Ground Floor First Floor • Entrance Hall • Landing • Cloakroom • Bedroom 15'4 x 13'4 • Living Room (4.67m x 4.06m) 19'2 x 15'3 (5.84m x 4.65m) • En-suite Shower Room • Kitchen 14'7 x 12'10 • Bedroom (4.45m x 3.91m) 13'4 x 12'9 (4.06m x 3.89m) • Utility Room • En-suite Shower Basement Level Room • Cellar External 34'8 x 19'0 (10.57m x 5.79m) • Block-Paved Driveway Property A brand new individually designed detached two bedroom home just yards from the seafront. This delightful home has been thoughtfully designed and provides light, bright and contemporary living. The accommodation is arranged over three floors. To the ground floor there is a lounge with bi-fold doors leading to the large balcony to the rear enjoying uninterrupted views over the open countryside with far reaching views. The kitchen/diner to the front has integrated oven, hob, dishwasher and an American style fridge. There is also a Juliet balcony and sea views. There is also a useful utility room and a cloakroom. To the first floor there are two bedrooms, both enjoying fantastic views and each with Juliet balconies and en-suite shower rooms. To the lower ground floor there is a large open-plan room which cannot be used as bedroom accommodation but could provide a variety of uses including a gym or cinema room. Externally to the rear there is a large balcony ideal for entertainment and al-fresco dining, whilst to the front there is off street parking for two cars. -

A GROUP of MOUNDS on SEASALTER LEVEL, NEAR WHITSTABLE, and the MEDIEVAL IMBANKING in THIS AREA by M

Archaeologia Cantiana Vol. 70 1956 A GROUP OF MOUNDS ON SEASALTER LEVEL, NEAR WHITSTABLE, AND THE MEDIEVAL IMBANKING IN THIS AREA By M. W. THOMPSON THE origin of the mounds that are so commonly found on the marshes around the British Isles has always been a perplexing problem. The Essex Archaeological Society, it will be remembered, after several seasons' excavation on the Red Hills in the Essex marshes were unable to decide what activity had caused their accumulation, and it was only ten years later that Mr. R. A. Smith1 by the use of convincing Conti- nental parallels was able to show beyond reasonable doubt that they were the remains of salt works, where sea-water had been evaporated by an unfamiliar method. A few years later other members of this Society excavated further mounds, taller than the Red Hills, without briquetage and of Medieval date.2 They concluded they were salt works also, a view lent some support by the enclosures adjoining them. In the mounds we shall discuss below there was practically no briquetage and very little red earth; the mounds were clearly Medieval in date and not Roman or Iron Age like the Red Hills; and on Sheppey (within sight three miles away) the dialect word " coterells,"3 apparently of ancient origin, suggested that the mounds there may have been thrown up as refuges for cattle and sheep during tidal flooding. For these reasons we were reluctant to regard these mounds as salt works until the bulldozing of further intact mounds showed such frequent traces of burning that the conclusion became unavoidable that some industrial activity was involved. -

TEAM VICAR of ST ALPHEGE, SEASALTER and TEAM RECTOR

TEAM VICAR of ST ALPHEGE, SEASALTER and TEAM RECTOR of WHITSTABLE The Diocese of Canterbury welcomes applications for this exciting post as Team Rector of the Whitstable Team and Team Vicar of St Alphege Seasalter . We hope that the following profile gives you a sense both of the vibrant community of faith at Seasalter and also a flavour of the life and witness of the other Churches in the team. By way of background, this Team ministry was set up in 1984. The way that the roles were described in the team are as follows: ‘The cure of souls of that area shall be shared by the incumbent of the Benefice, whose office shall be that of rector in the team ministry, and three other ministers, each of whom shall have the title vicar and a status equal to that of an incumbent of a benefice.’ Please don’t hesitate to contact me if you would like to discuss this opportunity and please be assured of our prayers as you consider whether God is calling you to be part of this ministry. The Venerable Jo Kelly-Moore Archdeacon of Canterbury [email protected] Contents Our Vision, Purpose and Values .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. Page 4 Our church .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. Page 5. Who we are seeking .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. Page 6. Our Town .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. Page 7. Worship .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. Page 8. Prayer .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. Page 9. What sort of church are we? .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. Page 10. What are we like? .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. Page 11. What else do we do? .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. Page 13. Leadership .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. Page 14. Staff Team .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. Page 15. Children and Families Ministry .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. .. Page 16. Youth Ministry and Twenties . -

Reports Series Pre 1977

LIST OF UNPUBLISHED FIELDWORK REPORTS HELD BY CANTERBURY ARCHAEOLOGICAL TRUST The following reports (so-called ©grey literature©) may be viewed by appointment only at: Canterbury Archaeological Trust 92a Broad Street Canterbury Kent CT1 2LU telephone: 01227 462062 email: [email protected] CANTERBURY ARCHAEOLOGICAL TRUST Archaeological Reports Scope of the List The following list is intended to provide a bibliographic guide to all reports that have been deposited in the Canterbury Archaeological Trust library. The arrangement is by year date of compilation. Reports have been given an individual number within each year date. The reports can be found in magazine files in the library likewise arranged by year date and report number. The following information is given for each report: 1 report number 2 location 3 type of development 4 type of archaeological intervention 5 national grid references 6 start and end dates of field/desk work 7 type of report 8 pagination and contents 9 name(s) of compiler 10 issuing institution 11 date of publication 12 site code 13 archive number 14 name of museum (Canterbury = CCM) and accession number Note that the list includes all reports received, not only those compiled in-house. Reports produced by the Oxford Archaeological Unit (OAU), Museum of London Archaeology Service (MoLAS14568), Wessex Archaeology, South-East Archaeology Service (SEAS) as well as other archaeological, historical and heritage organizations are included on the list. The relevant site codes and internal archive/report numbers of these reports have also been cited where known. Other Sources Reports produced by CAT during 1995 and 1996 which have been abstracted for inclusion in the supplement to the CBA Bibliography published in 1999 are indicated by an asterisk against the report number. -

Mile NE, Near "Which Is Hunter's Forstall-One Part

218 BLEANGATE HUNDRED. vijlage one mile N.-BnooMFIELD, a small village I! mile N.E., near "Which is Hunter's Forstall-one part of Broomfield stands in the parish ()f Reculver. THE BLEAN POOR LAW UNION is situated on Herne Common, about 11alf 8 mile from the church, and was erected in 1836, at a cost of £6,300 ~t is a spacious brick building, forming a quadrangle, having an inter section across the centre, and will accommodate 420 inmates. The union comprises a district of 16 parishes, with an area of 27.034 acres, and a population of 14,387 souls. The parishes are Archbishop's Palace, Bleau, 'Chislet, (Christ Church, St. Dunstan, St. Gregory, St. Stephen, Hoath Rerne, R'3culver, Staplegate, Seasalter, Sturry, Swalcliffe, Westbere, and Whitstable; for which] 9 guardians are elected, who meet every Thurs· day at the Board-room. Chairman, George Goddard, Esq.; Clerk, Mr. Wm. Sladden; Surgeons, Mr. Wm. Evans, Herne, Mr. J. E. C. Williams, Whitstable, and Mr. Thomas Andrew, Canterbury; Relieving Officers, Mr Pope :and Mr. Pilcher; Chaplain, Rev. Wm. Temple; Governor and Matron, Henry and Maria Church; Registrars of Births and Deaths, Wm. Evans, J. E. C. Williams, and H. Hills; of Marriages, Alfred Trew, Herne Bay; 8upeTintendallt Registrar, George Heath, Canterbury; Schoolmaster Richard Coleman; Schoolmistress, Elizabeth SewdI. HERNE BAY, a delightful and fcshionable watering place, is situated 'between Whitstable and Reenlver, Si miles N. from Canterbury, 15 mile'! W. from Margate, 17 miles W. b N. from Ramsgate, and 24 miles N. b 'Wo from Dover. The town is built on a gentle elevation, commanding J.