Interview with Interviewee Roy Wehrle # VRV-A-L-2013-098.05

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Y 2 0 ANDRE MALRAUX: the ANTICOLONIAL and ANTIFASCIST YEARS DISSERTATION Presented to the Graduate Council of the University Of

Y20 ANDRE MALRAUX: THE ANTICOLONIAL AND ANTIFASCIST YEARS DISSERTATION Presented to the Graduate Council of the University of North Texas in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY By Richard A. Cruz, B.A., M.A. Denton, Texas May, 1996 Y20 ANDRE MALRAUX: THE ANTICOLONIAL AND ANTIFASCIST YEARS DISSERTATION Presented to the Graduate Council of the University of North Texas in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY By Richard A. Cruz, B.A., M.A. Denton, Texas May, 1996 Cruz, Richard A., Andre Malraux: The Anticolonial and Antifascist Years. Doctor of Philosophy (History), May, 1996, 281 pp., 175 titles. This dissertation provides an explanation of how Andr6 Malraux, a man of great influence on twentieth century European culture, developed his political ideology, first as an anticolonial social reformer in the 1920s, then as an antifascist militant in the 1930s. Almost all of the previous studies of Malraux have focused on his literary life, and most of them are rife with errors. This dissertation focuses on the facts of his life, rather than on a fanciful recreation from his fiction. The major sources consulted are government documents, such as police reports and dispatches, the newspapers that Malraux founded with Paul Monin, other Indochinese and Parisian newspapers, and Malraux's speeches and interviews. Other sources include the memoirs of Clara Malraux, as well as other memoirs and reminiscences from people who knew Andre Malraux during the 1920s and the 1930s. The dissertation begins with a survey of Malraux's early years, followed by a detailed account of his experiences in Indochina. -

Vietnam Songs 1960’S-1970’S

Group Members Names _________________________________ ________________________________ _________________________________ Vietnam Songs 1960’s-1970’s Directions: 1. As a group find the lyrics to the assigned song. 2. Go over lyrics as a group and discuss what the song means. 3. Break down the given song and write your groups interpretation of the lines or verse (directly on the printed song). 4. Find the music to the song to play for the class. Present interpretation. 5. Ex-credit connect a current song to times in America today. Do steps 1-5 Circle Assigned Song Ballad of Green Berets – Barry Sadler 66’ Volunteers – Jefferson Airplane 69’ Blowin in the Wind- Bob Dylan 62’ Fortunate Son-Credence Clearwater Revival 69’ I Feel Like I’m Fixin to Die – Joe Mc. Donald 65’ It Better End Soon- Chicago 70’ Price of Paradise – Minutemen War- Edwin Star 69’ What’s Going On- Marvin Gaye 71’ You Haven’t Done Nothin- Steve Wonder 74’ The Unknown Solider – Doors 68’ Eve of Destruction- Barry Mcguire Gimme Shelter- Rollin Stones 69’ Imagine - John Lennon Eighteen – Alice Cooper Machine Guns – Jimi Hendrix Born in the USA- Bruce Springsteen No Expectations – Rolling Stones Still in Saigon- Charlie Daniels Ball of Confusion (That’s What the World Is Today) - Temptations 70’ Ballad Of The Green Berets As Written & Performed by SSgt Barry Sadler Fighting soldiers from the sky Fearless men who jump and die Men who mean just what they say The brave men of the Green Beret Silver wings upon their chest These are men, America's best One hundred men we'll test -

Goodnight Saigon: Billy Joel’S Musical Epitaph to the Vietnam War

Touro Law Review Volume 32 Number 1 Symposium: Billy Joel & the Law Article 5 April 2016 Goodnight Saigon: Billy Joel’s Musical Epitaph to the Vietnam War Morgan Jones Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.tourolaw.edu/lawreview Part of the Law Commons, and the Other Music Commons Recommended Citation Jones, Morgan (2016) "Goodnight Saigon: Billy Joel’s Musical Epitaph to the Vietnam War," Touro Law Review: Vol. 32 : No. 1 , Article 5. Available at: https://digitalcommons.tourolaw.edu/lawreview/vol32/iss1/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ Touro Law Center. It has been accepted for inclusion in Touro Law Review by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ Touro Law Center. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Jones: Goodnight Saigon GOODNIGHT SAIGON: BILLY JOEL’S MUSICAL EPITAPH TO THE VIETNAM WAR Morgan Jones* Billy Joel adopted new personae and took on new roles in several songs on both 1982’s The Nylon Curtain1 and his penultimate studio album to date, 1989’s Storm Front.2 In what some have seen as an attempt to reach a more adult audience, to “move pop/rock into the middle age and, in the process, earn critical respect,”3 Joel put on new hats (literally, at times: his fedora-wearing balladeer appears prominently in the video for “Allentown”) for “Allentown” and “The Downeaster ‘Alexa’,” “Pressure” and “We Didn’t Start the Fire,” and “Goodnight Saigon” and “Leningrad.”4 Each of these pairs of songs saw Joel endeavoring to make statements about issues that were bigger than he and his own life, which was in stark contrast to his sources of inspiration for his earlier, more self-centered albums. -

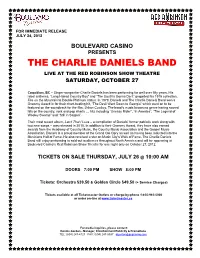

The Charlie Daniels Band

22 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE JULY 24, 2012 BOULEVARD CASINO PRESENTS THE CHARLIE DANIELS BAND LIVE AT THE RED ROBINSON SHOW THEATRE SATURDAY, OCTOBER 27 Coquitlam, BC – Singer-songwriter Charlie Daniels has been performing for well over fifty years. His rebel anthems, “Long Haired Country Boy” and “The South’s Gonna Do It” propelled his 1975 collection, Fire on the Mountain to Double Platinum status. In 1979, Daniels and The Charlie Daniels Band won a Grammy Award in for their chart-busting hit, “The Devil Went Down to Georgia” which went on to be featured on the soundtrack for the film, Urban Cowboy. The band’s music knows no genre having scored hits on the country, rock and pop charts … hits including “Uneasy Rider”, “In America”, “The Legend of Wooley Swamp” and “Still in Saigon”. Their most recent album, Land That I Love – a compilation of Daniels’ former patriotic work along with two new songs – was released in 2010. In addition to their Grammy Award, they have also earned awards from the Academy of Country Music, the Country Music Association and the Gospel Music Association. Daniels is a proud member of the Grand Ole Opry as well as having been inducted into the Musicians Hall of Fame. He also received a star on Music City’s Walk of Fame. The Charlie Daniels Band still enjoy performing to sold-out audiences throughout North America and will be appearing at Boulevard Casino’s Red Robinson Show Theatre for one night only on October 27, 2012. TICKETS ON SALE THURSDAY, JULY 26 @ 10:00 AM DOORS 7:00 PM SHOW 8:00 PM Tickets: Orchestra $39.50 & Golden Circle $49.50 (+ Service Charges) Tickets available at all Ticketmaster Outlets or charge-by-phone 1-855-985-5000 or order on-line at www.ticketmaster.ca For media inquiries, please contact: Donnie Gordon - Manager, Entertainment Publicity & Promotions TEL: (604) 247-4127 FAX: (604) 247-8587 [email protected] . -

DJ Song List by Song

A Case of You Joni Mitchell A Country Boy Can Survive Hank Williams, Jr. A Dios le Pido Juanes A Little Bit Me, a Little Bit You The Monkees A Little Party Never Killed Nobody (All We Got) Fergie, Q-Tip & GoonRock A Love Bizarre Sheila E. A Picture of Me (Without You) George Jones A Taste of Honey Herb Alpert & The Tijuana Brass A Ti Lo Que Te Duele La Senorita Dayana A Walk In the Forest Brian Crain A*s Like That Eminem A.M. Radio Everclear Aaron's Party (Come Get It) Aaron Carter ABC Jackson 5 Abilene George Hamilton IV About A Girl Nirvana About Last Night Vitamin C About Us Brook Hogan Abracadabra Steve Miller Band Abracadabra Sugar Ray Abraham, Martin and John Dillon Abriendo Caminos Diego Torres Absolutely (Story Of A Girl) Nine Days Absolutely Not Deborah Cox Absynthe The Gits Accept My Sacrifice Suicidal Tendencies Accidentally In Love Counting Crows Ace In The Hole George Strait Ace Of Hearts Alan Jackson Achilles Last Stand Led Zeppelin Achy Breaky Heart Billy Ray Cyrus Across The Lines Tracy Chapman Across the Universe The Beatles Across the Universe Fiona Apple Action [12" Version] Orange Krush Adams Family Theme The Hit Crew Adam's Song Blink-182 Add It Up Violent Femmes Addicted Ace Young Addicted Kelly Clarkson Addicted Saving Abel Addicted Simple Plan Addicted Sisqó Addicted (Sultan & Ned Shepard Remix) [feat. Hadley] Serge Devant Addicted To Love Robert Palmer Addicted To You Avicii Adhesive Stone Temple Pilots Adia Sarah McLachlan Adíos Muchachos New 101 Strings Orchestra Adore Prince Adore You Miley Cyrus Adorn Miguel -

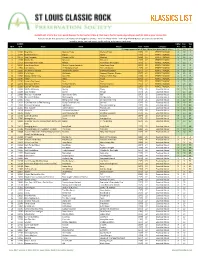

KLASSICS LIST Criteria

KLASSICS LIST criteria: 8 or more points (two per fan list, two for U-Man A-Z list, two to five for Top 95, depending on quartile); 1984 or prior release date Sources: ten fan lists (online and otherwise; see last page for details) + 2011-12 U-Man A-Z list + 2014 Top 95 KSHE Klassics (as voted on by listeners) sorted by points, Fan Lists count, Top 95 ranking, artist name, track name SLCRPS UMan Fan Top ID # ID # Track Artist Album Year Points Category A-Z Lists 95 35 songs appeared on all lists, these have green count info >> X 10 n 1 12404 Blue Mist Mama's Pride Mama's Pride 1975 27 PERFECT KLASSIC X 10 1 2 12299 Dead And Gone Gypsy Gypsy 1970 27 PERFECT KLASSIC X 10 2 3 11672 Two Hangmen Mason Proffit Wanted 1969 27 PERFECT KLASSIC X 10 5 4 11578 Movin' On Missouri Missouri 1977 27 PERFECT KLASSIC X 10 6 5 11717 Remember the Future Nektar Remember the Future 1973 27 PERFECT KLASSIC X 10 7 6 10024 Lake Shore Drive Aliotta Haynes Jeremiah Lake Shore Drive 1971 27 PERFECT KLASSIC X 10 9 7 11654 Last Illusion J.F. Murphy & Salt The Last Illusion 1973 27 PERFECT KLASSIC X 10 12 8 13195 The Martian Boogie Brownsville Station Brownsville Station 1977 27 PERFECT KLASSIC X 10 13 9 13202 Fly At Night Chilliwack Dreams, Dreams, Dreams 1977 27 PERFECT KLASSIC X 10 14 10 11696 Mama Let Him Play Doucette Mama Let Him Play 1978 27 PERFECT KLASSIC X 10 15 11 11547 Tower Angel Angel 1975 27 PERFECT KLASSIC X 10 19 12 11730 From A Dry Camel Dust Dust 1971 27 PERFECT KLASSIC X 10 20 13 12131 Rosewood Bitters Michael Stanley Michael Stanley 1972 27 PERFECT -

Brevard Live October 2006

Brevard Live October 2006 - 2 - Brevard Live October 2006 Brevard Live October 2006 - - Brevard Live October 2006 Brevard Live October 2006 - 6 - Brevard Live October 2006 BLMarch series 4, 1953 - THOSE WERE PART XIII August 20, 2005 as “Bruce Springsteen” and “The Eagles”), John The Glory Days Lane (bass), Hank Saunders HHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHH by Judy Tatum Lane (drums), Joe Billington (guitar) and Jim Nash (also on guitar). They practiced as a Marine in Vietnam, than carrying a rifle in a war s the saying goes, “it at the Lane’s house (as did who has spoken about just which had reached its peak. was the best of times, so many other musicians A how much the music meant it was the worst of times”. including Dave Fiester), to those who had found For me that is definitely the played local teen centers and themselves thousands of The Doors and 60’s. Such a bitter sweet attended school. time combined with so many miles away from home in a situation that to this day Rolling Stones radical things and changes in Their play list consisted doesn’t seem real, but at every aspect, all happening played on everyone’s of the great songs of the times seems only too real. at warp speed. Not just in era by bands who definitely The Doors and Rolling transistor radio that my life as a typical high reflected the times. Groups Stones played on everyone’s school student, but society had one... such as “The Doors”, transistor radio that had one. as a whole. As for the music “Rolling Stones”, “Jimi It entertained them, helped scene, I can’t think of any Hendrix”, and the “Chambers keep their sanity, and made During the same period, other time when music Brothers” just to mention a them feel closer and tied to here in Brevard County, played such an important few, with Robbin using drum home. -

Country Update

Country Update BILLBOARD.COM/NEWSLETTERS JULY 6, 2020 | PAGE 1 OF 22 INSIDE BILLBOARD COUNTRY UPDATE [email protected] Bryan Has ‘One’ What’s New? HARDY, McCollum, Quick ‘Margarita’ >page 4 Hammack Prep National Debut Projects Charlie Daniels Anyone who thinks country music occupies a narrow band in exhibiting a country tone and spunk that compare favorably Remembered the stylistic universe would do well to check out some of the to Carly Pearce and Jana Kramer. Ellis has dropped one self- >page 12 new artists on the way in the last half of 2020. funded EP prior to her forthcoming Nashville label debut, and Rock-edged HARDY and Tim Montana, pop-leaning Noah she also landed a cut on the Teen Wolf soundtrack. Schnacky, Texas-bred Parker McCollum and emotionally raw • Filmore (Curb) — Percolating rhythms and old-school Caylee Hammack comprise a good chunk of the next group pop melodies are the norm for Filmore and his passionate Jimmie Allen Gets of acts with their first albums or EPs for a major label or top tenor. A Wildwood, Mo., native, he honed his chops while Paired Up indie on the way. working the college circuit and built an online presence >page 14 Many of the sounds arriving at the moment might not have on his way to a Curb deal. His first full album for an estab- been accepted in another age, though the genre is constantly lished label, State I’m In, is expected Oct. 30, following a new evolving, reflecting the changing single mid-August. influences of its artists and its audi- • Ryan Griffin (Altadena/ ACM Wine Party With ences. -

Songs by Artist

TJ's Absolute Sound Songs by Artist 578-7576 Title Title Title - CASTILLOS EN EL AI (GOSPEL) LYNN, LORETTA 02 SHOWADDYWADDY ! PRECIOUS MEMORIES PRETTY LITTLE ANGEL EYES ABRAMZON, RAUL- UNA VIEJO SWING LOW SWEET CHAROIT 02 Taylor Swift CANCION DE AMOR WHEN THE ROLL IS CALLED UP You Belong With Me (CHRISTMAS) BROOKS & DUNN YONDER 03 BEAUTIFUL EYES HANGIN' 'ROUND THE WILL THE CIRCLE BE TAYLOR SWIFT MISTLETOE UNBROKEN 03 BLONDIE IT WON'T BE CHRISTMAS WINGS OF A DOVE TIDE IS HIGH WITHOUT YOU (POP MIX) -TAYLOR SWIFT 03 Drive Your Truck (CHRISTMAS) JACKSON, ALAN TEARDROPS ON MY GUITAR Lee Brice LET IT BE CHRISTMAS +44 03 Elvis Presley (CHRISTMAS) JUDD, CLEDUS T. WHEN YOUR HEART STOPS Mr. SongmanElvis Presley T BEATING 03 Ne-Yo TREE'S ON FIRE 01 BEYONCE Mac (CHRISTMAS) JUDDS SINGLE LADIES 03 SHOWADDYWADDY BEAUTIFUL STAR OF 01 BLONDIE HEY ROCK AND ROLL BETHLEHEM HEART OF GLASS 03 Spotlight (CHRISTMAS) KEITH, TOBY 01 Downtown Jennifer Hudson CHRISTMAS ROCK Lady Antebellum 03 Taylor Swift (CHRISTMAS) SHEDAISY 01 Elvis Presley Crazier SANTA'S GOT A BRAND NEW Loving ArmsElvis Presley BAG 03 VERONICAS 01 Kelly Clarkson (CHRISTMAS) STRAIT, GEORGE UNTOUCHED My Life World Suck Without You MERRY CHRISTMAS 04 AKON 01 SAY AAH (WHEREVER YOU ARE) RIGHT NOW TREY SONGZ SANTA'S ON HIS WAY 04 BLONDIE 01 SHOWADDYWADDY (CHRISTMAS) TIPPIN, AARON RAPTURE UNDER THE MOON OF LOVE IT'S WAY TOO CLOSE TO 04 BREAK YOUR HEART 01 Womanizer CHRISTMAS TO BE THIS FAR TAIO CRUZ Britney Spears (CHRISTMAS) TRACTORS 04 Elvis Presley 02 BLONDIE BOOGIE WOOGIE SANTA There Goes My Everything -

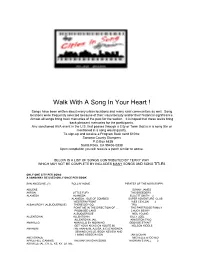

Walk with a Song in Your Heart !

Walk With A Song In Your Heart ! Songs have been written about many urban locations and many rural communities as well. Song locations were frequently selected because of their visual beauty and/or their historical significance. Almost all songs bring back memories of the past for the walker. It is hoped that these walks bring back pleasant memories for the participants. Any sanctioned AVA event in the U.S. that passes through a City or Town that is in a song title or mentioned in a song would qualify. To sign-up and receive a Program Book send $10 to: Sonoma County Stompers P.O.Box 6838 Santa Rosa, CA 95406-0838 Upon completion you will receive a patch similar to above. BELOW IS A LIST OF SONGS CONTRIBUTED BY TERRY WAY WHICH MAY NOT BE COMPLETE BY INCLUDES MANY SONGS AND SONG TITLES ONLY ONE CITY PER SONG A SONG MAY BE USED ONLY ONCE PER BOOK SAN ANGELINE, (?) ROLLIN’ HOME PIRATES OF THE MISSISSIPPI ABILENE SONNY JAMES AKRON LITTLE FURY THE BREEDERS ALAMEDA ALAMEDA ELLIOTT SMITH 2 ALAMEDA: ISLE OF ZOMBIES SUPER ADVENTURE CLUB WESTERN FRONT WES CEYLON 2 ALBAKURCKY (ALBUQUERQUE) THERE DEY GO TRU POINT ME IN THE DIRECTION OF … THE PARTRIDGE FAMILY PROMISED LAND CHUCK BERRY ALBUQUERQUE NEIL YOUNG ALLENTOWN ALLENTOWN BILLY JOEL ALLENTOWN JAIL KINGSTON TRIO AMARILLO AMARILLO BY MORNING GEORGE STRAIT GET YOUR KICKS ON ROUTE 66 NELSON RIDDLE ANAHEIM THE ANAHEIM, AZUSA, & CUCAMONGA SEWING CIRCLE, BOOK REVIEW AND TIMING ASSOCIATION JAN & DEAN ANCHORAGE MICHELLE sHOCKED APPLE HILL (CAMINO) THE MARTINTOWN SONG HADRIAN’S WALL 2 ASHVILLE (AL, CA, -

Vietnamkrigens Sange

The Songs of the Vietnam War Collected and documented by Holger Terp, The Danish Peace Academy Vietnamkrigens sange Samlet og dokumenteret af Holger Terp, Det danske Fredsakademi 2 Fredssange Saks eller skriv den sangtitel du er interesseret i, ind i din favorit søgemaskine eller i You Tube, så vil det for en stor dels vedkommende være muligt, at høre musikken. Peace Songs Cut or write the song title you're interested in, into your favorite search engine or You Tube, so will it to a large extent be possible to hear the music. Chansons de la paix Couper ou écrire le titre de la chanson qui vous inté- resse, dans votre moteur de recherche favori ou You Tube, ainsi il dans une large mesure être possible d'en- tendre la musique. Lieder des Friedens Ausschneiden oder schreiben Sie die Liedtitel, der Sie in- teressiert, in Ihrem Lieblings–Suchmaschine oder You Tube, so wird es zu einem großen Teil möglich sein, die Musik zu hören. 3 4 Indholdsfortegnelse The Vietnam War.........................................................................................................8 Don't Burn It..............................................................................................................11 Dodging the Draft......................................................................................................12 Vietnamkrigen............................................................................................................16 Quand un soldat.........................................................................................................22 -

Catalog 2009

YAMAHA MUSICSOFT 2009 Performance and interactive software for Yamaha Disklavier, Clavinova, Portable Keyboards, and other MIDI-capable devices CATALOG 2009 +84088-CBIAIj HL90005658 59969 09 Yamaha Cat Guts: 12/11/08 3:24 PM Page fic1 BEST SELLERS 1. Frank Sinatra Collection – “My Way” . 00501992 2. Nat King Cole Collection – “Unforgettable” . 00503314 3. Mannheim Steamroller Christmas . 00501990 4. “Bridge over Troubled Water” – Simon & Garfunkel . 00503358 5. “Endless Love” – Lionel Richie. 00503372 6. The Best of Barry Manilow . 00503342 7. The Stevie Wonder Collection . 00503339 8. “More Than a Feeling” – Smooth Pop . 00506315 9. The Phantom of the Opera . 00504606 10. “You’ve Got a Friend” – Carole King . 00503371 1. The Romance of Jim Brickman. 00506320 2. David Garfield and the Monster Trio . 00506341 1. The Best of Elton John . 00501214 3. Classical Favorites. 00503484 2. Love Songs of Lennon & McCartney . 00501219 4. Edith Piaf – A Tribute! . 00503460 3. The Best of Chicago . 00501215 5. Love in the ’80s and ’90s. 00503414 4. “Phantom of the Opera” – Selections . 00501076 6. “Anything Goes” – Cole Porter . 00506318 5. Gershwin Plays Gershwin. 00501189 7. Best of Creedence Clearwater Revival . 00503413 6. All Time Requests. 00501032 8. “Hey Girl” & Hits of the ’60s/’70s . 00503381 7. Piano Encore . 00501016 9. Rhythm Is Gonna Get You . 00503440 8. Andrew Lloyd Webber Favorites – “Sunset Boulevard” . 00501192 10. April in Paris – Count Basie . 00503418 9. Debussy Piano Works. 00501220 10. “Les Miserables” . 00501111 1. Mamma Mia! – The Musical. 00504158 2. The Beatles – 1 . 00503610 1. Christmas Lights (StarLIGHTS) . 00505809 3. Frank Sinatra – Reprise: The Very Good Years. 00503446 2.