1853 Cornwall Quarter Sessions and Assizes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

P O L T a I R H O M E S - C O R N W a L L Padstow...A Historic and Friendly Cornish Community

P O L T A I R H O M E S - C O R N W A L L Padstow...a historic and friendly Cornish community Padstow and the coastal area around is a hugely desirable location with golden sandy Lefra Orchard, St Buryan. Victoria Gardens, Camelford. beaches, a beautiful estuary, fascinating wildlife, high cliffs, rocky coves, thundering surf and endless wonderful views. Leisure pursuits abound, including sailing, Poltair Homes surfing, water skiing, coasteering, wind . a heritage and kite surfing, golf, horse riding, cycling and walking the famous Camel Trail or of creating the South West Coastal Path as it passes homes through the area. in Cornwall For many years there have been only a Cooperage Gardens, Trewoon. Lefra Orchard, St Buryan. limited number of new homes built in Padstow, which is why Poltair Homes Victoria Gardens, Camelford. Lefra Orchard, St Buryan. are so delighted to be creating new 2, 3 and 4 bedroom homes at Trecerus Farm. Conveniently located on the outskirts of the main hustle and bustle of the town, this is an opportunity to buy a new home, built to the high standards for which Poltair Homes have become so well respected, combined with contemporary finishes and energy saving features for your comfort and convenience. Enduringly charming laid back way of life Victoria Gardens, Camelford. Penvearn View, Cubert. 54 53 53 44 45 47 48 53 52 51 51 50 50 49 48 49 44 45 54 46 67 66 46 54 65 66 67 52 47 65 67 66 52 65 55 64 64 55 63 62 63 63 64 62 56 60 public 57 57 open space 62 60 Site plan Plots 46 - 67 56 59 58 61 Penrose 4 bed house with en-suite & study 59 57 58 61 Burlawn 3 bed house with en-suite play area Polpennic Drive 60 Trevose 3 bed house with en-suite 58 59 Tolcarne 3 bed house with en-suite Merryn 3 bed house with en-suite Treyarnon 3 bed house with en-suite Endellion 3 bed house with en-suite N Tredinnick 2 bed house with en-suite Garage Trewornan 2 bed house trecerus farm PADSTOW CORNWALL Site plan not to scale and for illustrative purposes only. -

Three Harbours) 2019

17/04/2019 Introduction Introducon Fowey (Three Harbours) 2019 The Three Harbours working area stretches from Fowey Westwards to Par and Northwards towards Key Messages the A30 and A38 encompassing Lostwithiel. Fowey Community Hospital is temporarily closed. 3 GP pracces, 2 of which are dispensing St Austell Community Hospital provides inpaent 19,470 residents are registered at the GP Pracces care and a range of clinics to people in the local area. Nearly 8,000 residents registered at Fowey River Pracce Bodmin Community Hospital provides physical and Obesity is the worst long term condion mental health care services to people in Bodmin and the surrounding area. 28.5% of paents are elderly Both St Austell and Bodmin Minor Injury Units are Currently 250 care home beds, 135 new units planned open daily 8am-10pm. The main general hospital for Cornwall, Royal Cornwall Hospitals NHS Trust, based in Treliske, Truro. 19,470 12.18% Registered Paents Paents Obese GP Pracces Name Address Town Postcode Status/Dispensing FOWEY RIVER PRAC RAWLINGS LANE FOWEY PL23 1DT Pracce - Disp 135 28.5% LOSTWITHIEL SURGERY NORTH STREET LOSTWITHIEL PL22 0EF Pracce - Disp Paents MIDDLEWAY SURGERY ST.BLAZEY PAR PL24 2JL Pracce - Non Disp Care Home Units Planned 65+ Introducon Populaon Elderly Populaon 1/1 17/04/2019 Population Populaon Three Harbours 2019 The latest figures (2017) show that the populaon for the Three Harbours working area is 20,000, with a difference of approximately 700 more female than male. The highest percentage of the populaon (1) is esmated to be in the 45-74 year age group. -

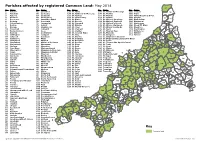

Parish Boundaries

Parishes affected by registered Common Land: May 2014 94 No. Name No. Name No. Name No. Name No. Name 1 Advent 65 Lansall os 129 St. Allen 169 St. Martin-in-Meneage 201 Trewen 54 2 A ltarnun 66 Lanteglos 130 St. Anthony-in-Meneage 170 St. Mellion 202 Truro 3 Antony 67 Launce lls 131 St. Austell 171 St. Merryn 203 Tywardreath and Par 4 Blisland 68 Launceston 132 St. Austell Bay 172 St. Mewan 204 Veryan 11 67 5 Boconnoc 69 Lawhitton Rural 133 St. Blaise 173 St. M ichael Caerhays 205 Wadebridge 6 Bodmi n 70 Lesnewth 134 St. Breock 174 St. Michael Penkevil 206 Warbstow 7 Botusfleming 71 Lewannick 135 St. Breward 175 St. Michael's Mount 207 Warleggan 84 8 Boyton 72 Lezant 136 St. Buryan 176 St. Minver Highlands 208 Week St. Mary 9 Breage 73 Linkinhorne 137 St. C leer 177 St. Minver Lowlands 209 Wendron 115 10 Broadoak 74 Liskeard 138 St. Clement 178 St. Neot 210 Werrington 211 208 100 11 Bude-Stratton 75 Looe 139 St. Clether 179 St. Newlyn East 211 Whitstone 151 12 Budock 76 Lostwithiel 140 St. Columb Major 180 St. Pinnock 212 Withiel 51 13 Callington 77 Ludgvan 141 St. Day 181 St. Sampson 213 Zennor 14 Ca lstock 78 Luxul yan 142 St. Dennis 182 St. Stephen-in-Brannel 160 101 8 206 99 15 Camborne 79 Mabe 143 St. Dominic 183 St. Stephens By Launceston Rural 70 196 16 Camel ford 80 Madron 144 St. Endellion 184 St. Teath 199 210 197 198 17 Card inham 81 Maker-wi th-Rame 145 St. -

Falmouth and Penryn

T N C I R RE O B B L E S 3 O G E N 2 R P R W 92 V G EN O E TIR E E A RO S L AD A D T N S E EN LANEG T E P GRE Penryn RE N L RE E C L E E H I E A U N LA T R RCH H C NE W L M E D E S A AN T O OA IS S R R R T R IN The P EV R N E U R W R Y O H RB E E R O T Islington erformance T EVE LS N ROA T GE TR L TO A S D T D E Penryn W S R Wharf T Centre IA ITHE C Primary V O Rec U M Penryn Rive Academy L To Flushing Trevissome D L M J Ground N RO O G W ub A E CEN E T Court RA CR R M T R O A E A S S ilee Whar S S RK C R E T S A TR W I K E A D ET E C S L PAR I AR N R KE N A r NG PO P C O f UE LT R EN B IS E O R A KO WA S O RD K LS Y T AD D E SA T ST T RA Penryn H REET Kernick Road H Glasney CEN O Penryn W L Q O AY M U L AY W A I HILL Path to Penryn Industrial Estate College D Valley S B H D A S Penryn PA A O T 3 R W R O R L E 2 Harbour RO O E B K IR L K C D I T 9 I A A Glasney 0 0.2 0.4 0.6 0.8 1 E N LT H Kilometres P R E 2 A N E O R K P M Playing Fields E K G BROOK PLACE EN R G U I GUE E AD A RO E T FalmouthG L OD LASNEY PLA O F D L CE L W A AST LM S Little A O E O O O T R P U 0 Miles 0.2 0.4 0.6 Y T C H Y A Eastwood P RO E W E A S Park D T Falmouth E N R O E E W SID N R K O R IEW ' D LI OD E LL S OA T O V V HI K R T W O E R IC D D G How long will it take? KERN L Falmouth O E L O LE AD O A O L Wharves N O A W C 3 mins cycling will take you this far or this far K D To Truro S A A39 VE If you cycle at about 6 miles an hour If you cycle at about 10 miles an hour NU E D A Falmouth E 10 mins walking will take you about this far H Penryn Rive Park and Flushing -

Notes on the Parish of Mylor, Cornwall

C.i i ^v /- NOTES ON THE PARISH OF MYLOR /v\. (crt MVI.OK CII r RCII. -SO UIH I'OKCil AND CROSS O !• ST. MlLoKIS. [NOTES ON THE PARISH OF MYLOR CORNWALL. BY HUGH P. OLIVEY M.R.C.S. Uaunton BARNICOTT &- PEARCE, ATHEN^UM PRESS 1907 BARNICOTT AND PEARCE PRINTERS Preface. T is usual to write something as a preface, and this generally appears to be to make some excuse for having written at all. In a pre- face to Tom Toole and his Friends — a very interesting book published a few years ago, by Mrs. Henry Sandford, in which the poets Coleridge and Wordsworth, together with the Wedgwoods and many other eminent men of that day figure,—the author says, on one occasion, when surrounded by old letters, note books, etc., an old and faithful servant remon- " " strated with her thus : And what for ? she " demanded very emphatically. There's many a hundred dozen books already as nobody ever reads." Her hook certainly justified her efforts, and needed no excuse. But what shall I say of this } What for do 1 launch this little book, which only refers to the parish ot Mylor ^ vi Preface. The great majority of us are convinced that the county of our birth is the best part of Eng- land, and if we are folk country-born, that our parish is the most favoured spot in it. With something of this idea prompting me, I have en- deavoured to look up all available information and documents, and elaborate such by personal recollections and by reference to authorities. -

Licensing-Residential Premises

Cornwall Council Licensing and Management of Houses in Multiple Occupation WARD NAME: Bodmin East Licence Reference HL12_000169 Licence Valid From 05/04/2013 Licence Address 62 St Nicholas StreetBodminCornwallPL31 1AG Renewal Date 05/04/2018 Applicant Name Mr Skea Licence Status Issued Applicant Address 44 St Nicholas StreetBodminCornwallPL31 1AG Licence Type HMO Mandatory Agent Full Name Type of Construction: Semi-Detatched Agent Address Physical Construction: Solid wall Self Contained Unit: Not Self Contained Number of Floors: 3 Number of Rooms Let 10 Permitted Occupancy: Baths and Showers: 3 Cookers: Foodstores: 9 Sinks: Wash Hand Basins: 3 Water Closets: 3 WARD NAME: Bude North And Stratton Licence Reference HL12_000141 Licence Valid From 05/09/2012 Licence Address 4 Maer DownFlexburyBudeCornwallEX23 8NG Renewal Date 05/09/2017 Applicant Name Mr R Bull Licence Status Issued Applicant Address 6 Maer DownFlexburyBudeCornwallEX23 8NG Licence Type HMO Mandatory Agent Full Name Type of Construction: Semi-Detatched Agent Address Physical Construction: Solid wall Self Contained Unit: Not Self Contained Number of Floors: 3 Number of Rooms Let 10 Permitted Occupancy: Baths and Showers: 6 Cookers: Foodstores: Sinks: Wash Hand Basins: 12 Water Closets: 8 16 May 2013 Page 1 of 85 Licence Reference HL12_000140 Licence Valid From 05/09/2012 Licence Address 6 Maer DownFlexburyBudeCornwallEX23 8NG Renewal Date 05/09/2017 Applicant Name Mr R.W. Bull Licence Status Issued Applicant Address MoorhayAshwaterBeaworthyDevonEX21 5DL Licence Type HMO Mandatory Agent Full Name Type of Construction: Semi-Detatched Agent Address Physical Construction: Solid wall Self Contained Unit: Not Self Contained Number of Floors: 3 Number of Rooms Let 8 Permitted Occupancy: Baths and Showers: 8 Cookers: 8 Foodstores: Sinks: Wash Hand Basins: 7 Water Closets: 9 Licence Reference HL12_000140 Licence Valid From 05/09/2012 Licence Address 6 Maer DownFlexburyBudeCornwallEX23 8NG Renewal Date 05/09/2017 Applicant Name Mr R.W. -

Whale Stranding - a Happy Ending

The Port Isaac, Port Gaverne and Trelights newsletter No: 189 • July 1999 • Price 15p Whale stranding - a happy ending n Wednesday May 23rd the Port The Plymouth group On reaching Penberth OIsaac British Divers Marine Life remained on standby Cove we found that Rescue (BDMLR) group took a major in case the rescue went RSPCA officers and step forward when they graduated on into the evening. BDMLR colleagues from from training sessions with plastic, Contact had also been Cweek had rigged up a water filled dolphins and pilot made with BDMLR protective cover over whales to a major, real life whale Directors who were the whale to keep the rescue. ready to move further sunlight off and an equipment down from effective bucket chain ‘Whale ashore’ - the alert was Surrey if required. was in operation to received at 7.30am after a Minke BDMLR vet, James keep the whale’s body whale was sighted by a fisherman Barnett from Bristol, wet and his temperature heading into Penberth Cove near set off to the stranding down. By now news of Lands End. The whale had been site immediately. the stranding was being moving directly towards the shore covered by TV and radio and the fisherman had put his boat First reports received and many spectators across its course in an attempt to indicated that the were arriving together divert it - but to no avail. The whale was 20 feet or with newspaper photo whale became entrapped and then more in length, in graphers and reporters. stranded on large rocks deep into which case additional the Cove on a falling tide. -

Autobiography of Sir George Biddell Airy by George Biddell Airy 1

Autobiography of Sir George Biddell Airy by George Biddell Airy 1 CHAPTER I. CHAPTER II. CHAPTER III. CHAPTER IV. CHAPTER V. CHAPTER VI. CHAPTER VII. CHAPTER VIII. CHAPTER IX. CHAPTER X. CHAPTER I. CHAPTER II. CHAPTER III. CHAPTER IV. CHAPTER V. CHAPTER VI. CHAPTER VII. CHAPTER VIII. CHAPTER IX. CHAPTER X. Autobiography of Sir George Biddell Airy by George Biddell Airy The Project Gutenberg EBook of Autobiography of Sir George Biddell Airy by George Biddell Airy This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg Autobiography of Sir George Biddell Airy by George Biddell Airy 2 License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.net Title: Autobiography of Sir George Biddell Airy Author: George Biddell Airy Release Date: January 9, 2004 [EBook #10655] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK SIR GEORGE AIRY *** Produced by Joseph Myers and PG Distributed Proofreaders AUTOBIOGRAPHY OF SIR GEORGE BIDDELL AIRY, K.C.B., M.A., LL.D., D.C.L., F.R.S., F.R.A.S., HONORARY FELLOW OF TRINITY COLLEGE, CAMBRIDGE, ASTRONOMER ROYAL FROM 1836 TO 1881. EDITED BY WILFRID AIRY, B.A., M.Inst.C.E. 1896 PREFACE. The life of Airy was essentially that of a hard-working, business man, and differed from that of other hard-working people only in the quality and variety of his work. It was not an exciting life, but it was full of interest, and his work brought him into close relations with many scientific men, and with many men high in the State. -

Wind Turbines East Cornwall

Eastern operational turbines Planning ref. no. Description Capacity (KW) Scale Postcode PA12/02907 St Breock Wind Farm, Wadebridge (5 X 2.5MW) 12500 Large PL27 6EX E1/2008/00638 Dell Farm, Delabole (4 X 2.25MW) 9000 Large PL33 9BZ E1/90/2595 Cold Northcott Farm, St Clether (23 x 280kw) 6600 Large PL15 8PR E1/98/1286 Bears Down (9 x 600 kw) (see also Central) 5400 Large PL27 7TA E1/2004/02831 Crimp, Morwenstow (3 x 1.3 MW) 3900 Large EX23 9PB E2/08/00329/FUL Redland Higher Down, Pensilva, Liskeard 1300 Large PL14 5RG E1/2008/01702 Land NNE of Otterham Down Farm, Marshgate, Camelford 800 Large PL32 9SW PA12/05289 Ivleaf Farm, Ivyleaf Hill, Bude 660 Large EX23 9LD PA13/08865 Land east of Dilland Farm, Whitstone 500 Industrial EX22 6TD PA12/11125 Bennacott Farm, Boyton, Launceston 500 Industrial PL15 8NR PA12/02928 Menwenicke Barton, Launceston 500 Industrial PL15 8PF PA12/01671 Storm, Pennygillam Industrial Estate, Launceston 500 Industrial PL15 7ED PA12/12067 Land east of Hurdon Road, Launceston 500 Industrial PL15 9DA PA13/03342 Trethorne Leisure Park, Kennards House 500 Industrial PL15 8QE PA12/09666 Land south of Papillion, South Petherwin 500 Industrial PL15 7EZ PA12/00649 Trevozah Cross, South Petherwin 500 Industrial PL15 9LT PA13/03604 Land north of Treguddick Farm, South Petherwin 500 Industrial PL15 7JN PA13/07962 Land northwest of Bottonett Farm, Trebullett, Launceston 500 Industrial PL15 9QF PA12/09171 Blackaton, Lewannick, Launceston 500 Industrial PL15 7QS PA12/04542 Oak House, Trethawle, Horningtops, Liskeard 500 Industrial -

![CORNWALL.] FAR 952 [POST OFFICE FARMERS Continued](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5174/cornwall-far-952-post-office-farmers-continued-445174.webp)

CORNWALL.] FAR 952 [POST OFFICE FARMERS Continued

[CORNWALL.] FAR 952 [POST OFFICE FARMERS continued. Penna W. Gear, Perranzabuloe, Truro Phillips Jas. Carnhill, Gwinear, Hayle Pearce Voisey, Pillaton, St. Mellion Penny Edward, Butternell, Linkin- PhillipsJas.Raskrow,St.Gluvias,Penryn Pearce W .Calleynough, Helland, Bodmn borne, Callington Phillips J. Bokiddick, Lanivet, Bodmin Pearce W. Helland, Roche, St. Austell Penny Mrs. Luckett, Stoke Clims- Phillips John, Higher Greadow, Lan- Pearce W.Boskell,Treverbyn,St.Austell land, Callington livery, Bodmin Pearce William, Bucklawren, St. Penprage John, Higher Rose vine, Phillips John, Mineral court, St. Martin-by-Looe, Liskeard Gerrans, Grampound Stephens-in-Branwell Pearce Wm. Durfold, Blisland,Bodmin Penrose J. Bojewyan,Pendeen,Penzance Phillips John, N anquidno, St. Just-in- Pearce W. Hobpark, Pelynt, Liskeard Penrose Mrs .•lane, Coombe, Fowey Penwith, Penzance Pearce William, Mesmeer, St. Minver, Penrose J. Goverrow,Gwennap,Redruth Phillips John, Tregurtha, St. Hilary, W adebridge PenroseT .Bags ton, Broadoak ,Lostwi thil M arazion Pearce William,'Praze, St. Erth, Hayle PenroseT. Trevarth, Gwennap,Redruth Phillips John, Trenoweth,l\Iabe,Penryn Pearce William, Roche, St. Austell Percy George, Tutwill, Stoke Clims- Phillips John, Treworval, Constantine, Pearce Wm. Trelask~ Pelynt, Liskeard land, Callington Penryn Pearn John, Pendruffie, Herods Foot, PercyJames, Tutwill, Stoke Climsland, Phillips John, jun. Bosvathick, Con- Liskeard Callington stantine, Penryn Peam John, St. John's, Devonport Percy John, Trehill, Stoke Climsland, Phillips Mrs. Mary, Greadow, Lan- Pearn Robt. Penhale, Duloe, Liskeard Callington livery, Bodmin Pearn S.Penpont, Altemun, Launcestn Percy Thomas, Bittams, Calstock Phillips Mrs. Mary, Penventon,Illogan, Peam T.Trebant, Alternun, Launceston Perkin Mrs. Mary, Haydah, Week St. Redruth PearseE.Exevill,Linkinhorne,Callingtn Mary, Stratton Pl1illips M. -

Environmental Protection Final Draft Report

Environmental Protection Final Draft Report ANNUAL CLASSIFICATION OF RIVER WATER QUALITY 1992: NUMBERS OF SAMPLES EXCEEDING THE QUALITY STANDARD June 1993 FWS/93/012 Author: R J Broome Freshwater Scientist NRA C.V.M. Davies National Rivers Authority Environmental Protection Manager South West R egion ANNUAL CLASSIFICATION OF RIVER WATER QUALITY 1992: NUMBERS OF SAMPLES EXCEEDING TOE QUALITY STANDARD - FWS/93/012 This report shows the number of samples taken and the frequency with which individual determinand values failed to comply with National Water Council river classification standards, at routinely monitored river sites during the 1992 classification period. Compliance was assessed at all sites against the quality criterion for each determinand relevant to the River Water Quality Objective (RQO) of that site. The criterion are shown in Table 1. A dashed line in the schedule indicates no samples failed to comply. This report should be read in conjunction with Water Quality Technical note FWS/93/005, entitled: River Water Quality 1991, Classification by Determinand? where for each site the classification for each individual determinand is given, together with relevant statistics. The results are grouped in catchments for easy reference, commencing with the most south easterly catchments in the region and progressing sequentially around the coast to the most north easterly catchment. ENVIRONMENT AGENCY 110221i i i H i m NATIONAL RIVERS AUTHORITY - 80UTH WEST REGION 1992 RIVER WATER QUALITY CLASSIFICATION NUMBER OF SAMPLES (N) AND NUMBER -

JNCC Coastal Directories Project Team

Coasts and seas of the United Kingdom Region 11 The Western Approaches: Falmouth Bay to Kenfig edited by J.H. Barne, C.F. Robson, S.S. Kaznowska, J.P. Doody, N.C. Davidson & A.L. Buck Joint Nature Conservation Committee Monkstone House, City Road Peterborough PE1 1JY UK ©JNCC 1996 This volume has been produced by the Coastal Directories Project of the JNCC on behalf of the project Steering Group and supported by WWF-UK. JNCC Coastal Directories Project Team Project directors Dr J.P. Doody, Dr N.C. Davidson Project management and co-ordination J.H. Barne, C.F. Robson Editing and publication S.S. Kaznowska, J.C. Brooksbank, A.L. Buck Administration & editorial assistance C.A. Smith, R. Keddie, J. Plaza, S. Palasiuk, N.M. Stevenson The project receives guidance from a Steering Group which has more than 200 members. More detailed information and advice came from the members of the Core Steering Group, which is composed as follows: Dr J.M. Baxter Scottish Natural Heritage R.J. Bleakley Department of the Environment, Northern Ireland R. Bradley The Association of Sea Fisheries Committees of England and Wales Dr J.P. Doody Joint Nature Conservation Committee B. Empson Environment Agency Dr K. Hiscock Joint Nature Conservation Committee C. Gilbert Kent County Council & National Coasts and Estuaries Advisory Group Prof. S.J. Lockwood MAFF Directorate of Fisheries Research C.R. Macduff-Duncan Esso UK (on behalf of the UK Offshore Operators Association) Dr D.J. Murison Scottish Office Agriculture, Environment & Fisheries Department Dr H.J. Prosser Welsh Office Dr J.S.