Rethinking a Reinvigorated Right to Assemble

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Weathering the Legal Academy's Perfect Storm

The Paralegal American Association for Paralegal Education Volume 28, No. 2 WINTER 2013 The Future of Paralegal Programs in Turbulent Times: Weathering the Legal Academy’s Perfect Storm See article on page 21 AAFPE 33RD ANNUAL CONFERENCE Las Vegas/Summerlin See you in Las Vegas/ Summerlin, Nevada! The Paralegal American Association for Paralegal Education The Paralegal Educator is published two times a year by the American Association for Paralegal Education, OF CONTENTS 19 Mantua Road, Mt. Royal, New Jersey 08061. table (856) 423-2829 Fax: (856) 423-3420 E-mail: [email protected] PUBLICATION DATES: Spring/Summer and Fall/Winter Service Learning and Retention in the First Year 5 SUBSCRIPTION RATES: $50 per year; each AAfPE member receives one subscription as part of the membership benefit; additional member subscriptions The Annual Speed Mock Interview Meeting 9 available at the rate of $30 per year. ADVERTISING RATES: (856) 423-2829 The Perils of Unpaid Internships 12 EDITORIAL STAFF: Carolyn Bekhor, JD - Editor-in-Chief Julia Dunlap, Esq. - Chair, Publications Jennifer Gornicki, Esq. - Assistant Editor The Case for Paralegal Clubs 16 Nina Neal, Esq. - Assistant Editor Gene Terry, CAE - Executive Director Writing in Academia 19 PUBLISHER: American Association for Paralegal Education Articles and letters to the editor should be submitted to The Future of Paralegal Programs in Turbulent times: the Chair of the Publications Committee. Weathering the Legal Academy’s Perfect Storm 21 DEADLINES: January 31 and May 31. Articles may be on any paralegal education topic but, on occasion, a Paralegal Educator issue has a central Digital Badges: An Innovative Way to Recognizing Achievements 27 theme or motif, so submissions may be published in any issue at the discretion of the Editor and the Publications Committee. -

Occupy Boise Case

Case 1:12-cv-00076-BLW Document 17 Filed 02/26/12 Page 1 of 16 IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF IDAHO EDWARD WATTERS, DEAN GUNDERSON, STEVEN FARNWORTH, MATTHEW ALEXANDER NEWIRTH, Case No. 1:12-CV-76-BLW individuals, and OCCUPY BOISE, an Idaho unincorporated nonprofit association MEMORANDUM DECISION AND ORDER Plaintiffs, v. C.L. (BUTCH) OTTER, in his official capacity as the Governor of the State of Idaho, TERESA LUNA, in her official capacity of the Director of the Idaho Department of Administration, and COL. G. JERRY RUSSELL, in his official capacity as the Director of the Idaho State Police, Defendants. INTRODUCTION The Court has before it Occupy Boise’s motion for injunctive relief. The Court heard oral argument on the motion on February 24, 2012, and took the motion under advisement. For the reasons explained below, the Court will grant the motion, to the extent it seeks to enjoin the state from removing the symbolic tent city erected by Occupy Boise, but deny the motion, to the extent it seeks to enjoin the occupants from camping, sleeping or storing camping-related personal property at the site. Memorandum Decision & Order - 1 Case 1:12-cv-00076-BLW Document 17 Filed 02/26/12 Page 2 of 16 SUMMARY Occupy Boise’s motion for injunction comes before the Court – as most injunction motions do – on a rushed schedule with expedited briefing. Hasty decisions are rarely wise decisions, and the law recognizes that fact: Preliminary injunctions are issued on a showing of a “likelihood” of success; there is no final resolution of any issue. -

Chapter Is an Example of This Response to the Emerging Lifestyle of the New Middle Class and the Wealthy Capitalists

HOMELESSNESS IN SACRAMENTO: SEARCHING FOR SAFE GROUND Stephen William Watters B.A., California State University, Sacramento, 1978 THESIS Submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in ANTHROPOLOGY at CALIFORNIA STATE UNIVERSITY, SACRAMENTO Spring 2012 © 2012 Stephen William Watters ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii HOMELESSNESS IN SACRAMENTO: SEARCHING FOR SAFE GROUND A Thesis by Stephen William Watters Approved by: __________________________________, Committee Chair Joyce M. Bishop, Ph.D. __________________________________, Second Reader Raghuraman Trichur, Ph.D. ____________________________ Date iii Student: Stephen William Watters I certify that this student has met the requirements for format contained in the University format manual, and that this thesis is suitable for shelving in the Library and credit is to be awarded for the thesis. __________________________, Graduate Coordinator ___________________ Michael Delacorte, Ph.D. Date Department of Anthropology iv Abstract of HOMELESSNESS IN SACRAMENTO, SEARCHING FOR SAFE GROUND by Stephen William Watters The homeless in Sacramento suffer a loss of basic rights, human and civil, and this loss of rights exacerbates the factors that contribute to, and are experienced, as a result of homelessness. Moreover, the emotional, medical, legal and economic problems of the homeless leads to their stigmatization by the general public, as well as by the social service providers and governmental agencies empowered to support them. Once branded as deviant or pathological members of society, the homeless find themselves being treated as second-class citizens. In response to this change of status and in an attempt to gain agency with which to defend themselves, homeless citizens form imagined communities such as my target subject group. -

The Right to Occupyâ•Floccupy Wall Street and the First Amendment

Fordham Urban Law Journal Volume 39 | Number 4 Article 5 February 2016 The Right to Occupy—Occupy Wall Street and the First Amendment Sarah Kunstler Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/ulj Part of the First Amendment Commons, Law and Politics Commons, and the Supreme Court of the United States Commons Recommended Citation Sarah Kunstler, The Right to Occupy—Occupy Wall Street and the First Amendment, 39 Fordham Urb. L.J. 989 (2012). Available at: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/ulj/vol39/iss4/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by FLASH: The orF dham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. It has been accepted for inclusion in Fordham Urban Law Journal by an authorized editor of FLASH: The orF dham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. For more information, please contact [email protected]. KUNSTLER_CHRISTENSEN 7/11/2012 9:25 AM THE RIGHT TO OCCUPY—OCCUPY WALL STREET AND THE FIRST AMENDMENT ∗ Sarah Kunstler Eternal vigilance is the price of liberty—power is ever stealing from the many to the few.1 Wendell Phillips, January 28, 1852 Introduction ............................................................................................. 989 I. Symbolic Speech ............................................................................... 993 II. Symbolic Sleeping and the Courts ................................................. 999 III. The Landscape of Symbolic Sleep Protection After Clark v. CCNV .......................................................................................... 1007 IV. The Occupy Movement in the Courts ....................................... 1012 Conclusion .............................................................................................. 1018 INTRODUCTION The Occupy movement, starting with Occupy Wall Street in Zuccotti Park in New York City, captured the public imagination and spread across the country with a force and rapidity that no one could have predicted. -

Table of Contents Ch

Table of Contents Ch. 27 leads large contingent to SOA protests ........................................................................................................................... 2 Melting weapons of war into bells for peace ................................................................................................................................ 2 Time for apologies ....................................................................................................................................................................... 3 “A bayonet is a weapon with a worker at each end.” ......................................................................................................... 3 War depravation has never caused a single case of post traumatic stress. ...................................................................... 5 Iran in the Crosshairs: Stop the March to War .......................................................................................................................... 6 George McGovern, a true candidate for peace ......................................................................................................................... 7 Iran, from previous page ............................................................................................................................................................. 7 Occupy Homes and Occupy Minneapolis update ....................................................................................................................... 8 Strib prints -

Zerohack Zer0pwn Youranonnews Yevgeniy Anikin Yes Men

Zerohack Zer0Pwn YourAnonNews Yevgeniy Anikin Yes Men YamaTough Xtreme x-Leader xenu xen0nymous www.oem.com.mx www.nytimes.com/pages/world/asia/index.html www.informador.com.mx www.futuregov.asia www.cronica.com.mx www.asiapacificsecuritymagazine.com Worm Wolfy Withdrawal* WillyFoReal Wikileaks IRC 88.80.16.13/9999 IRC Channel WikiLeaks WiiSpellWhy whitekidney Wells Fargo weed WallRoad w0rmware Vulnerability Vladislav Khorokhorin Visa Inc. Virus Virgin Islands "Viewpointe Archive Services, LLC" Versability Verizon Venezuela Vegas Vatican City USB US Trust US Bankcorp Uruguay Uran0n unusedcrayon United Kingdom UnicormCr3w unfittoprint unelected.org UndisclosedAnon Ukraine UGNazi ua_musti_1905 U.S. Bankcorp TYLER Turkey trosec113 Trojan Horse Trojan Trivette TriCk Tribalzer0 Transnistria transaction Traitor traffic court Tradecraft Trade Secrets "Total System Services, Inc." Topiary Top Secret Tom Stracener TibitXimer Thumb Drive Thomson Reuters TheWikiBoat thepeoplescause the_infecti0n The Unknowns The UnderTaker The Syrian electronic army The Jokerhack Thailand ThaCosmo th3j35t3r testeux1 TEST Telecomix TehWongZ Teddy Bigglesworth TeaMp0isoN TeamHav0k Team Ghost Shell Team Digi7al tdl4 taxes TARP tango down Tampa Tammy Shapiro Taiwan Tabu T0x1c t0wN T.A.R.P. Syrian Electronic Army syndiv Symantec Corporation Switzerland Swingers Club SWIFT Sweden Swan SwaggSec Swagg Security "SunGard Data Systems, Inc." Stuxnet Stringer Streamroller Stole* Sterlok SteelAnne st0rm SQLi Spyware Spying Spydevilz Spy Camera Sposed Spook Spoofing Splendide -

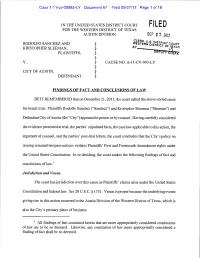

Sanchez and Western District Court § District 0 Kristopher Sleeman, § Plaintiffs, § § V

Case 1:11-cv-00993-LY Document 67 Filed 09/27/12 Page 1 of 18 IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FILED FOR THE WESTERN DISTRICT OF TEXAS AUSTIN DIVISION SEP 2 7 2012 CLERK U.S. RODOLFO SANCHEZ AND WESTERN DISTRICT COURT § DISTRICT 0 KRISTOPHER SLEEMAN, § PLAINTIFFS, § § V. § CAUSE NO. A-1 1-CV-993-LY § CITY OF AUSTIN, § DEFENDANT. § FINDINGS OF FACT AND CONCLUSIONS OF LAW BE IT REMEMBERED that on December 21, 2011, the court called the above-styled cause for bench trial. Plaintiffs Rodolfo Sanchez ("Sanchez") and Kristopher Sleeman ("Sleeman") and Defendant City of Austin (the "City") appeared in person or by counsel. Having carefully considered the evidence presented at trial, the parties' stipulated facts, the case law applicable to this action, the argument of counsel, and the parties' post-trial letters, the court concludes that the City's policy on issuing criminal-trespass notices violates Plaintiffs' First and Fourteenth Amendment rights under the United States Constitution. In so deciding, the court makes the following findings of fact and conclusions of law.1 Jurisdiction and Venue The court has jurisdiction over this cause as Plaintiffs' claims arise under the United States Constitution and federal law. See 28 U.S.C. § 1331. Venue is proper because the underlying events giving rise to this action occurred in the Austin Division of the Western District of Texas, which is also the City's primary place of business. All findings of fact contained herein that are more appropriately considered conclusions of law are to be so deemed. Likewise, any conclusion of law more appropriately considered a finding of fact shall be so deemed. -

RETHINKING ASSEMBLY ORDINANCES: THREE CONSIDERATIONS CITIES SHOULD MAKE to AVOID ANOTHER FERGUSON OR BALTIMORE-TYPE RIOT Christopher W

Ohio Northern University Law Review Volume 44 | Issue 1 Article 1 RETHINKING ASSEMBLY ORDINANCES: THREE CONSIDERATIONS CITIES SHOULD MAKE TO AVOID ANOTHER FERGUSON OR BALTIMORE-TYPE RIOT Christopher W. Bloomer Indiana University Robert H. McKinney School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.onu.edu/onu_law_review Part of the Civil Law Commons, and the Law and Race Commons Recommended Citation Bloomer, Christopher W. () "RETHINKING ASSEMBLY ORDINANCES: THREE CONSIDERATIONS CITIES SHOULD MAKE TO AVOID ANOTHER FERGUSON OR BALTIMORE-TYPE RIOT," Ohio Northern University Law Review: Vol. 44 : Iss. 1 , Article 1. Available at: https://digitalcommons.onu.edu/onu_law_review/vol44/iss1/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@ONU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Ohio Northern University Law Review by an authorized editor of DigitalCommons@ONU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Bloomer: RETHINKING ASSEMBLY ORDINANCES: THREE CONSIDERATIONS CITIES SHOUL Ohio Northern University Law Review Lead Articles Rethinking Assembly Ordinances: Three Considerations Cities Should Make To Avoid Another Ferguson Or Baltimore-Type Riot CHRISTOPHER W. BLOOMER* INTRODUCTION It is never fun footing someone else’s bill. However, cost-covering and redistribution happens with practically all illegal and destructive riots and protests that occur in the United States.1 For example, repairs from the lawless demonstrations siphoned off more than $5.7 million of local funds during the 2014 Ferguson, Missouri Riots.2 How about the 2015 Baltimore riots? The riots cost Baltimore more than $20 million, and even though the mayor refused to stop the rioting, the city requested payment assistance from the federal government to cover the tab.3 Not typically known as a site of unrest, North Dakota spent more than $38 million policing the 2016 Keystone Pipeline protests, with the Federal Emergency Management * J.D., cum laude Indiana University Robert H. -

Occupy Anniversary

Year II tidalOccupy Theory, Occupy Strategy n Sept 2012 2 tidal 3 Communiqué #3 19 On the Transformative Potential of Race and Difference in Post-Left Movements 5 What is to be Done? pamEla bridGEwatEr Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak 20 On Transparency, Leadership, and Participation 9 The Revolution Will Not Have a Bottom Line Suzahn Ebrahimian 21 Where Are We? Who Are We? Occupy, Space, and Community 10 “Strike Debt!” nina nEhta folkS from StrikE dEbt 21 Letter to the Well-Meaning 1% 12 Stop and Frisk and Other Racist thE 99% Capitalist Bullshit joSé martín 22 Mutual Aid in the Face of the Storm ChriStophEr kEy 14 The Power of the Powerless jErEmy brEChEr 24 Beyond Climate, Beyond Capitalism vanya S, talib aGapE fuEGovErdE, v. C. vitalE 16 S17: Occupy Wall Street Anniversary 26 After the Jubilee david GraEbEr Notes 29 On Debt and Privilege 18 The War on Dissent, the War on Communities wintEr jEn wallEr and tom hintzE 30 On Living 18 On Political Repression, Jail Support, nazim hikmEt and Radical Care mutant lEGal workinG Group 31 First Communiqué: Invisible Army Editorial Design Thanks Find Us vanya s. zak greene + nicholas mirzoeff r. black occupytheory.org amin husain nona hildebrand marina berio bradley treadway [email protected] yates mckee jed brandt diedra donohue laura gottesdiener astra taylor austin guest TidalOccupyTheory @occupytheory Tidal is distributed for free. Our work for Tidal is free. Our one expense is printing costs. Please support the printing of Tidal at occupytheory.org/donate 3 Communiqué #3 he world ultimately comes down to dreams and their Sure, there’s the awkward issue that grand dreams cannot realization. -

1 United States District Court for the District Of

Case 1:13-cv-00595-RMC Document 18 Filed 03/12/14 Page 1 of 31 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA ) RYAN NOAH SHAPIRO, ) ) Plaintiff, ) ) v. ) Civil Action No. 13-595 (RMC) ) U.S. DEPARTMENT OF JUSTICE, ) ) Defendant. ) ) OPINION Ryan Noah Shapiro sues the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) under the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA), 5 U.S.C. § 552, and the Privacy Act (PA), 5 U.S.C. § 552a, to compel the release of records concerning “Occupy Houston,” an offshoot of the protest movement and New York City encampment known as “Occupy Wall Street.” Mr. Shapiro seeks FBI records regarding Occupy Houston generally and an alleged plot by unidentified actors to assassinate the leaders of Occupy Houston. FBI has moved to dismiss or for summary judgment.1 The Motion will be granted in part and denied in part. I. FACTS Ryan Noah Shapiro is a doctoral candidate in the Department of Science, Technology, and Society at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Compl. [Dkt. 1] ¶ 2. In early 2013, Mr. Shapiro sent three FOIA/PA requests to FBI for records concerning Occupy Houston, a group of protesters in Houston, Texas, affiliated with the Occupy Wall Street protest movement that began in New York City on September 17, 2011. Id. ¶¶ 8-13. Mr. Shapiro 1 FBI is a component of the Department of Justice (DOJ). While DOJ is the proper defendant in the instant litigation, the only records at issue here are FBI records. For ease of reference, this Opinion refers to FBI as Defendant. 1 Case 1:13-cv-00595-RMC Document 18 Filed 03/12/14 Page 2 of 31 explained that his “research and analytical expertise . -

Responses from Cities RE: Occupy Groups

Responses from Cities RE: Occupy Groups 1. Have you had any interaction with an 2. If so, is it necessary for them to acquire 3. If yes, has the group followed 4. Have you had to restrict their use of Occupy Wall Street-like group, also permits or to provide documentation of through with securing the the park and if so, how were the City known as 99%, in your city? another type to be in the park? documentation? restrictions enforced? Other Comments Yes, by City of Austin Parks and Recreation The group did receive information Yes. There have been permitting Department rules, permits are required for from city entities through a joint The City has not had to restrict usage of discussions with them as soon as our local organized events, or for any element that information sharing meeting with any park during this 3 week timeframe public safety officials received intelligence would regularly require a permit by law identified leaders or key person in the beyond ensuring messaging related to as to a potential (amplified sound, camping, occupying a park movement. No permit request was existing park rules, and proactive Austin, TX assembly/occupation/event. beyond curfew). received to occupy a park. enforcement where minimally needed. We are enforcing City Park rules in parks They have been compliant with Cities as we would in all cases. However, since request (Police have been extremely the Plaza is not designated as a Park it is Yes, Park property first day and Plaza They decided after first day to use a plaza in helpful in enforcing our Camping being treated as a Public Forum. -

On Social Interaction Metrics

ON SOCIAL INTERACTION METRICS SOCIAL INTERACTION ON ABSTRACT The use of online social networks poses interes- necessarily have to be connected. Methods using ting big data challenges. With limited resources it the same data to identify and cluster different opi- is important to evaluate and prioritize interesting nions in online communities have been developed ON SOCIAL INTERACTION METRICS data. This thesis addresses the following aspects of and evaluated. SOCIAL NETWORK CRAWLING BASED ON social network analysis: efficient data collection, The privacy of the content produced and the social interaction evaluation and user privacy con- end-users’ private information provided in social INTERESTINGNESS cerns. networks is important to protect. Users should be It is possible to collect data from most online aware of the privacy-related consequence of pos- social networks via their open APIs. However, a ting in online social networks in terms of privacy. systematic and efficient collection of online social Therefore, mitigating privacy risks contributes to a networks data is still challenging. Results in this secure environment and methods to protect user thesis suggest that the collection time can be privacy are presented. reduced to 48% by prioritizing the collection of The proposed tool has, over the period of 20 posts. months, collected 38 millionposts from public pa- Fredrik Erlandsson Evaluation of social interactions requires data ges on Facebook which include, 4 billion likes and that covers all the interactions in a given domain. 340 million comments from 280 million users. The This has previously been difficult to do. In this the- data collection is, to the best of our knowledge, sis we propose a tool that is capable of extracting the largest research dataset of social interactions all social interactions from Facebook.