PETITIONERS V

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Congressional Record United States Th of America PROCEEDINGS and DEBATES of the 112 CONGRESS, SECOND SESSION

E PL UR UM IB N U U S Congressional Record United States th of America PROCEEDINGS AND DEBATES OF THE 112 CONGRESS, SECOND SESSION Vol. 158 WASHINGTON, WEDNESDAY, MAY 23, 2012 No. 75 House of Representatives The House was not in session today. Its next meeting will be held on Friday, May 25, 2012, at 10 a.m. Senate WEDNESDAY, MAY 23, 2012 The Senate met at 9:30 a.m. and was to the Senate from the President pro SCHEDULE called to order by the Honorable tempore (Mr. INOUYE). Mr. REID. Madam President, we are KIRSTEN E. GILLIBRAND, a Senator from The assistant legislative clerk read now on the motion to proceed to the the State of New York. the following letter: FDA user fees bill. Republicans control U.S. SENATE, the first half hour, the majority the PRAYER PRESIDENT PRO TEMPORE, second half hour. We are working on an The Chaplain, Dr. Barry C. Black, of- Washington, DC, May 23, 2012. agreement to consider amendments to fered the following prayer: To the Senate: the FDA bill. We are close to being able Under the provisions of rule I, paragraph 3, Eternal God, You have made all to finalize that. We hope to get an of the Standing Rules of the Senate, I hereby agreement and avoid filing cloture on things well. Thank You for the light of appoint the Honorable KIRSTEN E. GILLI- the bill. day and the dark of night. Thank You BRAND, a Senator from the State of New for the glory of the sunlight, for the York, to perform the duties of the Chair. -

Contractor's SUV Bombed

Eagles Weekend NEGLECTED HORSES UPDATE basketball entertainment Group still in need of help ......................................Page 1 .............Page 6 ..............Page 3 INSIDE Mendocino County’s World briefly The Ukiah local newspaper ..........Page 2 Tomorrow: Partly sunny 7 58551 69301 0 THURSDAY Feb. 2, 2006 50 cents tax included DAILY JOURNAL ukiahdailyjournal.com 16 pages, Volume 147 Number 299 email: [email protected] Contractor’s SUV bombed MC dean Second bomb that disagrees failed to explode detonated at Masonite with study By BEN BROWN Says local graduates The Daily Journal Ukiah Valley firefighters and have higher math Mendocino County sheriff’s skills than AIR found deputies responded to a vehicle fire at the home of local contractor The Daily Journal Brandon Hidalgo on Canyon Drive A recent study that implies many early Wednesday, and discovered college students only possess basic two incendiary devices, one of literacy skills “does not gibe” for which had failed to explode. Mendocino College Dean of Police and firefighters were sum- Instruction Meridith Randall. moned by a 911 call at 3:30 a.m. “Twenty percent of U.S. college After the fire was extinguished, a students completing four-year search of the vehicle -- a 2004 degrees -- and 30 percent of students Chevrolet Suburban -- revealed the two devices, which were under the See COLLEGE, Page 15 car. Hidalgo said the vehicle was totaled but that nothing else was damaged. Parked next to the Escaped Suburban was the trailer where Hidalgo keeps his work tools. “We lucked out,” he said. Hidalgo said he was notified of inmate the fire by his neighbor, who works as a butcher in Willits. -

United States Court of Appeals for the Eighth Circuit ______

United States Court of Appeals For the Eighth Circuit ___________________________ No. 12-3524 ___________________________ Bryan St. Patrick Gallimore lllllllllllllllllllllPetitioner v. Eric H. Holder, Jr., Attorney General of the United States lllllllllllllllllllllRespondent ____________ Petition for Review of an Order of the Board of Immigration Appeals ____________ Submitted: May 15, 2013 Filed: May 22, 2013 ____________ Before RILEY, Chief Judge, MELLOY and SHEPHERD, Circuit Judges. ____________ RILEY, Chief Judge. The Department of Homeland Security (DHS) ordered Bryan St. Patrick Gallimore, a native and citizen of Jamaica, removed as an alien convicted of an aggravated felony. The immigration judge (IJ) denied Gallimore’s petition to defer removal pursuant to the Convention Against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CAT), Art. 3, Dec. 10, 1984, S. Treaty Doc. No. Appellate Case: 12-3524 Page: 1 Date Filed: 05/22/2013 Entry ID: 4037987 100-20, at 20, and ordered Gallimore removed. See 8 C.F.R. § 1208.18. The Board of Immigration Appeals (BIA) affirmed and dismissed Gallimore’s appeal. Gallimore petitions for review of the BIA’s decision, and we dismiss Gallimore’s petition. I. BACKGROUND In 2008, Gallimore was sentenced to a term of imprisonment not to exceed ten years for burglary in the second degree, in violation of Iowa Code sections 713.1 and 713.5. Gallimore’s sentence was to run concurrently with his state sentences for stalking and harassment. On July 1, 2011, DHS ordered Gallimore removed under 8 U.S.C. § 1227(a)(2)(A)(iii) as an “alien who is convicted of an aggravated felony at any time after admission.” An aggravated felony includes a “burglary offense for which the term of imprisonment [is] at least one year.” Id. -

Texas Rules of Appellate Procedure

TEXAS RULES OF APPELLATE PROCEDURE Table of Contents SECTION ONE. (c) Where to File. GENERAL PROVISIONS (d) Order of the Court. Rule 1. Scope of Rules; Local Rules of Courts of Rule 5. Fees in Civil Cases Appeals Rule 6. Representation by Counsel 1.1. Scope. 6.1. Lead Counsel 1.2. Local Rules (a) For Appellant. (a) Promulgation. (b) For a Party Other Than Appellant. (b) Copies. (c) How to Designate. (c) Party's Noncompliance. 6.2. Appearance of Other Attorneys Rule 2. Suspension of Rules 6.3. To Whom Communications Sent Rule 3. Definitions; Uniform Terminology 6.4. Nonrepresentation Notice 3.1. Definitions (a) In General. (b) Appointed Counsel. 3.2. Uniform Terminology in Criminal Cases 6.5. Withdrawal (a) Contents of Motion. Rule 4. Time and Notice Provisions (b) Delivery to Party. (c) If Motion Granted. 4.1. Computing Time (d) Exception for Substitution of (a) In General. Counsel. (b) Clerk's Office Closed or Inaccessible. 6.6. Agreements of Parties or Counsel 4.2. No Notice of Trial Court’s Judgment Rule 7. Substituting Parties in Civil Case (a) Additional Time to File Documents. 7.1. Parties Who Are Not Public Officers (1) In general. (a) Death of a Party. (2) Exception for restricted appeal. (1) Civil Cases. (b) Procedure to Gain Additional Time. (2) Criminal Cases. (c) The Court’s Order. (b) Substitution for Other Reasons. 4.3. Periods Affected by Modified 7.2. Public Officers Judgment in Civil Case (a) Automatic Substitution of Officer. (a) During Plenary-Power Period. (b) Abatement. (b) After Plenary Power Expires. -

Federal Register/Vol. 79, No. 205/Thursday, October 23, 2014

63416 Federal Register / Vol. 79, No. 205 / Thursday, October 23, 2014 / Notices which counselors are aware of and Crisis counselors at eight new caller’s consent, (9) whether imminent being guided by the Lifeline’s imminent participating centers will record risk was reduced enough such that risk guidelines; counselors’ definitions information discussed with imminent active rescue was not needed, (10) of imminent risk; the rates of active risk callers on the Imminent Risk Form- interventions for third party callers rescue of imminent risk callers; types of Revised, which does not require direct calling about a person at imminent risk, rescue (voluntary or involuntary); data collection from callers. As with (11) whether supervisory consultation barriers to intervention; circumstances previously approved evaluations, callers occurred during or after the call, (12) in which active rescue is initiated, will maintain anonymity. Counselors barriers to getting needed help to the including the caller’s agreement to will be asked to complete the form for person at imminent risk, (13) steps receive the intervention, profile of 100% of imminent risk callers to the taken to confirm whether emergency imminent risk callers; and the types of eight centers participating in the contact was made with person at risk, interventions counselors used with evaluation. This form requests (14) outcome of attempts to rescue them. information in 15 content areas, each person at risk, and (15) outcome of Clearance is being requested for one with multiple sub-items and response attempts to follow-up on the case. The activity to assess the knowledge, options. Response options include revised form reduces and streamlines actions, and practices of counselors to open-ended, yes/no, Likert-type ratings, responses options for intervention aid callers who are determined to be at and multiple choice/check all that questions. -

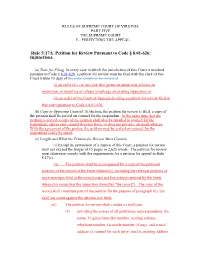

Rule 5:17A. Petition for Review Pursuant to Code § 8.01-626; Injunctions

RULES OF SUPREME COURT OF VIRGINIA PART FIVE THE SUPREME COURT E. PERFECTING THE APPEAL Rule 5:17A. Petition for Review Pursuant to Code § 8.01-626; Injunctions. (a) Time for Filing. In every case in which the jurisdiction of this Court is invoked pursuant to Code § 8.01-626, a petition for review must be filed with the clerk of this Court within 15 days of the order sought to be reviewed. (i) an order of a circuit court that grants an injunction, refuses an injunction, or dissolves or refuses to enlarge an existing injunction; or (ii) an order of the Court of Appeals deciding a petition for review filed in that court pursuant to Code § 8.01-626. (b) Copy to Opposing Counsel. At the time the petition for review is filed, a copy of the petition shall be served on counsel for the respondent. At the same time that the petition is served, a copy of the petition shall also be emailed to counsel for the respondent, unless said counsel does not have, or does not provide, an email address. With the agreement of the parties, the petition may be served on counsel for the respondent solely by email. (c) Length and What the Petition for Review Must Contain. (i) Except by permission of a Justice of this Court, a petition for review shall not exceed the longer of 15 pages or 2,625 words. The petition for review must otherwise comply with the requirements for a petition for appeal in Rule 5:17(c). (ii) The petition shall be accompanied by a copy of the pertinent portions of the record of the lower tribunal(s), including the relevant portions of any transcripts filed in the circuit court and the order(s) entered by the lower tribunal(s) respecting the injunction (hereafter "the record"). -

Appellate Practice Handbook

KANSAS APPELLATE PRACTICE HANDBOOK 6TH EDITION KANSAS JUDICIAL COUNCIL Subscription Information The Kansas Appellate Practice Handbook is updated on a periodic basis with supplements to reflect important changes in both statutory law and case law. Your purchase of this publication automatically records your subscription for the update service. If you do not wish to receive the supplements, you must inform the Judicial Council. You may contact the Judicial Council by e-mail at [email protected], by telephone at (785) 296-2498 or by mail at: Kansas Judicial Council 301 SW 10th, Ste. 140 Topeka, KS 66612 © 2019 KANSAS JUDICIAL COUNCIL ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii PREFACE TO THE SIXTH EDITION This is the first edition of the Handbook since the advent of electronic filing of appellate cases. All prior editions, while containing some useful suggestions, are obsolete. With clear marching orders from our Supreme Court, all appellate attorneys must enroll and monitor their cases. Paper filing is now relegated to litigants that are unrepresented. Prompted by these massive changes we have consolidated some chapters and subjects and created new sections for electronic filing. But there is more to an appeal than just getting in the door. Scheduling, briefing, and pre- and post-opinion motion practice are dealt with. We sincerely hope that this work will be helpful to all who practice in this important area of the law. It is an attempt to open up the mysteries of electronic filing of appellate cases in Kansas. I must shout from the rooftops my praise for Christy Molzen with the Kansas Judicial Council, who has done all of the heavy lifting in putting this handbook together. -

YELP, INC., Appellant

823 v~9\~s ·u SUPREME COURT COPXiPREMECOUR1 FILE,D Case No. S--- JUL 18 2016 IN THE SUPREME COURT Frank A. McGuire Clerk OF THE STATE OF CALIFORNIA Deputy DAWN HASSELL, et al. Plaintiffs and Respondents, vs. AVA BIRD, Defendant, YELP INC., Appellant. After a Decision by the Court of Appeal First Appellate District, Division Four, Case No. Al43233 Superior Court of the County of San Francisco Case No. CGC-13-530525, The Honorable Ernest H. Goldsmith PETITION FOR REVIEW DAVIS WRIGHT TREMAINE LLP THOMAS R. BURKE [email protected] (SB# 141930) *ROCHELLE [email protected] (SB# 197790) 505 Montgomery Street, Suite 800, San Francisco, CA 94111-6533 Tel.: (415) 276-6500 Fax: (415) 276-6599 YELP INC. AARON SCHUR [email protected] (SB# 229566) 140 New Montgomery Street, San Francisco, California 94105 Tel: (415) 908-3801 Attorneys for Non-Party Appellant YELP INC. Case No. S--- IN THE SUPREME COURT OF THE STATE OF CALIFORNIA DAWN HASSELL, et al. Plaintiffs and Respondents, vs. AVA BIRD, Defendant, YELP, INC., Appellant. After a Decision by the Court of Appeal First Appellate District, Division Four, Case No. Al43233 Superior Court of the County of San Francisco Case No. CGC-13-530525, The Honorable Ernest H. Goldsmith PETITION FOR REVIEW DAVIS WRIGHT TREMAINE LLP THOMAS [email protected] (SB# 141930) *ROCHELLE [email protected] (SB# 197790) 505 Montgomery Street, Suite 800, San Francisco, CA 94111-6533 Tel.: (415) 276-6500 Fax: (415) 276-6599 YELP INC. AARON SCHUR [email protected] (SB# 229566) 140 New Montgomery Street, San Francisco, California 94105 Tel: (415) 908-3801 Attorneys for Non-Party Appellant YELP INC. -

SUPREME COURT of the UNITED STATES NOV 292018 I OFFICE of the CLERK Ljflp Fl(Th in Re EFRAIN CAMPOS, Petitioner, Vs

Ilk • 1 2ORIGINAL CASE NO: 3 - as IN THE T FILED SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES NOV 292018 I OFFICE OF THE CLERK LjfLP fl(Th In re EFRAIN CAMPOS, Petitioner, vs. SUE NOVAK, Warden [Columbia Correctional Institution), Respondent. ON PETITION FOR WRIT OF HABEAS CORPUS TO WISCONSIN STATE SUPREME COURT PETITION FOR WRIT OF HABEAS CORPUS NR. EFRAIN CAMPOS [#374541-A] Columbia Correctional Institution Post Office Box 900 I CCI-Unit-#9. Portage; Wisconsin. 53901-0900 QUESTION(S) PRESENTED Was Petitioner Efrain Campos Denied A Fundamentally Fair Guilty Plea Procedural Execution, By The With Holding Of Information By The Assistant District Attorney Regarding The State Sophistical Elimination Of Discretionary Parole Actuality Via Its "Violent Offender Incarceration Program--Tier #1" Agreement With The Federal Government? Was The Discovery Of The Hidden "Violent Offender Incar- ceration Program--Tier #1" Agreement Between The State Of Wisconsin And The Federal Government, A Relevant "Factor" Sufficient To War- rant An Adjustment Of Defendant Efrain Campos Sentence Structure To Meet The" ,,Sentencing Courts' Implied Promise That The Sentence It Imposed Would Provide This First Time Offender With A "Meaningful" Chance For Discretionary Parole Consideration In Approximately 17 to 20 Years? Was The Hidden Actions Of The State Of Wisconsin Govern- ments, In Its Participation In The "Violent Offender Incarceration Program--Tier #1," A Violation Of A Defendants' Right To Intelligently And Knowingly Eater Into A Plea Agreement In Which The State Selling Promise Was The "Genuine Possibility" Of Discretionary Parole Release Consideration In About 17 To 20 Years? What Is the Available Procedural Review Process For Dis- covery That The Plea Process And Sentencing Receipt Thereof, Were The Product Of Fraud In The Information Relied Upon. -

Nationwide Cyber Security Review (NCSR) Assessment

43696 Federal Register / Vol. 76, No. 140 / Thursday, July 21, 2011 / Notices (11) if supervisory consultation contact was NOT made with person at counselors over the two-year data occurred, (12) barriers to getting needed risk. The form will take approximately collection period. help to the person at imminent risk, (13) 15 minutes to complete and may be The estimated response burden to steps taken to confirm emergency completed by the counselor during or collect this information is annualized contact was made with person at risk, after the call. It is expected that a total over the requested two-year clearance and (14) steps taken when emergency of 1,440 forms will be completed by 360 period and is presented below: TOTAL AND ANNUALIZED AVERAGES—RESPONDENTS, RESPONSES AND HOURS Number of Responses/ Total Hours per Total hour Instrument respondents respondent responses response burden National Suicide Prevention Lifeline—Imminent Risk Form 360 2 720 .25 180 Send comments to Summer King, This process is conducted in accordance FOR FURTHER INFORMATION CONTACT: SAMHSA Reports Clearance Officer, with 5 CFR 1320.10. Michael Leking, DHS/NPPD/CS&C/ Room 8–1099, One Choke Cherry Road, ADDRESSES: Interested persons are NCSD/CSEP, [email protected]. Rockville, MD 20857 AND e-mail her a invited to submit written comments on SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION: Per House copy at [email protected]. the proposed information collection to Report 111–298 and Senate Report 111– Written comments should be received the Office of Information and Regulatory 31, Department of Homeland Security within 60 days of this notice. -

In the United States District Court for the Western District of Pennsylvania

Case 2:16-cv-01250-LPL Document 23 Filed 01/22/18 Page 1 of 8 IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE WESTERN DISTRICT OF PENNSYLVANIA ALONZO LAMAR JOHNSON, ) ) Civil Action No. 16 - 1250 Petitioner, ) ) v. ) ) Magistrate Judge Lisa Pupo Lenihan BARBARA RICKARD and THE ) ATTORNEY GENERAL OF THE ) STATE OF PENNSYLVANIA, ) ) Respondents. ) MEMORANDUM OPINION Alonzo Lamar Johnson (“Petitioner”) has filed a Petition for Writ of Habeas Corpus pursuant to 28 U.S.C. § 2254 (“Petition”) challenging his judgment of sentence of three (3) to six (6) years’ imprisonment entered by the Court of Common Pleas of Allegheny County, Pennsylvania at CC No. 200804649 on July 13, 2010.1 (ECF No. 6.) Petitioner’s judgment of sentence stems from his conviction for escape, possession with the intent to deliver a controlled substance and possession of a controlled substance. (Resp’t Ex. 1, ECF No. 13-1, pp.1-17; Resp’t Ex. 1, ECF No. 13-1, pp.18-21.) For the following reasons the Petition will be dismissed for lack of jurisdiction. A. Relevant Procedural History After he was sentenced, Petitioner filed a Notice of Appeal in the Superior Court of Pennsylvania, which was docketed at No. 1939 WDA 2010. (Resp’t Ex. 9, ECF No. 13-2, pp.1- 1 The docket sheet for Petitioner’s criminal case is a matter of public record and available for public view at https://ujsportal.pacourts.us/ 1 Case 2:16-cv-01250-LPL Document 23 Filed 01/22/18 Page 2 of 8 4.) In a Memorandum filed on April 13, 2012, the Superior Court affirmed Petitioner’s judgment of sentence. -

United States Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit ______

Case: 08-3836 Document: 00617943611 Filed: 12/18/2009 Page: 1 RECOMMENDED FOR FULL-TEXT PUBLICATION Pursuant to Sixth Circuit Rule 206 File Name: 09a0430p.06 UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE SIXTH CIRCUIT _________________ KWASI ACQUAAH, X Petitioner, - - - No. 08-3836 v. - > , ERIC H. HOLDER, JR., Attorney General, - Respondent. - N On Petition for Review from a Final Order of the Board of Immigration Appeals. No. A79 669 319. Submitted: December 3, 2009 Decided and Filed: December 18, 2009 Before: SILER, GILMAN, and ROGERS, Circuit Judges. _________________ COUNSEL ON BRIEF: Ilissa M. Gould, UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF JUSTICE, Washington, D.C., for Respondent. Kwasi Acquaah, Oakdale, Louisiana, pro se. _________________ OPINION _________________ RONALD LEE GILMAN, Circuit Judge. Kwasi Acquaah, a native and citizen of Ghana, appeals a decision by the Board of Immigration Appeals (BIA) denying two separate motions to reopen his removal proceedings. An Immigration Judge (IJ) ordered Acquaah removed in absentia when Acquaah failed to appear at his master-calendar hearing due to a mistaken belief as to the proper hearing date. For the reasons set forth below, we DENY Acquaah’s petition for review. 1 Case: 08-3836 Document: 00617943611 Filed: 12/18/2009 Page: 2 No. 08-3836 Acquaah v. Holder Page 2 I. BACKGROUND A. Factual background Acquaah was admitted to the United States in January 2000 as a nonimmigrant student to attend the University of Arkansas. When Acquaah stopped attending school the following year, the Immigration and Naturalization Service issued him a Notice to Appear. The Notice informed Acquaah that he was subject to removal from the country for failing to comply with the conditions of his nonimmigrant status.