Porter's Value Chain

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ebola II African Airlines.Pdf

SENIOR ADVISORY TEAM: FRONTIER MARKETS SPECIALISTS Lord Paul Boateng Fmr. UK Chief Secretary to the Treasury OCTOBER 1, 2014 & High Commissioner to South Africa (*International Legal Counsel to DaMina Advisors LLP) DaMina Advisors Note: Africa’s struggling airlines face possible insolvencies if the Dr. Babacar Ndiaye US and EU enact strict travel restrictions to Ebola affected West African nations. Fmr. President of the African Development Bank Africa’s financially struggling airline industry which supports over 7 million jobs and contributes Dr. Ablasse Ouedraogo $80bn in GDP may witness several financial insolvencies if the US and EU impose strict travel Fmr. Foreign Minister of Burkina Faso restrictions to West Africa. With the first US confirmed case of Ebola diagnosed in Texas, and H.E. Kabine Komara growing public pressure on the Obama administration to restrict US airline travel to West Fmr. Guinean Prime Minister Africa, the financial viability of a number of already struggling domestic African airline carriers Hon. Victor Kasongo Shomary may be under threat. The financial viability of several domestic African airlines such as: Asky Fmr. DRCongo Deputy Minister of Mines Airlines (Togo), Senegal Airlines (Senegal), CAA (DR Congo), Camair-co (Cameroon), Afric H.E. Isaiah Chabala Fmr. Zambia Ambassador to EU & UN Aviation, Rwandair, Starbow (Ghana), Equajet (Congo, Brazzaville), Air Cote d’Ivoire, Mauritanie Dr. Ousmane Sylla Airlines (Mauritanie), DanaAir (Nigeria), Medview Air (Nigeria), First Nation Air (Nigeria), SN2AG Fmr. Guinean Minister of Mines (Gabon), Africa World Air (Ghana), CEIBA Intercontinental (Equatorial. Guinea), Discovery Air H.E. Mamadouba Max Bangoura (Nigeria), and Overland (Nigeria) among others could be imperiled if air transportations services Fmr. -

Appendix 25 Box 31/3 Airline Codes

March 2021 APPENDIX 25 BOX 31/3 AIRLINE CODES The information in this document is provided as a guide only and is not professional advice, including legal advice. It should not be assumed that the guidance is comprehensive or that it provides a definitive answer in every case. Appendix 25 - SAD Box 31/3 Airline Codes March 2021 Airline code Code description 000 ANTONOV DESIGN BUREAU 001 AMERICAN AIRLINES 005 CONTINENTAL AIRLINES 006 DELTA AIR LINES 012 NORTHWEST AIRLINES 014 AIR CANADA 015 TRANS WORLD AIRLINES 016 UNITED AIRLINES 018 CANADIAN AIRLINES INT 020 LUFTHANSA 023 FEDERAL EXPRESS CORP. (CARGO) 027 ALASKA AIRLINES 029 LINEAS AER DEL CARIBE (CARGO) 034 MILLON AIR (CARGO) 037 USAIR 042 VARIG BRAZILIAN AIRLINES 043 DRAGONAIR 044 AEROLINEAS ARGENTINAS 045 LAN-CHILE 046 LAV LINEA AERO VENEZOLANA 047 TAP AIR PORTUGAL 048 CYPRUS AIRWAYS 049 CRUZEIRO DO SUL 050 OLYMPIC AIRWAYS 051 LLOYD AEREO BOLIVIANO 053 AER LINGUS 055 ALITALIA 056 CYPRUS TURKISH AIRLINES 057 AIR FRANCE 058 INDIAN AIRLINES 060 FLIGHT WEST AIRLINES 061 AIR SEYCHELLES 062 DAN-AIR SERVICES 063 AIR CALEDONIE INTERNATIONAL 064 CSA CZECHOSLOVAK AIRLINES 065 SAUDI ARABIAN 066 NORONTAIR 067 AIR MOOREA 068 LAM-LINHAS AEREAS MOCAMBIQUE Page 2 of 19 Appendix 25 - SAD Box 31/3 Airline Codes March 2021 Airline code Code description 069 LAPA 070 SYRIAN ARAB AIRLINES 071 ETHIOPIAN AIRLINES 072 GULF AIR 073 IRAQI AIRWAYS 074 KLM ROYAL DUTCH AIRLINES 075 IBERIA 076 MIDDLE EAST AIRLINES 077 EGYPTAIR 078 AERO CALIFORNIA 079 PHILIPPINE AIRLINES 080 LOT POLISH AIRLINES 081 QANTAS AIRWAYS -

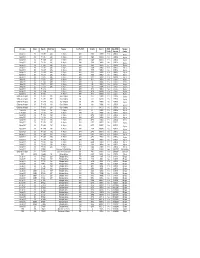

Final AFI RVSM Approvals 05 June 08

Mfr & Type Variant Reg. No. Build Year Operator Acft Op ICAO Serial No Mode S RVSM Date RVSM Operator Yes/No Approval Country Boeing 737 800 7T - VJK 2000 Air Algérie DAH 30203 0A0019 Yes 23/01/02 Algeria Boeing 737 800 7T - VJL 2000 Air Algérie DAH 30204 0A001A Yes 23/01/02 Algeria Boeing 737 800 7T - VJM 2000 Air Algérie DAH 30205 0A001B Yes 23/01/02 Algeria Boeing 737 800 7T - VJN 2000 Air Algérie DAH 30206 0A0020 Yes 23/01/02 Algeria Boeing 737 800 7T - VJQ 2002 Air Algérie DAH 30207 0A0021 Yes 23/01/02 Algeria Boeing 737 800 7T - VJP 2001 Air Algérie DAH 30208 0A0022 Yes 23/01/02 Algeria Boeing 737 600 7T - VJR 2002 Air Algérie DAH 30545 0A0025 Yes 01/06/02 Algeria Boeing 737 600 7T - VJS 2002 Air Algérie DAH 30210 0A0026 Yes 18/06/02 Algeria Boeing 737 600 7T - VJT 2002 Air Algérie DAH 30546 0A0027 Yes 18/06/02 Algeria Boeing 737 600 7T - VJU 2002 Air Algérie DAH 30211 0A0028 Yes 06/07/02 Algeria Airbus 330 202 7T - VJV 2005 Air Algérie DAH 0644 0A0044 Yes 31/01/05 Algeria Airbus 330 202 7T - VJW 2005 Air Algérie DAH 647 0A0045 Yes 05/03/05 Algeria Airbus 330 202 7T - VJY 2005 Air Algérie DAH 653 0A0047 Yes 20/03/05 Algeria Airbus 330 202 7T - VJX 2005 Air Algérie DAH 650 0A0046 Yes 20/03/05 Algeria Boeing 737 800 7T - VKA Air Algérie DAH 34164 0A0049 Yes 23/07/05 Algeria Boeing 737 800 7T - VKB Air Algérie DAH 34165 0A004A Yes 22/08/05 Algeria Boeing 737 800 7T - VKC Air Algérie DAH 34166 0A004B Yes 24/08/05 Algeria Gulfstream Aerospace SP 7T - VPC 2001 Gouv of Algeria IGA 1418 0A4009 Yes 27/07/05 Algeria Gulfstream Aerospace SP -

08-06-2021 Airline Ticket Matrix (Doc 141)

Airline Ticket Matrix 1 Supports 1 Supports Supports Supports 1 Supports 1 Supports 2 Accepts IAR IAR IAR ET IAR EMD Airline Name IAR EMD IAR EMD Automated ET ET Cancel Cancel Code Void? Refund? MCOs? Numeric Void? Refund? Refund? Refund? AccesRail 450 9B Y Y N N N N Advanced Air 360 AN N N N N N N Aegean Airlines 390 A3 Y Y Y N N N N Aer Lingus 053 EI Y Y N N N N Aeroflot Russian Airlines 555 SU Y Y Y N N N N Aerolineas Argentinas 044 AR Y Y N N N N N Aeromar 942 VW Y Y N N N N Aeromexico 139 AM Y Y N N N N Africa World Airlines 394 AW N N N N N N Air Algerie 124 AH Y Y N N N N Air Arabia Maroc 452 3O N N N N N N Air Astana 465 KC Y Y Y N N N N Air Austral 760 UU Y Y N N N N Air Baltic 657 BT Y Y Y N N N Air Belgium 142 KF Y Y N N N N Air Botswana Ltd 636 BP Y Y Y N N N Air Burkina 226 2J N N N N N N Air Canada 014 AC Y Y Y Y Y N N Air China Ltd. 999 CA Y Y N N N N Air Choice One 122 3E N N N N N N Air Côte d'Ivoire 483 HF N N N N N N Air Dolomiti 101 EN N N N N N N Air Europa 996 UX Y Y Y N N N Alaska Seaplanes 042 X4 N N N N N N Air France 057 AF Y Y Y N N N Air Greenland 631 GL Y Y Y N N N Air India 098 AI Y Y Y N N N N Air Macau 675 NX Y Y N N N N Air Madagascar 258 MD N N N N N N Air Malta 643 KM Y Y Y N N N Air Mauritius 239 MK Y Y Y N N N Air Moldova 572 9U Y Y Y N N N Air New Zealand 086 NZ Y Y N N N N Air Niugini 656 PX Y Y Y N N N Air North 287 4N Y Y N N N N Air Rarotonga 755 GZ N N N N N N Air Senegal 490 HC N N N N N N Air Serbia 115 JU Y Y Y N N N Air Seychelles 061 HM N N N N N N Air Tahiti 135 VT Y Y N N N N N Air Tahiti Nui 244 TN Y Y Y N N N Air Tanzania 197 TC N N N N N N Air Transat 649 TS Y Y N N N N N Air Vanuatu 218 NF N N N N N N Aircalin 063 SB Y Y N N N N Airlink 749 4Z Y Y Y N N N Alaska Airlines 027 AS Y Y Y N N N Alitalia 055 AZ Y Y Y N N N All Nippon Airways 205 NH Y Y Y N N N N Amaszonas S.A. -

Analyzing the Case of Kenya Airways by Anette Mogaka

GLOBALIZATION AND THE DEVELOPMENT OF THE AIRLINE INDUSTRY: ANALYZING THE CASE OF KENYA AIRWAYS BY ANETTE MOGAKA UNITED STATES INTERNATIONAL UNIVERSITY - AFRICA SPRING 2018 GLOBALIZATION AND THE DEVELOPMENT OF THE AIRLINE INDUSTRY: ANALYZING THE CASE OF KENYA AIRWAYS BY ANETTE MOGAKA A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE SCHOOL OF HUMANITIES AND SOCIAL STUDIES (SHSS) IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENT FOR THE AWARD OF MASTER OF ARTS DEGREE IN INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS UNITED STATES INTERNATIONAL UNIVERSITY - AFRICA SUMMER 2018 STUDENT DECLARATION I declare that this is my original work and has not been presented to any other college, university or other institution of higher learning other than United States International University Africa Signature: ……………………… Date: ………………………… Anette Mogaka (651006) This thesis has been submitted for examination with my approval as the appointed supervisor Signature: …………………. Date: ……………………… Maurice Mashiwa Signature: …………………. Date: ……………………… Prof. Angelina Kioko Dean, School of Humanities and Social Sciences Signature: …………………. Date: ……………………… Amb. Prof. Ruthie C. Rono, HSC Deputy Vice Chancellor Academic and Student Affairs. ii COPYRIGHT This thesis is protected by copyright. Reproduction, reprinting or photocopying in physical or electronic form are prohibited without permission from the author © Anette Mogaka, 2018 iii ABSTRACT The main objective of this study was to examine how globalization had affected the development of the airline industry by using Kenya Airways as a case study. The specific objectives included the following: To examine the positive impact of globalization on the development of Kenya Airways; To examine the negative impact of globalization on the development of Kenya Airways; To examine the effect of globalization on Kenya Airways market expansion strategies. -

Strategic Alternatives for the Continued Operation of Kenya Airways

STRATEGIC ALTERNATIVES FOR THE CONTINUED OPERATION OF KENYA AIRWAYS BY RAHAB NYAWIRA MUCHEMI UNITED STATES INTERNATIONAL UNIVERSITY SPRING 2016 STRATEGIC ALTERNATIVES FOR THE CONTINUED OPERATION OF KENYA AIRWAYS BY RAHAB NYAWIRA MUCHEMI A Project Report Submitted to the Chandaria School of Business in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirement for the Degree of Masters in Business Administration (MBA) UNITED STATES INTERNATIONAL UNIVERSITY SPRING 2016 ii STUDENT’S DECLARATION I, the undersigned, declare that this is my original work and has not been submitted to any other college, institution or university other than the United States International University in Nairobi for academic credit. Signed: ________________________ Date: _____________________ Rahab Nyawira Muchemi (ID 629094) This project has been presented for examination with my approval as the appointed supervisor. Signed: ________________________ Date: _____________________ Dr. Michael Kirubi, PhD. Signed: _______________________ Date: ____________________ Dean, Chandaria School of Business Signed: _______________________ Date: _________________ Deputy Vice Chancellor, Academic Affairs iii COPYRIGHT © 2016 Rahab Nyawira Muchemi. All rights reserved iv ABSTRACT The concept of strategic alternatives has received a lot of attention from scholars for a very long time now. Despite numerous studies in this area, interest has not faded away. To this end, the objectives of this study were to identify the determinants of strategic alternatives to better understand what drives airlines into such alliances and to identify factors that affect the performance of the alliances. The research was done through descriptive survey design, which involved all airlines with scheduled flights in and out of Kenya totaling thirty six (42). The target population was CEOs or senior managers within the airlines, which had response rate of 92.7%. -

Prof. Paul Stephen Dempsey

AIRLINE ALLIANCES by Paul Stephen Dempsey Director, Institute of Air & Space Law McGill University Copyright © 2008 by Paul Stephen Dempsey Before Alliances, there was Pan American World Airways . and Trans World Airlines. Before the mega- Alliances, there was interlining, facilitated by IATA Like dogs marking territory, airlines around the world are sniffing each other's tail fins looking for partners." Daniel Riordan “The hardest thing in working on an alliance is to coordinate the activities of people who have different instincts and a different language, and maybe worship slightly different travel gods, to get them to work together in a culture that allows them to respect each other’s habits and convictions, and yet work productively together in an environment in which you can’t specify everything in advance.” Michael E. Levine “Beware a pact with the devil.” Martin Shugrue Airline Motivations For Alliances • the desire to achieve greater economies of scale, scope, and density; • the desire to reduce costs by consolidating redundant operations; • the need to improve revenue by reducing the level of competition wherever possible as markets are liberalized; and • the desire to skirt around the nationality rules which prohibit multinational ownership and cabotage. Intercarrier Agreements · Ticketing-and-Baggage Agreements · Joint-Fare Agreements · Reciprocal Airport Agreements · Blocked Space Relationships · Computer Reservations Systems Joint Ventures · Joint Sales Offices and Telephone Centers · E-Commerce Joint Ventures · Frequent Flyer Program Alliances · Pooling Traffic & Revenue · Code-Sharing Code Sharing The term "code" refers to the identifier used in flight schedule, generally the 2-character IATA carrier designator code and flight number. Thus, XX123, flight 123 operated by the airline XX, might also be sold by airline YY as YY456 and by ZZ as ZZ9876. -

22 the East African Directorate of Civil Aviation

NOT FOR PUBLICATION INSTITUTE OF CURRENT WORLD AFFAIRS B- 67 Wsshlngton, D.C. ast Africa High Commission: November 2, 195/ (22) The ast African Directorate of Civil Aviation Mr. Walter S. Roers Institute of Current World Affairs 522 Fifth Avenue New York 6, New York Dear Mr. Rogers The considerable size of Best Afr, ica, with populated centers separated by wide tracts of rugged, poorly watered country through which road and rail routes are built with difficulty and then provide only slow service, gives air transport an important position in the economy of the area. Access to ast Africa from rope and elsewhere in the world is aso greatly enhanced by air transport, which need not follow the deviating contours of the continent. Businesses with b:'enches throughout @set Africa need fast assenger services to carry executives on supervisory visits; perishable commodities, important items for repair of key machlner, and )ivestock for breeding purposes provide further traffic; and a valuable tourist traffic is much dependent upon air transport. The direction and coordination of civil aviation, to help assure the quality and amplitude of aerodromes, aeraio directiona and communications methods, and aircraft safety standards, is an important responsibility which logically fsIs under a central authority. This central authority is the Directorate of Oivil Aviation, a department of the ast Africa High Commission. The Directorate, as an interterritorlal service already in existence, came under the administration of the High Oommisslon on its effective date of inception, January I, 98, an more specifically under the Commissioner for Transport, one of the four principal executive officers of the High Commission, on May I, 199. -

SAMSON MUUO MUSYOKI FINAL PROJECT.Pdf

ORGANIZATIONAL RESOURCES, STRATEGY, AND ENVIRONMENTAL TURBULENCE IN KENYA AIRWAYS LIMITED SAMSON MUUO MUSYOKI A RESEARCH PROJECT SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENT FOR THE AWARD OF THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF BUSINESS ADMINISTRATION, SCHOOL OF BUSINESS, UNIVERSITY OF NAIROBI JUNE 2018 DECLARATION The project is my original work and has not been presented for a degree or any other award in any other institution. Signature: ……………………………. Date: ……………………………..... SAMSON MUUO MUSYOKI D61/70088/2008 Declaration by the Supervisor This project has been submitted for examination with my approval as University Supervisor. Signature: ……………………………. Date: ……………………………..... PROFESSOR Z.B.AWINO School of Business University of Nairobi ii DEDICATION I dedicate this project to my dear wife Leah Kavinya Muuo and our daughter Shani Mutheu Muuo; you have been a source of strength and comfort throughout this journey. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENT The task of producing this report from inception to submission for examination would not have been successful without the support of several parties; I am greatly indebted to them for their role throughout this period. First is to thank the Almighty God for enabling me to undertake this project. Every being in me resonate His love and favor in the various stages of this project; all glory and honor go to Yahweh. Secondly is the intellectual support and guidance I got from the University supervisor, Professor Z.B Awino. Your involvement in every step I had to make towards this achievement was of great assistance. The financial, emotional, and moral support I got from my wife Leah and our daughter Shani is another immeasurable contribution towards the completion of this report. -

Avianca in Brazil

REFERENCE GUIDE 2015 STAR ALLIANCE WELCOMES AVIANCA IN BRAZIL FOR EMPLOYEES OF STAR ALLIANCE MEMBER CARRIERS 18th Edition, July 2015 WELCOME WELCOME TO THE 2015 EDITION OF THE STAR ALLIANCE REFERENCE GUIDE This edition includes baggage, airport and frequent flyer information for our newest member, Avianca in Brazil. Its flights, operated under the Avianca logo and the O6 two-letter code, add new unique destinations in the fast-growing Brazilian market. The addition of Avianca in Brazil brings the Star Alliance membership to 28 airlines. This guide is designed to provide a user-friendly tool that gives quick access to the information needed to deliver a smoother travel experience to international travellers. Information changes regularly, so please continue to consult your airline’s publications and information systems for changes and updates, as well as for operational information and procedures. We welcome your feedback at [email protected]. Thank you, Star Alliance Internal Communications 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS OVERVIEW AIRPORTS INFORMATION 68 Welcome 2 Priority Baggage Handling 69 Greetings from Avianca in Brazil 4 Free Checked Baggage Allowances 70 Vision / Mission 5 Special Checked Baggage 75 Facts & Figures 6 Carry-on Baggage Policy 133 Irregular Operations Handling 134 GENERAL INFORMATION 10 Interline E-Ticketing FAQ - Airports 139 Customer Benefits 11 Frequent Flyer Programmes 15 Reservation Call Centres 19 LOUNGE INFORMATION 141 Reservations Special Service Items 51 Lounge Access 142 Booking Class Alignment 53 Lounge Access Chart 148 Ticketing Procedures 60 Destinations with Lounges 151 Interline E-Ticket FAQ - Reservations 64 GDS Access Codes 67 MAJOR AIRPORT MAPS 173 World Time Zones 254 Star Alliance Services GmbH, Frankfurt Airport Centre, Main Lobby, D-60546 Frankfurt∕Main Vice-President, Director, Internal Editor Layout Photography Corporate Office Communication Garry Bridgewater, Rachel Niebergal, Ted Fahn, British Airports Authority Christian Klick Janet Northcote Sherana Productions Peridot Design Inc. -

Report Afraa 2016

AAFRA_PrintAds_4_210x297mm_4C_marks.pdf 1 11/8/16 5:59 PM www.afraa.org Revenue Optimizer Optimizing Revenue Management Opportunities C M Y CM MY CY CMY K Learn how your airline can be empowered by Sabre Revenue Optimizer to optimize all LINES A ® IR SSO A MPAGNIE S AER CO IEN C N ES N I A D ES A N A T C IO F revenue streams, maximize market share I T R I I O R IA C C A I N F O N S E S A S A ANNUAL and improve analyst productivity. REPORT AFRAA 2016 www.sabreairlinesolutions.com/AFRAA_TRO ©2016 Sabre GLBL Inc. All rights reserved. 11/16 AAFRA_PrintAds_4_210x297mm_4C_marks.pdf 2 11/8/16 5:59 PM How can airlines unify their operations AFRAA Members AFRAA Partners and improve performance? American General Supplies, Inc. Simplify Integrate Go Mobile C Equatorial Congo Airlines LINKHAM M SERVICES PREMIUM SOLUTIONS TO THE TRAVEL, CARD & FINANCIAL SERVICE INDUSTRIES Y CM MY CY CMY K Media Partners www.sabreairlinesolutions.com/AFRAA_ConnectedAirline CABO VERDE AIRLINES A pleasurable way of flying. ©2016 Sabre GLBL Inc. All rights reserved. 11/16 LINES AS AIR SO N C A IA C T I I R O F N A AFRICAN AIRLINES ASSOCIATION ASSOCIATION DES COMPAGNIES AÉRIENNES AFRICAINES AFRAA AFRAA Executive Committee (EXC) Members 2016 AIR ZIMBABWE (UM) KENYA AIRWAYS (KQ) PRESIDENT OF AFRAA CHAIRMAN OF THE EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE Captain Ripton Muzenda Mr. Mbuvi Ngunze Chief Executive Officer Group Managing Director and Chief Executive Officer Air Zimbabwe Kenya Airways AIR BURKINA (2J) EGYPTAIR (MS) ETHIOPIAN AIRLINES (ET) Mr. -

Sabre and South African Airways Sign New Multi-Year Technology Agreement

October 27, 2014 Sabre and South African Airways sign new multi-year technology agreement Airline to make all fares and inventory available in the Sabre travel marketplace JOHANNESBURG, Oct. 27, 2014 /PRNewswire/ -- Sabre Corporation and South African Airways have signed a new multi-year agreement to make the carrier's airfares and inventory available in the Sabre global distribution system. The agreement provides Sabre travel agencies and corporations globally with access to the airline's full range of fares, schedules and availability including published fares sold through the airline's own website and reservations offices. "We have a long and successful partnership with South African Airways to market and sell their products and services, and to support their expansion and growth in new markets," said Greg Webb, president, Sabre Travel Network. "South Africa is an important new market for Sabre and we are especially pleased to renew our agreement at a time we are seeing strong interest from the industry." Sylvain Bosc, chief commercial officer at South African Airways said: "Sabre is an important technology partner for us, which has been strengthened by their launch and growth in South Africa, and across the African continent. Sabre provides us with an easy and efficient way to market and sell our fares the way we want to, and continues to be a very valuable channel for reaching high-yielding corporate travelers." Sabre's travel marketplace plays an important role in facilitating the marketing and sale of airfares, ancillary services, hotel rooms, rental cars, rail tickets and other types of travel, to more than 400,000 travel agents and thousands of corporations who use it to shop, book and manage travel.