Idaho Archaeologist

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

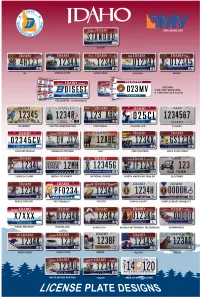

To See a Complete List of All Special Plates Types Available

2021 SPECIAL LICENSE PLATE FUND INFORMATION Plate Program Fund Name Responsible Organization (Idaho Code) Program Purpose Friends of 4-H Division University of Idaho Foundation 4H (49-420M) Funds to be used for educational events, training materials for youth and leaders, and to better prepare Idaho youth for future careers. Agriculture Ag in the Classroom Account Department of Agriculture (49-417B) Develop and present an ed. program for K-12 students with a better understanding of the crucial role of agriculture today, and how Idaho agriculture relates to the world. Appaloosa N/A Appaloosa Horse Club (49-420C) Funding of youth horse programs in Idaho. Idaho Aviation Foundation Idaho Aviation Association Aviation (49-420K) Funds use by the Idaho Aviation Foundation for grants relating to the maintenance, upgrade and development of airstrips and for improving access and promoting safety at backcountry and recreational airports in Idaho. N/A - Idaho Department of Parks and Recreation Biking (49-419E) Funds shall be used exclusively for the preservation, maintenance, and expansion of recreational trails within the state of Idaho and on which mountain biking is permitted. Capitol Commission Idaho Capitol Endowment Income Fund – IC 67-1611 Capitol Commission (49-420A) To help fund the restoration of the Idaho Capitol building located in Boise, Idaho. Centennial Highway Distribution Account Idaho Transportation Department (49-416) All revenue shall be deposited in the highway distribution account. Choose Life N/A Choose Life Idaho, Inc. (49-420R) To help support pregnancy help centers in Idaho. To engage in education and support of adoption as a positive choice for women, thus encouraging alternatives to abortion. -

10. Palouse Prairie Section

10. Palouse Prairie Section Section Description The Palouse Prairie Section, part of the Columbia Plateau Ecoregion, is located along the western border of northern Idaho, extending west into Washington (Fig. 10.1, Fig. 10.2). This section is characterized by dissected loess-covered basalt plains, undulating plateaus, and river breaks. Elevation ranges from 220 to 1,700 m (722 to 5,577 ft). Soils are generally deep, loamy to silty, and have formed in loess, alluvium, or glacial outwash. The lower reaches and confluence of the Snake and Clearwater rivers are major waterbodies. Climate is maritime influenced. Precipitation ranges from 25 to 76 cm (10 to 30 in) annually, falling primarily during the fall, winter, and spring, and winter precipitation falls mostly as snow. Summers are relatively dry. Average annual temperature ranges from 7 to 12 ºC (45 to 54 ºF). The growing season varies with elevation and lasts 100 to 170 days. Population centers within the Idaho portion of the section are Lewiston and Moscow, and small agricultural communities are dispersed throughout. Outdoor recreational opportunities include hunting, angling, hiking, biking, and wildlife viewing. The largest Idaho Palouse Prairie grassland remnant on Gormsen Butte, south of Department of Fish and Moscow, Idaho with cropland surrounding © 2008 Janice Hill Game (IDFG) Wildlife Management Area (WMA) in Idaho, Craig Mountain WMA, is partially located within this section. The deep and highly-productive soils of the Palouse Prairie have made dryland farming the primary land use in this section. Approximately 44% of the land is used for agriculture with most farming operations occurring on private land. -

Geologic Map of the Grangeville East Quadrangle, Idaho County, Idaho

IDAHO GEOLOGICAL SURVEY DIGITAL WEB MAP 86 MOSCOW-BOISE-POCATELLO SCHMIDT AND OTHERS Sixmile Creek pluton to the north near Orofino (Lee, 2004) and an age of indicate consistent dextral, southeast-side-up shear sense across this zone. REFERENCES GEOLOGIC MAP OF THE GRANGEVILLE EAST QUADRANGLE, IDAHO COUNTY, IDAHO CORRELATION OF MAP UNITS about 118 Ma in tonalite in the Hazard Creek complex to the south near Thus, the prebasalt history along this structure was likely oblique, dextral- McCall (Manduca and others, 1993). reverse shear that appears to offset the accreted terrane-continent suture Anderson, A.L., 1930, The geology and mineral resources of the region about zone by several miles in the adjoining Harpster quadrangle to the east. Orofino, Idaho: Idaho Geological Survey Pamphlet 34, 63 p. Quartz porphyry (Permian to Cretaceous)Quartz-phyric rock that is probably Artificial Alluvial Mass Movement Volcanic Rocks Intrusive Island-Arc Metavolcanic KPqp Barker, F., 1979, Trondhjemite: definition, environment, and hypotheses of origin, a shallow intrusive body. Highly altered and consists almost entirely of To the southeast of the Mt. Idaho shear zone, higher-grade, hornblende- Disclaimer: This Digital Web Map is an informal report and may be Deposits Deposits Deposits Rocks and Metasedimentary Rocks in Barker, F., ed., Trondhjemites, Dacites, and Related Rocks, Elsevier, New Keegan L. Schmidt, John D. Kauffman, David E. Stewart, quartz, sericite, and iron oxides. Historic mining activity at the Dewey Mine dominated gneiss and schist and minor marble (JPgs and JPm) occur along revised and formally published at a later time. Its content and format m York, p. -

Idaho County School Survey Report PSLLC

CULTURAL RESOURCE SURVEY HISTORIC RURAL SCHOOLS OF IDAHO COUNTY Prepared for IDAHO COUNTY HISTORIC PRESERVATION COMMISSION GRANGEVILLE, IDAHO By PRESERVATION SOLUTIONS LLC September 1, 2013 TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements ..................................................................................................................... 1 Introduction ................................................................................................................................. 2 Preface: What is a Cultural Resource Survey? ........................................................................... 3 Methodology Survey Objectives ........................................................................................................... 4 Scope of Work ................................................................................................................. 7 Survey Findings Dates of Construction .................................................................................................... 12 Functional Property Types ............................................................................................. 13 Building Forms .............................................................................................................. 13 Architectural Styles ........................................................................................................ 19 Historic Contexts Idaho County: A Development Overview: 1860s to 1950s ............................................. 24 Education in Idaho County: 1860s to -

Geologic Map of IDAHO

Geologic Map of IDAHO 2012 COMPILED BY Reed S. Lewis, Paul K. Link, Loudon R. Stanford, and Sean P. Long Geologic Map of Idaho Compiled by Reed S. Lewis, Paul K. Link, Loudon R. Stanford, and Sean P. Long Idaho Geological Survey Geologic Map 9 Third Floor, Morrill Hall 2012 University of Idaho Front cover photo: Oblique aerial Moscow, Idaho 83843-3014 view of Sand Butte, a maar crater, northeast of Richfield, Lincoln County. Photograph Ronald Greeley. Geologic Map Idaho Compiled by Reed S. Lewis, Paul K. Link, Loudon R. Stanford, and Sean P. Long 2012 INTRODUCTION The Geologic Map of Idaho brings together the ex- Map units from the various sources were condensed tensive mapping and associated research released since to 74 units statewide, and major faults were identified. the previous statewide compilation by Bond (1978). The Compilation was at 1:500,000 scale. R.S. Lewis com- geology is compiled from more than ninety map sources piled the northern and western parts of the state. P.K. (Figure 1). Mapping from the 1980s includes work from Link initially compiled the eastern and southeastern the U.S. Geological Survey Conterminous U.S. Mineral parts and was later assisted by S.P. Long. County geo- Appraisal Program (Worl and others, 1991; Fisher and logic maps were derived from this compilation for the others, 1992). Mapping from the 1990s includes work Digital Atlas of Idaho (Link and Lewis, 2002). Follow- by the U.S. Geological Survey during mineral assess- ments of the Payette and Salmon National forests (Ev- ing the county map project, the statewide compilation ans and Green, 2003; Lund, 2004). -

Environmental Degradation, Resource War, Irrigation and the Transformation of Culture on Idaho's Snake River Plain, 1805--1927

UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones 12-2011 Newe country: Environmental degradation, resource war, irrigation and the transformation of culture on Idaho's Snake River plain, 1805--1927 Sterling Ross Johnson University of Nevada, Las Vegas Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/thesesdissertations Part of the Military History Commons, Social History Commons, and the United States History Commons Repository Citation Johnson, Sterling Ross, "Newe country: Environmental degradation, resource war, irrigation and the transformation of culture on Idaho's Snake River plain, 1805--1927" (2011). UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones. 1294. http://dx.doi.org/10.34917/2838925 This Thesis is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by Digital Scholarship@UNLV with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Thesis in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Thesis has been accepted for inclusion in UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones by an authorized administrator of Digital Scholarship@UNLV. For more information, please contact [email protected]. NEWE COUNTRY: ENVIRONMENTAL DEGRADATION, RESOURCE WAR, IRRIGATION AND THE TRANSFORMATION -

Metal Truss Highway Bridges of Idaho

NPS Form 10-900-b 0MB No. 1024-0018 (June 1991) RECEIVED 2?80 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service 3 | 200I National Register of Historic Place Multiple Property Documentation Form This form is used for documenting multiple property groups relating to one or several historic contexts. See Instructions in How to Complete the Multiple Property Documention Form (National Register Bulletin 16B). Complete each item by entering the requested information for additional space, use continuation sheets (Form 10-900-a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer to complete all items. X New Submission Amended Submission Metal Truss Highway Bridges of Idaho Historic Highway Bridges of Idaho. 1890-1960 name/title Donald W. Watts. Preservation Planner organization Idaho SHPO date August 10. 2000 street & number 210 Main Street _ telephone (208) 334-3861 city or town Boise state ID zip code 83702 As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this documentation form meets the National Register documentation standards and sets forth requirements for the listing of related properties consistent with the National Register criteria. This submission meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60 and the Secretary of the Interior's Standards and Guidelines for Archaeology and Historic Preservation. C. Reid, Ph.D. U Date State Historic Preservation Officer Idaho State Historic Preservation Office State or Federal agency and bureau I, hereby, certify that this multiple property documentation form has been approved by the National Register as a basis for evaluating related aroperties for Ijatirig in the/National Rj^c /ter. -

Vista Neighborhood Historic Context

VISTA NEIGHBORHOOD HISTORIC CONTEXT TAG Historical Research & Consulting VISTA NEIGHBORHOOD CONTEXT Prepared for City of Boise Planning and Development Services By TAG HISTORICAL RESEARCH & CONSULTING a/b/n of The Arrowrock Group, Inc. September 2015 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Project Background......................................................................................................3 Introduction..................................................................................................................4 Neighborhood Roots 1863 – 1905............................................................................4 Early Land Ownership and Development (1890-1910)........................................6 The Eagleson Family.....................................................................................................8 Transportation Networks and Streetcar Suburbs.................................................12 Early 20th Century Architectural Styles..................................................................14 School and Community Life........................................................................................14 Growth and Development...........................................................................................15 Large Lots and Open Spaces........................................................................................20 Growing Pains................................................................................................................22 The Mid-Century Building Boom................................................................................24 -

Contributions to Economic Geology, 1930

CONTRIBUTIONS TO ECONOMIC GEOLOGY, 1930 PART 1. METALS AND NONMETALS EXCEPT FUELS A GRAPHIC HISTORY OF METAL MINING IN IDAHO By CLYDE P. Ross ABSTRACT In this paper the mining history of Idaho is reviewed by means of three statistical charts which show that there was considerable placer mining in the sixties, that a depression in all mining occurred in the seventies, that lode mining started in the eighties, and that the mining of lead-silver ore soon became the dominant factor in the industry. Improvements in ore dressing have recently caused some increase in the production of zinc. The production of copper, never large, reached its peak in 1907 and has since been declining. Shoshone County has been the outstanding producer almost since the first discovery of the deposits of the Coeur d'Alene district and in 1926 produced nearly 94 per cent of the total for the State. Boise and Idaho Counties were the dominant producers in the early placer days but have since been relatively unimportant. Blaine, Custer, and Lemhi Counties had large production in the eighties, and each has had a revival since 1900. Custer County, the least productive of the three in the early days, has had the most encouraging revival, but the formerly famous Blaine County had the smallest and most delayed re vival of the three. Owyhee County had an early placer boom, followed by active production from lodes in 1867 to 1876 and again in 1889 to 1914, the longest period of mining prosperity anywhere in Idaho outside of Shoshone County. Production in each of the counties, except Shoshone County, has been governed primarily by discovery of ore and only secondarily by economic factors, and in most counties the quantity found in any one period was small. -

The Unsung Trapdoor Rifle

http://rockislandauction.blogspot.com/2013/10/the-unsung-trapdoor-rifle.html The Unsung Trapdoor Rifle Written by Joel Kolander at Rock Island Auction Company, Friday, October 25, 2013 - http://www.rockislandauction.com/ Reprinted on the VGCA website with permission of Joel Kolander and Rock Island Auction Company. All photographs are courtesy of Rock Island Auction Company. In terms of American military long arms very little attention is given to a predecessor of the much heralded M1903 and M1 Garand, the Springfield Trapdoor. The Springfield Trapdoor was produced for over 20 years and would experience many changes throughout its life. The rifle would take its place in history just after the Civil War, despite the justifiable hesitation of many military personnel who were all too aware about the superiority of repeaters and magazine fed rifles. It would kill buffalo by the thousands as America expanded westward and would also play a role in the wars against the Native Americans. Militarily it represents the watershed transition for U.S. forces from the musket to the rifle. Today we find out a little bit more of this rifle, its origins, the question of its performance, and its role in history. Lot 3507: Rare Early Springfield Armory Model 1873 Trapdoor Rifle with Rare Metcalfe Device Origins After the Civil War, the War Department wanted a breech-loading rifle. To be specific, they wanted a breech-loading rifle that would chamber a self-primed, metallic cartridge. This led to the formation of an Army Board who, in 1865, would host trials of different rifles by makers both foreign and domestic. -

History of Silver City, Idaho

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 1951 History of Silver City, Idaho Betty Belle Derig The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Derig, Betty Belle, "History of Silver City, Idaho" (1951). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 2567. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/2567 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. .. A Of - iaaàwR;* 40%*;% ay*#** ;/.:' tar ': A MtaHMJBleiM^atifH^kcIS Ik UMI Number" EP34753 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent on the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dtoêrtatien P*iMish«a UMI EP34753 Copyright 2012 by ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This edition of the work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. uest* ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106 -1346 tot " ' ::: V -" - jWRaw,,Q*M jW%&aaW#B;'::. %&/, 4W laaibDs «*i**o%3%p8 :& 6fi umimx Hood aai *01. -

Real Estate Service for North Central Idaho

EXPERIENCE North Central Visitor’s Guide | 2016 | 2017 2 EXPERIENCE NORTH CENTRAL IDAHO 4 Idaho County 10 Osprey: Birds of Prey 12 Clearwater County 16 US Highway 12 Waterfalls 22 Lewis County From the deepest gorge in 28 Heart of the Monster: History of the Nimiipuu North America to the prairies of harvest 34 Nez Perce County (and everything else in between). 39 The Levee Come explore with us. SARAH S. KLEMENT, 42-44Dining Guide PUBLISHER Traveling On? Regional Chamber Directory DAVID P. RAUZI, 46 EDITOR CONTRIBUTED PHOTO: MICHELLE FORD COVER PHOTO BY ROBERT MILLAGE. Advertising Inquires Submit Stories SARAH KLEMENT, PUBLISHER DAVID RAUZI, EDITOR Publications of Eagle Media Northwest [email protected] [email protected] 900 W. Main, PO Box 690, Grangeville ID 83530 DEB JONES, PUBLISHER (MONEYSAVER) SARAH KLEMENT, PUBLISHER 208-746-0483, Lewiston; 208-983-1200, Grangeville [email protected] [email protected] EXPERIENCE NORTH CENTRAL IDAHO 3 PHOTO BY ROBERT MILLAGE 4 EXPERIENCE NORTH CENTRAL IDAHO PHOTO BY SARAH KLEMENT PHOTO BY DAVID RAUZI A scenic view of the Time Zone Bridge greets those entering or leaving the Idaho County town of Riggins (above) while McComas Meadows (top, right) is a site located in the mountains outside of Harpster. (Right, middle) Hells Canyon is a popular fishing spot and (bottom, right) the Sears Creek area is home to a variety of wildlife, including this flock of turkeys. Idaho County — said to be named for the Steamer Idaho that was launched June 9, 1860, on the Columbia River — spans the Idaho PHOTO BY MOUNTAIN RIVER OUTFITTERS panhandle and borders three states, but imposing geography sets this area apart from the rest of the United States.