From Foreign Lands They Came History of the Potato Germans

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Og Fødevareudvalget 2016-17 MOF Alm.Del Endeligt Svar På Spørgsmål 776 Offentligt

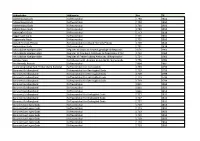

Miljø- og Fødevareudvalget 2016-17 MOF Alm.del endeligt svar på spørgsmål 776 Offentligt Liste over ansøgere om landbrugsstøtte, der i kalenderåret 2016 fik udbetalt 1 million kr. eller mere. CVR nr Navn Postnr By Beløb 18387999 2 K Kristensen I/S 6971 Spjald 1.204.370,57 30859340 4g I/S v/H. P. & G. Garth-Gruner 4100 Ringsted 1.840.847,70 56986111 A/S Saltbækvig 2970 Hørsholm 1.495.301,75 34455589 AB-AGRO ApS 9370 Hals 1.688.949,45 21802247 Abildskovgård ApS 5672 Broby 1.795.485,74 30554175 Abildtrup Agro ApS 7560 Hjerm 1.195.261,45 28970838 Adamshøj Gods A/S 4100 Ringsted 1.340.454,91 65110768 Adolf Friedrich Bossen 6270 Tønder 1.406.503,11 74823513 Advokat Henrik Skaarup 9700 Brønderslev 2.404.609,69 29657823 Agrifos I/S 4912 Harpelunde 3.726.461,23 36073209 Agro Seeds ApS 7870 Roslev 1.605.902,94 65328313 Aksel Lund 6280 Højer 1.399.805,49 26118182 Akset A/S 7323 Give 1.018.414,87 44210851 Aktivitetscenter Vestervig-Agger 7770 Vestervig 1.194.484,00 26779642 Albæk I/S 6900 Skjern 1.237.617,84 19470989 Alex Ostersen 6900 Skjern 1.622.978,43 21044237 Alfred Ebbesen 6780 Skærbæk 1.087.666,28 21767247 Alfred Kloster 7490 Aulum 1.101.410,01 58565717 Allan Jensen 4791 Borre 1.215.043,67 35590439 Allan Møller Koch 6500 Vojens 2.098.744,28 36556498 Almende ApS 6270 Tønder 2.475.146,19 17804502 Anders Christensen 4640 Faxe 1.200.120,61 25675274 Anders Christiansen 7570 Vemb 1.106.339,88 13971692 Anders D. -

Euriskodata Rare Book Series

THE LIBRARY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE HI S T KY o F SCANDINAVIA. HISTOEY OF SCANDINAVIA. gxm tilt €mI% f iiius NORSEMEN AND YIKINGS TO THE PRESENT DAY. BY THE EEV. PAUL C. SINDOG, OF COPENHAGEN. professor of t^e Scanlimafaian fLanguagts anD iLifnaturr, IN THE UNIVERSITY OF THE CITY OF NEW-YORK. Nonforte ac temere humana negotia aguntur atque volvuntur.—Curtius. SECOND EDITION. NEW-YORK: PUDNEY & RUSSELL, PUBLISHERS. 1859. Entered aceordinfj to Act of Congress, in the year 1858, By the rev. PAUL C. SIN DING, In the Clerk's Office of the District Court of the United States, for the Southern Distriftt of New-York. TO JAMES LENOX, ESQ., OF THE CUT OF NEW-TOBK, ^ht "^nu of "^ttttxs, THE CHIIISTIAN- GENTLEMAN, AND THE STRANGER'S FRIEND, THIS VOLUME IS RESPECTFULLY INSCRIBED, BY THE AUTHOR PREFACE. Although soon after my arrival in the city of New-York, about two years ago, learning by experience, what already long had been known to me, the great attention the enlightened popu- lation of the United States pay to science and the arts, and that they admit that unquestion- able truth, that the very best blessings are the intellectual, I was, however, soon . aware, that Scandinavian affairs were too little known in this country. Induced by that ardent patriotism peculiar to the Norsemen, I immediately re- solved, as far as it lay in my power, to throw some light upon this, here, almost terra incog- nita, and compose a brief History of Scandinavia, which once was the arbiter of the European sycjtem, and by which America, in reality, had been discovered as much as upwards of five Vlll PREFACE centuries before Columbus reached St. -

Lokalt Høringsnotat

Lokalt høringsnotat Forslag til vandplan for hovedvandopland 1.11, Lillebælt/Jylland Resumé og kommentering af høringssvar af lokal karakter Januar 2012 Lokalt høringsnotat for Hovedvandopland 1.11, Lillebælt/Jylland Indholdsfortegnelse 1.0 Indledning.....................................................................................................................................4 1.1 Høringsnotatets opbygning og indhold ..................................................................................4 2.0 Vandløb.........................................................................................................................................5 2.1 Resume ......................................................................................................................................5 2.2 Miljømål....................................................................................................................................6 2.3 Datagrundlag og fagligt grundlag ..........................................................................................7 2.4 Påvirkninger.............................................................................................................................9 2.5 Virkemidler og indsatsprogram ...........................................................................................11 2.5.1 Vandløbsrestaurering .....................................................................................................11 2.5.2 Ændret vandløbsvedligeholdelse ...................................................................................12 -

NOSOCOMIAL OUTBREAK of SCABIES in VIBORG COUNTY No

EPI-NEWS NATIONAL SURVEILLANCE OF COMMUNICABLE DISEASES Editor: Tove Rønne Statens Serum Institut - 5 Artillerivej - 2300 Copenhagen S - Denmark Tel.: +45 3268 3268 - Fax: +45 3268 3868 www.ssi.dk - [email protected] - ISSN: 1396-4798 NOSOCOMIAL OUTBREAK OF SCABIES IN VIBORG COUNTY No. 7, 2001 Fig. 1. Nosocomial outbreak of scabies in Viborg County, June 2000-January 2001 Index case Fellow patients Relatives / other Hospital / nursing home staff Home care staff Hospital, Mors Nursing home Nursing Hospital, Kjellerup Hospital, Home care, Mors Home Mors care, Hospital, Viborg Index case In the second week of October 2000 index case, who never left his single having scabies as part of an unbro- a sizeable nosocomial outbreak of room. Several of these patients ken chain of infection: the index scabies was noted at Nykøbing Mors passed the infestation on, Fig. 1. case, 24 fellow patients, 19 relatives, Hospital. The spread was presuma- Seven employees were infected. 13 hospital employees, eight nur- bly from a patient (the index case) Nearly all the patients who were in- sing-home employees, 11 home care admitted to a medical ward in mid- fected at the hospital during July- assistants and one other. The index July. This patient died 10 days later August were getting home nursing case and two fellow patients had sca- from a malignancy, and scabies was or lived in a nursing home. A total of bies norvegica, in which the number not suspected during the admission. 11 employees in six home-care dis- of scabies mites in the skin is many In mid-June the patient had spent tricts were infected. -

Skifteprotokoller, Sjælland

Skifteprotokoller, Sjælland Arkivskaber Arkivserie Fra Til Adelersborg Gods Skifteprotokol 1790 1850 Adelersborg Gods Skifteprotokol 1790 1850 Adelersborg Gods Skifteprotokol 1790 1850 Adelersborg Gods Skifteprotokol 1790 1850 Agersøgård Gods Skifteprotokol 1773 1818 Aggersvold Gods Skifteprotokol 1721 1850 Aggersvold Gods Skifteprotokol 1721 1850 Alsted Herreds Provsti Skifteprotokol for Alsted Herreds Provsti 1759 1814 Antvorskov Gods Skifteprotokol 1791 1818 Arkivskabte Hjælpemidler Register til Smørum Herreds gejstlige skifteprotok 1676 1960 Arkivskabte Hjælpemidler Register til Kronborg Amtstues skifteprotokol 1712 1712 1960 Arkivskabte Hjælpemidler Register til Frederiksborg Amtstues skifteprotokol 1724 1960 Arninge Sogn Skiftebreve vedr. Arninge præstekalds mensalgods 1776 1781 Ars Herreds Provsti Skifteprotokol 1804 1807 Asminderød-Grønholt-Fredensborg Pastorat Skifteprotokol for mensalgods 1799 1799 Baroniet Guldborgland Skifteprotokol for Berritsgård Gods 1719 1799 Baroniet Guldborgland Skifteprotokol for Berritsgård Gods 1719 1799 Baroniet Guldborgland Skifteprotokol for Berritsgård Gods 1719 1799 Baroniet Guldborgland Skifteprotokol for Berritsgård Gods 1719 1799 Baroniet Guldborgland Skifteprotokol 1811 1850 Baroniet Guldborgland Skifteprotokol 1811 1850 Baroniet Guldborgland Skifteprotokol 1811 1850 Baroniet Guldborgland Skifteprotokol for Orebygård Gods 1727 1811 Baroniet Guldborgland Skifteprotokol for Orebygård Gods 1727 1811 Baroniet Guldborgland Skifteprotokol for Orebygård Gods 1727 1811 Baroniet Juellinges Gods Skifteprotokol -

A Meta Analysis of County, Gender, and Year Specific Effects of Active Labour Market Programmes

A Meta Analysis of County, Gender, and Year Speci…c E¤ects of Active Labour Market Programmes Agne Lauzadyte Department of Economics, University of Aarhus E-Mail: [email protected] and Michael Rosholm Department of Economics, Aarhus School of Business E-Mail: [email protected] 1 1. Introduction Unemployment was high in Denmark during the 1980s and 90s, reaching a record level of 12.3% in 1994. Consequently, there was a perceived need for new actions and policies in the combat of unemployment, and a law Active Labour Market Policies (ALMPs) was enacted in 1994. The instated policy marked a dramatic regime change in the intensity of active labour market policies. After the reform, unemployment has decreased signi…cantly –in 1998 the unemploy- ment rate was 6.6% and in 2002 it was 5.2%. TABLE 1. UNEMPLOYMENT IN DANISH COUNTIES (EXCL. BORNHOLM) IN 1990 - 2004, % 1990 1992 1994 1996 1998 2000 2002 2004 Country 9,7 11,3 12,3 8,9 6,6 5,4 5,2 6,4 Copenhagen and Frederiksberg 12,3 14,9 16 12,8 8,8 5,7 5,8 6,9 Copenhagen county 6,9 9,2 10,6 7,9 5,6 4,2 4,1 5,3 Frederiksborg county 6,6 8,4 9,7 6,9 4,8 3,7 3,7 4,5 Roskilde county 7 8,8 9,7 7,2 4,9 3,8 3,8 4,6 Western Zelland county 10,9 12 13 9,3 6,8 5,6 5,2 6,7 Storstrøms county 11,5 12,8 14,3 10,6 8,3 6,6 6,2 6,6 Funen county 11,1 12,7 14,1 8,9 6,7 6,5 6 7,3 Southern Jutland county 9,6 10,6 10,8 7,2 5,4 5,2 5,3 6,4 Ribe county 9 9,9 9,9 7 5,2 4,6 4,5 5,2 Vejle county 9,2 10,7 11,3 7,6 6 4,8 4,9 6,1 Ringkøbing county 7,7 8,4 8,8 6,4 4,8 4,1 4,1 5,3 Århus county 10,5 12 12,8 9,3 7,2 6,2 6 7,1 Viborg county 8,6 9,5 9,6 7,2 5,1 4,6 4,3 4,9 Northern Jutland county 12,9 14,5 15,1 10,7 8,1 7,2 6,8 8,7 Source: www.statistikbanken.dk However, the unemployment rates and their evolution over time di¤er be- tween Danish counties, see Table 1. -

Juleture 2020 Fyn - Sjælland Afg Mod Sjælland Ca

Juleture 2020 Fyn - Sjælland Afg mod Sjælland ca. kl. 10:00 Svendborg Odense Nyborg ↔ København Afg mod fyn ca. kl.15:00 kr. 150 Afg mod Sjælland ca. kl. 10:00 Svendborg Odense Nyborg ↔ Roskilde Hillerød Helsingør Afg mod fyn ca. kl.15:00 kr. 150 Afg mod Sjælland ca. kl. 10:00 Svendborg Odense Nyborg ↔ Næstved Vordingborg Nykøbing F Afg mod fyn ca. kl.15:00 kr. 150 Afg mod Sjælland ca. kl. 10:00 Svendborg Odense Nyborg ↔ Korsør Slagelse Sorø Ringsted Køge Afg mod fyn ca. kl.15:00 kr. 150 Jylland - Fyn Afg mod Fyn ca. kl. 10:00 Aalborg Hobro Randers ↔ Middelfart Odense Svendborg Afg mod Jylland ca. kl.15:00 kr. 200 Afg mod Fyn ca. kl. 10:00 Aarhus ↔ Middelfart Odense Svendborg Afg mod Jylland ca. kl.15:00 kr. 150 Afg mod Fyn ca. kl. 10:00 Viborg Silkeborg ↔ Middelfart Odense Svendborg Afg mod Jylland ca. kl.15:00 kr. 150 Afg mod Fyn ca. kl. 10:00 Holstebro Herning ↔ Middelfart Odense Svendborg Afg mod Jylland ca. kl.15:00 kr. 150 Afg mod Fyn ca. kl. 10:00 Esbjerg Kolding Fredericia ↔ Middelfart Odense Svendborg Afg mod Jylland ca. kl.15:00 kr. 150 Afg mod Fyn ca. kl. 10:00 Skanderborg Horsens Vejle ↔ Middelfart Odense Svendborg Afg mod Jylland ca. kl.15:00 kr. 150 Afg mod Fyn ca. kl. 10:00 Sønderborg Aabenraa Haderslev ↔ Middelfart Odense Svendborg Afg mod Jylland ca. kl.15:00 kr. 150 Jylland - Sjælland Afg mod Sjælland ca. kl. 10:00 Aalborg Hobro Randers ↔ København Afg mod Jylland ca. -

Fortid Og Nutid 1960. 21.Bd. 1.Hf

Dette værk er downloadet fra Slægtsforskernes Bibliotek SLÆGTSFORSKERNES BIBLIOTEK Slægtsforskernes Bibliotek drives af foreningen Danske Slægtsforskere. Det er et special-bibliotek med værker, der er en del af vores fælles kulturarv, blandt andet omfattende slægts-, lokal- og personalhistorie. Slægtsforskernes Bibliotek: http://bibliotek.dis-danmark.dk Foreningen Danske Slægtsforskere: www.slaegtogdata.dk Bemærk, at biblioteket indeholder værker både med og uden ophavsret. Når det drejer sig om ældre værker, hvor ophavsretten er udløbet, kan du frit downloade og anvende PDF-filen. Drejer det sig om værker, som er omfattet af ophavsret, skal du være opmærksom på, at PDF- filen kun er til rent personlig brug. TIDSSKRIFT FOR KULTURHISTORIE OG LOKALHISTORIE UDGIVET AF DANSK HISTORISK FÆLLESFORENING FORTID ogNUTID BIND XXI . HEFTE 1 . SIDE 1 — 112 . KØBENHAVN 1960 Statens Arkiv for Historiske Film og Stemmer Af D. Yde-Andersen Statens Arkiv går tilbage til 1911. I dette år blev det norske dagblad Ver dens Gang og den danske filmkonge Ole Olsen dybt uenige. Verdens Gang henvendte sig til Politiken om kollegial støtte, og Henrik Cavling over drog det til sin unge medarbejder Anker Kirkeby at udføre eksekutionen. Anker Kirkeby var en journalist af format. Han så, at der kunne komme noget nyttigt ud af striden. Der var tid efter anden fremkommet med delelser om, at man i udlandet ville oprette arkiver indeholdende film, der skildrede store begivenheder eller kendte personer, til brug for histo rieforskningen. Nu mente Anker Kirkeby, der var mulighed for at få op rettet et sådant arkiv herhjemme. Han gik til Ole Olsen og tilbød at skaffe ham fred med Verdens Gang, mod at Ole Olsens selskab, Nordisk Films Kompagni, optog en række »kinematografiske Portrætter af kendte Per sonligheder, som det maa være af historisk Interesse at faa overleveret Efterverdenen«. -

To Fynske Herregårde Under Louis Seize-Tiden: Krengerup Og Einsidelsborg

Fynske Årbøger 1975 To fynske herregårde under Louis Seize-tiden: Krengerup og Einsidelsborg Af Claus M. Smidt Ved skæbnens gunst er vor Louis Seize-arkitektur i provinsen for trinsvis blevet præget af elever af arkitekten N.-H. Jardin. En 1 særlig rig del af denne er - som godtgjort af Chr. Elling ) - den fynske. Et af de mest imponerende herregårdsanlæg fra denne tid er Krengerup på Fyn. Over hoveddøren står indskriften "Af Fried rich Siegfried Baron af Rantzau Ridder, kammerherre og oberst og hans frue Sophie Magdalena født Baronesse Juell-Wind er dette hus opbygget 1772". Elling har påvist, at indskriften mere er et fingerpeg end en eksakt oplysning, der står til troende. Nævnte år var Rantzau hverken ridder, kammerherre, oberst eller ægtemand. Først 1776 opfyldte han dette, hvorfor den indi rekte tale er: begyndt 1772 og fuldendt omkring 1776 eller der efter. Om bygningens arkitekt ved samtiden intet at sige. Et kunst 2 nerleksikon fra 1829 angiver dog denne som Hans Næss. ) Næss var født på Fyn 1723 som søn af bønder fra Assens-eg nen.3) Som ung kom han på godskontoret på Brahesborg hos grev Chr. Rantzau. Derpå gik vejen til amtsstuen i Assens. I 1758 foretog han det store spring til København. Rantzau havde anbefa let ham til grev Otto Thott, der skaffede ham en volontørplads i Rentekammeret Samtidig hermed begyndte han på Kunstakade miet. Efter at have gennemgået arkitekturskolen og have fået alle dennes medaljer, inclusive den store guldmedalje, blev Næss 1765 informator i bygningskunsten og forlod derfor Rentekam- Fynske Årbøger 1975 To fynske hen·egårde under Louis Seize-tiden 73 meret. -

Grade a Logistics Space Available to Lease

Grade A logistics space available to lease Units from 5,000 sq m - 26,000 sq m www.iparkcopenhagen.com Flexible logistics space north of Copenhagen Verdion iPark Copenhagen is the Located in Allerød Kommune, the site is within 25 minutes of central Copenhagen as only zoned and developable land well as being close to Northern Zealand’s north of Copenhagen capable of pharmaceutical sector and other industries. delivering warehouse buildings New occupiers at Verdion iPark Copenhagen of over 5,000 sq m. will join DHL, which has taken a new 12,000 sq m state-of-the-art facility to support its contract with one of the world’s largest healthcare companies. The site is zoned for logistics and industrial use, and the infrastructure to support development is already in place. 26,000 sq m available for new logistics space adjacent to DHL’s facility in Allerød DHL’s facility at Verdion iPark Copenhagen Why Allerød? • Fast journey time (25 mins) to central Copenhagen UNEEG medical A / S • Good public transport connections Vassingerødvej and strong local workforce • Low tax and occupational costs • Nearby occupiers: DHL, Widex, Missionpharma, Cederroth, Gosh Farremosen Cosmetics, Fritz Hansen and Reconor Bus Stop DHL Project Highlights • 26,000 sq m of modern warehouse and ancillary office space • Unit sizes from 5,000 sq m • Located directly on Highway 16, Junction 11 Allerød S Nymøllevej • Road infrastructure, utilities and zoning in place • Highly specified energy efficient design as standard • Flexible building layout and specification options • -

Kommunale Arbejdspladser Udtaget Til Strejke

Kommunale arbejdspladser udtaget til strejke I denne oversigt finder du de kommunale arbejdspladser, hvor Dansk Sygeplejeråd har udtaget sine medlemmer til strejke. Hvis du er omfattet, får du direkte besked. Oversigten er fordelt på DSR’s fem kredse i alfabetisk rækkefølge: KREDS HOVEDSTADEN ....................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 2 KREDS MIDTJYLLAND ......................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 6 KREDS NORDJYLLAND ...................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 12 KREDS SJÆLLAND ............................................................................................................................................................................................................................. 15 KREDS SYDDANMARK ...................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 19 1 KREDS HOVEDSTADEN Frederiksberg Kommune Hjemmeplejen Område 10 Finsensvej 80 B, St 2000 Frederiksberg -

Rail Net Denmark

Banedanmark Procurement, tenders, and upcoming projects in Banedanmark Senior Market Research Analyst Cathrine Carøe at Building Network Construction Conference 2017.10.04 1 Facts about Banedanmark A state-owned enterprise under the Ministry of Economy Transport, Building, and Housing 8.5 Appropriations Billion DKK 3476 3000 196 mio. 1.3 Billion Technical DKK Division Passengers Km track Daily trains per year Construction 4.3 Billion Division DKK 8 mio. 2.235 92,6% ton 1.4 Billion Renewal Freight Punctuality DKK per year Employees at S-banen 2 Current 4 major projects are in progress New landscape of railway infrastructure in Denmark – New Line Copenhagen – Ringsted – New railway Fehmarn Belt – Electrification Programme – Signalling Programme 3 Construction Division Construction Division is responsible for planning, managing and implementing projects. – Renewal of tracks, bridges, stations, sleepers, drainage, ballast. – Derived works regarding catenary, interlocking and ATC. Find upcoming tenders at: https://banedktenderplan.tricommerce.dk/#/list/incoming 4 Projects 2019 East and West 5 #467 Track renewal Høje Tåstrup-Roskilde Station Budget: +250 M DKK. – 10 km track renewall per track (= 40 km). – Drainage. – 12 switches. – Station with works: Høje Tåstrup – Derived works, interlocking, and adjustment of catenary system. 6 #468 Track renewal Ringsted-Korsør Budget: +600 M DKK. – 22 km new track – 36 km new sleepers – 51 km ballast cleaning – 32 km new sub layer – 33 new switches – 23 removal of switches – New track layout – 3 km drainage – Track lowering on 8 different locations – Earth issues at Tjæreby and Forlev – Interlocking and catenary works due to track renewal 7 Track renewal Fyn Budget: – 22 km renewal of sleepers – 39 km ballast cleaning.