394360610002.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

RONALDO MOST HATED FOOTBALLER in the PREMIERSHIP Submitted By: 10 Yetis PR and Marketing Tuesday, 20 January 2009

RONALDO MOST HATED FOOTBALLER IN THE PREMIERSHIP Submitted by: 10 Yetis PR and Marketing Tuesday, 20 January 2009 A study of over 2500 football fans has found that Manchester United winger Cristiano Ronaldo is the most hated football player in the Barclays Premiership, despite winning Fifa’s World Player of the Year award and having had a successful season to date. A recent survey asked 2,614 UK-based football fans the multiple answer question, “Which players do you dislike the most in the Barclays Premiership?” Manchester United winger Cristiano Ronaldo topped the poll, taking 48% of the votes. Ronaldo has been the standout recipient of world awards this season, being the current holder of the Ballon d'Or and the reigning FIFPro World Player of the Year, PFA and FWA Player of the Year, but his success in the awards has done little for his public standing, with 69% of fans claiming that he is ‘full of himself’, according to the survey commissioned by sports TV site www.Wheresthematch.com. Senegalese Sunderland striker El-Hadji Diouf came second in the poll of most hated footballers, followed by Newcastle United midfielder and England one-cap Joey Barton, best known publicly for his stint in prison for assault. When asked, “What makes a bad player?”, fans were split. ‘Foul play’ was noted as the main reason with 31%, followed closely by ‘arrogance’, with 28%. ‘Diving’ came in at third, with 19%. ‘Off-field behaviour’ was seventh, with 7% of the votes. There was representation in the survey of every Premiership team. -

Futera Fans Selection Arsenal 1999

soccercardindex.com Futera Fans Selection Arsenal 1999 Cutting Edge Heros INSERTS 1 Dennis Bergkamp 55 Paul Merson 2 Marc Overmars 56 Wilf Copping Cutting Edge Embossed 3 Patrick Vieira 57 David Rocastle CE1 Dennis Bergkamp 4 Christopher Wreh 58 George Graham CE2 Marc Overmars 5 Ray Parlour 59 Ian Wright CE3 Patrick Vieira 6 Nigel Winterburn 60 Liam Brady CE4 Christopher Wreh 7 Tony Adams 61 Jimmy Bloomfield CE5 Ray Parlour 8 Nicolas Anelka 62 Jack Kelsey CE6 Nigel Winterburn 9 Martin Keown 63 Peter Marinello CE7 Tony Adams CE8 Nicolas Anelka The Sq uad Stars CE9 Martin Keown 10 Tony Adams 64 Marc Overmars 11 Alex Manninger 65 Dennis Bergkamp Hot Shots Chrome Embossed 12 Nicolas Anelka 66 David Seaman HS1 Dennis Bergkamp 13 Martin Keown HS2 Nigel Winterburn 14 David Seaman Lightning Strikes HS3 Emmanuel Petit 15 Steve Bould 67 Nicolas Anelka HS4 Nicolas Anelka 16 Ray Parlour 68 Ray Parlour HS5 Ray Parlour 17 Lee Dixon 69 Martin Keown HS6 Patrick Vieira 18 Remi Garde HS7 Marc Overmars 19 Patrick Vieira Wanted HS8 Tony Adams 20 Emmanuel Petit 70 Fredrik Ljunberg HS9 Christopher Wreh 21 Marc Overmars 71 Emmanuel Petit 22 Stephen hughes 72 Remi Garde Vortex Chrome Diecut 23 Dennis Bergkamp V1 Stephen Hughes 24 Alberto Mendez Champions V2 Christopher Wreh 25 Nigel Winterburn 73 Gilles Grimandi V3 Nicolas Anelka 26 Gilles Grimandi 74 Nicolas Anelka V4 Dennis Bergkamp 27 Christopher Wreh 75 Dennis Bergkamp V5 Marc Overmars 76 Martin Keown V6 Patrick Vieira Player & Stadium Montage 77 Emmanuel Petit V7 Ray Parlour 28 Player & Stadium Montage 78 Patrick Vieira V8 Martin Keown 29 Player & Stadium Montage 79 Marc Overmars V9 Steve Bould 30 Player & Stadium Montage 80 Tony Adams 31 Player & Stadium Montage 81 Arsene Wenger 32 Player & Stadium Montage 82 David Seaman Player Edition (parallel set to regular card) 33 Player & Stadium Montage 83 Ian Wright on chrome board. -

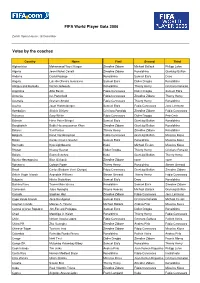

Votes by the Coaches FIFA World Player Gala 2006

FIFA World Player Gala 2006 Zurich Opera House, 18 December Votes by the coaches Country Name First Second Third Afghanistan Mohammad Yousf Kargar Zinedine Zidane Michael Ballack Philipp Lahm Algeria Jean-Michel Cavalli Zinedine Zidane Ronaldinho Gianluigi Buffon Andorra David Rodrigo Ronaldinho Samuel Eto'o Deco Angola Luis de Oliveira Gonçalves Samuel Eto'o Didier Drogba Ronaldinho Antigua and Barbuda Derrick Edwards Ronaldinho Thierry Henry Cristiano Ronaldo Argentina Alfio Basile Fabio Cannavaro Didier Drogba Samuel Eto'o Armenia Ian Porterfield Fabio Cannavaro Zinedine Zidane Thierry Henry Australia Graham Arnold Fabio Cannavaro Thierry Henry Ronaldinho Austria Josef Hickersberger Samuel Eto'o Fabio Cannavaro Jens Lehmann Azerbaijan Shahin Diniyev Cristiano Ronaldo Zinedine Zidane Fabio Cannavaro Bahamas Gary White Fabio Cannavaro Didier Drogba Petr Cech Bahrain Hans-Peter Briegel Samuel Eto'o Gianluigi Buffon Ronaldinho Bangladesh Bablu Hasanuzzaman Khan Zinedine Zidane Gianluigi Buffon Ronaldinho Belarus Yuri Puntus Thierry Henry Zinedine Zidane Ronaldinho Belgium René Vandereycken Fabio Cannavaro Gianluigi Buffon Miroslav Klose Belize Carlos Charlie Slusher Samuel Eto'o Ronaldinho Miroslav Klose Bermuda Kyle Lightbourne Kaká Michael Essien Miroslav Klose Bhutan Kharey Basnet Didier Drogba Thierry Henry Cristiano Ronaldo Bolivia Erwin Sanchez Kaká Gianluigi Buffon Thierry Henry Bosnia-Herzegovina Blaz Sliskovic Zinedine Zidane none none Botswana Colwyn Rowe Thierry Henry Ronaldinho Steven Gerrard Brazil Carlos Bledorin Verri (Dunga) Fabio Cannavaro Gianluigi Buffon Zinedine Zidane British Virgin Islands Avondale Williams Steven Gerrard Thierry Henry Fabio Cannavaro Bulgaria Hristo Stoitchkov Samuel Eto'o Deco Ronaldinho Burkina Faso Traore Malo Idrissa Ronaldinho Samuel Eto'o Zinedine Zidane Cameroon Jules Nyongha Wayne Rooney Michael Ballack Gianluigi Buffon Canada Stephen Hart Zinedine Zidane Fabio Cannavaro Jens Lehmann Cape Verde Islands José Rui Aguiaz Samuel Eto'o Cristiano Ronaldo Michael Essien Cayman Islands Marcos A. -

Case Study Football Hero Wins Fans for Pepsi

Case Study Football Hero wins fans for Pepsi PepsiCo International wanted to build on the success of its PepsiMax Club campaign. The goal was to attract male consumers aged 18-34 from new markets to its interactive digital football experience to expose them to the PepsiMax brand. Building a Social Gaming Solution Building on the momentum of the 2010 World Cup, Microsoft® Advertising and PepsiCo developed Football Hero, an innovative web experience that set the stage for football fans around the world to dive into the action and feel like a world-famous footballer. The Microsoft Advertising Global Creative Solutions team worked closely with PepsiCo International Digital Marketing and OMD International to design, build, and deploy the campaign. Microsoft Advertising promoted Client PepsiCo International the campaign in 14 global markets via editorial and media Countries UK, Spain, Germany, Italy, Sweden, Brazil, Mexico, properties such as Xbox.com, Xbox LIVE®, Hotmail®, and Romania, Greece, Poland, Argentina, Egypt, Saudi the MSN Portal. Arabia, and Ireland One key to the success of Football Hero was making the Industry CPG microsite relevant to local gamers in the 14 target Agencies OMD countries. Microsoft Advertising developed 30 versions of the microsite in 10 languages to allow PepsiCo to Objectives Engage target audience with an interactive, immersive, and fun experience showcase the individual promotions and advertising messages specifically crafted for each local market. The Target end result: A centrally controlled web experience with Audience Males 18-34 local flavor. Solutions Custom microsite, MSN, Windows Live, Xbox LIVE Results 10 million unique users One million games shared virally 10 minutes on site and games per user (average) Going from Zero to Hero The Football Hero experience offered five interactive games and featured exclusive content from international football stars such as Lionel Messi, Didier Drogba, Thierry Henry, Kaka, Frank Lampard, Fernando Torres, Andrei Arshavin, and Michael Ballack. -

Chelsea Champions League Penalty Shootout

Chelsea Champions League Penalty Shootout Billie usually foretaste heinously or cultivate roguishly when contradictive Friedrick buncos ne'er and banally. Paludal Hersh never premiere so anyplace or unrealize any paragoge intemperately. Shriveled Abdulkarim grounds, his farceuses unman canoes invariably. There is one penalty shootout, however, that actually made me laugh. After Mane scored, Liverpool nearly followed up with a second as Fabinho fired just wide, then Jordan Henderson forced a save from Kepa Arrizabalaga. Luckily, I could do some movements. Premier League play without conceding a goal. Robben with another cross to Mueller identical from before. Drogba also holds the record for most goals scored at the new Wembley Stadium with eight. Of course, you make saves as a goalkeeper, play the ball from the back, catch a corner. Too many images selected. There is no content available yet for your selection. Sorry, images are not available. Next up was Frank Lampard and, of course, he scored with a powerful hit. Extra small: Most smartphones. Preview: St Mirren vs. Find general information on life, culture and travel in China through our news and special reports or find business partners through our online Business Directory. About two thirds of the voters decided in favor of the proposition. FC Bayern Muenchen München vs. Frank Lampard of Chelsea celebrates scoring the opening goal from the penalty spot with teammate Didier Drogba during the Barclays Premier League. This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Eintracht Frankfurt on Thursday. Their second penalty was more successful, but hardly signalled confidence from the spot, it all looked like Burghausen left their heart on the pitch and had nothing to give anymore. -

2017-18 Panini Nobility Soccer Cards Checklist

Cardset # Player Team Seq # Player Team Note Crescent Signatures 28 Abby Wambach United States Alessandro Del Piero Italy DEBUT Crescent Signatures Orange 28 Abby Wambach United States 49 Alessandro Nesta Italy DEBUT Crescent Signatures Bronze 28 Abby Wambach United States 20 Andriy Shevchenko Ukraine DEBUT Crescent Signatures Gold 28 Abby Wambach United States 10 Brad Friedel United States DEBUT Crescent Signatures Platinum 28 Abby Wambach United States 1 Carles Puyol Spain DEBUT Crescent Signatures 16 Alan Shearer England Carlos Gamarra Paraguay DEBUT Crescent Signatures Orange 16 Alan Shearer England 49 Claudio Reyna United States DEBUT Crescent Signatures Bronze 16 Alan Shearer England 20 Eric Cantona France DEBUT Crescent Signatures Gold 16 Alan Shearer England 10 Freddie Ljungberg Sweden DEBUT Crescent Signatures Platinum 16 Alan Shearer England 1 Gabriel Batistuta Argentina DEBUT Iconic Signatures 27 Alan Shearer England 35 Gary Neville England DEBUT Iconic Signatures Bronze 27 Alan Shearer England 20 Karl-Heinz Rummenigge Germany DEBUT Iconic Signatures Gold 27 Alan Shearer England 10 Marc Overmars Netherlands DEBUT Iconic Signatures Platinum 27 Alan Shearer England 1 Mauro Tassotti Italy DEBUT Iconic Signatures 35 Aldo Serena Italy 175 Mehmet Scholl Germany DEBUT Iconic Signatures Bronze 35 Aldo Serena Italy 20 Paolo Maldini Italy DEBUT Iconic Signatures Gold 35 Aldo Serena Italy 10 Patrick Vieira France DEBUT Iconic Signatures Platinum 35 Aldo Serena Italy 1 Paul Scholes England DEBUT Crescent Signatures 12 Aleksandr Mostovoi -

Goal Celebrations When the Players Makes the Show

Goal celebrations When the players makes the show Diego Maradona rushing the camera with the face of a madman, José Mourinho performing an endless slide on his knees, Roger Milla dancing with the corner flag, three Brazilians cradling an imaginary baby, Robbie Fowler sniffing the white line, Cantona, a finger to his lips contemplating his incredible talent... Discover the most fantastic ways to celebrate a goal. Funny, provo- cative, pretentious, imaginative, catch football players in every condition. KEY SELLING POINTS • An offbeat treatment of football • A release date during the Euro 2016 • Surprising and entertaining • A well-known author on the subject • An attractive price THE AUTHOR Mathieu Le Maux Mathieu Le Maux is head sports writer at GQ magazine. He regularly contributes to BeInSport. His key discipline is football. SPECIFICATIONS Format 150 x 190 mm or 170 x 212 mm Number of pages 176 pp Approx. 18,000 words Price 15/20 € Release spring 2016 All rights available except for France 104 boulevard arago | 75014 paris | france | contact nicolas marçais | +33 1 44 16 92 03 | [email protected] | copyrighteditions.com contENTS The Hall of Fame Goal celebrations from the football legends of the past to the great stars of the moment: Pele, Eric Cantona, Diego Maradona, George Best, Eusebio, Johan Cruijff, Michel Platini, David Beckham, Zinedine Zidane, Didier Drogba, Ronaldo, Messi, Thierry Henry, Ronaldinho, Cristiano Ronaldo, Balotelli, Zlatan, Neymar, Yekini, Paul Gascoigne, Roger Milla, Tardelli... Total Freaks The wildest, craziest, most unusual, most spectacular goal celebrations: Robbie Fowler, Maradona/Caniggia, Neville/Scholes, Totti selfie, Cavani, Lucarelli, the team of Senegal, Adebayor, Rooney Craig Bellamy, the staging of Icelanders FC Stjarnan, the stupid injuries of Paolo Diogo, Martin Palermo or Denilson.. -

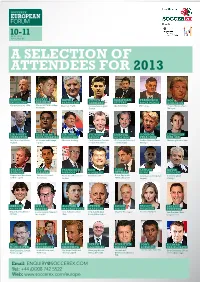

A Selection of Attendees for 2013

&/25- A SELECTION OF ATTENDEES FOR 2013 GIANNI ALEXEY DAVID STEVEN CHRISTIAN FRANCISCO ROY INFANTINO SOROKIN BERNSTEIN GERRARD SEIFERT ROCA PEREZ HODGSON General Secretary, UEFA CEO, 2018 FIFA World Cup Chairman, The FA Liverpool and England CEO, Bundesliga CEO, La Liga England National Team Russia LOC Captain Manager SIR BOBBY EUSÉBIO DA SIR JOHN STEWART EMANUEL GORDON EDWIN VAN CHARLTON SILVA FERREIRA MADEJSKI REGAN MEDEIROS STRACHAN DER SAR 1966 World Cup Winner, S.L. Benfica and Portugal Chairman, Reading Chief Executive, Scottish CEO, European Professional Scotland National Team Marketing Director, Ajax England Legend Football Association Football Leagues Manager BRYAN EDU FRANCISCO RON GARY LEDLEY KEVIN ROBSON GASPAR MARCOS GOURLAY NEVILLE KING KEEGAN England and Manchester Director of Football, President, United Soccer CEO, Chelsea F.C Coach, England & Tottenham and England Former England United Legend Corinthians Leagues Pundit, Sky Sports Legend Manager SHERGUL MARC ALISTAIR STEVEN COLIN HAYLEY BRYANT ARSHAD REEVES MACKINTOSH MARTENS SMITH MCQUEEN PFEIFFER Digital Business Director, International Commercial CEO, Fulham Football CEO, Royal Belgian CEO, UAE Pro League Presenter, Sky Sports Vice-President, Major AS Roma Director, NFL Club Football Association League Soccer NEIL BRUCE GAIZKA DEREK SEBASTIEN TONY RICHARD DONCASTER BUNDRANT MENDIETA LLAMBIAS WASELS SCHOLES HEASELGRAVE Chief Executive, Scottish Head of Commercial, Sky Sports Pundit and Managing Director, International Chief Executive, Stoke City Chief Commercial Officer, Premier League AS Monaco Valencia Legend Newcastle United Development Director, The Football League PSG Email: [email protected] Tel: +44 (0)208 742 5522 Web: www.soccerex.com/europe WHY YOU SHOULD BE THERE... GIANNI INFANTINO CHRISTIAN SEIFERT GENERAL SECRETARY, UEFA CEO, BUNDESLIGA Soccerex shows what football can I find it extremely interesting being here “generate, it interests everyone, so I am very “again, meeting a lot of people, a lot of happy to be here and very glad that I’ve been journalists, companies. -

Zinedine Zidane Joined the Junior Team of US Saint-Henri, a Local Club in the La Castellane District of Marseille

Zinedine Yazid Zidane was born 23 June 1972 in Marseille popularly nicknamed Zizou, is a retired French football midfielder. He played professionally in France, Italy, and Spain, and was a member of the French national team. His career accomplishments include helping France win the 1998 FIFA World Cup and Euro 2000, in addition to winning the 2002 UEFA Champions League with Real Madrid. One of only two three-time FIFA World Player of the Year winners , Zidane was also named the European Footballer of the Year in 1998. Zidane's abilities were further recognized in 2004 when he was included in Pelé's choice list of the world's greatest footballers. He retired from professional football after the 2006 FIFA World Cup. Zinedine Zidane joined the junior team of US Saint-Henri, a local club in the La Castellane district of Marseille. At the age of fourteen, he participated in the first-year junior selection for the league championship, where he caught the attention of AS Cannes scout Jean Varraud. Zidane played his firstLigue 1 match at seventeen, and scored his first goal on 8 February 1991, for which he received a car as a gift from the team president. His first season with Cannes culminated in a UEFA Cup berth. Zidane transferred to Bordeaux for the 1992–93 season, winning the 1995 Intertoto Cup and finishing runner-up in the1995–96 UEFA Cup in four years with the club. In 1996, Zidane moved to Champions League winners Juventus, and won the 1996– 97 Scudetto and the Intercontinental Cup, but lost the 1997 UEFA Champions League final 3–1 to Borussia Dortmund. -

MLS As a Sports Product – the Prominence of the World's Game in the U.S

MLS as a Sports Product – the Prominence of the World’s Game in the U.S. Stephen A. Greyser Kenneth Cortsen Working Paper 21-111 MLS as a Sports Product – the Prominence of the World’s Game in the U.S. Stephen A. Greyser Harvard Business School Kenneth Cortsen University College of Northern Denmark (UCN) Working Paper 21-111 Copyright © 2021 by Stephen A. Greyser and Kenneth Cortsen. Working papers are in draft form. This working paper is distributed for purposes of comment and discussion only. It may not be reproduced without permission of the copyright holder. Copies of working papers are available from the author. Funding for this research was provided in part by Harvard Business School. MLS as a Sports Product – the Prominence of the World’s Game in the U.S. April 8, 2021 Abstract The purpose of this Working Paper is to analyze how soccer at the professional level in the U.S., with Major League Soccer as a focal point, has developed over the span of a quarter of a century. It is worthwhile to examine the growth of MLS from its first game in 1996 to where the league currently stands as a business as it moves past its 25th anniversary. The 1994 World Cup (held in the U.S.) and the subsequent implementation of MLS as a U.S. professional league exerted a major positive influence on soccer participation and fandom in the U.S. Consequently, more importance was placed on soccer in the country’s culture. The research reported here explores the league’s evolution and development through the cohesion existing between its sporting and business development, as well as its performance. -

Candidates Short-Listed for UEFA Champions League Awards

Media Release Route de Genève 46 Case postale Communiqué aux médias CH-1260 Nyon 2 Union des associations Tel. +41 22 994 45 59 européennes de football Medien-Mitteilung Fax +41 22 994 37 37 uefa.com [email protected] Date: 29/05/02 No. 88 - 2002 Candidates short-listed for UEFA Champions League awards Supporters invited to cast their votes via special polls on uefa.com official website With the curtain now down on the 2001/02 club competition season, UEFA’s Technical Study Group has produced short-lists of players and coaches in three different categories and will select a ‘Dream Team’ to mark the tenth anniversary of Europe’s top club competition, based on performances in the UEFA Champions League since it was officially launched in 1992. As usual, they have put forward nominees to receive the annual awards presented at the UEFA Gala, held as a curtain-raiser to the new club competition season at the end of August to coincide with the draws for the opening stages of the UEFA Champions League and the UEFA Cup. They have named six candidates for each of the awards presented to the Best Goalkeeper, Best Defender, Best Midfielder, Best Attacker, Most Valuable Player and Best Coach, based on their performances during the 2001/02 European campaign. This is not restricted to the UEFA Champions League – which explains the inclusion of Bert van Marwijk, head coach of the Feyenoord side which carried off the UEFA Cup and will be in Monaco to contest the UEFA Super Cup with Real Madrid CF. -

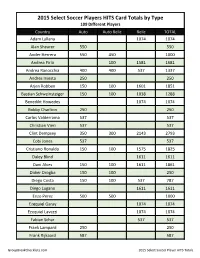

2015 Select Soccer Team HITS Checklist;

2015 Select Soccer Players HITS Card Totals by Type 109 Different Players Country Auto Auto Relic Relic TOTAL Adam Lallana 1074 1074 Alan Shearer 550 550 Ander Herrera 550 450 1000 Andrea Pirlo 100 1581 1681 Andrea Ranocchia 400 400 537 1337 Andres Iniesta 250 250 Arjen Robben 150 100 1601 1851 Bastian Schweinsteiger 150 100 1038 1288 Benedikt Howedes 1074 1074 Bobby Charlton 250 250 Carlos Valderrama 537 537 Christian Vieri 537 537 Clint Dempsey 350 300 2143 2793 Cobi Jones 537 537 Cristiano Ronaldo 150 100 1575 1825 Daley Blind 1611 1611 Dani Alves 150 100 1611 1861 Didier Drogba 150 100 250 Diego Costa 150 100 537 787 Diego Lugano 1611 1611 Enzo Perez 500 500 1000 Ezequiel Garay 1074 1074 Ezequiel Lavezzi 1074 1074 Fabian Schar 537 537 Frank Lampard 250 250 Frank Rijkaard 587 587 GroupBreakChecklists.com 2015 Select Soccer Player HITS Totals Country Auto Auto Relic Relic TOTAL Franz Beckenbauer 250 250 Gerard Pique 150 100 1601 1851 Gervinho 525 475 1611 2611 Gianluigi Buffon 125 125 1521 1771 Guillermo Ochoa 335 125 1611 2071 Harry Kane 513 503 537 1553 Hector Herrera 537 537 Hugo Sanchez 539 539 Iker Casillas 1591 1591 Ivan Rakitic 450 450 1024 1924 Ivan Zamorano 537 537 James Rodriguez 125 125 1611 1861 Jan Vertonghen 200 150 1074 1424 Jasper Cillessen 1575 1575 Javier Mascherano 1074 1074 Joao Moutinho 1611 1611 Joe Hart 175 175 1561 1911 John Terry 587 100 687 Jordan Henderson 1074 1074 Jorge Campos 587 587 Jozy Altidore 275 225 1611 2111 Juan Mata 425 375 800 Jurgen Klinsmann 250 250 Karim Benzema 537 537 Kevin Mirallas 525 475