Download This PDF File

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Qatar's Water Supply to Reach 480M Gallons

3rd Best News Website in the Middle East BUSINESS | 17 SPORT | 24 UK’s May sets out I’ll probably race for vision for frictionless the next two years, trade after Brexit says Rossi Saturday 3 March 2018 | 15 Jumada II I 1439 www.thepeninsula.qa Volume 22 | Number 7454 | 2 Riyals Freedom to roam with Bill Protection! Terms & conditions apply Sheikha Moza meets Arab World Institute President Emir holds phone Qatar’s water talks with Burkina Faso President supply to reach DOHA: Emir H H Sheikh Tamim bin Hamad Al Thani held yesterday via telephone a conversation with the Pres- 480m gallons ident of Brukina Faso, Roch Marc Christian Kabore, to THE PENINSULA The project is offer condolences on the expected to provide victims of attacks that DOHA: Qatar’s water targeted army headquarters, production capacity increased after the completion the French Embassy and The by 15 percent in 2017 with the of all phases by Institute Francais in the opening of phase one of the second half 2018, a capital Ouagadougou, Integrated Water and Power total of 136 million wishing the injured a speedy Project (IWPP) in Umm Al Houl, recovery. The Emir expressed Qatar General Electricity and gallons of water his condemnation to the Water Corporation (Kahramaa) raising the total heinous crime, stressing the said in a statement issued on water production State of Qatar’s support of the occasion of Arab Water Day. Burkina Faso in the face of “The project is expected to in the country to extremism and terrorism of provide after the completion of about 480 million all kinds. -

List of Empanelled Artist

INDIAN COUNCIL FOR CULTURAL RELATIONS EMPANELMENT ARTISTS S.No. Name of Artist/Group State Date of Genre Contact Details Year of Current Last Cooling off Social Media Presence Birth Empanelment Category/ Sponsorsred Over Level by ICCR Yes/No 1 Ananda Shankar Jayant Telangana 27-09-1961 Bharatanatyam Tel: +91-40-23548384 2007 Outstanding Yes https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vwH8YJH4iVY Cell: +91-9848016039 September 2004- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Vrts4yX0NOQ [email protected] San Jose, Panama, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YDwKHb4F4tk [email protected] Tegucigalpa, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SIh4lOqFa7o Guatemala City, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MiOhl5brqYc Quito & Argentina https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=COv7medCkW8 2 Bali Vyjayantimala Tamilnadu 13-08-1936 Bharatanatyam Tel: +91-44-24993433 Outstanding No Yes https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wbT7vkbpkx4 +91-44-24992667 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zKvILzX5mX4 [email protected] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kyQAisJKlVs https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=q6S7GLiZtYQ https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WBPKiWdEtHI 3 Sucheta Bhide Maharashtra 06-12-1948 Bharatanatyam Cell: +91-8605953615 Outstanding 24 June – 18 July, Yes https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WTj_D-q-oGM suchetachapekar@hotmail 2015 Brazil (TG) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UOhzx_npilY .com https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SgXsRIOFIQ0 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lSepFLNVelI 4 C.V.Chandershekar Tamilnadu 12-05-1935 Bharatanatyam Tel: +91-44- 24522797 1998 Outstanding 13 – 17 July 2017- No https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ec4OrzIwnWQ -

Masculinity and the Structuring of the Public Domain in Kerala: a History of the Contemporary

MASCULINITY AND THE STRUCTURING OF THE PUBLIC DOMAIN IN KERALA: A HISTORY OF THE CONTEMPORARY Ph. D. Thesis submitted to MANIPAL ACADEMY OF HIGHER EDUCATION (MAHE – Deemed University) RATHEESH RADHAKRISHNAN CENTRE FOR THE STUDY OF CULTURE AND SOCIETY (Affiliated to MAHE- Deemed University) BANGALORE- 560011 JULY 2006 To my parents KM Rajalakshmy and M Radhakrishnan For the spirit of reason and freedom I was introduced to… This work is dedicated…. The object was to learn to what extent the effort to think one’s own history can free thought from what it silently thinks, so enable it to think differently. Michel Foucault. 1985/1990. The Use of Pleasure: The History of Sexuality Vol. II, trans. Robert Hurley. New York: Vintage: 9. … in order to problematise our inherited categories and perspectives on gender meanings, might not men’s experiences of gender – in relation to themselves, their bodies, to socially constructed representations, and to others (men and women) – be a potentially subversive way to begin? […]. Of course the risks are very high, namely, of being misunderstood both by the common sense of the dominant order and by a politically correct feminism. But, then, welcome to the margins! Mary E. John. 2002. “Responses”. From the Margins (February 2002): 247. The peacock has his plumes The cock his comb The lion his mane And the man his moustache. Tell me O Evolution! Is masculinity Only clothes and ornaments That in time becomes the body? PN Gopikrishnan. 2003. “Parayu Parinaamame!” (Tell me O Evolution!). Reprinted in Madiyanmarude Manifesto (Manifesto of the Lazy, 2006). Thrissur: Current Books: 78. -

Vocalese” in the Class of FLE

International Journal of Innovative Technology and Exploring Engineering (IJITEE) ISSN: 2278-3075, Volume-8, Issue- 6S4, April 2019 The Concept of “Vocalese” in the Class of FLE Cynthia George Abstract— “Music is a world within itself a language we all To structure a formative and fun FLE course through understand “– Steve Wonder. According to these words if this the exploitation of a song aiming at functional, language called “Music” can be used in the teaching of a foreign linguistic and socio cultural objectives. language it justifies the words of Plato “Music is a more potent instrument than any other form of education because rhythm and Why use songs? Why music? harmony find their way into the inward places of the soul”. This Music is a therapy. It is just a communication article aims To highlight the advantages of “Vocalese” in the significantly more powerful when compared with words, teaching of French as a foreign langue (FLE) – Francais alot more immediate and much more efficient” – Yehudi Langue Etrangere and to structure a formative and fun FLE Menuhin course through the exploitation of a song aiming at functional, Inclusion of music/ songs into the teaching methodology linguistic and socio cultural objectives. Why use songs? Why is one of the best ways to teach any foreign language music? Music is a therapy. It is a communication far more powerful than words, far more immediate and far more efficient” because – Yehudi Menuhin. Having understood well the advantages of 1. Music creates positive vibes in the class using songs in the teaching of FLE, let us now analyze the 2. -

Take a Sad Song and Make It Better: an Alternative Reading of Anglo-Indian Stereotypes in Shyamaprasad’S Hey Jude (2018)

TAKE A SAD SONG AND MAKE IT BETTER: AN ALTERNATIVE READING OF ANGLO-INDIAN STEREOTYPES IN SHYAMAPRASAD’S HEY JUDE (2018) Glenn D’Cruz ABSTRACT This Paper provides an alternative approach to understanding the function of Anglo- Indian culture in Shyamaprasad’s Malayalam language film Hey Jude (2018). Drawing on his theorization of Anglo-Indian Stereotypes in his book Midnight’s Orphans: Anglo-Indians in Post/Colonial Literature (Peter Lang, 2006), the author contests the reading of the film offered by Rajesh James and Priya Alphonsa Mathew in their recent article, ‘Between Two Worlds: Anglo-Indian Stereotypes and Malayalam Cinema.’ Rather than hastily dismissing representations of Anglo-Indians in Hey Jude as stereotypical and offensive, this critique of James and Mathew’s argument underscores the importance of situating the film in a broader context and paying more detailed attention to the cultural work performed by its themes and tropes. INTRODUCTION FADE IN: INT. Number 13 Charles Street, East London. Early Evening. 1968. A deep red lamp illuminates a framed picture of the Sacred Heart of Jesus. Thick trails of cigarette smoke waft into the frame from below, shrouding the ceremonial lamp in a fog that diminishes its glow. The deep, dulcet tones of Jim Reeves singing ‘Yonder Comes a Sucker’ can be heard over the sound of chatter, laughter, and clinking glasses. IJAIS Vol. 18, No. 2. 2018 pp. 32-47 www.international-journal-of-anglo-indian-studies.org Take a Sad Song and Make it Better 33 DISSOLVE TO: INT: Number 13 Charles Street. Front Room. The Room is populated by a group of young men and women in their late twenties and early thirties. -

Mgl-Int 1-2012-Unpaid Shareholders List As on 31

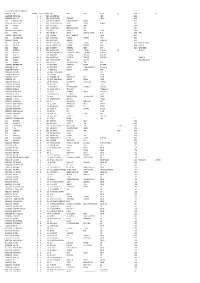

MGL-INT 1-2012-UNPAID SHAREHOLDERS AS ON 31-10-2017 DEMAT ID_FOLIO NAME WARRANT NO MICR DIVIDEND AMOUNT ADDRESS 1 ADDRESS 2 ADDRESS 3 ADDRESS 4 CITY PINCODE JH1 JH2 1202140000080651 SHOBHIT AGARWAL 19 29 25000.00 7/150, SWAROOP NAGAR KANPUR 208002 IN30047642921350 VAGMI KUMAR 21 31 32600.00 214 PANCHRATNA COMPLEX OPP BEDLA ROAD UDAIPUR 313001 001431 JITENDRA DATTA MISRA 22 32 12000.00 BHRATI AJAY TENAMENTS 5 VASTRAL RAOD WADODHAV PO AHMEDABAD 382415 IN30163741220512 DURGA PRASAD MEKA 34 44 10183.00 H NO 4 /60 NARAYANARAO PETA NAGARAM PALVONCHA KHAMMAM 507115 001424 BALARAMAN S N 37 47 20000.00 14 ESOOF LUBBAI ST TRIPLICANE MADRAS 600005 001440 RAJI GOPALAN 59 69 20000.00 ANASWARA KUTTIPURAM THIROOR ROAD KUTTYPURAM KERALA 679571 IN30089610488366 RAKESH P UNNIKRISHNAN 72 82 12250.00 KRISHNA AYYANTHOLE P O THRISSUR THRISSUR 680003 002151 REKHA M R 74 84 12000.00 D/O N A MALATHY MAANASAM RAGAMALIKAPURAM,THRISSUR KERALA 680004 THARA P D 1204470005875147 VANAJA MUKUNDAN 161 171 11780.00 1/297A PANAKKAL VALAPAD GRAMA PANCHAYAT THRISSUR 680567 000050 HAJI M.M.ABDUL MAJEED 231 241 20000.00 MUKRIAKATH HOUSE VATANAPALLY TRICHUR DIST. KERALA 680614 IN30189511089195 SURENDRAN 245 255 17000.00 KAKKANATT HOUSE KUNDALYUR P O THRISSUR, KERALA 680616 000455 KARUNAKARAN K.K. 280 290 30000.00 KARAYIL THAKKUTTA HOUSE CHENTRAPPINNI TRICHUR DIST. KERALA 680687 MRS. PAMILA KARUNAKARAN 001233 DR RENGIT ALEX 300 310 20000.00 NALLANIRAPPEL PO KAPPADU KANJIRAPPALLY KOTTAYAM DT KERALA 686508 MINU RENGIT 001468 THOMAS JOHN 309 319 20000.00 THOPPIL PEEDIKAYIL KARTHILAPPALLY ALLEPPEY KERALA 690516 THOMAS VARGHESE 000642 JNANAPRAKASH P.S. -

8Th Pune International Film Festival ( 7Th - 14Th January 2010 ) SR

8th Pune International Film Festival ( 7th - 14th January 2010 ) SR. NO. TITLE ORIGINAL TITLE RUNTIME YEAR DIRECTOR COUNTRY OPENING FILM 1 About Elly DARBAREYE ELLY 119 2009 ASGHAR FARHADI IRAN WORLD COMPETITION 1 WHITE LIGHTENIN' - WC WHITE LIGHTNIN' 90 2009 Dominic Murphy UK 2 THE LITTLEONE LA PIVELLINA 100 2009 Tizza Covi, Rainer Frimmel Italy-Austria Alejandro Fernández Almendras - 3 HUACHO - WC HUACHO 89 Chile-France GERMANY CONFIRMED 4 APPLAUSE APPLAUS 86 2009 Martin Zandvliet Denmark CEA MAI FERICITA FATA DIN 5 The happiest girl in the world 100 2009 Radu Jude Romania LUME KIELLETY HEDELMÄ , Dome 6 FORBIDDEN FRUIT -WC 98 2009 Dome Karukoski FINLAND sweden karukoski WHO IS AFRAID OF THE WOLF 7 KDOPAK BY SE VLKA BÁL 90 2008 Maria Procházková czech republic -WC 8 SCRATCH -WC RYSA 89 2009 Michal Rosa poland 9 THE OTHER BANK -WC GAGMA NAPIRI 90 2009 George Ovashvili poland 10 I SAW THE SUN -WC GÜNESI GÖRDÜM 120 2009 Mahsun Kirmizigül. TURKEY THE MAN BEYOND THE BRIDGE- 11 PALTADACHO MUNIS 96 2009 Laxmikant Shetgaonkar INDIA WC 12 FRONTIER BLUES- WC FRONTIER BLUES 95 2009 Babak Jalali Iran-UK-Italy 13 77 DORONSHIP-WC 77 DORONSHIP 90 2009 Pablo Agüero france 14 OPERATION DANUBE-WC OPERACE DUNAJ 104 2009 Jacek Glomb poland 15 THE STRANGER IN ME -WC DAS FREMDE IN MIR 99 2009 Emily Atef GERMANY Marathi competition 1 RITA 145 2009 RENUKA SHAHANE India 2 PAANGIRA 135 2009 RAJEEV PATIL India GOSHTA CHOTI DONGRA 3 GOSHTA CHOTI DONGRA EVDHI 120 2009 NAGESH BHOSALE India EVDHI 4 VIHIR 120 2009 UMESH KULKARNI India 5 A CUP OF TEA EK CUP CHYA 120 -

1 Vision-2011

1 Mercy Vision-2011 VISION-2011 Academic excellence, development of skills and character formation based on the love of God and service of man as modeled in Jesus Christ. The college also aims at training women for the service of God and humanity. MISSION To become a centre of learning par excellence. To provide value- based education To promote quality education aimed at global competence. To ensure an integrated development of individuals. To empower women through education. From the Principal's Desk It is with great joy that the eighth volume of our annual campus newsletter is being released. The pages of this bulletin bear testimony for the academic and non-academic activities of the 48th year of our college and also reflects the attempts made to impart holistic education for our students based on the vision and mission of our pioneers. Placing my deepest gratitude in front of God Almighty, I present….VISION 2011. Dr. Sr. Annamkutty M.J. (Dr. Sr. Kripa) Principal NEW VENTURES Inauguration of the Blessed Pope John Paul II block KARUNYAM, an outreach programme was coordinated by the NAAC coordinator, Dr.W.S.Kottiswari, with the Social Service League as part of post re-accreditation process. It is a continuous process organized with the intention of creating social awareness and commitment in the minds of the younger generation. Students, faculty members and non-teaching staff are actively involved in this programme contributing generously to buy provisions, blankets, adult diapers and cotton clothes for the inmates of the isolated ward, District Hospital, Palakkad. DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH Activities of the Department The activities of the English association for the academic year 2011-12 were inaugurated by Dr.Anto Thomas C. -

11Th Pune International Film Festival ( 10TH - 17TH JANUARY 2013 )

11th Pune International Film Festival ( 10TH - 17TH JANUARY 2013 ) SR. NO. TITLE ORIGINAL TITLE RUNTIME YEAR DIRECTOR COUNTRY OPENING FILM Hayuta and Berl Epilogue 90 2012 Amir Manor Israel WORLD COMPETITION 1 Piata pora roku The Fifth Season of the year 96 2012 Jerzy Domaradzki. Poland 2 Kurmavatara The Tortoise,an incarnation 125 2011 Girish Kasaravalli India 3 Beli Lavovi White Lions 93 2011 Lazar Ristovski Serbia 4 la sirga The Towrope 88 2012 VEGA William Colombia | France | Mexico 5 Pele Akher The Last Step 88 2012 Ali Mosaffa Iran Serbia | Slovenia | Croatia | 6 Parada The Parade 115 2011 Srdjan DRAGOJEVIC Montenegro | Republic of Macedonia 7 Barbara Barbara 105 2012 Christian Petzold Germany 8 Araf Araf/Somewhere in Between 124 2012 Yesim Ustaoglu Turkey | France | Germany 9 Róza Rose 90 2011 Wojciech Smarzowski Poland 10 Silencio en la nieve Frozen Silence 114 2012 Gerardo Herrero Spain | Lithuania 11 La demora The Delay 84 2012 Rodrigo Plá Uruguay | Mexico | France 12 80 milionów 80 Million 110 2011 Waldermar Krzystek Poland 13 Hayuta and Berl Epilogue 90 2012 Amir Manor Israel 14 Hella W 82 2011 Juha Wuolijoki Finland | Estonia MARATHI COMPETITION 1 Tukaram 162 2012 Chandrakant Kulkarni India 2 Samhita The script 138 2012 Sumitra bhave, Sunil sukthankar India 3 Tuhya Dharma Koncha? 118 2012 Satish manwar India 4 Balak Palak BP 100 2012 Ravi jadhav India 5 Kaksparsha 140 2012 Mahesh vaman Manjrekar India 6 Pune 52 120 2012 Nikhil Mahajan India 7 Anumati 120 2012 Gajendra ahire India STUDENT COMPETITION : LIVE ACTION 1 Allah -

2.Hindu Websites Sorted Category Wise

Hindu Websites sorted Category wise Sl. No. Broad catergory Website Address Description Reference Country 1 Archaelogy http://aryaculture.tripod.com/vedicdharma/id10. India's Cultural Link with Ancient Mexico html America 2 Archaelogy http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Harappa Harappa Civilisation India 3 Archaelogy http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Indus_Valley_Civil Indus Valley Civilisation India ization 4 Archaelogy http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kiradu_temples Kiradu Barmer Temples India 5 Archaelogy http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mohenjo_Daro Mohenjo_Daro Civilisation India 6 Archaelogy http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nalanda Nalanda University India 7 Archaelogy http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Taxila Takshashila University Pakistan 8 Archaelogy http://selians.blogspot.in/2010/01/ganesha- Ganesha, ‘lingga yoni’ found at newly Indonesia lingga-yoni-found-at-newly.html discovered site 9 Archaelogy http://vedicarcheologicaldiscoveries.wordpress.c Ancient Idol of Lord Vishnu found Russia om/2012/05/27/ancient-idol-of-lord-vishnu- during excavation in an old village in found-during-excavation-in-an-old-village-in- Russia’s Volga Region russias-volga-region/ 10 Archaelogy http://vedicarcheologicaldiscoveries.wordpress.c Mahendraparvata, 1,200-Year-Old Cambodia om/2013/06/15/mahendraparvata-1200-year- Lost Medieval City In Cambodia, old-lost-medieval-city-in-cambodia-unearthed- Unearthed By Archaeologists 11 Archaelogy http://wikimapia.org/7359843/Takshashila- Takshashila University Pakistan Taxila 12 Archaelogy http://www.agamahindu.com/vietnam-hindu- Vietnam -

Opposing Viewpoints: a Study on Female Representation by Women in Popular Indian Cinema

INTERNATIONALJOURNALOF MULTIDISCIPLINARYEDUCATIONALRESEARCH ISSN:2277-7881; IMPACT FACTOR :6.514(2020); IC VALUE:5.16; ISI VALUE:2.286 Peer Reviewed and Refereed Journal: VOLUME:10, ISSUE:2(5), February:2021 Online Copy Available: www.ijmer.in OPPOSING VIEWPOINTS: A STUDY ON FEMALE REPRESENTATION BY WOMEN IN POPULAR INDIAN CINEMA Mr. Habin. H Ph. D Research Scholar in English T. K. M College of Arts and Science,University of Kerala Karikode, Kollam Abstract Popular Indian film industry has been dominated by men in all its fields. Even though women are involved in all roles including as film producers, film critics, actresses, directors etc., generally, they have been underrepresented and used for the purpose of generating erotic pleasure. This underrepresentation mainly happens in films which are directed by men. Recently, the number of women film makers has been increasing. Majority of films which are directed by women represent women true to their self, projects their problems and works for their betterment. Thus, by analysing certain Indian popular films, the present research paper projects the main notions that such movies try to present and how far those movies are different from those movies which are produced and directed by men. Keywords: Representation, Women, Popular Movies. Introduction In the past, female representations were underrepresented and subjected to the concept of male gaze. Even though there are ‘super woman’ characters in popular films, women are still sexualised. The film sector visages a constant difficulty to trace a sufficient aspect to balance both the sexualisation and betterment of sturdy women. Although representations of women characters have been improved in recent years, the rapid change in attitude happened in the popular Indian industry with the arrival of women directors and script writers. -

Malayalam Film Kilukkam Mp3 Songs Download

Malayalam film kilukkam mp3 songs download click here to download Movie: Kilukkam (K). Release: Category: Malayalam. Director: Priyadarshan. Music: SP Venkatesh. Stars: Mohanlal Innocent Jagathy Sreekumar. Download Kilukkam Malayalam Album Mp3 Songs By Various Here In Full Length. Tags: Kilukkam Malayalam movie Mp3 Songs Free download, Download Kilukkam film Movie Songs, kbps Hq High quality Mp3 Songs, free MP3. Kuttyweb Songs Kuttyweb Ringtones www.doorway.ru Free Mp3 Songs Download Video songs Download Kuttyweb Malayalam Songs Kuttywap Tamil Songs. Kilukkam Mp3 Songs - Mohanlal Hits , Kilukkam Songs Kilukkam Download Kilukkam Film Songs Kilukkam kbps Kilukkam kbps Tamil Songs | Hindi Songs | Malayalam Songs | Telugu Songs | Kannada Songs | English Songs Meena www.doorway.ru Kilukkam Songs Download- Listen Malayalam Kilukkam MP3 songs online free. Play Kilukkam Malayalam movie songs MP3 by S.p. Venkitesh and download. Meenavenalil Kilukkam Song mp3 Download. Meenavenalil Malayalam Film Song Kilukkam mp3. Meena Venalil Full Song | Malayalam Movie "kilukkam". Download Evergreen and New Malayalam Movie Songs @ ONMUSIQ. Kilukkam Full Malayalam mp3 songs,Kilukkam mp3 songs, HQ Mp3 songS, Kilukkam. Neela Venalil, Kilukkam. Download Malayalam song Neela Venalil from Movie Kilukkam! Link As" option. All songs are in mp3 format and bitrate of kbps. Kilukkampetti () Movie Mp3 Songs Added On , This Songs Added Only For Promotional Purposes. Kilukkampetti () Movie Mp3 Songs. 1. Songs Free Download,Mazhathullikilukkam () Mp3 Songs,Mazhathullikilukkam Malayalam Movie Mp3 Songs Free Download,Mazhathullikilukkam. Download Kilukkam Kilukilukkam Various Kilukkam Klukilukkam Mp3 Song Detail: Various is a famous Malayalam Singer and Popular for his Recent Album Malayalam Full Movie Kilukkam Kilukilukkam Ft Mohanlal Jagathy Sreekumar. Mazhathulli kilukkam malayalam movie mp3 songs free download movie name mazhathullikilukkam year Banner sarada pictures cast dileepnbsp.