Pasadena on Her Mind: Exploring Roots of Octavia E. Butler's Fiction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Join Us to “Celebrate Success and Inspire Change”

Pasadena, California Celebrating 50 years of community service Spring 2013 LAND USE / PLANNING EDUCATION OPEN SPACE / CONSERVATION NEIGHBORHOOD SAFETY GOVERNMENT PARKS / RECREATION You’re invited to the WPRA’s 51st annual meeting Join us to “celebrate success and inspire change” he West Pasadena Residents’ Carts will be available for those who need a Association cordially invites members lift to the stadium and back to their car. and other West Pasadena residents to T At 4:45, the evening starts with a reception Save the date attend its 51st annual meeting on Wednesday, and tours of the stadium to witness, first- May 1. The event will be held in the storied, What: hand, the remarkable progress the City has historic Rose Bowl Home Team locker room. WPRA annual meeting made in modernizing America’s Stadium. “Celebrating success and inspiring change” is During the reception period, attendees can When: the theme. enjoy light dinner fare, while visiting with Wednesday, May 1 The annual meeting is open to the public and the many community organizations that’ll be 5:30-8:30 pm free of charge. Free parking is available to all exhibiting. in Lot F. Enter the stadium through Gate A. Parking-Entry: At 6:30, the main program opens with a celebration of Pasadena life as seen Parking lot F through the eyes of the late iconic television Enter through Gate A personality Huell Howser. Best known for his travel show, California’s Gold, which aired for Where: many years on Public Broadcasting station Rose Bowl KCET, Howser died in January. -

Octavia E. Butler Telling My Stories

Octavia E. Butler Telling My Stories Library, West Hall April 8–August 7, 2017 1 Octavia E. Butler (1947–2006) was a pioneer, a trailblazing storyteller who brought her voice— the voice of a woman of color—to science fiction. Her fresh approach to what some might consider a nonliterary genre framed serious and often controversial topics through a literary lens. Tackling subjects such as power, race, gender, sexuality, religion, economic and social status, the environment, and humanity, Butler combined the tropes of science fiction and fantasy with a tightly rendered and entertaining prose style. These are her stories. Her deeply developed characters contend with extraordinary situations, revealing the best and worst of the human species. As the first African American woman writer in the field of science fiction, Butler faced pressures and challenges from inside and outside her community. Tired of science fiction stories featuring only white male heroes, Butler took action. “I can write my own stories and I can write myself in,” as she liked to say, and in the process she created a new identity as a black woman role model and an award-winning author. She published 12 novels and a volume of short stories and essays before her untimely passing in 2006. “Octavia E. Butler: Telling My Stories” draws on the author’s manuscripts, correspondence, papers, and photographs, bequeathed to The Huntington, to explore the life and works of this remarkable woman. Octavia Estelle Butler was born in Pasadena, Calif., on June 22, 1947. Butler discovered writing at an early age, finding that this activity suited her shy nature, her strict Baptist upbringing, and her intellectual curiosity. -

Octavia E. Butler Papers

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c8fn17qs No online items Octavia E. Butler Papers Huntington Library. Manuscripts Department Huntington Library. Manuscripts Department 1151 Oxford Road San Marino, California 91108 (626) 405-2100 [email protected] http://www.huntington.org/huntingtonlibrary.aspx?id=554 2013 Octavia E. Butler Papers mssOEB 1-8000 1 Descriptive Summary Title: Octavia E. Butler Papers Dates: 1933-2006 Collection Number: mssOEB 1-8000 Creator/Collector: Butler, Octavia E. Extent: 8000 pieces in 354 boxes, 1 volume, 2 binders, and 18 broadsides. Repository: Huntington Library. Manuscripts Department San Marino, California 91108 Abstract: The personal and professional papers of American science fiction author Octavia E. Butler. Language of Material: English Access The collection is open for qualified researchers as of Nov. 1, 2013. Publication Rights The literary copyright of materials by Octavia E. Butler is held by the Estate of Octavia E. Butler. Anyone wishing to quote from or publish any manuscript material by Octavia E. Butler must contact the agent listed below. Questions should also be directed to the agent below. Agent contact info: Merrilee Heifetz Writers House 21 West 26th St New York City, NY 10010 [email protected] (212) 685-2605 The copyright for materials by others represented in the collection is held by other parties. It is the responsibility of the researcher to determine the current copyright holder and obtain permission from the appropriate parties. The Huntington Library retains the physical rights to the material. In order to quote from, publish, or reproduce any of the manuscripts or visual materials, researchers must obtain formal permission from the office of the Library Director, in addition to permission obtained from any copyright holders. -

5 Around San Gabriel Valley

Fire Prevention Festival at the Sierra Madre Fire Department Saturday, Oct. 17th - 11:00 a.m. to 2:00 p.m. SATURDAY, OCTOBER 17, 2015 VOLUME 9 NO. 42 MEET SIERRA MADRE’S 2016 PRINCESSES UTILITY USER TAX MEASURE HEADED FOR APRIL BALLOT On Tuesday, the Sierra Madre the city. “I want facts, not spin”, City Council unanimously agreed said Delmar when referring to the to move forward with the necessary upcoming ballot measure. steps to place a Utility User Tax Mayor Pro Tem Gene Goss and Measure on the April 2016 ballot. Councilman John Harabedian both The decision follows in part the favored following the committee’s recommendation of the Revenue recommendation of increasing Committee, however the measure the tax to 12%. There was even will only ask for a 10% UUT. The discussion of raising the tax to 11%. committee’s recommendation was In the final analysis the 10% figure for an 12% increase. gained the support of all five council The current UUT will bottom out members. in the next fiscal year at 6% leaving Residents attitude towards an the city with an estimated $1 million increase in the UUT appears to have dollar shortfall. changed since the last time the issue Although the last attempt to was presented to voters. The city maintain the UUT at 10% failed to has held several community input get voter approval in 2014, the city’s meetings and a citywide Town Hall current financial position along with meeting. As a result, the consensus of an apparent shift in public sentiment those attending was that an increase has convinced all members of the in the tax is needed. -

Octavia Butler Strategic Reader Collected from the Octavia Butler Symposium, Allied Media Conference 2010 and Edited by Adrienne Maree Brown & Alexis Pauline Gumbs

Octavia Butler Strategic Reader collected from the Octavia Butler Symposium, Allied Media Conference 2010 and edited by Adrienne Maree Brown & Alexis Pauline Gumbs Table of Contents: - Intro - What is Emergent Strategy - Octavia’s Work as a Whole Identity Transformation Apocalypse Impact - Specific Series/Stories Patternist (Wild Seed, Mind of My Mind, Clay’s Ark, Patternmaster) Lilith’s Brood/Xenogenesis (Dawn, Adulthood Rites, Imago) Parables (Parable of the Sower, Parable of the Talents) Other Stories - Other Relevant Work Mentioned (music, writers, etc) Intro This reader emerged out of the Octavia Butler Symposium at the Allied Media Conference in 2010. The symposium happened in 3 parts - a) an initial presentation by host/editor Adrienne Maree Brown, b) a fishbowl conversation where everyone in the group participated in addressing meta-questions about Octavia's work, and c) several small group conversations on particular series. Groups have since started reading circles, strategic circles and other gatherings around Octavia's work in their local cities/regions. This is by no means a comprehensive or complete reader - there are books (Kindred, Fledgling, Survivor) that are barely touched on. We hope that this can be a growing reader which both helps people see Octavia’s work in a new light and serves as a collecting point for thinking about her work. What follows are strategic questions to consider about Octavia's work as a whole, and then about specific series/stories. We invite feedback and additions. "We are all vibrations. The moment we share here is a preparation for the next moment. Octavia leaves her writing in order to prepare us for the next meeting." "Being able to create and imagine bigger is a process of decolonization of our dreams. -

Experience, Research, and Writing: Octavia E. Butler As an Author Of

Experience, Research, and Writing Octavia E. Butler as an Author of Disability Literature Sami Schalk In a journal entry on November 12, 1973, Octavia E. Butler writes: “I should stay healthy! The bother and worry of being sick and not being able to afford to do anything but complain about the pain and hope it goes away is Not conducive to good (or prolific) writing.”1 At this time, at the age of twenty-six, Butler had not yet sold her first novel. She was just on the cusp of what would be an incredible writing career, starting with her first novel, Patternmaster, published a mere three years later. But in 1973,Butler was an essentially unknown and struggling writer who regularly battled poverty, health, and her own harsh inner critic. From the outset of her career, Butler’s texts have been lauded, critiqued, and read again and again in relationship to race, gender, and sexuality. Only recently, however, has her work been taken up in respect to disability.2 Therí A. Pickens argues,“Situating disability at or near the center of Butler’s work (alongside race and gender) lays bare how attention to these categories of analysis shifts the conversation about the content of Butler’s work.”3 Building upon Pickens and other recent work on Butler and disability, I seek to change conversations about Butler’s work among feminist, race, and genre studies scholars while also encouraging more attention to Butler by disability studies scholars. In this article, I use evidence from Butler’s personal papers, public interviews, and publications to position Butler as an author of disability literature due to her lived experi- ences, her research, and her writing. -

Hamparian Thesis.Pdf (320.3Kb)

Matt Hamparian 1 Women of Science Fiction in the 1970s Introduction Science fiction is the genre of possibility, and is nearly boundless. The only limitation is that of what the reader and writer can imagine. What drew me to both science fiction, and this research is what draws many to science fiction: exploring new worlds, new ideas, new species, but importantly the depths of the human mind. Science fiction of the 1970s was transformative for the genre, as there was a distinct shift on who was writing best selling and award winning novels. Men had long dominated science fiction, especially during the “golden age,” but during the 1970s published science fiction novels by women gained the attention of those who loved the genre. Women such as Ursula K. Le Guin, Joanna Russ, Kate Wilhelm, and James Tiptree Jr. (Allison B. Sheldon), all wrote award winning science fiction, but their stories also challenged readers with themes of equality. The question then arises, why did so many female authors take to science fiction to express their messages of equality during the 1970s? Author Suzy McKee Charnas, author of The Holdfast Chronicles wrote of this in the Khatru Symposium: Women in Science Fiction: “instead of having to ‘twist’ reality in order to create ‘realistic’ female characters in today’s totally unfree society, the sf writer can create the societies that would produce those characters” (Charnas 4). The women of science fiction in the 1970s were responding to an issue in science fiction: women were not represented accurately in text, nor where they given the same chance as their male counterparts. -

Archive I: Down by the Old Slipstream

Archive I: who gets a whole lot less recognition than I for one think he deserves: Barrington J. Bayley. Down by the Old Slipstream Bayley is an unusual writer in a variety of Arthur D. Hlavaty, 206 Valentine Street, ways. One can see him as a strange sort of Yonkers, NY 10704-1814. 914-965-4861. amphibian, in that he has been most published by [email protected] New Worlds and by DAW. He is not a writer one <http://www.livejournal.com/users/supergee/> seeks out for literary merit, characterization, elegant <http://www.maroney.org/hlavaty/> prose, adventure, or sex. If anything, he can be © 2018 by Arthur D. Hlavaty. Staff: Bernadette compared with writers such as Clement, Niven, Bosky, Kevin J. Maroney, Shekinah Dax, and the and Hogan,* who seek to do only one thing in their Valentine’s Castle Rat Pack. Permission to reprint in any nonprofit publication is hereby granted, on sf. But while the others speculate scientifically, condition that I am credited and sent a copy. Bayley deals with philosophical and spiritual questions, matters of the essence of reality. This is a new idea. If I do more of these, they Bayley has been largely concerned with the nature of Time in his writings, and perhaps his two will go to efanzines but may not be sent best books until now, Collision Course and The Fall of postally or as .txt files. If you want to stay on Chronopolis, presented new approaches to this either mailing list for these, please reply. Nice problem. More recently, he has incorporated such Distinctions will continue as before. -

SCIENCE FICTION FALL T)T1T 7TT?TI7 NUMBER 48 1983 Mn V X J J W $2.00 SCIENCE FICTION REVIEW (ISSN: 0036-8377) P.O

SCIENCE FICTION FALL T)T1T 7TT?TI7 NUMBER 48 1983 Mn V X J_J W $2.00 SCIENCE FICTION REVIEW (ISSN: 0036-8377) P.O. BOX 11408 PORTLAND, OR 97211 AUGUST, 1983 —VOL.12, NO.3 WHOLE NUMBER 98 PHONE: (503) 282-0381 RICHARD E. GEIS—editor & publisher PAULETTE MINARE', ASSOCIATE EDITOR PUBLISHED QUARTERLY FEB., MAY, AUG., NOV. SINGLE COPY - $2.00 ALIEN THOUGHTS BY THE EDITOR.9 THE TREASURE OF THE SECRET C0RDWAINER by j.j. pierce.8 LETTERS.15 INTERIOR ART-- ROBERT A. COLLINS CHARLES PLATT IAN COVELL E. F. BLEILER ALAN DEAN FOSTER SMALL PRESS NOTES ED ROM WILLIAM ROTLSER-8 BY THE EDITOR.92 KERRY E. DAVIS RAYMOND H. ALLARD-15 ARNIE FENNER RICHARD BRUNING-20199 RONALD R. LAMBERT THE VIVISECTOR ATOM-29 F. M. BUSBY JAMES MCQUADE-39 BY DARRELL SCHWEITZER.99 ELAINE HAMPTON UNSIGNED-35 J.R. MADDEN GEORGE KOCHELL-38,39,90,91 RALPH E. VAUGHAN UNSIGNED-96 ROBERT BLOCH TWONG, TWONG SAID THE TICKTOCKER DARRELL SCHWEITZER THE PAPER IS READY DONN VICHA POEMS BY BLAKE SOUTHFORK.50 HARLAN ELLISON CHARLES PLATT THE ARCHIVES BOOKS AND OTHER ITEMS RECEIVED OTHER VOICES WITH DESCRIPTION, COMMENTARY BOOK REVIEWS BY AND OCCASIONAL REVIEWS.51 KARL EDD ROBERT SABELLA NO ADVERTISING WILL BE ACCEPTED RUSSELL ENGEBRETSON TEN YEARS AGO IN SF - SUTER,1973 JOHN DIPRETE BY ROBERT SABELLA.62 Second Class Postage Paid GARTH SPENCER at Portland, OR 97208 THE STOLEN LAKE P. MATHEWS SHAW NEAL WILGUS ALLEN VARNEY Copyright (c) 1983 by Richard E. MARK MANSELL Geis. One-time rights only have ALMA JO WILLIAMS been acquired from signed or cred¬ DEAN R. -

Our Energy, Insight Will Carry Us Through an Uncertain Future

Pasadena, California Celebrating 58 years of community service Summer 2020 LAND USE/PLANNING WPRA IN MOTION OPEN SPACE / NATURAL RESOURCES NEIGHBORHOOD SAFETY BREAKING NEWS COMMUNITY Our energy, insight will carry us through an uncertain future By Bill Bogaard Former Pasadena mayor and Red-carpet wishes for the real stars WPRA president “Next year I don’t wanna hear about the Oscars or Golden Globes. I don’t want to see a s 2019 drew to a close, Pasadena had single pathetic actor, actress, singer, celebrity or sports person on any red carpet! Next no reason to think that the new year year I want to see nurses, doctors, ambulance crews, care-givers, support workers, police Awould not live up to the theme of the officers, firefighters, shop clerks, grocery store workers, garbage removal crews, delivery 2020 Rose Parade, “The Power of Hope.” The drivers and truck drivers, having free red-carpet parties with awards and expensive goody economy was vibrant, unemployment was bags. If this doesn’t happen it will be the biggest injustice ever!” historically low, and the stock market near — Thanks to Lorraine Clearman, who found this in a Pasadena Next Door app post an all-time high. The new year did pose challenges, of course, the Spanish flu sped across the world, killing City Hall and its Public Health Department such as overdevelopment, affordable housing more than 675,000 in America and as many stepped up to maintain municipal services and homelessness, increasing traffic and as 50 million worldwide. This new pandemic, and to address the many community needs economic disparity between rich and poor. -

THR 1976 1.Pdf

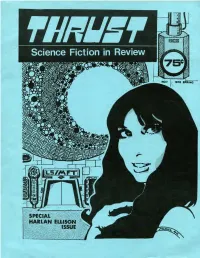

creative writers and artists appear in rounter tfjrusit COLLEGE PARK, MD. 20740 50C thrust contents Cover by Steve Hauk.....page 1 Contents page (art by Richard Bryant).page 3 Editorial by Doug Fratz (art by Steve Hauk).page 4 THRUST INTERVIEW: HARLAN ELLISON by Dave Bischoff and Chris Lampton (axt by Steve Hauk)...page 5 Alienated Critic by Doug Fratz (art by Don Dagenais).page 12 Conventions (art by Jim Rehak).page 13 Centerspread art by Richard Bryant.page 14 Harlan Ellison vs. The Spawning Bischii by David F. Bischoff.page 16 Book Reviews by Chris Lampton, Linda Isaacs, Dave Bischoff, Melanie Desmond and Doug Fratz (art by Richard Bryant and Dennis Bailey ).page 21 ADVERTISING: Counter-Thrust Fantasy Magazine...page 2 The Nostalgia Journal.....page 27 Crazy A1 ’ s C omix and Nostalgia Shop....page 28 staff Editor-in-Chief: Computer Layout: LEE MOORE and NATALIE PAYMER Doug Fratz Art Director: Managing Editor: STEVE HAUK Editorial Assistants: Dennis Bailey RON WATSON and BARBARA GOLDFARB Staff Writers: Associate Editor: DAVE BISCHOFF Melanie Desmond EE SEE? EDITORIAL by Doug Fratz I created THRUST SCIENCE FICTION more than find it incredibly interesting reading it over three years ago, and edited and published five for the tenth or twelveth time. Ted Cogswell issues, between February 1973 and May 1974, should take special note. completely from my own funds. When I received In addition, THRUST will have a sister my degree from the University of Maryland, I magazine of sorts, COUNTER-THRUST, to be pub¬ decided to turn THRUST over to other editors. lished yearly, once each summer. -

OCTAVIA BUTLER NOW J21COLORED Copy THE+

★ ★ OCTAVIA BUTLER NOW! READING RACE, GENDER, AND CRITICAL FUTURES FALL 2021 ENGL A490.001 | Great Figures TR 3:30-4:45 | Location TBA Loyola University New Orleans Prof. R. Scott Heath [email protected] ★ ★ OCTAVIA BUTLER NOW! READING RACE, GENDER, AND CRITICAL FUTURES Dr. R. S. Heath ENGL A490.001 (Great Figures: Octavia Butler) Office: 316 Bobet Hall Fall 2021 Hours: MW by appointment TR 3:30-4:45P Email: [email protected] Course Description Octavia E. Butler might be called the patron saint of black science fiction, a literary genre sometimes classified as Afrofuturism. Recently, her likeness and her ideas—especially those conveyed in her novels Kindred and Parable of the Sower—have been trending publicly, proving stunningly resonant and possibly prophetic in these uncertain times. For centuries, black writers and artists have theorized and continually revised aesthetic modes for the representation of American subjectivity, especially with regard to and in response to conventions of race, class, gender, sexuality, and nationality in the United States. Presently, the country is being met with a set of intersecting, interconnected crises—a global health emergency, an economic collapse, a social upheaval, a climate firestorm, a political spiral—that have required our isolation while simultaneously inspiring monumental collective action. The disproportionately distributed impact of these overlapping catastrophes has driven ongoing conflicts emergent along reliable fault lines of blackness and Americanness, difference and belonging. Octavia Butler operates as a metacritic, writing herself into a framework not designed with her in mind, transforming the mechanism while intimately illustrating and explicating our own alienation. In this single-author, seminar-style course we will examine Butler’s long fiction in its entirety—along with a cache of screen media—tracing its continuity of themes and discerning its usefulness in our current cultural context.