Information to Users

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Songs by Artist

Reil Entertainment Songs by Artist Karaoke by Artist Title Title &, Caitlin Will 12 Gauge Address In The Stars Dunkie Butt 10 Cc 12 Stones Donna We Are One Dreadlock Holiday 19 Somethin' Im Mandy Fly Me Mark Wills I'm Not In Love 1910 Fruitgum Co Rubber Bullets 1, 2, 3 Redlight Things We Do For Love Simon Says Wall Street Shuffle 1910 Fruitgum Co. 10 Years 1,2,3 Redlight Through The Iris Simon Says Wasteland 1975 10, 000 Maniacs Chocolate These Are The Days City 10,000 Maniacs Love Me Because Of The Night Sex... Because The Night Sex.... More Than This Sound These Are The Days The Sound Trouble Me UGH! 10,000 Maniacs Wvocal 1975, The Because The Night Chocolate 100 Proof Aged In Soul Sex Somebody's Been Sleeping The City 10Cc 1Barenaked Ladies Dreadlock Holiday Be My Yoko Ono I'm Not In Love Brian Wilson (2000 Version) We Do For Love Call And Answer 11) Enid OS Get In Line (Duet Version) 112 Get In Line (Solo Version) Come See Me It's All Been Done Cupid Jane Dance With Me Never Is Enough It's Over Now Old Apartment, The Only You One Week Peaches & Cream Shoe Box Peaches And Cream Straw Hat U Already Know What A Good Boy Song List Generator® Printed 11/21/2017 Page 1 of 486 Licensed to Greg Reil Reil Entertainment Songs by Artist Karaoke by Artist Title Title 1Barenaked Ladies 20 Fingers When I Fall Short Dick Man 1Beatles, The 2AM Club Come Together Not Your Boyfriend Day Tripper 2Pac Good Day Sunshine California Love (Original Version) Help! 3 Degrees I Saw Her Standing There When Will I See You Again Love Me Do Woman In Love Nowhere Man 3 Dog Night P.S. -

Cosmos: a Spacetime Odyssey (2014) Episode Scripts Based On

Cosmos: A SpaceTime Odyssey (2014) Episode Scripts Based on Cosmos: A Personal Voyage by Carl Sagan, Ann Druyan & Steven Soter Directed by Brannon Braga, Bill Pope & Ann Druyan Presented by Neil deGrasse Tyson Composer(s) Alan Silvestri Country of origin United States Original language(s) English No. of episodes 13 (List of episodes) 1 - Standing Up in the Milky Way 2 - Some of the Things That Molecules Do 3 - When Knowledge Conquered Fear 4 - A Sky Full of Ghosts 5 - Hiding In The Light 6 - Deeper, Deeper, Deeper Still 7 - The Clean Room 8 - Sisters of the Sun 9 - The Lost Worlds of Planet Earth 10 - The Electric Boy 11 - The Immortals 12 - The World Set Free 13 - Unafraid Of The Dark 1 - Standing Up in the Milky Way The cosmos is all there is, or ever was, or ever will be. Come with me. A generation ago, the astronomer Carl Sagan stood here and launched hundreds of millions of us on a great adventure: the exploration of the universe revealed by science. It's time to get going again. We're about to begin a journey that will take us from the infinitesimal to the infinite, from the dawn of time to the distant future. We'll explore galaxies and suns and worlds, surf the gravity waves of space-time, encounter beings that live in fire and ice, explore the planets of stars that never die, discover atoms as massive as suns and universes smaller than atoms. Cosmos is also a story about us. It's the saga of how wandering bands of hunters and gatherers found their way to the stars, one adventure with many heroes. -

Just the Right Song at Just the Right Time Music Ideas for Your Celebration Chart Toppin

JUST THE RIGHT SONG AT CHART TOPPIN‟ 1, 2 Step ....................................................................... Ciara JUST THE RIGHT TIME 24K Magic ........................................................... Bruno Mars You know that the music at your party will have a Baby ................................................................ Justin Bieber tremendous impact on the success of your event. We Bad Romance ..................................................... Lady Gaga know that it is so much more than just playing the Bang Bang ............................................................... Jessie J right songs. It‟s playing the right songs at the right Blurred Lines .................................................... Robin Thicke time. That skill will take a party from good to great Break Your Heart .................................. Taio Cruz & Ludacris every single time. That‟s what we want for you and Cake By The Ocean ................................................... DNCE California Girls ..................................................... Katie Perry your once in a lifetime celebration. Call Me Maybe .......................................... Carly Rae Jepson Can‟t Feel My Face .......................................... The Weeknd We succeed in this by taking the time to get to know Can‟t Stop The Feeling! ............................. Justin Timberlake you and your musical tastes. By the time your big day Cheap Thrills ................................................ Sia & Sean Paul arrives, we will completely -

10CC Dreadlock Holiday 98 Degrees Because of You Aaron Neville Don

10CC My Love My Life Dreadlock Holiday One Of Us Our Last Summer 98 Degrees Rock Me Because Of You S.O.S. Slipping Through My Fingers Aaron Neville Super Trouper Don't Know Much (Duet Linda Ronstad) Take A Chance On Me For The Goodtimes Thank You For The Music The Grand Tour That's Me The Name Of The Game Aaron Tippin The Visitors Ain't Nothin' Wrong With The Radio The Winner Takes It All Kiss This Tiger Two For The Price Of One Abba Under Attack Andante, Andante Voulez Vous Angel Eyes Waterloo Another Town, Another Train When All Is Said And Done Bang A Boomerang When I Kissed The Teacher Chiquitita Why Did It Have To Be Me Dance (While The Music Still Goes On) Dancing Queen Abc Does Your Mother Know Poison Arrow Dum Dum Diddle The Look Of Love Fernando Gimme! Gimme! Gimme! (A Man After Midnight) Ac Dc Happy New Year For Those About To Rock Hasta Manana Have A Drink On Me He Is Your Brother Highway To Hell Hey Hey Helen Who Made Who Honey Honey Whole Lotta Rosie I Do, I Do, I Do You Shook Me All Night Long I Have A Dream I Let The Music Speak Ace Of Base I Wonder All That She Wants If It Wasn't For The Nights Beautiful Life I'm A Marionette Cruel Summer I've Been Waiting For You Don't Turn Around Kisses Of Fire Life Is A Flower Knowing Me Knowing You Lucky Love Lay All Your Love On Me The Sign Lovers(Live A Little Longer) Wheel Of Fortune Mamma Mia Money Money Money Ad Libs The Engelstalige Karaoke Holding de Riddim Entertainment Pagina 1 Boy From New York City Theme From Moonlighting Adele Al Jolson Don't You Remember Avalon I Set Fire -

PLAYNOTES Season: 44 Issue: 07

PLAYNOTES SEASON: 44 ISSUE: 07 BACKGROUND INFORMATION INTERVIEWS & COMMENTARY Discussion Series The Artistic Perspective, hosted by Artistic Director Anita Stewart, is an opportunity for audience members to delve deeper into the themes of the show through conversation with special guests. A different scholar, visiting artist, playwright, or other expert will join the discussion each time. The Artistic Perspective discussions are held after the first Sunday matinee performance. Page to Stage discussions are presented in partnership with the Portland Public Library. These discussions, led by Portland Stage artistic staff, actors, directors, and designers answer questions, share stories and explore the challenges of bringing a particular play to the stage. Page to Stage occurs at noon on the Tuesday after a show opens at the Portland Public Library’s Main Branch. Curtain Call discussions offer a rare opportunity for audience members to talk about the production with the performers. Through this forum, the audience and cast explore topics that range from the process of rehearsing and producing the text to character development to issues raised by the work Curtain Call discussions are held after the second Sunday matinee performance. All discussions are free and open to the public. Show attendance is not required. To subscribe to a discussion series performance, please call the Box Office at 207.774.0465. FRIENDS, LIKE SARAH AND RUTH, SHARING WINE AND SMILES. Portland Stage Company Educational Programs are generously supported through the annual donations of hundreds of individuals and businesses, as well as special funding from: George & Cheryl Higgins The Onion Foundation The Davis Family Foundation Our Education Media partner is Sex and Other Disturbances is a recipient of a 2017 Edgerton Foundation New Play Award. -

Narratives of Two Mothers on Raising Their Children with Disabilities

University of Northern Iowa UNI ScholarWorks Dissertations and Theses @ UNI Student Work 2016 "Joy for what it is": Narratives of two mothers on raising their children with disabilities Zeina H. Yousof University of Northern Iowa Let us know how access to this document benefits ouy Copyright ©2016 Zeina H. Yousof Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uni.edu/etd Part of the Special Education and Teaching Commons Recommended Citation Yousof, Zeina H., ""Joy for what it is": Narratives of two mothers on raising their children with disabilities" (2016). Dissertations and Theses @ UNI. 345. https://scholarworks.uni.edu/etd/345 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Work at UNI ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations and Theses @ UNI by an authorized administrator of UNI ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Copyright by ZEINA H. YOUSOF 2016 All Rights Reserved “JOY FOR WHAT IS”: NARRATIVES OF TWO MOTHERS ON RAISING THEIR CHILDREN WITH DISABILITIES An Abstract of a Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Education Approved: ________________________________ Dr. Amy J. Petersen, Committee Chair ________________________________ Dr. Kavita Dhanwada, Dean of the Graduate College Zeina H. Yousof University of Northern Iowa December 2016 ABSTRACT The purpose of this study was to explore the experiences of two mothers of children with disabilities on parenting their children and navigating the world of disabilities. For many parents, the diagnosis of a child with disabilities represents a form of interpersonal loss through the loss of the imagined child. -

Ace of Base Lucky Love Mp3, Flac, Wma

Ace Of Base Lucky Love mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Electronic / Pop Album: Lucky Love Country: Japan Released: 1996 Style: Europop, Synth-pop MP3 version RAR size: 1621 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1134 mb WMA version RAR size: 1589 mb Rating: 4.5 Votes: 395 Other Formats: VQF DTS MMF MP1 ASF MP2 VOX Tracklist Hide Credits Lucky Love (Frankie Knuckles Classic Club Mix) A1 Engineer – John PoppoKeyboards – Satoshi Tomiie, Terry BurrusRemix, Producer [Additional Production By] – Frankie Knuckles Lucky Love (Lenny B's Club Mix) A2 Programmed By, Keyboards – Lenny BertoldoRemix, Producer [Additional Production By] – Lenny Bertoldo, Marc "DJ Stew" Pirrone* A3 Lucky Love (Acoustic Version) Lucky Love (Vission Lorimer Funkdified Mix) B1 Remix – Vission Lorimer*Remix, Producer [Additional Production By] – Pete Lorimer*, Richard "Humpty" Vission Lucky Love (Armand's British Nites Mix) B2 Remix, Producer [Additional Production By] – Armand Van Helden Companies, etc. Phonographic Copyright (p) – Mega Records Copyright (c) – Arista Records, Inc. Manufactured By – Arista Records, Inc. Produced For – Def Mix Productions Produced For – Powertools Production Produced For – Peewee Productions Produced For – Cheiron Productions Produced For – X-Mix Productions Recorded At – Cheiron Studios Mixed At – Cheiron Studios Published By – Megasong Publishing Published By – Jerk Awake Published By – EMI Music Publishing Credits Lyrics By – Billy Steinberg, Jonas "Joker" Berggren Management – Basic Music Management, Lasse Karlsson Music By – Jonas -

Access the Best in Music. a Digital Version of Every Issue, Featuring: Cover Stories

Bulletin YOUR DAILY ENTERTAINMENT NEWS UPDATE MARCH 23, 2020 Page 1 of 27 INSIDE Lil Uzi Vert’s ‘Eternal Atake’ Spends • Roddy Ricch’s Second Week at No. 1 on ‘The Box’ Leads Hot 100 for 11th Week, Billboard 200 Albums Chart Harry Styles’ ‘Adore You’ Hits Top 10 BY KEITH CAULFIELD • What More Can (Or Should) Congress Do Lil Uzi Vert’s Eternal Atake secures a second week No. 1 for its first two frames on the charts dated Dec. to Support the Music at No. 1 on the Billboard 200 albums chart, as the set 28, 2019 and Jan. 4, 2020. Community Amid earned 247,000 equivalent album units in the U.S. in Eternal Atake would have most likely held at No. Coronavirus? the week ending March 19, according to Nielsen Mu- 1 for a second week without the help of its deluxe • Paradigm sic/MRC Data. That’s down just 14% compared to its reissue. Even if the album had declined by 70% in its Implements debut atop the list a week ago with 288,000 units. second week, it still would have ranked ahead of the Layoffs, Paycuts The small second-week decline is owed to the chart’s No. 2 album, Lil Baby’s former No. 1 My Turn Amid Coronavirus album’s surprise reissue on March 13, when a new (77,000 units). The latter set climbs two rungs, despite Shutdown deluxe edition arrived with 14 additional songs, a 27% decline in units for the week.Bad Bunny’s • Cost of expanding upon the original 18-song set. -

A Critical Grounded Theory of the Development of Student Leaders with Historically Marginalized Identities

“Everything I Did Was Black. That’s What I Was There For.”: A Critical Grounded Theory of the Development of Student Leaders with Historically Marginalized Identities Item Type text; Electronic Dissertation Authors Womble, Allen A. Citation Womble, Allen A. (2021). “Everything I Did Was Black. That’s What I Was There For.”: A Critical Grounded Theory of the Development of Student Leaders with Historically Marginalized Identities (Doctoral dissertation, University of Arizona, Tucson, USA). Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction, presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 26/09/2021 11:58:53 Item License http://rightsstatements.org/vocab/InC/1.0/ Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/660217 “EVERYTHING I DID WAS BLACK. THAT’S WHAT I WAS THERE FOR.”: A CRITICAL GROUNDED THEORY OF THE DEVELOPMENT OF STUDENT LEADERS WITH HISTORICALLY MARGINALIZED IDENTITIES by Allen A. Womble __________________________________ Copyright © Allen A. Womble 2021 A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATIONAL POLICY STUDIES AND PRACTICE In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2021 THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA GRADUATE COLLEGE As members of the Dissertation Committee, we certify that we have read the dissertation prepared by: Allen Alfred Womble titled: “EVERYTHING I DID WAS BLACK. THAT’S WHAT I WAS THERE FOR.”: and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the dissertation requirement for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy. -

Band Song-List

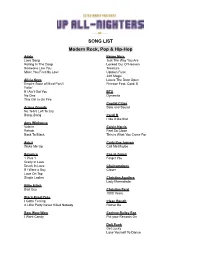

SONG LIST Modern Rock, Pop & Hip-Hop Adele Bruno Mars Love Song Just The Way You Are Rolling In The Deep Locked Out Of Heaven Someone Like You Treasure Make You Feel My Love Uptown Funk 24K Magic Alicia Keys Leave The Door Open Empire State of Mind Part II Finesse Feat. Cardi B Fallin' If I Ain't Got You BTS No One Dynamite This Girl Is On Fire Capital Cities Ariana Grande Safe and Sound No Tears Left To Cry Bang, Bang Cardi B I like it like that Amy Winhouse Valerie Calvin Harris Rehab Feel So Close Back To Black This is What You Came For Avicii Carly Rae Jepsen Wake Me Up Call Me Maybe Beyonce Cee-lo Green 1 Plus 1 Forget You Crazy In Love Drunk In Love Chainsmokers If I Were a Boy Closer Love On Top Single Ladies Christina Aguilera Lady Marmalade Billie Eilish Bad Guy Christina Perri 1000 Years Black-Eyed Peas I Gotta Feeling Clean Bandit A Little Party Never Killed Nobody Rather Be Bow Wow Wow Corinne Bailey Rae I Want Candy Put your Records On Daft Punk Get Lucky Lose Yourself To Dance Justin Timberlake Darius Rucker Suit & Tie Wagon Wheel Can’t Stop The Feeling Cry Me A River David Guetta Love You Like I Love You Titanium Feat. Sia Sexy Back Drake Jay-Z and Alicia Keys Hotline Bling Empire State of Mind One Dance In My Feelings Jess Glynne Hold One We’re Going Home Hold My Hand Too Good Controlla Jessie J Bang, Bang DNCE Domino Cake By The Ocean Kygo Disclosure Higher Love Latch Katy Perry Dua Lipa Chained To the Rhythm Don’t Start Now California Gurls Levitating Firework Teenage Dream Duffy Mercy Lady Gaga Bad Romance Ed Sheeran Just Dance Shape Of You Poker Face Thinking Out loud Perfect Duet Feat. -

Bob Marshall Wilderness Complex 2014 HIGHLIGHTED ARTICLES

Bob Marshall Wilderness Complex 2014 HIGHLIGHTED ARTICLES Raising Babies in the Bob 4 Celebrate! Celebrate! Partnering for the 6 It’s the 50th Anniversary of the Wilderness Act! Future of Fire Lookouts Letter From BMWC Lead Ranger—Deb Mucklow Native Trout Restoration 7 on the NF of the Black- You’re Invited to the annual public meeting for the Bob Marshall Wilderness Com- foot plex Saturday March 29, 2014, at the Choteau Library meeting room, starting time 10 am. The library is on Main Street and to best access the conference room, park directly south One Story, One Memory, 8 or One Place at a time of Rex’s Grocery Store and enter at the back of the library from Main Street. We’ll have signs posted so all will be able to find us! Some of you recognize this as the “LAC” (Limits of Ac- th Elk for the Future? 11 ceptable Change) meeting or task force. This year we are focusing on the “50 Anniversary Celebration of the Wilderness Act”. Back to Basics: Bridging 16 This annual meeting is for all interested par- the Traditional Skills Gap ties to talk about the Bob Marshall, Scape- goat and Great Bear Wilderness areas. As Inside Story 6 wilderness stewards and managers, we need Annual BMWC to hear what do you think is working, what is Public Meeting not and areas of concern you may have. Agenda Please give me a call (406-387-3851) or • 50th anniversary wilder- email ([email protected]) to let me know ness activities and how what topics you’d like for us to present. -

Defense Generated Impasse: the Patient's Experience of the Analyst's

Defense Generated Impasse: The Patient’s Experience of the Analyst’s Defensiveness1 Cheryl Chenot, Psy.D., MFT Institute of Contemporary Psychoanalysis Los Angeles, California 2000, 2012 ∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞∞ Any or all of this document may not be reproduced without the consent of the author. 1 This paper is about healthy and dysfunctional conversation. This paper emerged thanks to rich conversations with people who contributed thoughts and perceptions, and who helped me to clarify my ideas over the four year evolution of this paper. Their voices are to be found throughout the paper. Many thanks to Gary Sattler, Lolita Sapriel and William Coburn for their conceptual contributions, and to Elizabeth Altman and Carol Fahy for their thoughtful suggestions about form and structure. I also wish to express my gratitude to the many people who encouraged me in diverse ways, who are too numerous to mention in an exhaustive list, and too important to risk omitting accidentally from such a list. Special gratitude goes to Lynne Jacobs, who has a unique gift for cultivating my embryonic thoughts, for her generosity with her time. While their contributions have been invaluable, I am solely responsible for the contents of this paper. Introduction When .... therapist's and patient's primary vulnerabilities have been activated and intersect problematically, patient and therapist have become entangled in a relational knot to which both have contributed and from which they cannot extricate themselves. Like a Chinese puzzle, the knot becomes tighter the harder they try to loosen it. They each become dangerous to the other and increasingly defensive. Their perspectives on what is occurring differ and collide.