Riverine Turtles: Fish Or Fowl? Ross Et Al., L99l)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

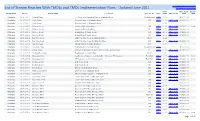

List of TMDL Implementation Plans with Tmdls Organized by Basin

Latest 305(b)/303(d) List of Streams List of Stream Reaches With TMDLs and TMDL Implementation Plans - Updated June 2011 Total Maximum Daily Loadings TMDL TMDL PLAN DELIST BASIN NAME HUC10 REACH NAME LOCATION VIOLATIONS TMDL YEAR TMDL PLAN YEAR YEAR Altamaha 0307010601 Bullard Creek ~0.25 mi u/s Altamaha Road to Altamaha River Bio(sediment) TMDL 2007 09/30/2009 Altamaha 0307010601 Cobb Creek Oconee Creek to Altamaha River DO TMDL 2001 TMDL PLAN 08/31/2003 Altamaha 0307010601 Cobb Creek Oconee Creek to Altamaha River FC 2012 Altamaha 0307010601 Milligan Creek Uvalda to Altamaha River DO TMDL 2001 TMDL PLAN 08/31/2003 2006 Altamaha 0307010601 Milligan Creek Uvalda to Altamaha River FC TMDL 2001 TMDL PLAN 08/31/2003 Altamaha 0307010601 Oconee Creek Headwaters to Cobb Creek DO TMDL 2001 TMDL PLAN 08/31/2003 Altamaha 0307010601 Oconee Creek Headwaters to Cobb Creek FC TMDL 2001 TMDL PLAN 08/31/2003 Altamaha 0307010602 Ten Mile Creek Little Ten Mile Creek to Altamaha River Bio F 2012 Altamaha 0307010602 Ten Mile Creek Little Ten Mile Creek to Altamaha River DO TMDL 2001 TMDL PLAN 08/31/2003 Altamaha 0307010603 Beards Creek Spring Branch to Altamaha River Bio F 2012 Altamaha 0307010603 Five Mile Creek Headwaters to Altamaha River Bio(sediment) TMDL 2007 09/30/2009 Altamaha 0307010603 Goose Creek U/S Rd. S1922(Walton Griffis Rd.) to Little Goose Creek FC TMDL 2001 TMDL PLAN 08/31/2003 Altamaha 0307010603 Mushmelon Creek Headwaters to Delbos Bay Bio F 2012 Altamaha 0307010604 Altamaha River Confluence of Oconee and Ocmulgee Rivers to ITT Rayonier -

Magnitude and Frequency of Rural Floods in the Southeastern United States, 2006: Volume 1, Georgia

Prepared in cooperation with the Georgia Department of Transportation Preconstruction Division Office of Bridge Design Magnitude and Frequency of Rural Floods in the Southeastern United States, 2006: Volume 1, Georgia Scientific Investigations Report 2009–5043 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey Cover: Flint River at North Bridge Road near Lovejoy, Georgia, July 11, 2005. Photograph by Arthur C. Day, U.S. Geological Survey. Magnitude and Frequency of Rural Floods in the Southeastern United States, 2006: Volume 1, Georgia By Anthony J. Gotvald, Toby D. Feaster, and J. Curtis Weaver Prepared in cooperation with the Georgia Department of Transportation Preconstruction Division Office of Bridge Design Scientific Investigations Report 2009–5043 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Department of the Interior KEN SALAZAR, Secretary U.S. Geological Survey Suzette M. Kimball, Acting Director U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, Virginia: 2009 For more information on the USGS--the Federal source for science about the Earth, its natural and living resources, natural hazards, and the environment, visit http://www.usgs.gov or call 1-888-ASK-USGS For an overview of USGS information products, including maps, imagery, and publications, visit http://www.usgs.gov/pubprod To order USGS information products, visit http://store.usgs.gov Any use of trade, product, or firm names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. Although this report is in the public domain, permission must be secured from the individual copyright owners to reproduce any copyrighted materials contained within this report. -

2020 Integrated 305(B)/303(D) List

2020 Integrated 305(b)/303(d) List - Streams Reach Name/ID Reach Location/County River Basin/ Assessment/ Cause/ Size/Unit Category/ Notes Use Data Provider Source Priority Alex Creek Mason Cowpen Branch to Altamaha Not Supporting DO 3 4a TMDL completed DO 2002. Altamaha River GAR030701060503 Wayne Fishing 1,55,10 NP Miles Altamaha River Confluence of Oconee and Altamaha Supporting 72 1 TMDL completed Fish Tissue (Mercury) 2002. Ocmulgee Rivers to ITT Rayonier GAR030701060401 Appling, Wayne, Jeff Davis Fishing 1,55 Miles Altamaha River ITT Rayonier to Altamaha Assessment 20 3 TMDL completed Fish Tissue (Mercury) 2002. More Penholoway Creek Pending data need to be collected and evaluated before it GAR030701060402 Wayne Fishing 10,55 Miles can be determined whether the designated use of Fishing is being met. Altamaha River Penholoway Creek to Altamaha Supporting 27 1 Butler River GAR030701060501 Wayne, Glynn, McIntosh Fishing 1,55 Miles Beards Creek Chapel Creek to Spring Altamaha Not Supporting Bio F 7 4a TMDL completed Bio F 2017. Branch GAR030701060308 Tattnall, Long Fishing 4 NP Miles Beards Creek Spring Branch to Altamaha Not Supporting Bio F 11 4a TMDL completed Bio F in 2012. Altamaha River GAR030701060301 Tattnall Fishing 1,55,10,4 NP, UR Miles Big Cedar Creek Griffith Branch to Little Altamaha Assessment 5 3 This site has a narrative rank of fair for Cedar Creek Pending macroinvertebrates. Waters with a narrative rank GAR030701070108 Washington Fishing 59 Miles of fair will remain in Category 3 until EPD completes the reevaluation of the metrics used to assess macroinvertebrate data. Big Cedar Creek Little Cedar Creek (at Altamaha Not Supporting FC 6 5 EPD needs to determine the "natural DO" for the Donovan Hwy) to Little area before a use assessment is made. -

2018 Integrated 305(B)

2018 Integrated 305(b)/303(d) List - Streams Reach Name/ID Reach Location/County River Basin/ Assessment/ Cause/ Size/Unit Category/ Notes Use Data Provider Source Priority Alex Creek Mason Cowpen Branch to Altamaha Not Supporting DO 3 4a TMDL completed DO 2002. Altamaha River GAR030701060503 Wayne Fishing 1,55,10 NP Miles Altamaha River Confluence of Oconee and Altamaha Supporting 72 1 TMDL completed TWR 2002. Ocmulgee Rivers to ITT Rayonier GAR030701060401 Appling, Wayne, Jeff Davis Fishing 1,55 Miles Altamaha River ITT Rayonier to Penholoway Altamaha Assessment 20 3 TMDL completed TWR 2002. More data need to Creek Pending be collected and evaluated before it can be determined whether the designated use of Fishing is being met. GAR030701060402 Wayne Fishing 10,55 Miles Altamaha River Penholoway Creek to Butler Altamaha Supporting 27 1 River GAR030701060501 Wayne, Glynn, McIntosh Fishing 1,55 Miles Beards Creek Chapel Creek to Spring Branch Altamaha Not Supporting Bio F 7 4a TMDL completed Bio F 2017. GAR030701060308 Tattnall, Long Fishing 4 NP Miles Beards Creek Spring Branch to Altamaha Altamaha Not Supporting Bio F 11 4a TMDL completed Bio F in 2012. River GAR030701060301 Tattnall Fishing 1,55,10,4 NP, UR Miles Big Cedar Creek Griffith Branch to Little Cedar Altamaha Assessment 5 3 This site has a narrative rank of fair for Creek Pending macroinvertebrates. Waters with a narrative rank of fair will remain in Category 3 until EPD completes the reevaluation of the metrics used to assess macroinvertebrate data. GAR030701070108 Washington Fishing 59 Miles Big Cedar Creek Little Cedar Creek to Ohoopee Altamaha Not Supporting DO, FC 3 4a TMDLs completed DO 2002 & FC (2002 & 2007). -

2014 Chapters 3 to 5

CHAPTER 3 establish water use classifications and water quality standards for the waters of the State. Water Quality For each water use classification, water quality Monitoring standards or criteria have been developed, which establish the framework used by the And Assessment Environmental Protection Division to make water use regulatory decisions. All of Georgia’s Background waters are currently classified as fishing, recreation, drinking water, wild river, scenic Water Resources Atlas The river miles and river, or coastal fishing. Table 3-2 provides a lake acreage estimates are based on the U.S. summary of water use classifications and Geological Survey (USGS) 1:100,000 Digital criteria for each use. Georgia’s rules and Line Graph (DLG), which provides a national regulations protect all waters for the use of database of hydrologic traces. The DLG in primary contact recreation by having a fecal coordination with the USEPA River Reach File coliform bacteria standard of a geometric provides a consistent computerized mean of 200 per 100 ml for all waters with the methodology for summing river miles and lake use designations of fishing or drinking water to acreage. The 1:100,000 scale map series is apply during the months of May - October (the the most detailed scale available nationally in recreational season). digital form and includes 75 to 90 percent of the hydrologic features on the USGS 1:24,000 TABLE 3-1. WATER RESOURCES ATLAS scale topographic map series. Included in river State Population (2006 Estimate) 9,383,941 mile estimates are perennial streams State Surface Area 57,906 sq.mi. -

Moving Georgia Forward: Road and Bridge Conditions, Traffic Safety, Travel Trends

Moving Georgia Forward: Road and Bridge Conditions, Traffic Safety, Travel Trends and Funding Needs in Georgia NOVEMBER 2020 Founded in 1971, TRIP® of Washington, DC, is a nonprofit organization that researches, evaluates and distributes economic and technical data on surface transportation issues. TRIP is sponsored by insurance companies, equipment manufacturers, distributors and suppliers; businesses involved in highway and transit engineering and construction; labor unions; and organizations concerned with efficient and safe surface transportation. Moving Georgia Forward Introduction Accessibility and connectivity are critical factors in a region or state’s quality of life and economic competitiveness. The growth and development of a region hinges on the ability of people and businesses to efficiently and safety access employment, customers, commerce, recreation, education and healthcare via multiple transportation modes. The quality of life of residents in Georgia and the pace of the state’s economic growth are directly tied to the condition, efficiency, safety and resiliency of the state’s transportation system. The necessity of a reliable transportation system in Georgia has been reinforced during the coronavirus pandemic, which has placed increased importance on the ability of a region’s transportation network to support a reliable supply chain. Providing a safe, efficient and well-maintained 21st century transportation system, which will require long-term, sustainable funding, is critical to supporting economic growth, improved safety and quality of life throughout the area. A lack of reliable and adequate transportation funding could jeopardize the condition, efficiency and connectivity of the region’s transportation network and hamper economic growth. TRIP’s “Moving Georgia Forward” report examines travel and population trends, road and bridge conditions, traffic safety, congestion, and transportation funding needs in Georgia. -

Total Maximum Daily Load Evaluation for Three Segments in the Suwannee River Basin for Lead

Total Maximum Daily Load Evaluation for Three Segments in the Suwannee River Basin for Lead Submitted to: The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Region 4 Atlanta, Georgia Submitted by: The Georgia Department of Natural Resources Environmental Protection Division Atlanta, Georgia April 2017 Total Maximum Daily Load Evaluation April 2017 Suwannee River Basin (Lead) Table of Contents Section Page EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ........................................................................................................... iv 1.0 INTRODUCTION.................................................................................................................. 1 1.1 Background.................................................................................................................. 1 1.2 Watershed Description ................................................................................................. 1 1.3 Regional Water Planning Councils ............................................................................... 2 1.4 Water Quality Standards .............................................................................................. 2 1.5 Background Information for Lead ................................................................................. 8 2.0 WATER QUALITY ASSESSMENT ..................................................................................... 9 3.0 SOURCE ASSESSMENT ...................................................................................................11 3.1 Point Source Assessment ...........................................................................................11 -

Dissolved Oxygen TMDL Report

Suwannee River Basin Dissolved Oxygen TMDL Submittals Submitted to: U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Region 4 Atlanta, Georgia Submitted by: Georgia Department of Natural Resources Environmental Protection Department Atlanta, Georgia December 2001 Suwannee River Basin Dissolved Oxygen TMDLs Ochlockonee Rive Finalr Table of Contents Section Title Page TMDL Executive Summary ...................................................................................... 3 1.0 Introduction ...............................................................................................................7 2.0 Problem Understanding............................................................................................. 8 3.0 Water Quality Standards.......................................................................................... 12 4.0 Source Assessment .................................................................................................. 13 5.0 Summary of Technical Approach............................................................................ 18 6.0 Loading Capacity..................................................................................................... 33 7.0 Waste Load and Load Allocations........................................................................... 35 8.0 Margin of Safety...................................................................................................... 35 9.0 Seasonal Variation.................................................................................................. -

List of Rivers of Georgia

Sl. No River Name Draining Into 1 Savannah River Atlantic Ocean 2 Black Creek Atlantic Ocean 3 Knoxboro Creek Atlantic Ocean 4 Ebenezer Creek Atlantic Ocean 5 Brier Creek Atlantic Ocean 6 Little River Atlantic Ocean 7 Kettle Creek Atlantic Ocean 8 Broad River Atlantic Ocean 9 Hudson River Atlantic Ocean 10 Tugaloo River Atlantic Ocean 11 Chattooga River Atlantic Ocean 12 Tallulah River Atlantic Ocean 13 Coleman River Atlantic Ocean 14 Bull River Atlantic Ocean 15 Shad River Atlantic Ocean 16 Halfmoon River Atlantic Ocean 17 Wilmington River Atlantic Ocean 18 Skidaway River Atlantic Ocean 19 Herb River Atlantic Ocean 20 Odingsell River Atlantic Ocean 21 Ogeechee River Atlantic Ocean 22 Little Ogeechee River (Chatham County) Atlantic Ocean 23 Vernon River Atlantic Ocean 24 Canoochee River Atlantic Ocean 25 Williamson Swamp Creek Atlantic Ocean 26 Rocky Comfort Creek Atlantic Ocean 27 Little Ogeechee River (Hancock County) Atlantic Ocean 28 Bear River Atlantic Ocean 29 Medway River Atlantic Ocean 30 Belfast River Atlantic Ocean 31 Tivoli River Atlantic Ocean 32 Laurel View River Atlantic Ocean 33 Jerico River Atlantic Ocean 34 North Newport River Atlantic Ocean 35 South Newport River Atlantic Ocean 36 Sapelo River Atlantic Ocean 37 Broro River Atlantic Ocean 38 Mud River Atlantic Ocean 39 Crescent River Atlantic Ocean 40 Duplin River Atlantic Ocean 41 North River Atlantic Ocean 42 South River Atlantic Ocean 43 Darien River Atlantic Ocean 44 Altamaha River Atlantic Ocean 45 Ohoopee River Atlantic Ocean 46 Little Ohoopee River Atlantic Ocean -

The Effect of Nutrient Enrichment on Stream Periphyton Growth In

THE EFFECT OF NUTRIENT ENRICHMENT ON STREAM PERIPHYTON GROWTH IN THE SOUTHERN COASTAL PLAIN OF GEORGIA: IMPLICATIONS FOR LOW DISSOLVED OXYGEN by RICHARD CAREY (Under the Direction of Catherine Pringle and George Vellidis) ABSTRACT Blackwater rivers are common throughout the Atlantic Coastal Plain and water quality is heavily influenced by the flat topography, sandy soils and floodplain swamp forests. In the southern coastal plain of Georgia, streams regularly violate dissolved oxygen (DO) standards established by the Georgia Department of Natural Resources. Total Maximum Daily Load (TMDL) management plans must be developed for watersheds that are drained by DO-impaired streams but previous studies suggest DO may be naturally low. At nine sites throughout the region, eighteen passive nutrient diffusion periphytometers were deployed to determine if algal growth was nutrient and/or light limited. Periphyton biomass for treatments in the sun, measured as chlorophyll a, was significantly (p < 0.05) greater than corresponding treatments in the shade and algal growth was nutrient-limited at several sites where DO concentrations were below regulatory standards. Factors other than algae may be responsible for low DO concentrations during summer. INDEX WORDS: Periphyton, Periphytometer, Dissolved Oxygen, Nutrient Enrichment THE EFFECT OF NUTRIENT ENRICHMENT ON STREAM PERIPHYTON GROWTH IN THE SOUTHERN COASTAL PLAIN OF GEORGIA: IMPLICATIONS FOR LOW DISSOLVED OXYGEN by RICHARD CAREY B.S., University of Miami, 2001 A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate -

Georgia Water Quality

GEORGIA SURFACE WATER AND GROUNDWATER QUALITY MONITORING AND ASSESSMENT STRATEGY Okefenokee Swamp, Georgia PHOTO: Kathy Methier Georgia Department of Natural Resources Environmental Protection Division Watershed Protection Branch 2 Martin Luther King Jr. Drive Suite 1152, East Tower Atlanta, GA 30334 GEORGIA SURFACE WATER AND GROUND WATER QUALITY MONITORING AND ASSESSMENT STRATEGY 2015 Update PREFACE The Georgia Environmental Protection Division (GAEPD) of the Department of Natural Resources (DNR) developed this document entitled “Georgia Surface Water and Groundwater Quality Monitoring and Assessment Strategy”. As a part of the State’s Water Quality Management Program, this report focuses on the GAEPD’s water quality monitoring efforts to address key elements identified by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (USEPA) monitoring strategy guidance entitled “Elements of a State Monitoring and Assessment Program, March 2003”. This report updates the State’s water quality monitoring strategy as required by the USEPA’s regulations addressing water management plans of the Clean Water Act, Section 106(e)(1). Georgia Department of Natural Resources Environmental Protection Division Watershed Protection Branch 2 Martin Luther King Jr. Drive Suite 1152, East Tower Atlanta, GA 30334 GEORGIA SURFACE WATER AND GROUND WATER QUALITY MONITORING AND ASSESSMENT STRATEGY 2015 Update TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS .............................................................................................. 1 INTRODUCTION......................................................................................................... -

Do Nutrients Limit Algal Periphyton in Small Blackwater Coastal Plain Streams?1

JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN WATER RESOURCES ASSOCIATION Vol. 43, No. 5 AMERICAN WATER RESOURCES ASSOCIATION October 2007 DO NUTRIENTS LIMIT ALGAL PERIPHYTON IN SMALL BLACKWATER COASTAL PLAIN STREAMS?1 Richard O. Carey, George Vellidis, Richard Lowrance, and Catherine M. Pringle2 ABSTRACT: We examine the potential for nutrient limitation of algal periphyton biomass in blackwater streams draining the Georgia coastal plain. Previous studies have investigated nutrient limitation of planktonic algae in large blackwater rivers, but virtually no scientific information exists regarding how algal periphyton respond to nutrients under different light conditions in smaller, low-flow streams. We used a modification of the Matlock periphytometer (nutrient-diffusing substrata) to determine if algal growth was nutrient limited and ⁄ or light limited at nine sites spanning a range of human impacts from relatively undisturbed forested basins to highly disturbed agricultural sites. We employed four treatments in both shaded and sunny conditions at each site: (1) control, (2) N (NO3-N), (3) P (PO4-P), and (4) N + P (NO3-N + PO4-P). Chlorophyll a response was measured on 10 replicate substrates per treatment, after 15 days of in situ exposure. Chlorophyll a values did not approach what have been defined as nuisance levels (i.e., 100-200 mg ⁄ m2), even in response to nutrient enrich- ment in sunny conditions. For Georgia coastal plain streams, algal periphyton growth appears to be primarily light limited and can be secondarily nutrient limited (most commonly by P or N + P combined) in light gaps and ⁄ or open areas receiving sunlight. (KEY TERMS: algae; periphyton; periphytometer; nutrient limitation; light limitation; water quality.) Carey, Richard O., George Vellidis, Richard Lowrance, and Catherine M.