Reassessing the Visual Networks of Barlaam and Ioasaph

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Our Holy Father RAPHAEL Was Born in Syria in 1860 to Pious Orthodox Parents, Michael Hawaweeny and His Second Wife Mariam

In March of 1907 Saint TIKHON returned to Russia and was replaced by From his youth, Saint RAPHAEL's greatest joy was to serve the Church. When Archbishop PLATON. Once again Saint RAPHAEL was considered for episcopal he came to America, he found his people scattered abroad, and he called them to office in Syria, being nominated to succeed Patriarch GREGORY as Metropolitan of unity. Tripoli in 1908. The Holy Synod of Antioch removed Bishop RAPHAEL's name from He never neglected his flock, traveling throughout America, Canada, and the list of candidates, citing various canons which forbid a bishop being transferred Mexico in search of them so that he might care for them. He kept them from from one city to another. straying into strange pastures and spiritual harm. During 20 years of faithful On the Sunday of Orthodoxy in 1911, Bishop RAPHAEL was honored for his 15 ministry, he nurtured them and helped them to grow. years of pastoral ministry in America. Archbishop PLATON presented him with a At the time of his death, the Syro-Arab Mission had 30 parishes with more silver-covered icon of Christ and praised him for his work. In his humility, Bishop than 25,000 faithful. The Self-Ruled Antiochian Orthodox Christian Archdiocese of RAPHAEL could not understand why he should be honored merely for doing his duty North America now has more than 240 U.S. and Canadian parishes. (Luke 17:10). He considered himself an "unworthy servant," yet he did perfectly Saint RAPHAEL also was a scholar and the author of several books. -

Domitian's Arae Incendii Neroniani in New Flavian Rome

Rising from the Ashes: Domitian’s Arae Incendii Neroniani in New Flavian Rome Lea K. Cline In the August 1888 edition of the Notizie degli Scavi, profes- on a base of two steps; it is a long, solid rectangle, 6.25 m sors Guliermo Gatti and Rodolfo Lanciani announced the deep, 3.25 m wide, and 1.26 m high (lacking its crown). rediscovery of a Domitianic altar on the Quirinal hill during These dimensions make it the second largest public altar to the construction of the Casa Reale (Figures 1 and 2).1 This survive in the ancient capital. Built of travertine and revet- altar, found in situ on the southeast side of the Alta Semita ted in marble, this altar lacks sculptural decoration. Only its (an important northern thoroughfare) adjacent to the church inscription identifies it as an Ara Incendii Neroniani, an altar of San Andrea al Quirinale, was not unknown to scholars.2 erected in fulfillment of a vow made after the great fire of The site was discovered, but not excavated, in 1644 when Nero (A.D. 64).7 Pope Urban VIII (Maffeo Barberini) and Gianlorenzo Bernini Archaeological evidence attests to two other altars, laid the foundations of San Andrea al Quirinale; at that time, bearing identical inscriptions, excavated in the sixteenth the inscription was removed to the Vatican, and then the and seventeenth centuries; the Ara Incendii Neroniani found altar was essentially forgotten.3 Lanciani’s notes from May on the Quirinal was the last of the three to be discovered.8 22, 1889, describe a fairly intact structure—a travertine block Little is known of the two other altars; one, presumably altar with remnants of a marble base molding on two sides.4 found on the Vatican plain, was reportedly used as building Although the altar’s inscription was not in situ, Lanciani refers material for the basilica of St. -

Volume 61 No. 9 December 2017 VOLUME 61 NO

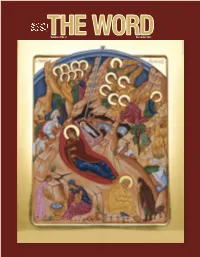

Volume 61 No. 9 December 2017 VOLUME 61 NO. 9 DECEMBER 2017 COVER: ICON OF THE NATIVITY EDITORIAL Handwritten icon by Khourieh Randa Al Khoury Azar Using old traditional technique contents [email protected] 3 EDITORIAL CELEBRATING CHRISTMAS by Bishop JOHN 5 PLEADING FOR THE LIVES OF THE DEFINES US PEOPLE OF THE MIDDLE EAST: THE U.S. VISIT OF HIS BEATITUDE PATRIARCH JOHN X OF ANTIOCH EVERYONE SEEMS TO BE TALKING ABOUT IDENTITY THESE DAYS. IT’S NOT JUST AND ALL THE EAST by Sub-deacon Peter Samore ADOLESCENTS WHO ARE ASKING THE FUNDAMENTAL QUESTION, “WHO AM I?” RATHER, and Sonia Chala Tower THE QUESTION OF WHAT IT IS TO BE HUMAN IS RAISED IMPLICITLY BY MANY. WHILE 8 PASTORAL LETTER OF HIS EMINENCE METROPOLITAN JOSEPH PHILOSOPHERS AND PSYCHOLOGISTS HAVE ADDRESSED THIS QUESTION OF HUMAN 9 I WOULD FLY AWAY AND BE AT REST: IDENTITY OVER THE YEARS, GOD ANSWERED IT WHEN THE WORD BECAME FLESH AND THE LAST PUBLIC APPEARANCE AND FUNERAL OF DWELT AMONG US. HE TOOK ON OUR FLESH SO THAT WE MAY PARTICIPATE IN HIS HIS GRACE BISHOP ANTOUN DIVINITY. CHRIST REVEALED TO US WHO GOD IS AND WHO WE ARE TO BE. WE ARE CALLED by Sub-deacon Peter Samore 10 THE GHOST OF PAST CHRISTIANS BECAUSE HE HAS MADE US AS LITTLE CHRISTS BY ACCEPTING US IN BAPTISM CHRISTMAS PRESENTS AND SHARING HIMSELF IN US. JUST AS CHRIST REVEALS THE FATHER, SO WE ARE TO by Fr. Joseph Huneycutt 13 RUMINATION: ARE WE CREATING REVEAL HIM. JUST AS CHRIST IS THE INCARNATION OF GOD, JOINED TO GOD WE SHOW HIM OLD TESTAMENT CHRISTIANS? TO THE WORLD. -

The Protrepticus of Clement of Alexandria: a Commentary

Miguel Herrero de Jáuregui THE PROTREPTICUS OF CLEMENT OF ALEXANDRIA: A COMMENTARY to; ga;r yeu'do" ouj yilh'/ th'/ paraqevsei tajlhqou'" diaskedavnnutai, th'/ de; crhvsei th'" ajlhqeiva" ejkbiazovmenon fugadeuvetai. La falsedad no se dispersa por la simple comparación con la verdad, sino que la práctica de la verdad la fuerza a huir. Protréptico 8.77.3 PREFACIO Una tesis doctoral debe tratar de contribuir al avance del conocimiento humano en su disciplina, y la pretensión de que este comentario al Protréptico tenga la máxima utilidad posible me obliga a escribirla en inglés porque es la única lengua que hoy casi todos los interesados pueden leer. Pero no deja de ser extraño que en la casa de Nebrija se deje de lado la lengua castellana. La deuda que contraigo ahora con el español sólo se paliará si en el futuro puedo, en compensación, “dar a los hombres de mi lengua obras en que mejor puedan emplear su ocio”. Empiezo ahora a saldarla, empleándola para estos agradecimientos, breves en extensión pero no en sinceridad. Mi gratitud va, en primer lugar, al Cardenal Don Gil Álvarez de Albornoz, fundador del Real Colegio de España, a cuya generosidad y previsión debo dos años provechosos y felices en Bolonia. Al Rector, José Guillermo García-Valdecasas, que administra la herencia de Albornoz con ejemplar dedicación, eficacia y amor a la casa. A todas las personas que trabajan en el Colegio y hacen que cumpla con creces los objetivos para los que se fundó. Y a mis compañeros bolonios durante estos dos años. Ha sido un honor muy grato disfrutar con todos ellos de la herencia albornociana. -

Eight Unedited Poems to His Friends and Patrons by Manuel Philes

DOI 10.1515/bz-2020-0038 BZ 2020; 113(3): 879–904 Krystina Kubina Eight unedited poems to hisfriends and patrons by Manuel Philes Abstract: This article presents the critical edition of eight hitherto unpublished poems by Manuel Philes together with atranslation and acommentary.The poems are verse letters addressed to various high-rankingindividuals. Poem 1 is addressed to the emperor,whose power is emphasised in arequest to help Philes escape from his misery.Poem 2isafragment likewise addressed to the emperor.Poem 3isaconsolatory poem for afather whose son has died.In poem 4, Philes addresses apatron whose wife hurried to Constantinople after she had become the object of hostility of unknown people. Poem 5isaddressed to the month of August and deals with the return of abenefactor of Philes to Con- stantinople. In poem 6, Philes writes on behalf of an unnamed banker and asks the megas dioiketes Kabasilastojudge the latter justly. Poems 7and 8are tetra- sticha includingarequestfor wine. Adresse: Dr.KrystinaKubina, Österreichische Akademie der Wissenschaften, Institut für Mittelalterforschung,AbteilungByzanzforschung,Hollandstraße 11–13, A-1020 Wien; [email protected] Manuel Philes (c. 1270–after 1332)suffers from aparadoxical fate. Philes was the most important and most prolific poet of the final 300 years of the Byzantine em- pire; yetthe greater part of his oeuvrestill languishes in outdated and uncritical editions from the 19th century.¹ There are even some poems that are still unedited Idearly thankAndreas Rhoby, MarcLauxtermann and Nathanael Aschenbrenner fortheir com- ments on earlier drafts of thispaper.Iam also grateful to ZacharyRothstein-Dowden whose help withmyEnglish translations by far exceeded alanguageproof.They all saved me from some blatant errors.Mythanksare extended to the two anonymous reviewerswhose sugges- tions greatly improved the quality of thispaper.Itgoeswithout saying that all remaining mis- takesare my own. -

Constantinople: Capital of Byzantium'

H-War Brown on Harris, 'Constantinople: Capital of Byzantium' Review published on Thursday, November 19, 2020 Jonathan Harris. Constantinople: Capital of Byzantium. New York: Bloomsbury Academic, 2017. ix + 288 pp. $29.95 (paper), ISBN 978-1-4742-5464-9. Reviewed by Amelia Brown (University of Queensland) Published on H-War (November, 2020) Commissioned by Margaret Sankey (Air University) Printable Version: https://www.h-net.org/reviews/showpdf.php?id=53285 Jonathan Harris’s Constantinople: Capital of Byzantium is a good general introduction to the history of this important medieval city. It is aimed at students but is also suitable for the general reader who wants to know more about Constantinople’s history, monuments, and significance. Eight chapters illuminate the city thematically from its fourth-century refoundation through its twelfth-century heyday. Another four chapters cover “The Latin interlude” and the city after the Crusader sack of 1204 up to “today” in a briefer way. There follow appendices (a time line and list of emperors), endnotes with primary and secondary citations in author-date format, a further reading list (books and online), a bibliography of primary and secondary sources, and an index. Twelve brief text boxes, four maps, and twenty small black-and-white illustrations are scattered unevenly throughout the book. This is a revised and expanded version of a 2007 first edition. Harris does not assume knowledge of Greek language, Byzantine history, or modern Istanbul but gives a coherent and accessible introduction to Constantinople. A summary of the chapters and a note on a few typographical errors are given in this review. -

Vespasian's Apotheosis

VESPASIAN’S APOTHEOSIS Andrew B. Gallia* In the study of the divinization of Roman emperors, a great deal depends upon the sequence of events. According to the model of consecratio proposed by Bickermann, apotheosis was supposed to be accomplished during the deceased emperor’s public funeral, after which the senate acknowledged what had transpired by decreeing appropriate honours for the new divus.1 Contradictory evidence has turned up in the Fasti Ostienses, however, which seem to indicate that both Marciana and Faustina were declared divae before their funerals took place.2 This suggests a shift * Published in The Classical Quarterly 69.1 (2019). 1 E. Bickermann, ‘Die römische Kaiserapotheosie’, in A. Wlosok (ed.), Römischer Kaiserkult (Darmstadt, 1978), 82-121, at 100-106 (= Archiv für ReligionswissenschaftW 27 [1929], 1-31, at 15-19); id., ‘Consecratio’, in W. den Boer (ed.), Le culte des souverains dans l’empire romain. Entretiens Hardt 19 (Geneva, 1973), 1-37, at 13-25. 2 L. Vidman, Fasti Ostienses (Prague, 19822), 48 J 39-43: IIII k. Septembr. | [Marciana Aug]usta excessit divaq(ue) cognominata. | [Eodem die Mati]dia Augusta cognominata. III | [non. Sept. Marc]iana Augusta funere censorio | [elata est.], 49 O 11-14: X[— k. Nov. Fausti]na Aug[usta excessit eodemq(ue) die a] | senatu diva app[ellata et s(enatus) c(onsultum) fact]um fun[ere censorio eam efferendam.] | Ludi et circenses [delati sunt. — i]dus N[ov. Faustina Augusta funere] | censorio elata e[st]. Against this interpretation of the Marciana fragment (as published by A. Degrassi, Inscr. It. 13.1 [1947], 201) see E. -

Postcolonial Syria and Lebanon

Post-colonial Syria and Lebanon POST-COLONIAL SYRIA AND LEBANON THE DECLINE OF ARAB NATIONALISM AND THE TRIUMPH OF THE STATE Youssef Chaitani Published in 2007 by I.B.Tauris & Co Ltd 6 Salem Road, London W2 4BU 175 Fifth Avenue, New York NY 10010 www.ibtauris.com In the United States and Canada distributed by Palgrave Macmillan, a division of St. Martin’s Press, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York NY 10010 Copyright © Youssef Chaitani, 2007 The right of Youssef Chaitani to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations in a review, this book, or any part thereof, may not be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher. The views expressed herein are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the United Nations. ISBN: 978 1 84511 294 3 Library of Middle East History 11 A full CIP record for this book is available from the British Library A full CIP record for this book is available from the Library of Congress Library of Congress catalog card: available Typeset in Minion by Dexter Haven Associates Ltd, London Printed and bound in India by Replika Press Pvt. Ltd CONTENTS Acknowledgements vii Foreword ix Introduction 1 1The Syrian Arab Nationalists: Independence First 14 A. The Forging of a New Alliance 14 B. -

The Mediaeval Bestiary and Its Textual Tradition

THE MEDIAEVAL BESTIARY AND ITS TEXTUAL TRADITION Volume 1: Text Patricia Stewart A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD at the University of St Andrews 2012 Full metadata for this item is available in St Andrews Research Repository at: http://research-repository.st-andrews.ac.uk/ Please use this identifier to cite or link to this item: http://hdl.handle.net/10023/3628 This item is protected by original copyright The Mediaeval Bestiary and its Textual Tradition Patricia Stewart This thesis is submitted in partial fulfilment for the degree of PhD at the University of St Andrews 17th August, 2012 1. Candidate’s declarations: I, Patricia Stewart, hereby certify that this thesis, which is approximately 88 000 words in length, has been written by me, that it is the record of work carried out by me and that it has not been submitted in any previous application for a higher degree. I was admitted as a research student in September, 2007 and as a candidate for the degree of PhD in May, 2008; the higher study for which this is a record was carried out in the University of St Andrews between 2007 and 2012. Date 17th August, 2012 signature of candidate ……… 2. Supervisor’s declaration: I hereby certify that the candidate has fulfilled the conditions of the Resolution and Regulations appropriate for the degree of PhD in the University of St Andrews and that the candidate is qualified to submit this thesis in application for that degree. Date 17th August, 2012 signature of supervisor ……… 3. Permission for electronic publication: (to be signed by both candidate and supervisor) In submitting this thesis to the University of St Andrews I understand that I am giving permission for it to be made available for use in accordance with the regulations of the University Library for the time being in force, subject to any copyright vested in the work not being affected thereby. -

Tiberius Nero Caesar (Tiberius) - the Lives of the Twelve Caesars, Volume 3

Tiberius Nero Caesar (Tiberius) - The Lives Of The Twelve Caesars, Volume 3. C. Suetonius Tranquillus Project Gutenberg's Tiberius Nero Caesar (Tiberius), by C. Suetonius Tranquillus This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.net Title: Tiberius Nero Caesar (Tiberius) The Lives Of The Twelve Caesars, Volume 3. Author: C. Suetonius Tranquillus Release Date: December 13, 2004 [EBook #6388] Language: English Character set encoding: ASCII *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK TIBERIUS NERO CAESAR *** Produced by Tapio Riikonen and David Widger THE LIVES OF THE TWELVE CAESARS By C. Suetonius Tranquillus; To which are added, HIS LIVES OF THE GRAMMARIANS, RHETORICIANS, AND POETS. The Translation of Alexander Thomson, M.D. revised and corrected by T.Forester, Esq., A.M. Livros Grátis http://www.livrosgratis.com.br Milhares de livros grátis para download. TIBERIUS NERO CAESAR. (192) I. The patrician family of the Claudii (for there was a plebeian family of the same name, no way inferior to the other either in power or dignity) came originally from Regilli, a town of the Sabines. They removed thence to Rome soon after the building of the city, with a great body of their dependants, under Titus Tatius, who reigned jointly with Romulus in the kingdom; or, perhaps, what is related upon better authority, under Atta Claudius, the head of the family, who was admitted by the senate into the patrician order six years after the expulsion of the Tarquins. -

An Account of the Μυρµηκολέων Or Ant-Lion

An account of the Μυρµηκολέων or Ant-lion By GEORGE C. DRUCE, F.S.A. Originally published in The Antiquaries Journal (Society of Antiquaries of London) Volume III, Number 4, October 1923 Pages 347-364 Version 2 August 2004 Introduction to the Digital Edition This text was prepared for digital publication by David Badke in October, 2003. It was scanned from the original text. Version 2, with corrected Druce biography, was produced in August, 2004. Author: George Claridge Druce was born in Surrey, England and lived there and at Wimbledon until 1923, when he retired from managing a distillery company and moved to Cranbrook, Kent. He was a member of the Kent Archaeological Society from 1909, as Secretary from 1925 to 1935 and then Vice-President until his death. He was a member of the Royal Archaeological Institute (1903-48, Council member 1921-28) and of the British Archaeological Association, joining in 1920, serving on its Council 1921-38 and then as Vice President (1938-48). He was elected a Fellow of the Society of Antiquaries (F.S.A.) of London in 1912 and served on its Council 1923-6. Druce travelled extensively (by bicycle) with his camera, and built up a unique collection of photographs and glass lantern slides, which in 1947 he presented to the Courtauld Institute in London. Although interested in almost all branches of antiquarian study, he specialized in the study of the bestiary genre, and was widely recognized as an authority on the influence of bestiaries on ecclesiastical sculpture and wood carving. He also studied manuscripts both in England and elsewhere. -

Durham E-Theses

Durham E-Theses Methodios I patriarch of Constantinople: churchman, politician and confessor for the faith Bithos, George P. How to cite: Bithos, George P. (2001) Methodios I patriarch of Constantinople: churchman, politician and confessor for the faith, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/4239/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk 2 METHODIOS I PATRIARCH OF CONSTANTINOPLE Churchman, Politician and Confessor for the Faith Submitted by George P. Bithos BS DDS University of Durham Department of Theology A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Orthodox Theology and Byzantine History 2001 The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. No quotation from it should be published in any form, including' Electronic and the Internet, without the author's prior written consent All information derived from this thesis must be acknowledged appropriately.