Perth's Regional Parks – Providing for Biodiversity Conservation and Public

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

WABN #171 2019 Sep.Pdf

Western Australian Bird Notes Quarterly Newsletter of the Western Australian Branch of BirdLife Australia No. 171 September 2019 birds are in our nature Members in the field Western Australian Branch of EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE, 2019 BirdLife Australia Office: Peregrine House Chair: Mr Viv Read 167 Perry Lakes Drive, Floreat WA 6014 Vice Chair: Dr Mike Bamford Hours: Monday-Friday 9:30 am to 12.30 pm Telephone: (08) 9383 7749 Secretary: Lou Scampoli E-mail: [email protected] Treasurer: Beverly Winterton BirdLife WA web page: www.birdlife.org.au/wa Chair: Mr Viv Read Committee: Alasdair Bulloch, Max Goodwin, Mark Henryon, Andrew Hobbs, Jennifer Sumpton and one vacancy (due to BirdLife Western Australia is the WA Branch of the national resignation of Plaxy Barratt) organisation, BirdLife Australia. We are dedicated to creating a brighter future for Australian birds. General meetings: Held at the Bold Park Eco Centre, Perry Lakes Drive, Floreat, commencing 7:30 pm on the 4th Monday of the month (except December) – see ‘Coming events’ for details. Executive meetings: Held at Peregrine House on the 2nd Grey-crowned Babbler with slater at Emu Creek Monday of the month. Communicate any Station, by Ian Wallace matters for consideration to the Chair. Western Australian Bird Notes Red-backed Kingfisher in Margaret River. Photo by Print ISSN 1445-3983 Online ISSN 2206-8716 Christine Wilder Joint WABN Editors: Allan Burbidge Tel: (08) 9405 5109 (w) Tel/Fax: (08) 9306 1642 (h) Fax: (08) 9306 1641 (w) E-mail: [email protected] Suzanne Mather Tel: (08) 9389 6416 E-mail: [email protected] Production: Michelle Crow Printing and distribution: Daniels Printing Craftsmen Tel: (08) 9204 6800 danielspc.com.au Notes for Contributors The Editors request contributors to note: • WABN publishes material of interest to the WA Branch; Brown-headed Honeyeater at Lesmurdie. -

A Snapshot of Contaminants in Drains of Perth's Industrial Areas

Government of Western Australia Department of Water A snapshot of contaminants in drains of Perth’s industrial areas Industrial contaminants in stormwater of Herdsman Lake, Bayswater Drain, Bickley Brook and Bibra Lake between October 2007 and January 2008 Looking after all our water needs Water technicalScience series Report no. WST 12 April 2009 A snapshot of contaminants in drains of Perth’s industrial areas Industrial contaminants in stormwater of Herdsman Lake, Bayswater Drain, Bickley Brook and Bibra Lake between October 2007 and January 2008 Department of Water Water Science technical series Report No.12 April 2009 Department of Water 168 St Georges Terrace Perth Western Australia 6000 Telephone +61 8 6364 7600 Facsimile +61 8 6364 7601 www.water.wa.gov.au © Government of Western Australia 2008 April 2009 This work is copyright. You may download, display, print and reproduce this material in unaltered form only (retaining this notice) for your personal, non-commercial use or use within your organisation. Apart from any use as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, all other rights are reserved. Requests and inquiries concerning reproduction and rights should be addressed to the Department of Water. ISSN 1836-2869 (print) ISSN 1836-2877 (online) ISBN 978-1-921637-10-0 (print) ISBN 978-1-921637-11-7 (online) Acknowledgements This project was funded by the Australian Government through the Perth Region NRM (formerly the Swan Catchment Council). This report was prepared by George Foulsham with assistance from a number of staff in the Water Science Branch of the Department of Water. Sarah Evans provided support in the field with all the water and sediment collection. -

82452 JW.Rdo

Item 9.1.19 Item 9.1.19 Item 9.1.19 Item 9.1.19 Item 9.1.19 Item 9.1.19 Item 9.1.19 Item 9.1.19 WSD Item 9.1.19 H PP TONKIN HS HS HWY SU PICKERING BROOK HS ROE HS TS CANNING HILLS HS HWY MARTIN HS HS SU HS GOSNELLS 5 8 KARRAGULLEN HWY RANFORD HS P SOUTHERN 9 RIVER HS 11 BROOKTON SU 3 ROAD TS 12 H ROLEYSTONE 10 ARMADALE HWY 13 HS ROAD 4 WSD ARMADALE 7 6 FORRESTDALE HS 1 ALBANY 2 ILLAWARRA WESTERN BEDFORDALE HIGHWAY WSD THOMAS ROAD OAKFORD SOUTH WSD KARRAKUP OLDBURY SU Location of the proposed amendment to the MRS for 1161/41 - Parks and Recreation Amendment City of Armadale METROPOLITAN REGION SCHEME LEGEND Proposed: RESERVED LANDS ZONES PARKS AND RECREATION PUBLIC PURPOSES - URBAN Parks and Recreation Amendment 1161/41 DENOTED AS FOLLOWS : 1 R RESTRICTED PUBLIC ACCESS URBAN DEFERRED City of Armadale H HOSPITAL RAILWAYS HS HIGH SCHOOL CENTRAL CITY AREA TS TECHNICAL SCHOOL PORT INSTALLATIONS INDUSTRIAL CP CAR PARK U UNIVERSITY STATE FORESTS SPECIAL INDUSTRIAL CG COMMONWEALTH GOVERNMENT WATER CATCHMENTS SEC STATE ENERGY COMMISSION RURAL SU SPECIAL USES CIVIC AND CULTURAL WSD WATER AUTHORITY OF WA PRIVATE RECREATION P PRISON WATERWAYS RURAL - WATER PROTECTION ROADS : PRIMARY REGIONAL ROADS METROPOLITAN REGION SCHEME BOUNDARY OTHER REGIONAL ROADS armadaleloc.fig N 26 Mar 2009 Produced by Mapping & GeoSpatial Data Branch, Department for Planning and Infrastructure Scale 1:150 000 On behalf of the Western Australian Planning Commission, Perth WA 0 4 Base information supplied by Western Australian Land Information Authority GL248-2007-2 GEOCENTRIC -

Swamp : Walking the Wetlands of the Swan Coastal Plain

Edith Cowan University Research Online Theses: Doctorates and Masters Theses 2012 Swamp : walking the wetlands of the Swan Coastal Plain ; and with the exegesis, A walk in the anthropocene: homesickness and the walker-writer Anandashila Saraswati Edith Cowan University Recommended Citation Saraswati, A. (2012). Swamp : walking the wetlands of the Swan Coastal Plain ; and with the exegesis, A walk in the anthropocene: homesickness and the walker-writer. Retrieved from https://ro.ecu.edu.au/theses/588 This Thesis is posted at Research Online. https://ro.ecu.edu.au/theses/588 Edith Cowan University Copyright Warning You may print or download ONE copy of this document for the purpose of your own research or study. The University does not authorize you to copy, communicate or otherwise make available electronically to any other person any copyright material contained on this site. You are reminded of the following: Copyright owners are entitled to take legal action against persons who infringe their copyright. A reproduction of material that is protected by copyright may be a copyright infringement. A court may impose penalties and award damages in relation to offences and infringements relating to copyright material. Higher penalties may apply, and higher damages may be awarded, for offences and infringements involving the conversion of material into digital or electronic form. USE OF THESIS This copy is the property of Edith Cowan University. However, the literary rights of the author must also be respected. If any passage from this thesis is quoted or closely paraphrased in a paper of written work prepared by the user, the source of the passage must be acknowledged in the work. -

Nyungar Tradition

Nyungar Tradition : glimpses of Aborigines of south-western Australia 1829-1914 by Lois Tilbrook Background notice about the digital version of this publication: Nyungar Tradition was published in 1983 and is no longer in print. In response to many requests, the AIATSIS Library has received permission to digitise and make it available on our website. This book is an invaluable source for the family and social history of the Nyungar people of south western Australia. In recognition of the book's importance, the Library has indexed this book comprehensively in its Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Biographical Index (ABI). Nyungar Tradition by Lois Tilbrook is based on the South West Aboriginal Studies project (SWAS) - in which photographs have been assembled, not only from mission and government sources but also, importantly in Part ll, from the families. Though some of these are studio shots, many are amateur snapshots. The main purpose of the project was to link the photographs to the genealogical trees of several families in the area, including but not limited to Hansen, Adams, Garlett, Bennell and McGuire, enhancing their value as visual documents. The AIATSIS Library acknowledges there are varying opinions on the information in this book. An alternative higher resolution electronic version of this book (PDF, 45.5Mb) is available from the following link. Please note the very large file size. http://www1.aiatsis.gov.au/exhibitions/e_access/book/m0022954/m0022954_a.pdf Consult the following resources for more information: Search the Aboriginal & Torres Strait Islander Biographical Index (ABI) : ABI contains an extensive index of persons mentioned in Nyungar tradition. -

080052-16.022.Pdf

ver the years,land for regional parks has been identified, progressivelypurchased and managed by the Western Australian Plannin$ Commission.ln 1997,responsibility for managingand protecting eight regional parks beganto be transferredgradually to the Depatment of Consenrationand LandManagement (CALM). The parks- Yellagonga,Herdsman Lake, Rockingham Lakes,Woodman Point, CanningRiver, Beeliar, Jandakot (Botanic) Park and DarlingRange-include river foreshores, ocean beaches,wetlands, banksia woodlandsand the DarlingScarp. They contain a number of featuresand land uses,including reseryes for recreation puposes, managed by relevant local governments. Each park has its own and visitors. With local involvement, Giventhe complexissues and the unique history. the Unit aims to develop facilities to need to closely monitor parks on a cooperatively BUSHIN THE CITY createa placefor peopleto use.enjoy regular basis,working and developa feeling of ownership. with local community groupsand local Formed two years ago, CALM'S The eight regional parks span the governments is very important. The RegionalParks Unit worksclosely with map from Joondalup in Perth's parksbenefit from council rangers,local local councils and community groups northern suburbsto Port Kennedyjust citizens and CALM officers working to managethese diverse,multipurpose south of Rockinghamand inland to the togetheron managementissues. parksfor the enjoymentoflocal residents Darling Range.These urban parksare Each regionalpark may havespecial usedon a daily basisby the community, physical -

WABN #079 1996 Sep.Pdf

I Western Australian 1 Bird Notes Quarterly Newsletter of the WA Group Royal Australasian Ornithologists Union Sighting of Purple-backed Starling (Sturnus sturninus) on Christmas Island On 4 June 1996 our family were sitting on the east a Brown Shrike. We contacted Richard Hill, RAOU Project verandah of House MQ63 1 at Silver City, Christmas Island, Officer on Christmas Island, who was fortunately willing and Indian Ocean. Graham saw a bird in the bushes along the able to come to have a look. He brought two Asian field guides. fenceline. At first glance it appeared to be a honeyeater These were MacKinnon and Phillipps (1993) and King et al. approximately the size of a Tawny-crowned Honeyeater (1984). (Phylidonyris rnelanops). Graham collected the binoculars From our description, Richard indicated the starlings on (Zeiss 8 x 20 B and Nikon 8 x 32). We ventured closer for a Plate 82 of MacKinnon and Phillipps, (1993). The male better look at it. It was moving around the small white flowers Purple-backed Starling was a distinct likeness. on a garden fenceline shrub, acting like a honeyeater, but its We looked around the garden and eventually a bird flew beak, instead of being long and curved, was quite straight. from a tree adjacent to the fenceline. It landed in a tall acacia, It was a light grey bird approximately 18 cm in length. Lucaena leucocephala in the neighbour's yard. Richard and I The head and body appeared very sleek with a shortish tail in went to one side of the tree and Graham went to the other. -

Annual Report 2008-2009 Annual Report 0

Department of Environment and Conservation and Environment of Department Department of Environment and Conservation 2008-2009 Annual Report 2008-2009 Annual Report Annual 2008-2009 0 ' "p 2009195 E R N M O V E G N T E O H T F W A E I S L T A E R R N A U S T Acknowledgments This report was prepared by the Corporate Communications Branch, Department of Environment and Conservation. For more information contact: Department of Environment and Conservation Level 4 The Atrium 168 St Georges Terrace Perth WA 6000 Locked Bag 104 Bentley Delivery Centre Western Australia 6983 Telephone (08) 6364 6500 Facsimile (08) 6364 6520 Recommended reference The recommended reference for this publication is: Department of Environment and Conservation 2008–2009 Annual Report, Department of Environment and Conservation, 2009. We welcome your feedback A publication feedback form can be found at the back of this publication, or online at www.dec.wa.gov.au. ISSN 1835-1131 (Print) ISSN 1835-114X (Online) 8 September 2009 Letter to THE MINISter Back Contents Forward Hon Donna Faragher MLC Minister for Environment In accordance with section 63 of the Financial Management Act 2006, I have pleasure in submitting for presentation to Parliament the Annual Report of the Department of Environment and Conservation for the period 1 July 2008 to 30 June 2009. This report has been prepared in accordance with provisions of the Financial Management Act 2006. Keiran McNamara Director General DEPARTMENT OF ENVIRONMENT AND CONSERVATION 2008–2009 ANNUAL REPORT 3 DIRECTOR GENERAL’S FOREWORD Back Contents Forward This is the third annual report of the Department of Environment and Conservation since it was created through the merger of the former Department of Environment and Department of Conservation and Land Management. -

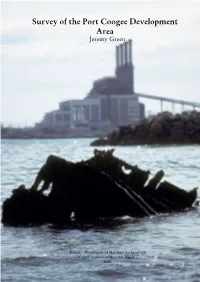

Survey of the Port Coogee Development Area Jeremy Green

Survey of the Port Coogee Development Area Jeremy Green Report—Department of Maritime Archaeology Western Australian Museum, No. 213 2006 Figure . Plan showing breakwater of proposed Port Coogee development, together with positions of wreck sites and objects of interest. Introduction current positions relative to chart datum. Additionally, The Port Coogee Development involves the historical research was carried out to try and identify construction of breakwaters and dredged channels other material that was known to have been located in an area approximately 500 m offshore extending in the general area. from latitude 32.09678°S longitude 5.75927°E south to the 32.04926°S 115.67788°E (note all The project aims latitude and longitude are given in decimal degrees and in WGS984 datum); a distance of about 000 m . To locate and precisely delineate the James, Diana (see Figure ). At the north end of the development and Omeo sites; the position of two important wreck sites are known: 2. To survey the area of the Port Coogee development James(830) and (Diana878); at the south end of that will either cover the sea bed or be affected by the development the remains of the iron steamship dredging for cultural remains; and Omeo (905) are still visible (for the background 3. To establish datum points in the James and Diana history of these three vessels see Appendix ). Since the site area and on the Omeo so that changes in the development is in an important historical anchorage level of the sea bed and movements of the wrecks area, Owen Anchorage, there is a possibility that can be monitored in the future. -

The Beeliar Group Speaks Outa

Beeliar Group Statement 1, Revision 1 Urgent need for action: the Beeliar Group speaks outa The Beeliar Group takes a strong stand against the destruction of precious West Australian wetlands and woodlands (the Beeliar Regional Park), and calls for an immediate halt to work on Roe 8, a major highway development that will traverse them. In so doing, we propose an alternative long-term agenda. Our rationale is set out below. 1. Valuable ecological communities, fauna and flora are subordinated to short-term political gain and vested interests. Roe 8 fragments one of the best remaining patches of Banksia woodland left in the Swan coastal region, which is part of an internationally recognised biodiversity hotspot. In September 2016, the Banksia Woodlands of the Swan Coastal Plain was listed as an endangered ecological community in accordance with the Commonwealth’s Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act (1999). The Commonwealth document, Banksia Woodlands of the Swan Coastal Plain: a nationally protected ecological community, drew attention to the importance of the area and the dangers of fragmentation: “[Banksia woodland] was once common and formed an almost continuous band of large bushland patches around Perth and other near coastal areas, but has been lost by almost 60% overall, with most remaining patches small in size. This fragmentation is leading to the decline of many plants, animals and ecosystem functions. Therefore, it is very important to protect, manage and restore the best surviving remnants for future generations.1 -

Minutes of the Special Meeting of the Council Held

MINUTES OF THE SPECIAL MEETING OF THE COUNCIL HELD ON TUESDAY, 21 OCTOBER 2019 AT 6.30PM IN THE COUNCIL CHAMBERS MELVILLE CIVIC CENTRE DISCLAIMER PLEASE READ THE FOLLOWING IMPORTANT DISCLAIMER BEFORE PROCEEDING: Any plans or documents in agendas and minutes may be subject to copyright. The express permission of the copyright owner must be obtained before copying any copyright material. Any statement, comment or decision made at a Council or Committee meeting regarding any application for an approval, consent or licence, including a resolution of approval, is not effective as an approval of any application and must not be relied upon as such. Any person or entity who has an application before the City must obtain, and should only rely on, written notice of the City’s decision and any conditions attaching to the decision, and cannot treat as an approval anything said or done at a Council or Committee meeting. Any advice provided by an employee of the City on the operation of written law, or the performance of a function by the City, is provided in the capacity of an employee, and to the best of that person’s knowledge and ability. It does not constitute, and should not be relied upon, as a legal advice or representation by the City. Any advice on a matter of law, or anything sought to be relied upon as representation by the City should be sought in writing and should make clear the purpose of the request. In accordance with the Council Policy CP- 088 Creation, Access and Retention of Audio Recordings of the Public Meetings this meeting is electronically recorded. -

Western Australias National and Marine Parks Guide

Western Australia’s national parks Your guide to visiting national, regional and marine parks in WA INSIDE FIND: • 135 parks to explore • Park facilities • Need-to-know information • Feature parks dbca.wa.gov.au exploreparks.dbca.wa.gov.au GOVERNMENT OF WESTERN AUSTRALIA Need to know Quicklinks exploreparks.dbca.wa.gov.au/quicklinks/ Contents Welcome 2 Need to know 3 Safety in parks 6 Emergency information 7 Tourism information, accommodation and tours 8 Park information Legend 9 Australia’s North West 10 Australia’s Coral Coast 18 Experience Perth 26 Australia’s Golden Outback 38 Australia’s South West 46 Index of parks 58 Helpful contacts 61 Access the following sites: Explore Parks WA An online guide to Western Australia’s parks, reserves and other recreation areas. exploreparks.dbca.wa.gov.au Park Stay WA Find details about campgrounds. Some sites can be booked in advance. parkstay.dbca.wa.gov.au Publisher: Department of Biodiversity, Conservation and Attractions (DBCA), ParkFinder WA Find parks near you with the 17 Dick Perry Avenue, Kensington, Western Australia 6151. activities and facilities you like. Photography: Tourism WA and DBCA unless otherwise indicated. Trails WA Find detailed information on many of Cover: The Gap at Torndirrup National Park. Western Australia’s most popular trails. The maps in this booklet should be used as a guide only and not for trailswa.com.au navigational purposes. Park safety and updates Locate up to date information including notifications and alerts for parks and trails as well as links to prescribed burns advice and bushfire and smoke alerts at emergency.wa.gov.au Park passes Buy a pass online and save time and money.