When Religion and the Law Fuse Huntington's Thesis Is Evident Both Empirically and Normatively

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Religious Diversity in America an Historical Narrative

Teaching Tool 2018 Religious Diversity in America An Historical Narrative Written by Karen Barkey and Grace Goudiss with scholarship and recommendations from scholars of the Haas Institute Religious Diversity research cluster at UC Berkeley HAASINSTITUTE.BERKELEY.EDU This teaching tool is published by the Haas Institute for a Fair and Inclusive Society at UC Berkeley This policy brief is published by About the Authors Citation the Haas Institute for a Fair and Karen Barkey is Professor of Barkey, Karen and Grace Inclusive Society. This brief rep- Sociology and Haas Distinguished Goudiss. “ Religious Diversity resents research from scholars Chair of Religious Diversity at in America: An Historical of the Haas Institute Religious Berkeley, University of California. Narrative" Haas Institute for Diversities research cluster, Karen Barkey has been engaged a Fair and Inclusive Society, which includes the following UC in the comparative and historical University of California, Berkeley, Berkeley faculty: study of empires, with special CA. September 2018. http:// focus on state transformation over haasinstitute.berkeley.edu/ Karen Munir Jiwa time. She is the author of Empire religiousdiversityteachingtool Barkey, Haas Center for of Difference, a comparative study Distinguished Islamic Studies Published: September 2018 Chair Graduate of the flexibility and longevity of Sociology Theological imperial systems; and editor of Union, Berkeley Choreography of Sacred Spaces: Cover Image: A group of people are march- Jerome ing and chanting in a demonstration. Many State, Religion and Conflict Baggett Rossitza of the people are holding signs that read Resolution (with Elazar Barkan), "Power" with "building a city of opportunity Jesuit School of Schroeder that works for all" below. -

Protestant Diffusion and Church Location in Central America, with a Case Study from Southwestern Honduras

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1997 Moved by the Spirit: Protestant Diffusion and Church Location in Central America, With a Case Study From Southwestern Honduras. Terri Shawn Mitchell Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Mitchell, Terri Shawn, "Moved by the Spirit: Protestant Diffusion and Church Location in Central America, With a Case Study From Southwestern Honduras." (1997). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 6396. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/6396 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the tact directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type o f computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. -

Carving a New Notch in the Bible Belt: Rescuing the Women of Kentucky Molly Dunn Eastern Kentucky University

Eastern Kentucky University Encompass Online Theses and Dissertations Student Scholarship January 2016 Carving a New Notch in the Bible Belt: Rescuing the Women of Kentucky Molly Dunn Eastern Kentucky University Follow this and additional works at: https://encompass.eku.edu/etd Part of the Criminology and Criminal Justice Commons Recommended Citation Dunn, Molly, "Carving a New Notch in the Bible Belt: Rescuing the Women of Kentucky" (2016). Online Theses and Dissertations. 362. https://encompass.eku.edu/etd/362 This Open Access Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship at Encompass. It has been accepted for inclusion in Online Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Encompass. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STATEMENTOF PERMISSIONTO USE In presenting this thesis in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a Master's of Science degree at Eastern Kentucky University, I agree that the Library shall make it available to borrowers under rules of the Library. Brief quotationsfrom this thesis are allowable without special permission, provided that accurate acknowledgment of the sourceis made. Permissionfor extensivequotation from or reproduction of this thesis may be grantedby my major professor,or in her absence,by the Head of Interlibrary Services when, in the opinion of either, the proposeduse of the material is for scholarly purposes. Any copying or use of the material in this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without mv written oermission. -

Religion and Geography

Park, C. (2004) Religion and geography. Chapter 17 in Hinnells, J. (ed) Routledge Companion to the Study of Religion. London: Routledge RELIGION AND GEOGRAPHY Chris Park Lancaster University INTRODUCTION At first sight religion and geography have little in common with one another. Most people interested in the study of religion have little interest in the study of geography, and vice versa. So why include this chapter? The main reason is that some of the many interesting questions about how religion develops, spreads and impacts on people's lives are rooted in geographical factors (what happens where), and they can be studied from a geographical perspective. That few geographers have seized this challenge is puzzling, but it should not detract us from exploring some of the important themes. The central focus of this chapter is on space, place and location - where things happen, and why they happen there. The choice of what material to include and what to leave out, given the space available, is not an easy one. It has been guided mainly by the decision to illustrate the types of studies geographers have engaged in, particularly those which look at spatial patterns and distributions of religion, and at how these change through time. The real value of most geographical studies of religion in is describing spatial patterns, partly because these are often interesting in their own right but also because patterns often suggest processes and causes. Definitions It is important, at the outset, to try and define the two main terms we are using - geography and religion. What do we mean by 'geography'? Many different definitions have been offered in the past, but it will suit our purpose here to simply define geography as "the study of space and place, and of movements between places". -

Wahhabism in the Balkans

k Advanced Research and Assessment Group Balka ns Series 08/06 Defence Academy of the United Kingdom Wahhabism in the Balkans Kenneth Morrison Key Points * Growing concern over the rise of Wahhabism in the Balkans have dictated that the issue has shifted from the margins to the mainstream, fast becoming recognised as one the key political-security issues in the Western Balkan region. * The growth of Wahhabi groups in the region should be treated with caution. Incidents involving Wahhabi groups in Serbia (including Kosovo), Montenegro, and Macedonia demonstrate that the Wahhabi movement is no longer isolated within the territorial confines of Bosnia and Herzegovina. * Its proliferation presents a challenge for already strained inter- ethnic relations and, more importantly, intra-Muslim relations in the region. It is imperative that the ongoing situation is not ignored or misunderstood by Western policy-makers. Contents Introduction 1 The Roots and Channels of Wahhabism 2 Wahhabism in Bosnia and Herzegovina 3 The Wahhabi Movement in Serbian Sandžak 7 Montenegro and Macedonia: The Islamic Community Prevails 9 Conclusion 10 08/06 Wahhabism in the Balkans Kenneth Morrison Introduction Followers of the doctrine of Wahhabism have established a presence and become increasingly active throughout the Western Balkan region during the last decade, most notably in Bosnia and Herzegovina and the Sandžak (Serbia and Montenegro). The war in Bosnia, which raged between 1992 and 1995, changed irreversibly the character of Bosnian Islam. Even before the outbreak of war, internal strains within the Muslim SDA (Party for Democratic Action) emerged between a more moderate, secular faction led by Adil Zufilkarpašić, and a more religious and fundamentalist faction, led by Alija Izetbegović.1 One of the key fundamental changes wrought by this internal struggle was the change in the nature and structure of Bosnian Islam. -

Vernacular Regions in Kansas 73

vernacular regions in kansas james r. shortridge Students of American culture are accustomed to seeing the nation divided into regions at many scales. At one level phrases such as New England, the South, and the Middle West are used to define areas of supposed homogeneity, and the regionalization process continues at increasingly finer scales until neighborhoods and similar sized units appear. It is an important, but rarely asked, question whether or not these regional creations of academicians and others bear a re semblance to what one may call vernacular regions, those regions perceived to exist by people actually living in the places under con sideration. Vernacular regionalization is part of a larger issue of place aware ness or consciousness usually termed "sense of place." Such awareness has been a traditional concern of humanists and, in recent years, "sense of place" discussions have appeared with increasing frequency in popular publications. The issue has considerable practical im portance. Such varied activities as regional planning, business adver tising, and political campaigning all could profit from knowledge of how people perceptually organize space. It is ironic that modern America is discovering the importance of place awareness at the time when our increasingly mobile existence makes such a "sense" difficult to achieve. Few people now doubt the advantages, even the necessity, of being in intimate enough contact with a place to establish what Wendell Berry has termed "a continuous harmony" between man and the land.1 We lack information, however, on the status of our relation ship to the land. The study of vernacular regions perhaps can provide insights into this complex issue. -

This Land Press » South by Midwest: Or, Where Is Oklahoma? » Print 5/16/11 9:16 AM

This Land Press » South by Midwest: Or, Where is Oklahoma? » Print 5/16/11 9:16 AM - This Land Press - http://thislandpress.com - South by Midwest: Or, Where is Oklahoma? Posted By Russell Cobb On April 10, 2011 @ 9:22 am In Print Edition | 14 Comments I’m not much of a Facebook person. Most of the time, I passively scroll through status updates while avoiding doing something else. Recently, however, I set off a Facebook conversation that lasted for days, with far-flung acquaintances and distant relatives chiming in on what I thought was a perfectly reasonable assertion. Before I come to that assertion, let me ask you, dear reader, who I trust has at least a passing interest in the nation’s 46th state: Where is Oklahoma? Were someone on the street to ask you this question, you might turn to a political map of the United States and point to the meat cleaver above Texas. There it is, you would say, in the mid-south-central portion of the continental United States. But where is it culturally? Is it part of The South? The U.S. Census Bureau says so. Generations of venerable southern historians, such as C. Vann Woodward, have said so. And this was the assertion I casually made on Facebook. Actually, what I said was that, as a Southerner, the word “heritage” (as in “Southern heritage”) struck me as slightly sinister, but I wasn’t quite sure why. I was quickly shot down by the sister of a very good friend, who happens to live in Birmingham. -

244 Kansas History Dixie’S Disciples: the Southern Diaspora and Religion in Wichita, Kansas by Jay M

Metropolitan Baptist Church, a Southern Baptist congregation founded in 1962 at 525 West Douglas Avenue, Wichita, Kansas. Courtesy of Jay M. Price. Kansas History: A Journal of the Central Plains 40 (Winter 2017–2018): 244–261 244 Kansas History Dixie’s Disciples: The Southern Diaspora and Religion in Wichita, Kansas by Jay M. Price n the eve of Armistice Day in November 1926, the Defenders of the Christian Faith hosted a series of lectures in Wichita, Kansas, about the dangers of modernism, evolution, and textbooks that they asserted replaced sound religion with “the philosophy of evolutionary doctrine.” Founded just a year earlier, the Defenders hoped to use a series of daytime lectures at South Lawrence Baptist Church, followed by evening sessions at the city’s Arcadia Theater, to expose a dangerous secularism that was undermining American society. Local papers Ofound that the daytime events seemed to involve internecine conflicts among clergy, as when Rev. Morton Miller, chairman of the convention, railed against modernist bishops in his Methodist Episcopal denomination.1 The evening events, however, were dominated by the event’s star speaker, Minnesota Baptist preacher W. B. Riley. Wichita had seen its share of traveling evangelists, most notably Billy Sunday, who had conducted a six-week revival event in 1911. Now the arrival of someone of Riley’s stature connected Wichita to a profound shift that was taking place in American religion. Riley had been a major figure in the emerging fundamentalist movement. He was the key orga- nizer of the World’s Christian Fundamentals Association and was instrumental in promoting the term “fundamental- ist.”2 Riley was a friend of William Jennings Bryan, the charismatic antievolution icon who had conducted the legal defense for the state of Tennessee in the Scopes trial, and also of J. -

The Application of Transformational Leadership Among Christian School Leaders in the Southeast and the Mid- Atlantic North Regions

THE APPLICATION OF TRANSFORMATIONAL LEADERSHIP AMONG CHRISTIAN SCHOOL LEADERS IN THE SOUTHEAST AND THE MID- ATLANTIC NORTH REGIONS A Dissertation Presented to The Faculty of the School of Education Liberty University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Education By Dan L. Bragg June, 2008 ii THE APPLICATION OF TRANSFORMATIONAL LEADERSHIP AMONG CHRISTIAN SCHOOL LEADERS IN THE SOUTHEAST AND THE MID- ATLANTIC NORTH REGIONS by Dan L. Bragg APPROVED: COMMITTEE CHAIR Clarence C. Holland, Ed.D. COMMITTEE MEMBERS Hila J. Spear, R.N., Ph.D. Ellen Lowrie Black, Ed.D. CHAIR, GRADUATE STUDIES Scott B. Watson. Ph.D. iii Abstract Dan L Bragg: THE APPLICATION OF TRANSFORMATIONAL LEADERSHIP AMONG CHRISTIAN SCHOOL LEADERS IN THE SOUTHEAST AND THE MID- ATLANTIC NORTH REGIONS (Under the direction of Dr. Clarence C. Holland) School of Education, June 2008. Transformational Leadership is part of a growing body of research that is having impact in leadership development in every industry and service organization. The Christian schools leader can also take advantage of the ideas that integrate so well into Biblical principles. This causal comparative study utilizing correlation and parametric statistics (ANOVA) along with descriptive cross-sectional observation investigated the differences of Transformational leadership in two distinct regions to understand how transformational leadership responded to differing cultures. This research has taken a deeper look into the elements of transformational leadership that must be enacted for a Christian school to succeed and thrive in today’s changing world and procure a successful future for Christian education. There are many studies that suggested differences in aspects of culture will result in differences in the way transformational leadership is implemented and received. -

Tomo II Plan De Estudios • Maestría En Música • Doctorado En Música

UNIVERSIDAD NACIONAL AUTÓNOMA DE MÉXICO PROGRAMA DE MAESTRÍA Y DOCTORADO EN MÚSICA Tomo II Plan de Estudios Maestría en Música Doctorado en Música Grados que se otorgan Maestro en Música (Cognición Musical, Creación Musical, Educación Musical, Etnomusicología, Interpretación Musical, Musicología o Tecnología Musical) Doctor en Música (Cognición Musical, Creación Musical, Educación Musical, Etnomusicología, Interpretación Musical, Musicología o Tecnología Musical) Campos de conocimiento del Programa Cognición Musical Creación Musical Educación Musical Etnomusicología Interpretación Musical Musicología o Tecnología Musical Entidades académicas participantes Facultad de Música Instituto de Investigaciones Antropológicas Centro de Ciencias Aplicadas y Desarrollo Tecnológico Fechas de aprobación u opiniones Adecuación y Modificación del Plan de estudios de la Maestría en Música. Fecha de aprobación del Consejo Académico del Área de las Humanidades y de las Artes: 5 de agosto de 2011. Índice ACTIVIDAD ACADÉMICA COMÚN INTRODUCCIÓN A LA INVESTIGACIÓN 2 ACTIVIDAD ACADÉMICA ENCAMINADA A LA GRADUACIÓN SEMINARIO DE INVESTIGACIÓN I 7 SEMINARIO DE INVESTIGACIÓN II 10 SEMINARIO DE INVESTIGACIÓN III 13 COGNICIÓN MUSICAL ACTIVIDADES ACADÉMICAS OBLIGATORIAS ASPECTOS PSICOLÓGICOS DE LA COGNICIÓN MUSICAL 18 BASES BIOLÓGICAS DE LA COGNCIÓN MUSICAL 21 NEUROANATOMÍA 24 ASPECTOS NEUROBIOLÓGICOS DE LA COGNICIÓN MUSICAL 27 PSICOACÚSTICA GENERAL Y APLICADA 30 ACTIVIDADES ACADÉMICAS OPTATIVAS TEMAS SELECTOS DE COGNICIÓN MUSICAL 35 DESARROLLO DEL SISTEMA -

Download a PDF of the Report

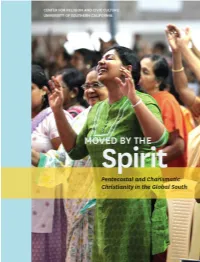

over the last two decades. And this decline has izing, non-Western countries that are bestirred by not happened painlessly. In fact, the drama has the equally potent force of free-market capitalism. played out most vividly through a conflict between This southward shift in the center of religious gravity two ministries to youth—the bellwether of global means that formerly “un-churched” peoples now Catholicism’s future. The Youth Shepherd move- play a bigger role in shaping Christian belief and ment, shaped by the folksy ethos of ’60s-era socially practice than do their co-religionists in the late- engaged Catholicism, has lost ground to Jesus colonial powers that first missionized them. Youth, a product of Catholic Charismatic Renewal. Closer to the ground, a number of more recent “Just like many of the marginal groups we want developments become apparent. Neo-Pentecostal them to try to help, our young people criticize or “next generation” churches like Igreja Renacer are social engagement for just talking and not changing now outpacing the growth of traditional Pentecostal anything,” said Boareto. “Charismatic Renewal is churches, particularly among the emerging middle changing their realities, but the question is whether classes. Unlike older denominations, many of which that experience inside the church will really change have opened Bible colleges and seminaries to train the social reality.” pastors, these newer expressions of the Pentecostal movement tend to be highly organized without being “True” Christians tied to orthodox ideas about liturgy or theology— The wave of religious renewal that has swept in fact, they tend to eschew most formal theological through Campinas and the rest of the developing and denominational labels. -

Bible Belt Gays: Insiders-Without Bernadette Barton Morehead State University

Volume 2 Living With Others / Crossroads Article 10 2018 Bible Belt Gays: Insiders-Without Bernadette Barton Morehead State University Follow this and additional works at: https://encompass.eku.edu/tcj Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons, Education Commons, Physical Sciences and Mathematics Commons, and the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Barton, Bernadette (2018) "Bible Belt Gays: Insiders-Without," The Chautauqua Journal: Vol. 2 , Article 10. Available at: https://encompass.eku.edu/tcj/vol2/iss1/10 This Essay is brought to you for free and open access by Encompass. It has been accepted for inclusion in The hC autauqua Journal by an authorized editor of Encompass. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Barton: Bible Belt Gays: Insiders-Without BERNADETTE BARTON BIBLE BELT GAYS: INSIDERS-WITHOUT During a Spring 2012 visit to a university nestled in the Appalachian Mountains, my hosts introduced me to an openly gay Episcopalian priest active in a variety of local progressive causes, including gay rights issues. While enjoying a buffet luncheon of Indian food, I learned that Father “Joe” (all the names are changed) had lived many years in Central Kentucky and we knew several people in common. After a run-through of our personal connections, Father Joe shared other tidbits of his life story, including that he had not been raised Episcopalian. He explained, “I grew up in a fundamentalist family who were Pentecostals, and for a time I tried to pray the gay away. I was an ex-gay leader with Exodus International.” Father Joe’s journey from conservative Christian to ex-gay spokesperson to out clergy echoed many of the stories I share in my book Pray the Gay Away: The Extraordinary Lives of Bible Belt Gays which draws on ethnographic observations and interviews with 59 lesbians and gay men from the region to explore what it means to be a Bible Belt gay.