The-Best-First-Backpacking-Trip-To-Take-In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Red Peak Pass Red Peak Pass

Tentative Itinerary – Red Peak Pass On your trip to Yosemite, our goal would be to give you an adventure that you will remember forever while also pointing out (and getting you up and behind) some of the major points in the park that most tourists want to see. Many people come for their first trip and just drive into Yosemite Valley and look up in awe. They then make plans to come back and see and do more in the future. By contacting us, we can design an outing where you can see the valley and also complete a backcountry trip that enables you to get away from the crowds and on top of some of the more famous peaks and beside some amazing waterfalls! You will finish this adventure feeling “success” and “accomplishment” and with a greater view and experience of Yosemite then most people ever receive! Red Peak Pass Trip Length: 7 Days/6 Nights Trip Highlights: Glacier Point, Illilouette Creek, unlimited high alpine lakes, rivers, Red Peak Pass, Merced Peak, Washburn Lake, Merced Lake, the Lost Valley, Little Yosemite Valley, and the Mist Trail. Total Milage: 50 miles Rating: Moderate to Strenuous. Day 1 : Meet your guide in the afternoon. Get acquainted with the group and with gear. Valley highlights (food in the front-country not included.) Camp in Yosemite Valley Backpackers camp. Day 2: After taking the 8am morning shuttle (approx. 1.5 hours) to Glacier Point where we will take in the views before heading downhill into the Illilouette Creek Valley. We will cross the creek and continue on a gradual uphill climb before picking a creek side location to camp at. -

Glacier Point Hiking Trails

Yosemite National Park National Park Service Glacier Point Area Hiking Map U.S. Department of the Interior 2.0 mi (3.2 k To m 3.1 ) Clouds Rest m i (5 3.8 mi .0 0 k . 5.8 km m) 1 7 . Half 1 m cables Dome ) k i km m 8836ft 0.5 .1 (permit mi i (3 2693m required) m 0 1.9 .8 km ) Glacier Point m k r 1 . e 2 v i (7 ( m .7 i 8 km i Bunnell 4. ) R m d Point 3 For Yosemite Valley trails and information, Four Mile . e 1 c r Trailhead ) e at Road km M Fl please see the Yosemite Valley Hiking Map ) 0.8 k 7214ft Happy Isles km 6.7 mi (1 a .6 O 2199m Trailhead (1 mi g 1 0 i .0 Vernal Fall 1. B m 1 i .6 k Little Yosemite Valley ) m km 6100ft 9 0.4 mi 3. Nevada Fall 1859m ( ) 120 i 0.6 km Sentinel m Road Trail m 1 k ) . m 4 k Crane Flat . Dome 4 .2 1.0 mi 4 4 2 ( . Wawona Tunnel 8122ft m i Bridalveil Fall 1 m 1.6 km ( i Tunnel 6 2476m i ( . Parking Area Ranger Station 2 2 m View . d Washburn 3 9 a . k 0.7 mi 0 Point m o Inspiration 1.1 km Telephone Campground Taft Point ) R Point 7503ft l Illilouette Fall 3 Illilouette Ridge a .7 m 2287m Store Restrooms t i (6 r .0 1.1 mi (1.8 km) o k Sentinel Dome r ) m Stanford m P k e ) & Taft Point 2 Point 0 . -

YOSEMITE NATIONAL PARK O C Y Lu H M Tioga Pass Entrance 9945Ft C Glen Aulin K T Ne Ee 3031M E R Hetc C Gaylor Lakes R H H Tioga Road Closed

123456789 il 395 ra T Dorothy Lake t s A Bond C re A Pass S KE LA c i f i c IN a TW P Tower Peak Barney STANISLAUS NATIONAL FOREST Mary Lake Lake Buckeye Pass Twin Lakes 9572ft EMIGRANT WILDERNESS 2917m k H e O e O r N V C O E Y R TOIYABE NATIONAL FOREST N Peeler B A Lake Crown B C Lake Haystack k Peak e e S Tilden r AW W Schofield C TO Rock Island OTH IL Peak Lake RI Pass DG D Styx E ER s Matterhorn Pass l l Peak N a Slide E Otter F a Mountain S Lake ri e S h Burro c D n Pass Many Island Richardson Peak a L Lake 9877ft R (summer only) IE 3010m F LE Whorl Wilma Lake k B Mountain e B e r U N Virginia Pass C T O Virginia S Y N Peak O N Y A Summit s N e k C k Lake k c A e a C i C e L C r N r Kibbie d YO N C n N CA Lake e ACK AI RRICK K J M KE ia in g IN ir A r V T e l N k l U e e pi N O r C S O M Y Lundy Lake L Piute Mountain N L te I 10541ft iu A T P L C I 3213m T Smedberg k (summer only) Lake e k re e C re Benson Benson C ek re Lake Lake Pass C Vernon Creek Mount k r e o Gibson e abe Upper an r Volunteer McC le Laurel C McCabe E Peak rn Lake u Lake N t M e cCa R R be D R A Lak D NO k Rodgers O I es e PLEASANT EA H N EL e Lake I r l Frog VALLEY R i E k G K C E LA e R a e T I r r Table Lake V North Peak T T C N Pettit Peak A INYO NATIONAL FOREST O 10788ft s Y 3288m M t ll N Fa s Roosevelt ia A e Mount Conness TILT r r Lake Saddlebag ILL VALLEY e C 12590ft (summer only) h C Lake ill c 3837m Lake Eleanor ilt n Wapama Falls T a (summer only) N S R I Virginia c A R i T Lake f N E i MIGUEL U G c HETCHY Rancheria Falls O N Highway 120 D a MEADOW -

Yosemite Guide Yosemite

Yosemite Guide Yosemite Where to Go and What to Do in Yosemite National Park July 29, 2015 - September 1, 2015 1, September - 2015 29, July Park National Yosemite in Do to What and Go to Where NPS Photo NPS 1904. Grove, Mariposa Monarch, Fallen the astride Soldiers” “Buffalo Cavalry 9th D, Troop Volume 40, Issue 6 Issue 40, Volume America Your Experience Yosemite, CA 95389 Yosemite, 577 PO Box Service Park National US DepartmentInterior of the Year-round Route: Valley Yosemite Valley Shuttle Valley Visitor Center Upper Summer-only Routes: Yosemite Shuttle System El Capitan Fall Yosemite Shuttle Village Express Lower Shuttle Yosemite The Ansel Fall Adams l Medical Church Bowl i Gallery ra Clinic Picnic Area l T al Yosemite Area Regional Transportation System F e E1 5 P2 t i 4 m e 9 Campground os Mirror r Y 3 Uppe 6 10 2 Lake Parking Village Day-use Parking seasonal The Ahwahnee Half Dome Picnic Area 11 P1 1 8836 ft North 2693 m Camp 4 Yosemite E2 Housekeeping Pines Restroom 8 Lodge Lower 7 Chapel Camp Lodge Day-use Parking Pines Walk-In (Open May 22, 2015) Campground LeConte 18 Memorial 12 21 19 Lodge 17 13a 20 14 Swinging Campground Bridge Recreation 13b Reservations Rentals Curry 15 Village Upper Sentinel Village Day-use Parking Pines Beach E7 il Trailhead a r r T te Parking e n il i w M in r u d 16 o e Nature Center El Capitan F s lo c at Happy Isles Picnic Area Glacier Point E3 no shuttle service closed in winter Vernal 72I4 ft Fall 2I99 m l E4 Mist Trai Cathedral ail Tr op h Beach Lo or M ey ses erce all only d R V iver E6 Nevada To & Fall The Valley Visitor Shuttle operates from 7 am to 10 pm and serves stops in numerical order. -

Wilderness-Use.Pdf

Trailhead Quota System Acquiring A Wilderness Permit Acquiring A Wilderness Permit Continued Welcome! Yosemite is a popular destination for backpackers, By reservation. Advance reservations are available From May through October, you can get permits at and it includes over 700 miles of trail and 54 for trips occurring from May through October. the following locations: The greater the obstacle, • Yosemite Valley Wilderness Center in Yosemite Most of Yosemite National Park is trailheads. Yosemite National Park has a trailhead Reservations are available up to 24 weeks (168 days), the more glory quota system limiting the number of overnight but no later than two days, before your start date. Village next to the Post Office in overcoming it. designated Wilderness—designated by • Tuolumne Meadows Wilderness Center, one mile visitors entering a particular trailhead on a given Jean Baptiste Molière Congress because the American people To reserve a permit, download a reservation form east of the Tuolumne Store, off Tioga Road wanted areas where nature and its day. This system is designed to reduce impacts from www.nps.gov/yose/planyourvisit/wild and to avoid overcrowding, in keeping with the • Big Oak Flat Information Station, immediately community of life remain unchanged by permits.htm, completely fill out the form, and Wilderness Act’s mandate of providing after the 120 West park entrance humans. You will experience nature on its fax to 209/372-0739. You may also call “outstanding opportunities for solitude.” The • The Wawona Visitor Center at Hill’s Studio own terms in Yosemite’s wilderness– 209/372-0740 or write to Wilderness Permits; quota system is based on where you begin your • Hetch Hetchy Entrance Station natural fires, falling rocks, high water stream PO Box 545; Yosemite, CA, 95389. -

Yosemite Valley Hiking Map U.S

Yosemite National Park National Park Service Yosemite Valley Hiking Map U.S. Department of the Interior To To ) S k Tioga n Tioga m e To o e k w r Road 10 Shuttle Route / Stop Road 7 Tioga . C Ranger Station C 4 n 3.I mi (year round) 6.9 mi ( Road r e i o 5.0 km y I e II.I km . 3.6 mi m n 6 k To a 9 m 5.9 km 18 Shuttle Route / Stop . C Self-guiding Nature Trail Tioga North 0 2 i Y n ( . o (summer only) 6 a Road 2 i s . d 6 m e 5.0 mi n m k i I Trailhead Parking ( 8.0 km m Bicycle / Foot Path I. it I.3 0 e ) k C m (paved) m re i ( e 2 ) ) k . Snow I Walk-in Campground m k k m Creek Hiking Trail .2 k ) Falls 3 Upper e ( e Campground i r Waterfall C Yosemite m ) 0 Fall Yosemite h I Kilometer . c r m 2 Point A k Store l 8 6936 ft . a ) y 0 2II4 m ( m I Mile o k i R 9 I. m ( 3. i 2 5 m . To Tamarack Flat North m i Yosemite Village 0 Lower (5 .2 Campground . I I Dome 2.5 mi Yosemite k Visitor Center m 7525 ft 0 Fall 3.9 km ) 2294 m . 3 k m e Cre i 2.0 mi Lower Yosemite Fall Trail a (3 To Tamarack Flat ( Medical Royal Mirror .2 0 y The Ahwahnee a m) k . -

Yosemite National Park Foundation Overview

NATIONAL PARK SERVICE • U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Foundation Document Overview Yosemite National Park California Contact Information For more information about Yosemite National Park, Call (209) 372-0200 (then dial 3 then 5) or write to: Public Information Office, P.O. Box 577, Yosemite, CA 95389 Park Description Through a rich history of conservation, the spectacular The geology of the Yosemite area is characterized by granitic natural and cultural features of Yosemite National Park rocks and remnants of older rock. About 10 million years have been protected over time. The conservation ethics and ago, the Sierra Nevada was uplifted and then tilted to form its policies rooted at Yosemite National Park were central to the relatively gentle western slopes and the more dramatic eastern development of the national park idea. First, Galen Clark and slopes. The uplift increased the steepness of stream and river others lobbied to protect Yosemite Valley from development, beds, resulting in formation of deep, narrow canyons. About ultimately leading to President Abraham Lincoln’s signing 1 million years ago, snow and ice accumulated, forming glaciers the Yosemite Grant in 1864. The Yosemite Grant granted the at the high elevations that moved down the river valleys. Ice Yosemite Valley and Mariposa Grove of Big Trees to the State thickness in Yosemite Valley may have reached 4,000 feet during of California stipulating that these lands “be held for public the early glacial episode. The downslope movement of the ice use, resort, and recreation… inalienable for all time.” Later, masses cut and sculpted the U-shaped valley that attracts so John Muir led a successful movement to establish a larger many visitors to its scenic vistas today. -

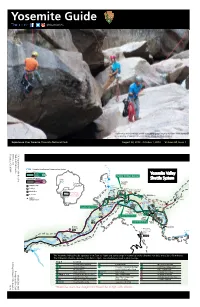

Yosemite Guide @Yosemitenps

Yosemite Guide @YosemiteNPS Yosemite's rockclimbing community go to great lengths to clean hard-to-reach areas during a Yosemite Facelift event. Photo by Kaya Lindsey Experience Your America Yosemite National Park August 28, 2019 - October 1, 2019 Volume 44, Issue 7 Yosemite, CA 95389 Yosemite, 577 PO Box Service Park National US DepartmentInterior of the Yosemite Area Regional Transportation System Year-round Route: Valley Yosemite Valley Shuttle Valley Visitor Center Summer-only Route: Upper Hetch Yosemite Shuttle System El Capitan Hetchy Shuttle Fall Yosemite Tuolumne Village Campground Meadows Lower Yosemite Parking The Ansel Fall Adams Yosemite l Medical Church Bowl i Gallery ra Clinic Picnic Area Picnic Area Valley l T Area in inset: al F e E1 t 5 Restroom Yosemite Valley i 4 m 9 The Ahwahnee Shuttle System se Yo Mirror Upper 10 3 Walk-In 6 2 Lake Campground seasonal 11 1 Wawona Yosemite North Camp 4 8 Half Dome Valley Housekeeping Pines E2 Lower 8836 ft 7 Chapel Camp Yosemite Falls Parking Lodge Pines 2693 m Yosemite 18 19 Conservation 12 17 Heritage 20 14 Swinging Center (YCHC) Recreation Campground Bridge Rentals 13 15 Reservations Yosemite Village Parking Curry Upper Sentinel Village Pines Beach il Trailhead E6 a Curry Village Parking r r T te Parking e n il i w M in r u d 16 o e Nature Center El Capitan F s lo c at Happy Isles Picnic Area Glacier Point E3 no shuttle service closed in winter Vernal 72I4 ft Fall 2I99 m l Mist Trai Cathedral ail Tr op h Beach Lo or M E4 ey ses erce all only d Ri V ver E5 Nevada Fall To & Bridalveil Fall d oa R B a r n id wo a a lv W e i The Yosemite Valley Shuttle operates from 7am to 10pm and serves stops in numerical order. -

Nevada Fall Corridor

NEVADA FALL CORRIDOR: A CULTURAL LANDSCAPE REPORT by MARTI M. GERDES A THESIS Presented to the Interdisciplinary Studies Program: Historic Preservation and the Graduate School of the University of Oregon in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science August 2004 ii "Nevada Fall Corridor: A Cultural Landscape Report," a thesis prepared by Marti M. Gerdes in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Science degree in the Interdisciplinary Studies Program: Historic Preservation. This thesis has been approved and accepted by: Robert Z. Melnick, Chair of the Examining Committee 2 Date Committee in Charge: Robert Z. Melnick, Chair Cathy Gilbert Lee Roth Fred Walters Accepted by: Dean of the Graduate School iii C 2004 Marti M. Gerdes iv An Abstract of the Thesis of Marti M. Gerdes for the degree of Master of Science in the Interdisciplinary Studies Program: Historic Preservation to be taken August 2004 Title: NEVADA FALL CORRIDOR: A CULTURAL LANDSCAPE REPORT Approved: Robert Z. Melnick This study describes existing conditions, evaluates significance and historic integrity, and recommends treatment strategies to preserve historic elements of the Nevada Fall Corridor cultural landscape in Yosemite National Park. It reports findings from field investigation that examined and inventoried landscape features such as stone retaining walls, treadway material, bridges and causeways, and water features on both current-use and abandoned trail segments. The site was examined numerous times over a three-month period, with a followup visit one year later. Libraries and other archives were consulted for written and photographic historic documentation, which were analyzed against current conditions. -

STORY of TRAIL BUILDING in YOSEMITE NATIONAL PARK by Gabriel Sovulewski of the 600 Miles of Trails That Keep Them So

DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR HUBERT WORK, SECRETARY NATIONAL PARK SERVICE YOSEMITE NATURE NOTES VOL. VII APRIL, 1928 NO. 4 "LEARN TO READ THE TRAILSIDE" YOSEMITE NATIONAL EARL, CALIF . iq9 This is the official publication of the Education ..) Depart- ment of Yosemite National Park . I t is puh ishe .i each month by the National Park Service with the co-operation of th Yosemite Natural History Association, and its purpose is to supply dependable information on the natural history and scientific features of Yosemite National Park . The artic :es published herein are not copyrighted as it is intended that they shall be freely used by the press . Communications should be addressed to C . P . Russell, Park Naturalist, Yosemite National Park, California. E. P. LEAVITT Acting Superintendent YOSEMITE NATURE NOTES THE PUBLICATION OF THE YOSEMITE EDUCATIONAL DEPARTMENT AND THE YOSEMITE NATURAL HISTORY ASSOCIATION Published monthly Volume V 1I April, 1928 Number 4 THE STORY OF TRAIL BUILDING IN YOSEMITE NATIONAL PARK By Gabriel Sovulewski Of the 600 miles of trails that keep them so . After these many exist within Yosemite boundaries, years of trail building, his enthusi- by far the greater part have been asm for such construction wanes built within the past thirty years . not at all . Just now a trails corn- In searching the old park records mittee appointed by Director made by the state park guardians, Mather is expressing its beliefs re- and the army superintendents of garding interesting foot trails along ,the national park, it became appar- Yosemite walls, and Mr . Sovulewsk; ent that dependable trail history grins like a boy as he makes his ex- was exceedingly difficult to obtain . -

Campground in Yosemite National Park

MileByMile.com Personal Road Trip Guide California Byway Highway # "Tioga Road/Big Oak Flat Road" Miles ITEM SUMMARY 0.0 End of Tioga Pass Road on Scenic Tioga Pass Road on State Highway #120, ends at the junction of State Highway #120 Big Oak Road just outside Yosemite Valley within Yosemite National Park, California. Altitude: 6158 feet 0.6 Tuolumne Grove Trail Tuolumne Grove Trail Head, Tioga Pass Road, Tuolumne Grove, is a Head sequoia grove located near Crane Flat in Yosemite National Park, California Altitude: 6188 feet 3.7 Old Big Oak Flat Road South to Tamarack Flat Campground in Yosemite National Park. Has 52 campsites, picnic tables, food lockers, fire rings, and vault toilets. Altitude: 7018 feet 6.2 Old Tioga Road Trail To Old Tioga Road, Hetch Hetchy Reservoir, lies in Hetch Hetchy Valley, which is completely flooded by the Hetch Hetchy Dam, in Yosemite National Park, California. Wapama Falls, in Hetch Hetchy Valley, Lake Vernon, Rancheria Falls, Rancheria Creek, Camp Mather Lake. Altitude: 6772 feet 6.2 Trail to Tamarrack Flat Altitude: 6775 feet Campground 13.7 Siesta Lake Altitude: 7986 feet 14.5 White Wolf Road To White Wolf Campground, located outside of Yosemite Valley, just off Tioga Pass Road in California. Altitude: 8117 feet 16.5 Access To Luken's Lake, Yosemite Creek Trail, Altitude: 8182 feet 19.7 Access A mountainous Road/Trail, Quaking Aspen Falls, is a seasonal water fall, that stream relies on rain and snow melting, dries up in summer, located just off Tioga Pass Road, in Yosemite National Park, Altitude: 7500 feet 20.3 Quaking Aspen Falls East of highway. -

Yosemite Valley Visitor Center

k e k e e r e C r Upper C n Yosemite o h y c r Fall n k A a e C e l r Yosemite Point a n C 6936ft y a Lower o 2114m i North Dome e d R t 7525ft i Yosemite n I 2294m m Fall e s ek o re Y U.S. Yosemite Valley Visitor Center C ya Court a Wilderness Center n e Museum Royal Arch T Lower Yosemite Medical Clinic Cascade Fall Trail Washington Columbia YOSEMITE Column Mirror Rock VILLAGE ROYAL Eagle Lake T ARCHES 4094ft Peak H 1248m 7779ft R The Ahwahnee Half Dome 2371m Sentinel Visitor E 8836ft Bridge Parking E North 2693m B Housekeeping Pines Camp 4 R Yosemite Camp Lower O Lodge Pines Chapel Stoneman T Bridge Middle H LeConte Brother E Memorial Road open ONLY to R Lodge pedestrians, bicycles, Ribbon S Visitor Parking and vehicles with Fall Swinging Bridge Curry Village Upper wheelchair emblem Pines Lower placards Sentinel Little Yosemite Valley El Capitan Brother Beach Trailhead for Moran 7569ft Four Mile Trail (summer only) R Point Staircase Mt Broderick i 2307m Trailhead 6706ft 6100 ft b Falls Horse Tail Parking 1859m b 2044m o Fall Trailhead for Vernal n Fall, Nevada Fall, and Glacier Point El Capitan Vernal C 7214 ft Nature Center John Muir Trail r S e e 2199 m at Happy Isles Fall Liberty Cap e n r k t 5044ft 7076ft ve i 4035ft Grizzly Emerald Ri n rced e 1230m 1538m 2157m Me l Peak Pool Silver C Northside Drive ive re Sentinel Apron Dr e North one-way Cathedral k El Capitan e Falls 0 0.5 Kilometer id To Tioga Road, Tuolumne Meadows Bridge Beach hs y ed R ut a y J and Hwy 120; and Hetch Hetchy Merc iv So -w horse trail onl o 0 0.5 Mile er