Husbandry and Management Guidelines for Demonstration Birds

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

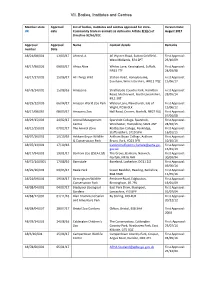

VII. Bodies, Institutes and Centres

VII. Bodies, Institutes and Centres Member state Approval List of bodies, institutes and centres approved for intra- Version Date: UK date Community trade in animals as defined in Article 2(1)(c) of August 2017 Directive 92/65/EEC Approval Approval Name Contact details Remarks number Date AB/21/08/001 13/03/17 Ahmed, A 46 Wyvern Road, Sutton Coldfield, First Approval: West Midlands, B74 2PT 23/10/09 AB/17/98/026 09/03/17 Africa Alive Whites Lane, Kessingland, Suffolk, First Approval: NR33 7TF 24/03/98 AB/17/17/005 15/06/17 All Things Wild Station Road, Honeybourne, First Approval: Evesham, Worcestershire, WR11 7QZ 15/06/17 AB/78/14/002 15/08/16 Amazonia Strathclyde Country Park, Hamilton First Approval: Road, Motherwell, North Lanarkshire, 28/05/14 ML1 3RT AB/29/12/003 06/04/17 Amazon World Zoo Park Watery Lane, Newchurch, Isle of First Approval: Wight, PO36 0LX 15/06/12 AB/17/08/065 08/03/17 Amazona Zoo Hall Road, Cromer, Norfolk, NR27 9JG First Approval: 07/04/08 AB/29/15/003 24/02/17 Animal Management Sparsholt College, Sparsholt, First Approval: Centre Winchester, Hampshire, SO21 2NF 24/02/15 AB/12/15/001 07/02/17 The Animal Zone Rodbaston College, Penkridge, First Approval: Staffordshire, ST19 5PH 16/01/15 AB/07/16/001 10/10/16 Askham Bryan Wildlife Askham Bryan College, Askham First Approval: & Conservation Park Bryan, York, YO23 3FR 10/10/16 AB/07/13/001 17/10/16 [email protected]. First Approval: gov.uk 15/01/13 AB/17/94/001 19/01/17 Banham Zoo (ZSEA Ltd) The Grove, Banham, Norwich, First Approval: Norfolk, NR16 -

Verzeichnis Der Europäischen Zoos Arten-, Natur- Und Tierschutzorganisationen

uantum Q Verzeichnis 2021 Verzeichnis der europäischen Zoos Arten-, Natur- und Tierschutzorganisationen Directory of European zoos and conservation orientated organisations ISBN: 978-3-86523-283-0 in Zusammenarbeit mit: Verband der Zoologischen Gärten e.V. Deutsche Tierpark-Gesellschaft e.V. Deutscher Wildgehege-Verband e.V. zooschweiz zoosuisse Schüling Verlag Falkenhorst 2 – 48155 Münster – Germany [email protected] www.tiergarten.com/quantum 1 DAN-INJECT Smith GmbH Special Vet. Instruments · Spezial Vet. Geräte Celler Str. 2 · 29664 Walsrode Telefon: 05161 4813192 Telefax: 05161 74574 E-Mail: [email protected] Website: www.daninject-smith.de Verkauf, Beratung und Service für Ferninjektionsgeräte und Zubehör & I N T E R Z O O Service + Logistik GmbH Tranquilizing Equipment Zootiertransporte (Straße, Luft und See), KistenbauBeratung, entsprechend Verkauf undden Service internationalen für Ferninjektionsgeräte und Zubehör Vorschriften, Unterstützung bei der Beschaffung der erforderlichenZootiertransporte Dokumente, (Straße, Vermittlung Luft und von See), Tieren Kistenbau entsprechend den internationalen Vorschriften, Unterstützung bei der Beschaffung der Celler Str.erforderlichen 2, 29664 Walsrode Dokumente, Vermittlung von Tieren Tel.: 05161 – 4813192 Fax: 05161 74574 E-Mail: [email protected] Str. 2, 29664 Walsrode www.interzoo.deTel.: 05161 – 4813192 Fax: 05161 – 74574 2 e-mail: [email protected] & [email protected] http://www.interzoo.de http://www.daninject-smith.de Vorwort Früheren Auflagen des Quantum Verzeichnis lag eine CD-Rom mit der Druckdatei im PDF-Format bei, welche sich großer Beliebtheit erfreute. Nicht zuletzt aus ökologischen Gründen verzichten wir zukünftig auf eine CD-Rom. Stattdessen kann das Quantum Verzeichnis in digitaler Form über unseren Webshop (www.buchkurier.de) kostenlos heruntergeladen werden. Die Datei darf gerne kopiert und weitergegeben werden. -

© 2006 Abcteach.Com an Owl Is a Bird. There Are Two Basic Types of Owls: Typical Owls and Barn Owls. Owls Live in Almost Every

Reading Comprehension/ Animals Name _________________________________ Date ____________________ OWLS An owl is a bird. There are two basic types of owls: typical owls and barn owls. Owls live in almost every country of the world. Owls are mostly nocturnal, meaning they are awake at night. Owls are predators- they hunt the food that they eat. Owls hunt for mice and other small mammals, insects, and even fish. Owls are well adapted for hunting. Their soft, fluffy feathers make their flight nearly silent. They have very good hearing, which helps them to hunt well in the darkness. The sharp hooked beaks and claws of the owl make it very easy to tear apart prey quickly, although owls also eat some prey whole. Owl eyes are unusual. Like most predators, both of the owl’s eyes face front. The owl cannot move its eyes. Owls are far-sighted, which means they can see very well far away… but they can’t see up close very well at all. Fortunately, their distant vision is what they use for hunting, and they can see far away even in low light. Owls have facial disks around their eyes, tufts of feathers in a circle around each eye. These facial disks are thought to help with the owl’s hearing. Owls can turn their heads 180 degrees. This makes it look like they might be able to turn their heads all the way around, but 180 degrees is all the owl needs to see what’s going on all around him. Perhaps because of the owl’s mysterious appearance, especially its round eyes and flexible neck, there are a lot of myths and superstitions about owls. -

Eastern Marsh Harrier Chu-Hi (Jpn) Circus Spilonotus Morphology and Classification Still Undiscovered Nesting Grounds in Hokkaido in Particular

Bird Research News Vol.7 No.5 2010.5.20. Eastern Marsh Harrier Chu-hi (Jpn) Circus spilonotus Morphology and classification still undiscovered nesting grounds in Hokkaido in particular. The total population of the species wintering in Japan, on the other hand, has not been counted except for the roosting number of some Classification: Accipitriformes Accipitridae areas, such as Watarase Marsh, Tochigi Pref., central Japan. Total length: ♂ 480mm ♀ 580mm Wing length: 380-430mm Wingspan: 1132-1372mm Nest: Tail length: 215-262mm Culmen length: 28-31mm They build a nest in wet reed beds or the dry tall grassland of Japa- Tarsus length: 85-91mm Weight: 498-844g nese pampas grass (Miscanthus sinensis), etc., piling up dry grass on the ground (Nishide 1979, Tada 2007, Naya et. al. 2007, Chiba Measurements after Enomoto (1941). 2008). The nest size is about 110-130cm by 80-90cm (Chiba 2008, Naya et al. 2007). Appearance: The plumage coloration of East- Egg: ern Marsh Harriers is basically They lay an egg at 3.3 day intervals on average (Nishide 1979). brownish, but varies considera- The clutch size is 4-7 eggs (Chiba 2008, Nishide 1979). The egg bly (Morioka et al. 1995). There size is 48.0mm by 38.0mm on average (n = 5) (Chiba 2008). The are types such as totally dark egg color is grayish white (Chiba 2008). brown, off-white from the head to the leading edge of a wing, Incubation and nestling periods: and pale brown with a vertical- Females mostly incubate eggs. The incubation period is about 28- striped underpart, bluish gray 34 days (Chiba 2008). -

198 Pursuit and Capture of a Ring-Billed Gull by Bald

198 Florida Field Naturalist 28(4):198-200, 2000. PURSUIT AND CAPTURE OF A RING-BILLED GULL BY BALD EAGLES ANDREW W. KRATTER1 AND MARY K. HART2 1Florida Museum of Natural History, P.O. Box 117800, University of Florida Gainesville, Florida 3261; email: kratter@flmnh.ufl.edu 2Department of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences, University of Florida Gainesville, Florida, 32611 Bald Eagles (Haliaeetus leucocephalus) are opportunistic hunters that employ a num- ber of techniques to capture a wide variety of prey (Bent 1937, Brown and Amadon 1968, Sherrod et al. 1976, McEwan and Hirth 1980). These eagles are known to occasionally pursue prey, including flying birds, in pairs or larger groups (McIlhenny 1932, Sherrod et al. 1976, Folk 1992). Here we report three Bald Eagles giving a prolonged chase of a Ring- billed Gull (Larus delawarensis), which resulted in the gull’s capture by one of the eagles. At approximately 1500 on 12 December 1998, we were kayaking east across Newnan’s Lake in eastern Alachua County, Florida, when we noticed a group of approximately 50 Ring-billed Gulls sitting on the water near the center of the lake. As we approached to approximately 100 m, the gulls lifted off when an adult Bald Eagle flew toward them at a height of about 75 m. The eagle immediately started to chase a first-winter individual. The chase was linear at first, but the gull evaded the faster flying eagle with sharp turns. Over the next three minutes, the eagle continued to chase the gull with rather slow stoops from heights of 25-100 m followed by short, fast linear pursuits. -

ATIC0943 {By Email}

Animal and Plant Health Agency T 0208 2257636 Access to Information Team F 01932 357608 Weybourne Building Ground Floor Woodham Lane www.gov.uk/apha New Haw Addlestone Surrey KT15 3NB Our Ref: ATIC0943 {By Email} 4 October 2016 Dear PROVISION OF REQUESTED INFORMATION Thank you for your request for information about zoos which we received on 26 September 2016. Your request has been handled under the Freedom of Information Act 2000. The information you requested and our response is detailed below: “Please can you provide me with a full list of the names of all Zoos in the UK. Under the classification of 'Zoos' I am including any place where a member of the public can visit or observe captive animals: zoological parks, centres or gardens; aquariums, oceanariums or aquatic attractions; wildlife centres; butterfly farms; petting farms or petting zoos. “Please also provide me the date of when each zoo has received its license under the Zoo License act 1981.” See Appendix 1 for a list that APHA hold on current licensed zoos affected by the Zoo License Act 1981 in Great Britain (England, Scotland and Wales), as at 26 September 2016 (date of request). The information relating to Northern Ireland is not held by APHA. Any potential information maybe held with the Department of Agriculture, Environment and Rural Affairs Northern Ireland (DAERA-NI). Where there are blanks on the zoo license start date that means the information you have requested is not held by APHA. Please note that the Local Authorities’ Trading Standard departments are responsible for administering and issuing zoo licensing under the Zoo Licensing Act 1981. -

Appendix 1: Maps and Plans Appendix184 Map 1: Conservation Categories for the Nominated Property

Appendix 1: Maps and Plans Appendix184 Map 1: Conservation Categories for the Nominated Property. Los Alerces National Park, Argentina 185 Map 2: Andean-North Patagonian Biosphere Reserve: Context for the Nominated Proprty. Los Alerces National Park, Argentina 186 Map 3: Vegetation of the Valdivian Ecoregion 187 Map 4: Vegetation Communities in Los Alerces National Park 188 Map 5: Strict Nature and Wildlife Reserve 189 Map 6: Usage Zoning, Los Alerces National Park 190 Map 7: Human Settlements and Infrastructure 191 Appendix 2: Species Lists Ap9n192 Appendix 2.1 List of Plant Species Recorded at PNLA 193 Appendix 2.2: List of Animal Species: Mammals 212 Appendix 2.3: List of Animal Species: Birds 214 Appendix 2.4: List of Animal Species: Reptiles 219 Appendix 2.5: List of Animal Species: Amphibians 220 Appendix 2.6: List of Animal Species: Fish 221 Appendix 2.7: List of Animal Species and Threat Status 222 Appendix 3: Law No. 19,292 Append228 Appendix 4: PNLA Management Plan Approval and Contents Appendi242 Appendix 5: Participative Process for Writing the Nomination Form Appendi252 Synthesis 252 Management Plan UpdateWorkshop 253 Annex A: Interview Guide 256 Annex B: Meetings and Interviews Held 257 Annex C: Self-Administered Survey 261 Annex D: ExternalWorkshop Participants 262 Annex E: Promotional Leaflet 264 Annex F: Interview Results Summary 267 Annex G: Survey Results Summary 272 Annex H: Esquel Declaration of Interest 274 Annex I: Trevelin Declaration of Interest 276 Annex J: Chubut Tourism Secretariat Declaration of Interest 278 -

Chromosome Painting in Three Species of Buteoninae: a Cytogenetic Signature Reinforces the Monophyly of South American Species

Chromosome Painting in Three Species of Buteoninae: A Cytogenetic Signature Reinforces the Monophyly of South American Species Edivaldo Herculano C. de Oliveira1,2,3*, Marcella Mergulha˜o Tagliarini4, Michelly S. dos Santos5, Patricia C. M. O’Brien3, Malcolm A. Ferguson-Smith3 1 Laborato´rio de Cultura de Tecidos e Citogene´tica, SAMAM, Instituto Evandro Chagas, Ananindeua, PA, Brazil, 2 Faculdade de Cieˆncias Exatas e Naturais, ICEN, Universidade Federal do Para´, Bele´m, PA, Brazil, 3 Cambridge Resource Centre for Comparative Genomics, Cambridge, United Kingdom, 4 Programa de Po´s Graduac¸a˜oem Neurocieˆncias e Biologia Celular, ICB, Universidade Federal do Para´, Bele´m, PA, Brazil, 5 PIBIC – Universidade Federal do Para´, Bele´m, PA, Brazil Abstract Buteoninae (Falconiformes, Accipitridae) consist of the widely distributed genus Buteo, and several closely related species in a group called ‘‘sub-buteonine hawks’’, such as Buteogallus, Parabuteo, Asturina, Leucopternis and Busarellus, with unsolved phylogenetic relationships. Diploid number ranges between 2n = 66 and 2n = 68. Only one species, L. albicollis had its karyotype analyzed by molecular cytogenetics. The aim of this study was to present chromosomal analysis of three species of Buteoninae: Rupornis magnirostris, Asturina nitida and Buteogallus meridionallis using fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) experiments with telomeric and rDNA probes, as well as whole chromosome probes derived from Gallus gallus and Leucopternis albicollis. The three species analyzed herein showed similar karyotypes, with 2n = 68. Telomeric probes showed some interstitial telomeric sequences, which could be resulted by fusion processes occurred in the chromosomal evolution of the group, including the one found in the tassociation GGA1p/GGA6. -

Predator and Competitor Management Plan for Monomoy National Wildlife Refuge

Appendix J /USFWS Malcolm Grant 2011 Fencing exclosure to protect shorebirds from predators Predator and Competitor Management Plan for Monomoy National Wildlife Refuge Background and Introduction Background and Introduction Throughout North America, the presence of a single mammalian predator (e.g., coyote, skunk, and raccoon) or avian predator (e.g., great horned owl, black-crowned night-heron) at a nesting site can result in adult bird mortality, decrease or prevent reproductive success of nesting birds, or cause birds to abandon a nesting site entirely (Butchko and Small 1992, Kress and Hall 2004, Hall and Kress 2008, Nisbet and Welton 1984, USDA 2011). Depredation events and competition with other species for nesting space in one year can also limit the distribution and abundance of breeding birds in following years (USDA 2011, Nisbet 1975). Predator and competitor management on Monomoy refuge is essential to promoting and protecting rare and endangered beach nesting birds at this site, and has been incorporated into annual management plans for several decades. In 2000, the Service extended the Monomoy National Wildlife Refuge Nesting Season Operating Procedure, Monitoring Protocols, and Competitor/Predator Management Plan, 1998-2000, which was expiring, with the intent to revise and update the plan as part of the CCP process. This appendix fulfills that intent. As presented in chapter 3, all proposed alternatives include an active and adaptive predator and competitor management program, but our preferred alternative is most inclusive and will provide the greatest level of protection and benefit for all species of conservation concern. The option to discontinue the management program was considered but eliminated due to the affirmative responsibility the Service has to protect federally listed threatened and endangered species and migratory birds. -

Birds of Prey (Accipitriformes and Falconiformes) of Serra De Itabaiana National Park, Northeastern Brazil

Acta Brasiliensis 4(3): 156-160, 2020 Original Article http://revistas.ufcg.edu.br/ActaBra http://dx.doi.org/10.22571/2526-4338416 Birds of prey (Accipitriformes and Falconiformes) of Serra de Itabaiana National Park, Northeastern Brazil Cleverton da Silvaa* i , Cristiano Schetini de Azevedob i , Juan Ruiz-Esparzac i , Adauto de Souza d i Ribeiro h a Programa de Pós-Graduação em Desenvolvimento e Meio Ambiente, Universidade Federal de Sergipe, Aracajú, São Cristóvão, 49100-100, Sergipe, Brasil. *[email protected] b Programa de Pós-Graduação em Ecologia de Biomas Tropicais, Universidade Federal de Ouro Preto, Ouro Preto, 35400-000, Minas Gerais, Brasil. c Universidade Federal de Sergipe, Nossa Senhora da Glória, 49680-000, Sergipe, Brasil. d Universidade Federal de Sergipe, Aracajú, São Cristóvão, 49100-100, Sergipe, Brasil. Received: June 20, 2020 / Accepted: August 27, 2020/ Published online: September 28, 2020 Abstract Birds of prey are important for maintaining ecosystems, since they can regulate the populations of vertebrates and invertebrates. However, anthropic activities, like habitat fragmentation, have been decreasing the number of birds of prey, affecting the habitat ecological relations and, decreasing biodiversity. Our objective was to evaluate species of birds of prey (Accipitriformes and Falconiformes) in a protected area of the Atlantic forest in northeastern Brazil. The area was sampled for 17 months using fixed points and walking along a pre-existing trail. Birds of prey were classified by their Punctual Abundance Index, threat status and forest dependence. Sixteen birds of prey were recorded, being the most common Rupornis magnirostris and Caracara plancus. Most species were considered rare in the area and not dependent of forest vegetation. -

DRIES ENGELEN - [email protected]

Accounting for differential migration strategies between age groups to monitor raptor population dynamics in the eastern Black Sea flyway (Vansteelant et al. In 2nd review IBIS) DRIES ENGELEN - [email protected] Photo: Adrien Brun One of the world’s largest bottlenecks for raptor migration Based on ‘Raptors of the World’ (Bildstein, 2000) Photo: Adrien Brun Targeted monitoring Priority species, secondary species Using morphological groups MonPalHen, Large Eagle, etc. Quantity vs quality Ageing (& sexing) Photo: John Wright Photo: Adrien Brun Estimated from unidentified Targeted monitoring individuals (%) Species Priority species, secondary species Avg SD Montagu’s Harrier 55,7 10,7 Pallid Harrier 50,5 11,1 Using morphological groups Western Marsh Harrier 0,2 0,1 MonPalHen, Large Eagle, etc. Black Kite 10,0 5,0 Barely mentioned (recorded?) in literature European Honey Buzzard 1,8 1,3 Booted Eagle 0,0 0,0 Quantity vs quality Short-toed Snake Eagle 0,0 0,0 Ageing (& sexing) Lesser Spotted Eagle 43,9 15,6 Photo: Adrien Brun Estimated from unidentified Targeted monitoring individuals (%) Species Priority species, secondary species Avg SD Montagu’s Harrier 55,7 10,7 Pallid Harrier 50,5 11,1 Using morphological groups Western Marsh Harrier 0,2 0,1 MonPalHen, Large Eagle, etc. Black Kite 10,0 5,0 European Honey Buzzard 1,8 1,3 Booted Eagle 0,0 0,0 Quantity vs quality Short-toed Snake Eagle 0,0 0,0 Ageing (& sexing) Lesser Spotted Eagle 43,9 Photo: John15,6 Wright Photo: Adrien Brun Age data is barely used in population trend analyses However 1) Inexperienced juveniles often behave differently than experienced conspecifics (timing, route choice, response to environmental change). -

A Contact Zone Between Mountain and Carunculated Caracaras in Ecuador.-Parker Et Al

688 THE WILSON BULLETIN l Vol. 105, No. 4, December 1993 Wilson Bull., 105(4), 1993, pp. 688-691 A contact zone between Mountain and Carunculated Caracaras in Ecuador.-Parker et al. (1985) were first to report Mountain Caracaras (Phalcoboenus megalopterus) north of the Maranon depression at Cerro Chinguela in Peru. Fjeldsa and Krabbe (1990) found them on the border of Ecuador and Peru. Ortiz et al. (1990) did not consider the species present in Ecuador, but R. Williams (pers. comm.) found Mountain Caracaras to be fairly common on the Cordillera de Cyabanilla (4”34S,’ 79”22W)’ lo-15 km east of Amaluza in 1990. However, he saw none in this area in 199 1. Williams also recorded the species at 04”2 1S,‘ 79”45W’ near Sozoranga in 1990. E. P. Toyne (pers. comm.) recorded two adult Mountain Caracaras flying together at Ingapirca (3”41S,’ 79”13W)’ on 11 April 1992 immediately east of Acacana. I recorded Mountain Caracaras several times during ornithological fieldwork at 2950 m on the east side of Cerro Acacana (Acanama) (3”41S,’ 79”14W,’ Fig. l), Province of Loja, southern Ecuador, in May and June 1992 and report on those observations here. The area is characterized by “islands” of temperate cloud forest in an “ocean” of pastures. Just below and on the top of Acacana (3420 m), plramo vegetation was prevalent. I recorded Mountain Caracaras on 15 occasions, but never more than two together at one time. Fifteen records were of adults and four of juveniles. The greatest number of sightings in any one day was four.