Community-Based Memorials to September 11, 2011: Environmental Stewardship As Memory Work

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tfft JSIM 89.95

•.••'•'•.••;' '> ^u; THE CRANFOHP CITIZEN AND CHBONICtfe, ^HUHSPAY^ 1954 a skit outlining the sity and carried on With the co- OPEN THURSDAY NIGHTS 'TIL 9 i bonw:nialung~pi roja^^ n County Home I Econom- Board of-Freeholders, the exten-. Extension Service. |. sionservice 'is. available to^aU CANCER FUND by the United States i n tcTTra-te4_homemakers. ^Mrs. hi Women's or Agriculture, ad- Mary W. Armstrong is the Union R.X jtam Rutgers Uhiver- Cftujrfyi home agfcnt. KENILWORTH Bowling Events GARWOOD terffd »J «ocoiid'clM» mall mailer GARWOOD-Mrs.-Mhs.rjr :• Vol. LXI. No. 16. CRANFORD. NEW JERSEY, THURSDAY. MAY 13r 1954 the Po>>> Office »t .Cranford. N. J. 26 Pages — TEN CENTS Scha^er of 316 Walnut avenue; — " • and'Miss Stella Tencza of East;' Rutherford, who. teamed up at • BARON'S UJA Official "ontributiom WillMelp EmkThis FhslAi&Bwldin& •^•Syracuse, - N."K., recently over the; lead in the doubles < Delinquency Rate sion" of the Womenls International Bowling Congress, will roll as Although' there are frequent Considered • partners again .this Sunday, in Teachers port* to the police of annoying doubles competition, in the Wof; m acts of mischief '<>n the part of menNfr State Bowling Tournament ELIZABETH young" people of the community, at r>^> Lanes, Mountainside..kjj Employed tTieVe- has been' no increase here For Sewer In team- • competition in .IBsL^ Proposed nf Bids for construction of Section ^ state event at Echo Lanes .on Sat-. ie~ap"poiHlment of four elemen- quency. Police Chief William A. One of the prViposed. sanitary sew- urday, Mrs., Schaeffer rolled 579 > •lPl)jtryance of Cranford Day teachers was announced to- Fischer reported this week. -

Contents PROOF

PROOF Contents List of Illustrations vii Acknowledgments viii Notes on Contributors x Technologies of Memory in the Arts: An Introduction 1 Liedeke Plate and Anneke Smelik Part I Mediating Memories Introduction: Mediating Memories 15 Liedeke Plate and Anneke Smelik 1 Tourists of History: Souvenirs, Architecture and the Kitschification of Memory 18 Marita Sturken 2 Minimalism, Memory and the Reflection of Absence 36 Wouter Weijers 3 The Virtuality of Time: Memory in Science Fiction Films 52 Anneke Smelik Part II Memory/Counter-memory Introduction: Memory/Counter-memory 71 Liedeke Plate and Anneke Smelik 4 The Astonishing Return of Blake and Mortimer: Francophone Fantasies of Britain as Imperial Power and Retrospective Rewritings 74 Ann Miller 5 Writing Back Together: The Hidden Memories of Rochester and Antoinette in Wide Sargasso Sea 86 Nagihan Haliloglu 6 Liquid Memories: Women’s Rewriting in the Present 100 Liedeke Plate v March 18, 2009 19:28 MAC/TEEM Page-v 9780230_575677_01_prexii PROOF vi Contents Part III Recalling the Past Introduction: Recalling the Past 117 Liedeke Plate and Anneke Smelik 7 The Matter and Meaning of Childhood through Objects 120 Elizabeth Wood 8 The Force of Recalling: Pain in Visual Arts 132 Marta Zarzycka 9 Photographs that Forget: Contemporary Recyclings of the Hitler-Hoffmann Rednerposen 150 Frances Guerin Part IV Unsettling History Introduction: Unsettling History 169 Liedeke Plate and Anneke Smelik 10 Facing Forward with Found Footage: Displacing Colonial Footage in Mother Dao and the Work of Fiona Tan 172 -

Organization City State 496 HHC 116Th Infantry Brigade Combat

# Organization City State 496 HHC 116th Infantry Brigade Combat Team FOB Lagman, HHC Afghanistan 553 Kadena Air-Base, Fire Emergency Services/Department APO Afghanistan 1135 United States Air Force, 438th Air Expeditionary Wing Kabul Afghanistan 147 Central Emergency Services Soldotna AK 143 Center Point Fire District Birmingham AL 180 City of Andalusia, Alabama, Police Department Andalusia AL 239 City of Mountain Brook Mountain Brook AL 545 Iron & Steel Museum of Alabama McCalla AL 713 Museum of Mobile Mobile AL 1119 Tuscaloosa Fire and Rescue Service Tuscaloosa AL 1133 United States Air Force Auxiliary, Civil Air Patrol, Springville Composite Ashville AL Squadron 130 Camden Fire Department Camden AR 200 City of El Dorado El Dorado AR 302 Conway Fire Department Conway AR 599 Little Rock Air Force Base, 19th Airlift Wing Little Rock AFB AR 916 Searcy Fire Department Searcy AR 26 Arivaca Fire District Arivaca AZ 167 Chino Valley Police Department Chino Valley AZ 194 City of Chandler Fire Department Chandler AZ 261 City of Sierra Vista Fire Department Sierra Vista AZ 273 City of Yuma Yuma AZ 361 El Mirage Fire Department El Mirage AZ 391 Family of Christina Green Tucson AZ 449 Glendale Fire Department Glendale AZ 455 Grand Canyon National Park Grand Canyon AZ 650 McMullen Valley Fire District Salome AZ 1071 Town of Gila Bend Gila Bend AZ 1072 Town of Gilbert Fire Department Gilbert AZ 1110 Transportation Security Administration/DHS, Phoenix Sky Harbor Phoenix AZ International Airport 3 452nd MSG/CEF, March Fire Department March AFB CA 37 -

The Politics of Planning the World's Most Visible Urban Redevelopment Project

The Politics of Planning the World's Most Visible Urban Redevelopment Project Lynne B. Sagalyn THREE YEARS after the terrorist attack of September 11,2001, plans for four key elements in rebuilding the World Trade Center (WC) site had been adopted: restoring the historic streetscape, creating a new public transportation gate- way, building an iconic skyscraper, and fashioning the 9/11 memorial. Despite this progress, however, what ultimately emerges from this heavily argued deci- sionmakmg process will depend on numerous design decisions, financial calls, and technical executions of conceptual plans-or indeed, the rebuilding plan may be redefined without regard to plans adopted through 2004. These imple- mentation decisions will determine whether new cultural attractions revitalize lower Manhattan and whether costly new transportation investments link it more directly with Long Island's commuters. These decisions will determine whether planned open spaces come about, and market forces will determine how many office towers rise on the site. In other words, a vision has been stated, but it will take at least a decade to weave its fabric. It has been a formidable challenge for a city known for its intense and frac- tious development politics to get this far. This chapter reviews the emotionally charged planning for the redevelopment of the WTC site between September 2001 and the end of 2004. Though we do not yet know how these plans will be reahzed, we can nonetheless examine how the initial plans emerged-or were extracted-from competing ambitions, contentious turf battles, intense architectural fights, and seemingly unresolvable design conflicts. World's Most Visible Urban Redevelopment Project 25 24 Contentious City ( rebuilding the site. -

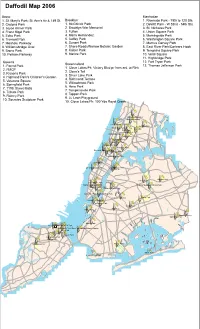

Daffodil Map 2006

Daffodil Map 2006 Bronx Manhattan 1. St. Mary's Park; St. Ann's Av & 149 St. Brooklyn 1. Riverside Park - 79th to 120 Sts. 2. Crotona Park 1. McGolrick Park 2. DeWitt Park - W 52nd - 54th Sts. 3. Joyce Kilmer Park 2. Brooklyn War Memorial 3. St. Nicholas Park 4. Franz Sigel Park 3. Fulton 4. Union Square Park 5. Echo Park 4. Maria Hernandez 5. Morningside Park 6. Tremont Park 5. Coffey Park 6. Washington Square Park 7. Mosholu Parkway 6. Sunset Park 7. Marcus Garvey Park 8. Williamsbridge Oval 7. Shore Roads/Narrow Botanic Garden 8. East River Park/Corlears Hook 9. Bronx Park 8. Kaiser Park 9. Tompkins Square Park 10. Pelham Parkway 9. Marine Park 10. Verdi Square 11. Highbridge Park Queens 12. Fort Tryon Park Staten Island 1. Forest Park 13. Thomas Jefferson Park 1. Clove Lakes Pk; Victory Blvd pr from ent. to Rink 2. FMCP 2. Clove's Tail 3. Kissena Park 3. Silver Lake Park 4. Highland Park's Children's Garden 4. Richmond Terrace 5. Veterans Square 5. Willowbrook Park 6. Springfield Park 6. Hero Park 7. 111th Street Malls 7. Tompkinsville Park 8. Tribute Park 8. Tappen Park 9. Rainey Park 9. Lt. Leah Playground 10. Socrates Sculpture Park 10. Clove Lakes Pk: 100 Yds Royal Creek Williamsbridge Oval Mosholu Parkway Fort Tryon Park Pelham Pkwy Highbridge Park Bronx Park Echo Park Tremont Park Highbridge Park Crotona Park Joyce Kilmer Park Franz Sigel Park St Nicholas Park St Mary's Park Riverside PMaorkrningside Park Marcus Garvey Park Thomas Jefferson Park Verdi Square De Witt Clinton Park Socrates Sculpture Garden Rainey Park Kissena Park 111th Street Malls Union Square Park Washington Square Park Flushing Meadows Corona Park Tompkins Square Park Monsignor Mcgolrick Park East River Park/Corlears Hook Park Maria Hernandez Park Forest Park Brooklyn War Memorial Fort Greene Park Highland Park Coffey Park Fulton Park Veterans Square Springfield Park Sunset Park Richmond TLetr.ra Nceicholaus Lia Plgd. -

Chapter 5. Historic Resources 5.1 Introduction

CHAPTER 5. HISTORIC RESOURCES 5.1 INTRODUCTION 5.1.1 CONTEXT Lower Manhattan is home to many of New York City’s most important historic resources and some of its finest architecture. It is the oldest and one of the most culturally rich sections of the city. Thus numerous buildings, street fixtures and other structures have been identified as historically significant. Officially recognized resources include National Historic Landmarks, other individual properties and historic districts listed on the State and National Registers of Historic Places, properties eligible for such listing, New York City Landmarks and Historic Districts, and properties pending such designation. National Historic Landmarks (NHL) are nationally significant historic places designated by the Secretary of the Interior because they possess exceptional value or quality in illustrating or interpreting the heritage of the United States. All NHLs are included on the National Register, which is the nation’s official list of historic properties worthy of preservation. Historic resources include both standing structures and archaeological resources. Historically, Lower Manhattan’s skyline was developed with the most technologically advanced buildings of the time. As skyscraper technology allowed taller buildings to be built, many pioneering buildings were erected in Lower Manhattan, several of which were intended to be— and were—the tallest building in the world, such as the Woolworth Building. These modern skyscrapers were often constructed alongside older low buildings. By the mid 20th-century, the Lower Manhattan skyline was a mix of historic and modern, low and hi-rise structures, demonstrating the evolution of building technology, as well as New York City’s changing and growing streetscapes. -

On May 17, 2006, Governor George E. Pataki and Mayor Michael R

FRANK J. SCIAME WORLD TRADE CENTER MEMORIAL DRAFT RECOMMENDATIONS AND ANALYSIS INTRODUCTION On May 17, 2006, Governor George E. Pataki and Mayor Michael R. Bloomberg announced that we would help lead the effort to ensure a buildable World Trade Center Memorial. The goal of our process was to ensure the World Trade Center Memorial be brought in line with the $500 million budget while remaining consistent with the Reflecting Absence vision and Daniel Libeskind’s Master Plan for the World Trade Center site. This document summarizes the findings and recommendations that arose from our process. After several phases of value engineering and analysis of the various components of the Memorial, Memorial Museum, and Visitor Orientation and Education Center (VOEC) design, we narrowed the field of options and revisions that were most promising to fulfill the vision of the Reflecting Absence design and the Master Plan, while providing significant cost savings and meeting the schedule to open the Memorial on September 11, 2009. Various potential design refinements were reviewed at a meeting with the Governor and the Mayor on June 15, 2006. Upon consultation with the Governor and the Mayor, it was determined that one option best fulfilled the three guiding principles articulated below. BACKGROUND SELECTION OF WTC SITE MASTER PLAN (Following are excerpts on the LMDC’s process – for more information please visit: http://www.renewnyc.com/plan_des_dev/wtc_site/Sept2003Overview.asp) In the summer of 2002, the Lower Manhattan Development Corporation (LMDC) initiated a worldwide search for design and planning professionals to propose a visionary land use plan for the World Trade Center area. -

The Tangible and Intangible Afterlife of Architectural Heritage Destroyed by Acts of War

REBUILDING TO REMEMBER, REBUILDING TO FORGET: THE TANGIBLE AND INTANGIBLE AFTERLIFE OF ARCHITECTURAL HERITAGE DESTROYED BY ACTS OF WAR by LAUREN J. KANE A thesis submitted to the Graduate School-New Brunswick Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Graduate Program in Art History, Cultural Heritage and Preservation Studies written under the direction of Dr. Tod Marder and approved by ________________________ ________________________ ________________________ New Brunswick, New Jersey May, 2011 ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS Rebuilding to Remember, Rebuilding to Forget: The Tangible and Intangible Afterlife of Architectural Heritage Destroyed by Acts of War by LAUREN J. KANE Thesis Director: Dr. Tod Marder Aggressors have often attacked sites of valued architectural heritage, believing such destruction will demoralize the targeted nation’s people and irreversibly shake the foundations of the marginalized culture. Of architectural structures that have been specifically targeted and fell victim to enemy attacks over the past decades however, many have been rebuilt in some capacity. This study considers the cases of Old Town Warsaw, the Stari Most in Mostar, and the former World Trade Center site in New York City to understand the ways in which local citizens engaged with the monuments tangible presence and intangible spirit prior to acts of aggression, during the monuments’ physical destruction, and throughout the process of rebuilding. From this analysis, it is concluded that while the rebuilding of valued sites of architectural heritage often reaffirms a culture’s resilience, there is no universal way to deal with the aftermath of the destruction of built heritage. -

Negotiating the Mega-Rebuilding Deal at the World Trade Center: Plans for Redevelopment

NEGOTIATING THE MEGA-REBUILDING DEAL AT THE WORLD TRADE CENTER: PLANS FOR REDEVELOPMENT DARA M. MCQUILLAN* & JOHN LIEBER ** Good morning. The current state of Lower Manhattan is the result of multiple years of planning and refinement of designs. Later I will spend a couple of minutes discussing the various buildings that we are constructing. First, to give you a little sense of perspective, Larry Silverstein,1 a quintessential New York developer, first got involved at the World Trade Center and with the Port Authority, owner of the World Trade Center,2 in 1980 when he won a bid to build 7 World Trade Center.3 In 1987, Silverstein completed the seventh tower, just north of the World Trade Center site.4 As Alex mentioned, 7 World Trade Center was not the most attractive building in New York and completely cut off Greenwich Street. Greenwich Street is the main street running through Tribeca and connects one of the most dynamic and interesting neighborhoods in New York to the financial district.5 Greenwich serves as a major link to Wall Street. I used to live in SoHo. I would walk to work at the Twin Towers every morning down Greenwich Street past the Robert DeNiro Film Center, Bazzini‘s Nuts, the parks, and the lofts of movie stars, and all of a sudden I would be in front of a 656-foot brick wall of a building. There were huge wind vortexes which often swept garbage all over the place, you could never get a cab, and it was a very * Vice President of Marketing and Communications for World Trade Center Properties, LLC, and Silverstein Properties, Inc. -

Flora and Fauna

pre-developmeNt aSSeSSmeNt of Natural reSourceS for the propoSed loNg iSlaNd – New York citY offShore wiNd project area fiNal report 10-22 taSk 3a october 2010 New York State eNergY reSearch aNd developmeNt authoritY The New York State Energy Research and Development Authority (NYSERDA) is a public benefit corporation created in 1975 by the New York State Legislature. NYSERDA derives its revenues from an annual assessment levied against sales by New York’s electric and gas utilities, from public benefit charges paid by New York rate payers, from voluntary annual contributions by the New York Power Authority and the Long Island Power Authority, and from limited corporate funds. NYSERDA works with businesses, schools, and municipalities to identify existing technologies and equipment to reduce their energy costs. Its responsibilities include: • Conducting a multifaceted energy and environmental research and development program to meet New York State’s diverse economic needs. • The New York energy $mart Sm program provides energy efficiency services, including those directed at the low-income sector, research and development, and environmental protection activities. • Making energy more affordable for residential and low-income households. • Helping industries, schools, hospitals, municipalities, not-for-profits, and the residential sector, implement energy-efficiency measures. NYSERDA research projects help the State’s businesses and municipalities with their energy and environmental problems. • Providing objective, credible, and useful -

World Trade Center Site Memorial Competition

World Trade Center Site Memorial Competition GUIDELINES Remember and honor the thousands of innocent men, women, and children murdered by terrorists in the horrific attacks of February 26, 1993 and September 11, 2001. Deadline for Registration: May 29, 2003 Deadline for Submission: June 30, 2003 Invitation to Compete Dear Competitors, On behalf of all New Yorkers, we welcome your participation in the World Trade Center Site Memorial Competition. This is the most significant public memorial project in our City’s recent history, and we are depending on the creative community for your vision and insight. Memorials serve so many essential functions: they give us a context for remembering the past, engaging the present, and reflecting on the future. We are seeking to honor the lives lost in the attacks of 9/11 on New York City – and on Washington, DC and the flight that ended in Shanksville, PA – as well as during the attack on the World Trade Center on February 26, 1993. We also need to commemorate the resilience as well as the grieving of survivors, co-workers, neighbors, and citizens profoundly affected. The values of liberty and democracy transcend geography and nationality, and they must be given physical expression as we reimagine Lower Manhattan. By taking part in this competition, you have already helped to heal our City and demonstrate once again, New York does not stand alone. Sincerely, George E. Pataki Michael R. Bloomberg Governor Mayor State of New York City of New York Letter from the LMDC Chairman Dear Competitors: On behalf of the Lower Manhattan Development Corporation, I wish to We are deeply indebted to the members of the Memorial Working extend my heartfelt appreciation and encouragement to the hundreds Group of the LMDC Board, including Deborah Wright, Tom Johnson, of people around the world who will take part in this competition. -

Official Statement Dated January 18, 2012

OFFICIAL STATEMENT DATED AUGUST 14, 2014 $346,705,000 THE PORT AUTHORITY OF NEW YORK AND NEW JERSEY CONSOLIDATED BONDS, ONE HUNDRED EIGHTY-FOURTH SERIES $483,460,000 THE PORT AUTHORITY OF NEW YORK AND NEW JERSEY CONSOLIDATED BONDS, ONE HUNDRED EIGHTY-FIFTH SERIES* Except to the extent otherwise set forth in this Official Statement, this Official Statement applies to Consolidated Bonds, One Hundred Eighty-fourth Series and Consolidated Bonds, One Hundred Eighty-fifth Series with equal force and effect, each of such series being referred to in this Official Statement without differentiation as the “Bonds.” The Bonds are direct and general obligations of The Port Authority of New York and New Jersey pledging the full faith and credit of the Port Authority for the payment of principal thereof and interest thereon. The Bonds are secured equally and ratably with all other Consolidated Bonds (which includes Consolidated Notes) heretofore or hereafter issued by a pledge of (a) the net revenues of all existing facilities of the Port Authority and any additional facilities which may hereafter be financed or refinanced in whole or in part through the medium of Consolidated Bonds, (b) the General Reserve Fund of the Port Authority equally with other obligations of the Port Authority secured by the General Reserve Fund and (c) the Consolidated Bond Reserve Fund established in connection with Consolidated Bonds. The Port Authority has no power to levy taxes or assessments. The Port Authority’s bonds, notes and other obligations are not obligations of the States of New York and New Jersey or of either of them, and are not guaranteed by said States or by either of them.