Who Were the Shudras ? ______

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Vedic Living in Modern World Contradictions of Contemporary Indian Society

International Journal of Culture and History, Vol. 2, No. 1, March 2016 Vedic Living in Modern World Contradictions of Contemporary Indian Society Kaushalya Abstract—The Vedas were the creations of the Aryans and II. ARYANS: THE WRITERS OF VEDAS the religious philosophy and values of life propounded by the Vedas were the bedrock of, what is called, the Vedic Age. Every It is an accepted fact that the Aryans wrote the Vedas [1]. era has its own social and cultural norms. Archaeological and It is also widely believed that Aryans had come to India from historical evidence suggests that rural community existed even Asia Minor. Those with imperialist predilections among in the pre-Vedic age. Scholars like Romila Thapar and D.D. them vanquished the original inhabitants in battles and Kosambi have concluded, on the basis of evidence that the pre- established their empires. On the other hand, the Rishis and Vedic public consciousness and traditions continued to live on Thinkers among them founded a religion, developed a script in parallel with the mainstream culture in the Vedic Age and this tradition did not die even after the Vedic Age. This paper and crafted a philosophy. Then, norms, rules and customs seeks to examine and study these folk traditions and the impact were developed to propagate this religion, philosophy etc. of Vedic culture, philosophy and values on them. among the masses. That brought into existence a mixed culture, which contained elements of both the Aryan as well Index Terms—Shudras, Vedic life, Varna system in India. as the local folk culture. -

The Upanishads Page

TThhee UUppaanniisshhaaddss Table of Content The Upanishads Page 1. Katha Upanishad 3 2. Isa Upanishad 20 3 Kena Upanishad 23 4. Mundaka Upanishad 28 5. Svetasvatara Upanishad 39 6. Prasna Upanishad 56 7. Mandukya Upanishad 67 8. Aitareya Upanishad 99 9. Brihadaranyaka Upanishad 105 10. Taittiriya Upanishad 203 11. Chhandogya Upanishad 218 Source: "The Upanishads - A New Translation" by Swami Nikhilananda in four volumes 2 Invocation Om. May Brahman protect us both! May Brahman bestow upon us both the fruit of Knowledge! May we both obtain the energy to acquire Knowledge! May what we both study reveal the Truth! May we cherish no ill feeling toward each other! Om. Peace! Peace! Peace! Katha Upanishad Part One Chapter I 1 Vajasravasa, desiring rewards, performed the Visvajit sacrifice, in which he gave away all his property. He had a son named Nachiketa. 2—3 When the gifts were being distributed, faith entered into the heart of Nachiketa, who was still a boy. He said to himself: Joyless, surely, are the worlds to which he goes who gives away cows no longer able to drink, to eat, to give milk, or to calve. 4 He said to his father: Father! To whom will you give me? He said this a second and a third time. Then his father replied: Unto death I will give you. 5 Among many I am the first; or among many I am the middlemost. But certainly I am never the last. What purpose of the King of Death will my father serve today by thus giving me away to him? 6 Nachiketa said: Look back and see how it was with those who came before us and observe how it is with those who are now with us. -

Indology-Studies in Germany

Indology-studies in Germany With special reference to Literature, ãgveda and Fire-Worship By Rita Kamlapurkar A thesis submitted towards the fulfilment for Degree of Ph.D. in Indology Under the guidance of Dr. Shripad Bhat And Co-Guidance of Dr. G. U. Thite Shri Bal Mukund Lohiya Centre Of Sanskrit And Indological Studies Tilak Maharashtra Vidyapeeth, Pune. December 2010. Acknowledgements : Achieving the ultimate goal while studying the Vedas might require many rebirths, as the ancient ãÈis narrate. In this scrutiny it has been tried to touch some droplets of this vast ocean of knowledge, as it’s a bold act with meagre knowledge. It is being tried to thank all those, who have extended a valuable hand in this task. I sincerely thank Dr. Shripad Bhat without whose enlightening, constant encouragement and noteworthy suggestions this work would not have existed. I thank Dr. G. U. Thite for his valuable suggestions and who took out time from his busy schedule and guided me. The constant encouragement of Dr. Sunanda Mahajan has helped me in completing this work. I thank the Librarian and staff of Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute, Pune, Maharashtra Sahitya Parishad, Pune and Tilak Maharashtra Vidyapeeth for their help. I am very much grateful to Homa-Hof-Heiligenberg, Germany, its staff and Ms. Sirgun Bracht, for keeping the questionnaire regarding the Agnihotra-practice in the farm and helping me in collecting the data. My special thanks to all my German friends for their great help. Special thanks to Dr. Ulrich Berk and the Editorial staff of ‘Homanewsletter’ for their help. -

The Mahabharata of Krishna-Dwaipayana Vyasa

The Mahabharata of Krishna-Dwaipayana Vyasa Translated into English Prose from the Original Sanskrit Text. By Kisari Mohan Ganguli [1883-1896] TRANSLATOR'S PREFACE The object of a translator should ever be to hold the mirror upto his author. That being so, his chief duty is to represent so far as practicable the manner in which his author's ideas have been expressed, retaining if possible at the sacrifice of idiom and taste all the peculiarities of his author's imagery and of language as well. In regard to translations from the Sanskrit, nothing is easier than to dish up Hindu ideas, so as to make them agreeable to English taste. But the endeavour of the present translator has been to give in the following pages as literal a rendering as possible of the great work of Vyasa. To the purely English reader there is much in the following pages that will strike as ridiculous. Those unacquainted with any language but their own are generally very exclusive in matters of taste. Having no knowledge of models other than what they meet with in their own tongue, the standard they have formed of purity and taste in composition must necessarily be a narrow one. The translator, however, would ill-discharge his duty, if for the sake of avoiding ridicule, he sacrificed fidelity to the original. He must represent his author as he is, not as he should be to please the narrow taste of those entirely unacquainted with him. Mr. Pickford, in the preface to his English translation of the Mahavira Charita, ably defends a close adherence to the original even at the sacrifice of idiom and taste against the claims of what has been called 'Free Translation,' which means dressing the author in an outlandish garb to please those to whom he is introduced. -

The Caste System

THE CASTE SYSTEM DR. DINESH VYAS ASSISTANT PROFESSOR, DEPT. OF SOCIOLOGY MAHATMA GANDHI CENTRAL UNIVERSITY, BIHAR DEFINITION MAZUMDAR & MADAN – 'CASTE IS A CLOSED CLASS’ CHARLES COOLE – "WHEN A CLASS IS SOMEWHAT STRICTLY HEREDITARY, WE MAY CALL IT A CASTE.” GHURAY – 'CASTE IS THE BRAHMIN CHILD OF THE INDO-ARJUN CULTURE, CRADLED IN THE GANGES & YAMUNA & THEN TRANSFERRED IN OTHER PARTS OF THE COUNTRY'. WHAT IS THE CASTE SYSTEM? • INDIAN SOCIETY DEVELOPED INTO A COMPLEX SYSTEM BASED ON CLASS AND CASTE • CASTE IS BASED ON THE IDEA THAT THERE ARE SEPARATE KINDS OF HUMANS • HIGHER-CASTE PEOPLE CONSIDER THEMSELVES PURER (CLOSER TO MOKSHA) THAN LOWER- CASTE PEOPLE. • THE FOUR VARNA —BRAHMAN, KSHATRIYA, VAISHYA, AND SUDRA—ARE THE CLASSICAL FOUR DIVISIONS OF HINDU SOCIETY. IN PRACTICE, HOWEVER, THERE HAVE ALWAYS BEEN MANY SUBDIVISIONS (J'ATIS) OF THESE CASTES. • THERE ARE FIVE DIFFERENT LEVELS IN THE INDIAN CASTE SYSTEM:- BRAHMAN, KSHATRIYA, VAISHYA, SHRUJRA, AND, HARIJANS. BENEFIT OF THE CASTE SYSTEM: • EACH CASTE HAS AN OCCUPATION(S) AND CONTRIBUTES TO THE GOOD OF THE WHOLE • JAJMAN—GIVES GIFT (LANDLORD) • KAMIN—GIVES SERVICE TO THE LANDHOLDER (LOWER CASTES) CASTE SYSTEM IS A KINSHIP SYSTEM; • A CASTE (VARNA) IS AN INTERMARRYING GROUP • KINSHIP; HEREDITARY MEMBERSHIP • A CASTE EATS TOGETHER • A HIGH-CASTE BRAHMIN DOES NOT EAT WITH SOMEONE OF A LOWER CASTE; DIFFERENT DIETS FOR DIFFERENT CASTES • DIVIDED BY OCCUPATION: PRIEST, WARRIOR, MERCHANT, PEASANT LEGAL STATUS, RIGHTS BASED ON CASTE MEMBERSHIP ORIGINS OF THE CASTE SYSTEM IN INDIA • NO COMMONLY APPROVED ORIGIN/HISTORY THAT EXPLAINS THE FORMATION OF INDIAN CASTE SYSTEM. • COMMON BELIEF: THE CASTE SYSTEM WAS FORMED DURING THE PERIOD OF MIGRATION OF INDO-ARYANS TO THE INDIAN SUBCONTINENT. -

Pin-Code Sl. No. Regnno Centrec Ode Centre-Name

Page 1 of 177 SL. CENTREC REGNNO CENTRE-NAME CANDIDATE'S-NAME TESTS PIN-CODE NO. ODE 1 BMB-BD-0001 BD BURDWAN AAGNIK BATABYAL SIA, SIB 713347 2 BMB-BD-0002 BD BURDWAN SOUMYABRATA MUKHERJEE SIA, SIB 713207 3 BMB-BD-0003 BD BURDWAN PULAK CHAKRABARTY SIA, SIB 713130 4 BMB-BD-0004 BD BURDWAN AVILASH BHOWMICK SIA, SIB 713335 5 BMB-BD-0005 BD BURDWAN SUPRIYO MAHATA SIA, SIB 713331 6 BMB-BD-0006 BD BURDWAN DEBARCHAN CHATTERJEE SIA, SIB 713335 7 BMB-BD-0007 BD BURDWAN MOUMITA MONDAL SIA, SIB 713331 8 BMB-BD-0008 BD BURDWAN SOUVIK DAS SIA, SIB 713365 9 BMB-BD-0009 BD BURDWAN AYON MALLIK SIA, SIB 713301 10 BMB-BD-0010 BD BURDWAN RITWIK SARKAR SIA, SIB 713103 11 BMB-BD-0011 BD BURDWAN SUSHOBHAN ADHIKARI SIA, SIB 713103 12 BMB-BD-0012 BD BURDWAN SURAJIT CHAKRABARTY SIA, SIB 713216 13 BMB-BD-0013 BD BURDWAN SAYANTAN GARAI SIA, SIB 713101 14 BMB-BD-0014 BD BURDWAN SAMIRAN PAL SIA, SIB 731215 15 BMB-BD-0015 BD BURDWAN ARITRA SAHA SIA, SIB 713101 16 BMB-BD-0016 BD BURDWAN PRAMOD BESRA SIA, SIB 713331 17 BMB-BD-0017 BD BURDWAN SUJIT KUMAR PAL SIA, SIB 713128 18 BMB-BD-0018 BD BURDWAN AKASH KUMAR SIA, SIB 713331 19 BMB-BD-0019 BD BURDWAN SANCHARI KUNDU SIA, SIB 713427 20 BMB-BD-0020 BD BURDWAN PRASUN ROYCHOWDHURY SIA, SIB 713408 21 BMB-BD-0021 BD BURDWAN SUBHAM SAHA SIA, SIB 713103 22 BMB-BD-0022 BD BURDWAN SUMANA GHOSH SIA, SIB 713148 23 BMB-BD-0023 BD BURDWAN LABANYAMOY GHOSH SIA, SIB 722207 24 BMB-BD-0024 BD BURDWAN JIBANANDA GHOSH SIA, SIB 722207 25 BMB-BD-0025 BD BURDWAN BIBEK KUMAR SIA, SIB 713331 26 BMB-BD-0026 BD BURDWAN NAWIN MOHAN SIA, SIB 713331 -

Identity and Difference in a Muslim Community in Central Gujarat, India Following the 2002 Communal Violence

Identity and difference in a Muslim community in central Gujarat, India following the 2002 communal violence Carolyn M. Heitmeyer London School of Economics and Political Science PhD 1 UMI Number: U615304 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U615304 Published by ProQuest LLC 2014. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 F Declaration I certify that the thesis I have presented for examination for the MPhil/PhD degree of the London School of Economics and Political Science is solely my own work other than where I have clearly indicated that it is the work of others (in which case the extent of any work carried out jointly by me and any other person is clearly identified in it). The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. Quotation from it is permitted, provided that full acknowledgement is made. This thesis may not be reproduced without the prior written consent of the author. I warrant that this authorization does not, to the best of my belief, infringe the rights of any third party. -

Caste System in Ancient India Spiritual Birth

learn the Vedas, so they could not participate in the initiation Name ceremony that boys of the three upper castes were entitled to when they began learning the holy texts. The ancient Indians believed that a person who had the initiation ceremony was "twice-born." The first was, of course, the person's physical birth. The second was his Caste System in Ancient India spiritual birth. As Shudras could not learn the Vedas, they would never experience a spiritual birth. Thus, they had only one birth. By Vickie Chao Though Shudras were the lowest of the four classes, they were About 3,600 years ago, a group of cattle still better off than the so-called outcastes. The outcastes, as the herders from Central Asia settled into India. name suggests, were people who did not belong to any of the four This group of people, called the Aryans, castes. They did work that nobody else wanted to do. They swept brought with them their beliefs, customs, and the streets. They collected garbage. They cleaned up toilets. And writing system (Sanskrit). They introduced a they disposed of dead animals or humans. The outcastes could not rigid caste structure that divided people into live in cities or villages. They led a lonely, humiliated life. When four classes. they ate, they could only take meals from broken dishes. When they traveled, they needed to move off the path if someone from a higher Under this setup, Brahmins or priests caste was approaching. When they entered a marketplace, they had made up the highest caste. -

Terms Used by Frithjof Schuon

Terms Used by Frithjof Schuon Editor’s Note Frithjof Schuon (1907-1998) is the foremost expositor of the Sophia Perennis . His written corpus is thus like a living body of writings. The more one reads it the more it gives of itself to the reader. Schuon either says all there is so say about a given subject, rendering the reader passive, or he provides keys to unlock doors allowing the reader an active role, with the help of virtue, prayer and grace, to participate in the life of what is being said. There is, therefore, some risk in quoting Schuon out of context. The original context of a passage contributes to its ‘ barakah’ and shade of meaning. Also, it has been said, that the editor of Schuon is like someone working with gold leaf: that which he cuts out is gold as well as that which is left behind is gold. For these reasons I have provided the full chapter as a reference. In some cases adding other chapters and books, germane to a given subject, for further study. (The only exception being Echoes of Perennial Wisdom which is a book of random extracts, here page numbers are supplied.) Deon Valodia Cape Town June 2007 “All expression is of necessity relative, but language is nonetheless capable of conveying the quality of absoluteness which has to be conveyed; expression contains all, like a seed; it opens all, like a master-key; what remains to be seen is to which capacity of understanding it is addressed.” Frithjof Schuon [SW, Orthodoxy and Intellectuality] LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS Books by Frithjof Schuon: CI – Christianity / Islam: -

Sri Arobindo Glossary to the Record of Yoga

Glossary to the Record of Yoga Introductory Note Status. Work on this glossary is in progress. Some definitions are provisional and will be revised before the glossary is published. Scope. Most words from languages other than English (primarily San- skrit), and some English words used in special senses in the Record of Yoga, are included. Transliteration. Words in italics are Sanskrit unless otherwise indi- cated. Sanskrit words are spelled according to the standard interna- tional system of transliteration. This has been adopted because the same Sanskrit word is often spelled in more than one way in the text. The spellings that occur in the text, if they differ from the transliter- ation (ignoring any diacritical marks over and under the letters), are mentioned in parentheses. The sounds represented by c, r.,ands´ or s. in the standard transliteration are commonly represented by “ch”, “ri”, and “sh” in the anglicised spellings normally used in the Record of Yoga. Order. All entries, regardless of language, are arranged in English al- phabetical order. Words and phrases are alphabetised letter by letter, disregarding diacritics, spaces and hyphens. Compounds and phrases. A compound or phrase composed of words that do not occur separately in the text is normally listed as a unit and the words are not defined individually. Compound expressions consisting of words that also occur by themselves, and thus are defined separately, are listed in the glossary only if they occur frequently or have a special significance. Definitions. The definition of each term is intended only as an aid to understanding its occurrences in the Record of Yoga. -

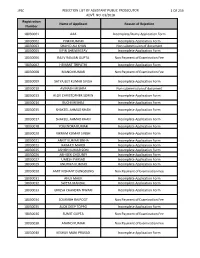

Jpsc Rejection List of Assistant Public Prosecutor 1 of 259 Advt

JPSC REJECTION LIST OF ASSISTANT PUBLIC PROSECUTOR 1 OF 259 ADVT. NO. 03/2018 Registration Name of Applicant Reason of Rejection Number 18030001 AAA Incomplete/Dumy Application Form 18030002 PINKI KUMARI Incomplete Application Form 18030003 SHAHID ALI KHAN Non submmission of document 18030005 VIPIN SHRIWASTAV Incomplete Application Form 18030006 RAJIV RANJAN GUPTA Non Payment of Examination Fee 18030007 HEMANT TRIPATHI Incomplete Application Form 18030008 MANOJ KUMAR Non Payment of Examination Fee 18030009 SATYAJEET KUMAR SINGH Incomplete Application Form 18030010 AVINASH MISHRA Non submmission of document 18030013 ALOK CHRISTOPHER SOREN Incomplete Application Form 18030014 RUCHI MISHRA Incomplete Application Form 18030015 SHAKEEL AHMAD KHAN Incomplete Application Form 18030017 SHAKEEL AHMAD KHAN Incomplete Application Form 18030018 YOGENDRA KUMAR Incomplete Application Form 18030020 VIKRAM KUMAR SINGH Incomplete Application Form 18030021 ANKIT KUMAR SINHA Incomplete Application Form 18030022 RAIMATI MARDI Incomplete Application Form 18030025 ASHISH KUMAR SONI Incomplete Application Form 18030026 ABHISEK CHOUBEY Incomplete Application Form 18030027 UMESH PARSAD Incomplete Application Form 18030029 ANUPMA KUMARI Incomplete Application Form 18030030 AMIT NISHANT DUNGDUNG Non Payment of Examination Fee 18030031 ANUJ MALIK Incomplete Application Form 18030032 SWETA MANDAL Incomplete Application Form 18030033 UMESH CHANDRA TIWARI Incomplete Application Form 18030034 SOURABH RAJPOOT Non Payment of Examination Fee 18030035 ALOK DEEP TOPPO Incomplete -

Defending Sufism, Defining Islam: Asserting Islamic Identity in India

DEFENDING SUFISM, DEFINING ISLAM: ASSERTING ISLAMIC IDENTITY IN INDIA Rachana Rao Umashankar A dissertation submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Anthropology. Chapel Hill 2012 Approved by: Dr. James L. Peacock Dr. Carl W. Ernst Dr. Margaret J. Wiener Dr. Lauren G. Leve Dr. Lorraine V. Aragon Dr. Katherine Pratt Ewing © 2012 Rachana Rao Umashankar ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT RACHANA RAO UMASHANKAR: Defending Sufism, Defining Islam: Asserting Islamic identity in India (Under the direction of Dr. James L. Peacock and Dr. Lauren G. Leve) Based on thirteen months of intensive fieldwork at two primary sites in India, this dissertation describes how adherents of shrine-based Sufism assert their identity as Indian Muslims in the contexts of public debates over religion and belonging in India, and of reformist critiques of their Islamic beliefs and practices. Faced with opposition to their mode of Islam from reformist Muslim groups, and the challenges to their sense of national identity as members of a religious minority in India, I argue that adherents of shrine-based Sufism claim the sacred space of the Sufi shrine as a venue where both the core values of Islam and of India are given form and reproduced. For these adherents, contemporary shrine-based Sufism is a dynamic and creative force that manifests essential aspects of Islam that are also fundamental Indian values, and which are critical to the health of the nation today. The dissertation reveals that contested identities and internal religious debates can only be understood and interpreted within the broader framework of national and global debates over Islam and over the place of Islam in the Indian polity that shape them.