Vulnerability of Pastoralism: a Case Study from the High Mountainsof Nepal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

TIHAR (Version Anglaise)

TIHAR (Version anglaise) http://consulat-nepal.org/spip.php?article28 TIHAR (Version anglaise) - RELIGIONS, CASTES ET ETHNIES, FÊTES TRADITIONNELLES - LES FÊTES AU NEPAL - Date de mise en ligne : samedi 17 novembre 2018 Copyright © CONSULAT DU NEPAL - Tous droits réservés Copyright © CONSULAT DU NEPAL Page 1/3 TIHAR (Version anglaise) Tihar Tihar, the festival of lights is one of the most dazzling of all Hindu festivals. In this festival we worship Goddess Laxmi, the Goddess of wealth. During the festival all the houses in the city and villages are decorated with lit oil lamps. Thus during the night the entire village or city looks like a sparkling diamond. This festival is celebrated in five days starting from the thirteenth day of the waning moon in October. We also refer to tihar as 'Panchak Yama' which literally means 'the five days of the underworld lord'. We also worship 'yamaraj' in different forms in these five days. In other words this festival is meant for life and prosperity. Goddess Laxmi is the wife of almighty Lord Vishnu. She was formed from the ocean and she has all the wealth of the seas. She sits on a full-grown lotus and her steed is the owl. On the third day of the festival at the stroke of midnight she makes a world tour on her owl looking how she is worshipped. There is a story, which tells why this revelry is celebrated so widely. Once there was a king who was living his last days of life. His astrologer had told him that a serpent would come and take his life away. -

The Politics of Culture and Identity in Contemporary Nepal

HIMALAYA, the Journal of the Association for Nepal and Himalayan Studies Volume 20 Number 1 Himalayan Research Bulletin no. 1 & Article 7 2 2000 Roundtable: The Politics of Culture and Identity in Contemporary Nepal Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/himalaya Recommended Citation . 2000. Roundtable: The Politics of Culture and Identity in Contemporary Nepal. HIMALAYA 20(1). Available at: https://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/himalaya/vol20/iss1/7 This Research Article is brought to you for free and open access by the DigitalCommons@Macalester College at DigitalCommons@Macalester College. It has been accepted for inclusion in HIMALAYA, the Journal of the Association for Nepal and Himalayan Studies by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Macalester College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Roundtable: The Politics of Culture and Identity in Contemporary Nepal Organizers: William F. Fisher and Susan Hangen Panelists: Karl-Heinz Kramer, Laren Leve, David Romberg, Mukta S. Tamang, Judith Pettigrew,and Mary Cameron William F. Fisher and Susan Hangen local populations involved in and affected by the janajati Introduction movement in Nepal. In the years since the 1990 "restoration" of democracy, We asked the roundtable participants to consider sev ethnic activism has become a prominent and, for some, a eral themes that derived from our own discussion: worrisome part of Nepal's political arena. The "janajati" 1. To what extent and to what end does it make sense movement is composed of a mosaic of social organizations to talk about a "janajati movement"? Reflecting a wide and political parties dominated by groups of peoples who variety of intentions, goals, definitions, and strategies, do have historically spoken Tibeto-Burman languages. -

Exploring Our Kaleidoscope of Cultures If

EO Files (November 2016) “THINGS WE DO, PEOPLE WE MEET – Reflections in Brief” Exploring our kaleidoscope of cultures If we have to count the favorite pastimes of Hong Kong people, traveling will no doubt rank high. While a lot of people go abroad with their mind set on good food and shopping sprees, more and more are motivated by curiosity about other cultures. The truth is we can easily experience cultures other than our own in Hong Kong without having to set foot elsewhere. In September, I was invited to the celebration of the Raksha Bandhan Festival held by a Hindu organization here in Hong Kong. I am used to celebrating Mother’s Day and Father’s Day, but it was really the first time I took part in a festival dedicated to brother-sister relationships. The event was a colorful one, with Indian performances and delicacies. Participants also made rakhi, a bracelet which sisters put on the wrists of their brothers to wish them peace and longevity. Two weeks ago, a colleague from our Ethnic Minorities Unit shared some exquisite Indian confectionery in celebration of Diwali. To have an idea of Diwali, you only have to think about the Lunar New Year – home cleaning and decorating, family gatherings, lavish meals, and fireworks, which are exactly what Indians do during this holiday. The main feature, however, is the lighting of clay lamps, which symbolizes the victory of light and good over darkness and evil. The festival is the most important holiday for Indians, enjoyed as a national festival by most regardless of their religious faith. -

Medico-Ethnobiology, Indigenous Technology and Indigenous Knowledge System of Newar Ethnic Group in Khokana Village of Lalitpur District, Nepal

MEDICO-ETHNOBIOLOGY, INDIGENOUS TECHNOLOGY AND INDIGENOUS KNOWLEDGE SYSTEM OF NEWAR ETHNIC GROUP IN KHOKANA VILLAGE OF LALITPUR DISTRICT, NEPAL Anupa Panta T.U Registration no: 5-2-1014-0004-2012 T.U Examination Roll. No. : 405/073 Batch: 2073/74 A thesis submitted for the partial fulfillment for the requirements for the award of Master’s Degree in Science (Zoology) with special paper Ecology and Environment Submitted to Central Department of Zoology Institute of Science and Technology Tribhuvan University Kirtipur, Kathmandu Nepal September, 2019 i ii iii iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I express my sincere gratitude to Prof. Dr. Nanda Bahadur Singh, Central Department of Zoology, Tribhuvan University for his incredible supervision, consistent support and invaluable gratitude throughout the dissertation preparation. I extend my hearty gratitude to Prof. Dr. Tej Bahadur Thapa, Head of Central Department of Zoology, Tribhuvan University for his motivation and support. I am grateful to National Youth Council Nepal for providing me Research grants for the field work. I would like to thank National Herbarium and Plant Laboratories (KATH) for their help in identifying unknown plant species. I would like to thank Mr. Nanda Bahadur Maharjan and Mr. Bhim Raj Tuladhar for their support during data acquisition and kind co-operation. I have special acknowledgement to all the community people of Khokana village of Lalitpur District who provided their valuable time in collection and verification of data and information during focal group discussion. I would like to extend my sincere thanks to Mr. Deepak Singh, Jashyang Rai, Ms. Kusum Kunwar, Ms. Shruti Shakya and Ms. Nilam Prajapati for their valuable time, suggestions and incredible support throughout my work. -

Nepalese Buddhists' View of Hinduism 49

46 Occasional Papers Krauskopff, Gis"le and Pamela D. Mayer, 2000. The Killgs of Nepal alld the Tha", of the Tarai. Kirlipur: Research Centre for Nepal and Asian Studies (CNAS). KrnuskoplT, Gis"le, 1999. Corvees in Dang: Ethno-HislOrical Notes, Pp. 47-62, In Harald O. Skar el. al. (eds.), Nepal: Tharu alld Tarai NEPALESE BUDDHISTS' Neighbours. Kathmandu: EMR. VIEW OF HINDUISM l Lowe, Peter, 2001. Kamaiya: Slavery and Freedom in Nepal. Kathmandu: Mandala Book Point in Association with Danish Association for Krishna B. Bhattachan International Cooperalion (MS Nepal). MUller-Boker, Ulrike, 1999. The Chitwall Tharus ill Southern Nepal: All Introduction EthnoecoJogical Approach. Franz Stiner Verlag Stuttgart 0degaard, Sigrun Eide. 1999. Base and the Role of NGO in the Process of Nepal is a multi-caste/ethnic, multi-lingual, multi-cultural and Local and Regional Change, Pp. 63-84, In Harald O. Skar (ed.l. multi-religious country. The Hindu "high castes" belong to Nepal: Tha", alld Tal'lli Neighbours. Kathmandu: EMR. Caucasoid race and they are divided into Bahun/Brahmin, Chhetri/ Rankin, Katharine, 1999. Kamaiya Practices in Western Nepal: Kshatriya, Vaisya and Sudra/Dalits and the peoples belonging to Perspectives on Debt Bondage, Pp. 27-46, In Harald O. Skar the Hill castes speak Nepali and the Madhesi castes speak various (ed.), Nepal: Tharu alld Tarai Neighbours. Kathmandu: EMR. mother tongues belonging to the same Indo-Aryan families. There Regmi, M.C., 1978. Land Tenure and Taxation in Nepal. Kathmandu: are 59 indigenous nationalities of Nepal and most of them belong to Ratna Pustak. Mongoloid race and speak Tibeto-Bumnan languages. -

The Svanti Festival: Victory Over Death and the Fenewal of The

THE SVANTI FESTIVAL: VICTORY OVER DEATH AND THE RENEWAL OF THE RITUAL CYCLE IN NEPAL Bal Gopal Shrestha Introduction Religious and ritual life in Newar society is highly guided by calendrical festivals. We can say that the Newars spend a good part of their time to organise and perform these festivals. They are highly organised when it comes to organising ritual activities. Not only in Kathmandu but also wherever the Newars have moved and settled, they managed to observe their regular feasts and festivals, rituals and traditions. Almost every month, they observe one or another festival, feast, fast or procession of gods and goddesses. As we know, almost each lunar month in Nepal contains one or another festival (nakhaQcakha!J). All year round, numerous festivals are celebrated, processions of deities are carried out and worship is performed.' Although all major and minor feasts and festivals are celebrated in every place in many ways similar the celebration of these feasts and festival in each place may vary. Moreover, there are many feasts and processions of gods and goddesses in each place, which can be called original to that place. One of the most common features of all Newar cities, towns and villages is that each of them has its specific annual festival and procession (jiifrii) of the most important deity of that particular place. The processions of different mother goddesses during Pahilqlcarhe in March or April and Indrajarra in August or September, and the processions of Rato Macchendranath in Patan and Bisket Jatra in Bhaktapur are such annual festivals. Besides observing fasts, feasts, festivals, organising processions of gods and goddesses, and making pilgrimages to religiously important places, another important feature of Newar society are the masked dances of various deities. -

NEPALESE BUDDHISTS' VIEW of Hinduisml

46 Occasional Papers Krauskopff, Gis"le and Pamela D. Mayer, 2000. The Killgs of Nepal alld the Tha", of the Tarai. Kirlipur: Research Centre for Nepal and Asian Studies (CNAS). KrnuskoplT, Gis"le, 1999. Corvees in Dang: Ethno-HislOrical Notes, Pp. 47-62, In Harald O. Skar el. al. (eds.), Nepal: Tharu alld Tarai NEPALESE BUDDHISTS' Neighbours. Kathmandu: EMR. VIEW OF HINDUISM l Lowe, Peter, 2001. Kamaiya: Slavery and Freedom in Nepal. Kathmandu: Mandala Book Point in Association with Danish Association for Krishna B. Bhattachan International Cooperalion (MS Nepal). MUller-Boker, Ulrike, 1999. The Chitwall Tharus ill Southern Nepal: All Introduction EthnoecoJogical Approach. Franz Stiner Verlag Stuttgart 0degaard, Sigrun Eide. 1999. Base and the Role of NGO in the Process of Nepal is a multi-caste/ethnic, multi-lingual, multi-cultural and Local and Regional Change, Pp. 63-84, In Harald O. Skar (ed.l. multi-religious country. The Hindu "high castes" belong to Nepal: Tha", alld Tal'lli Neighbours. Kathmandu: EMR. Caucasoid race and they are divided into Bahun/Brahmin, Chhetri/ Rankin, Katharine, 1999. Kamaiya Practices in Western Nepal: Kshatriya, Vaisya and Sudra/Dalits and the peoples belonging to Perspectives on Debt Bondage, Pp. 27-46, In Harald O. Skar the Hill castes speak Nepali and the Madhesi castes speak various (ed.), Nepal: Tharu alld Tarai Neighbours. Kathmandu: EMR. mother tongues belonging to the same Indo-Aryan families. There Regmi, M.C., 1978. Land Tenure and Taxation in Nepal. Kathmandu: are 59 indigenous nationalities of Nepal and most of them belong to Ratna Pustak. Mongoloid race and speak Tibeto-Bumnan languages. -

The Ultimate Diwali Quiz by R Ām Lingam

The Ultimate Diwali quiz By R ām Lingam Shubh Deep āvali to you and your family. Deep āvali or Diwali ~ the Hindu festival of lights brings to our mind images of diyas, sweets, puja, colourful lights, fire crackers, feasting, new purchases, socializing and lots of fun. Here is a little quiz to remind ourselves about Diwali and the origins that makes Diwali the most popular festival of India. Test your Diwali Quotient with just 15 questions. Be ready for some curly questions too and for every right answer treat yourself or your family/friend with something special. Answers are provided at the bottom of the quiz. 1. Diwali is the shortened version of Deep āvali. What does the word Deep āvali actually mean? A. Row of lighted lamps B. Festival of lights C. Circle of lights D. Light of life 2. There is no public holiday for Diwali in which of the following countries? A. Singapore B. Th āiland C. Trinidad & Tobago D. Fiji 3. Diwali commemorates the spiritual enlightenment of which two famous saints? A. Lord Vardhaman Mah āveer and Swami Day ānanda Saraswati B. Rāmakrishna Paramahansa and Chaitanya Mah āprabhu C. Swami Vivek ānanda and Ādi Shankara D. Sant Tuk ārām and Sri Aurobindo 4. Which two historical icons of India does the festival celebrate the return of? A. Krishna and Rukhmani B. King Krishnadeva R āya C. Lord R ām and Sit ā D. Rāja R āja Chola 5. What other religious groups celebrate Diwali in India, apart from Hindus? A. Pārsis and Bah āis B. Jains and Sikhs C. -

Festivals of Nepal

www.asiaexperiences.com Festivals of Nepal Overview 1. Dashain Based on the religion, the biggest festival of Dashain, a celebration of Goddess Durga’s victory over evil Mahisashur, has symbolic meaning deeply rooted in Nepalese society. Dashain is the longest (15-day- long) and the most auspicious festival in Nepal. Dashain festival falls in September or October, starting from the Shukla Paksha (bright lunar fortnight) of the month of Ashwin and ending on the full moon day (Purnima). Among the 15 days (Ghatasthapan to Purnima) for which it is celebrated, the most important days are the first (ghatasthapana), seventh (Saptami), eighth (Maha-Astami), ninth (Nawami) and the tenth (Vijaya Dasami/Tika), but tenth day is very important all over the country Shakti is worshiped in all her manifestations. Dashain festival is also known for its importance on the family gatherings, as well as on a renewal of community relations and links. People return from all parts of the world and country to celebrate together. During the festival all government offices, educational institutions and other private offices remain closed in holidays duration. 2. Tihar “Festival of Light” Tihar, Hindu festival is also known as the “Festival of Light” or Deepawali. All the houses and even the street corners are illuminated by colorful lights and bulbs. Tihar, a celebration of lights and color dedicated to Goddess Laxmi, too reveals social joy all over the country. This festival celebrated for 5 days at the end of October or in the beginning of November. Lights and colored decoration are used to decorate homes over a three to five day period. -

(Mis)Representation of Nepali Culture in the Guru of Love

The Outlook: Journal of English Studies Vol. 11, July 2020, pp. 1–13 ISSN: 2565-4748 (Print); ISSN: 2773-8124 (Online) http://www.ejournals.pncampus.edu.np/ejournals/outlook/ (Mis)representation of Nepali Culture in The Guru of Love Bhanu Bhakta Sharma Kandel Department of English, Prithvi Narayan Campus, TU, Pokhara Corresponding Author: Bhanu Bhakta Sharma Kandel, Email: [email protected] DOI: https://doi.org/10.3126/ojes.v11i0.36312 Abstract Samrat Upadhyay’s The Guru of Love has (mis)represented Nepali culture, society and thoughts from Western perspective. The writer has applied Western standards of life to represent Orient culture and society where he seems to have misguided somewhere. He has mentioned in the novel that Easterners have suffered from inferior thoughts and practices, the society has slavish mind-set regarding gender issues and sexual psychology, the society is poverty-stricken and it is full of the people with corrupt mind. The novel explains that females have been victimized from males’ domination practicing sexual violence, harassment and gender discrimination and dominance. Upadhayay has discussed about his birth place, cultures, society, language, religion, relatives, illicit sexual relation and political chaos which has helped to create a ‘discourse’ about Nepali society. The article argues how the novelist has (mis) represented the Nepai culture by discussing socio-cultural practices and it analyzes how it has tried to serve the palate of the Western readership. Keywords: Corruption, gender, (mis)representation, politics, poverty Introduction The discourse of representation of the Orient as “Other‟ is a system of representation framed by a whole set of forces that bring the non-west in to Western learning and Western consciousness according to their understanding and interpretation of the East. -

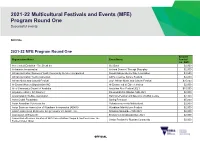

2021-22 Multicultural Festivals and Events (MFE) Program Round One Successful Events

2021-22 Multicultural Festivals and Events (MFE) Program Round One Successful events OFFICIAL 2021-22 MFE Program Round One Amount Organisation Name Event Name Funded (ex. GST) Accelerated Evolution - The Break Inc Get Back $2,000 Actomania Incorporated Act and Connect Through Stageplay $2,000 African Australian Women & Youth Community Service Incorporated Somali Independence Day Celebration $4,650 African Australian Youth Connection AAYC Creative Kulture Festival $2,000 African Music and Cultural Festival 2021 African Music and Cultural Festival $35,000 Al-Emaan Women Organisation INC Al-Emaan end of Eid celebration $2,000 Alevi Community Council of Australia Anatolian Alevi Festival 2021 $10,000 Anjuman-e-Saifee (Melbourne) Dawoodi Bohra Miladun Nabi 2021 $2,000 Ararat Islamic Welfare Association Harmony Festival and Opening of AIWA Centre $3,100 Asha Global Foundation Spring Fest 2021 $5,000 Asian Australian Volunteers Inc Volunteering meets Multicultural $2,000 Asian Business Association of Wyndham Incorporated (ABAW) Wyndham Mid-Autumn Festival $2,000 Assam Association Melbourne Inc (previously Vic Assam, Inc) Srimanta Sankardev Tithi 2021 $2,000 Association of Erayra Inc Eratyra Celebrating Oxi Day 2021 $2,000 Association of Former Inmates of Nazi Concentration Camps & Ghettoes From The Senior Festival for Russian Community $2,000 Former Soviet Union OFFICIAL 2021-22 Multicultural Festivals and Events (MFE) Program Round One – successful events 2 Amount Organisation Name Event Name Funded (ex. GST) Association of Ukrainians in Victoria -

Culture and Politics of Caste in the Himalayan Kingdom

62 Occasional Papers Gurung, Harkal987 Himali Chherrama Baudha Dharma ("Buddhism ill Himalayan Region"). A paper presented in the first national Buddhist Conference in Kathmandu. 2001 lanaganana-2ool E. Anusar laliya Talhyanka Prambhik Lekhajokha ("Erhillc Dara ill accordallce to the Cellcus of2001 CULTURE AND POLITICS OF CASTE A.D.: Preliminary Assessment"). Kathmandu: Dharmodaya Sabha. IN THE HIMALAYAN KINGDOM Guvaju, Tilak Man 1990 Ke Buddhadharma Hilldudharmako Sakha Ho Ra? ("Is Buddhism a Branch of Hinduism?"). Pokhara, Nepal: Tulshi Ram Pandey Sri prasad Tamu. (Text in Nepali). Mukunda, Acharya er al.2000 Radio Sryle Book. Kathmandu: Radio This paper defines the concept of caste as it can be derived from the Nepal. literature and attempts to highlight the modality of its manifesta SPOTLIGHT 1999 SPOTLIGHT. Vol. 19, Number 19, November 26 tions in the context of Nepal. It argues that caste as an ideology or a December 2, 1999. system of values should not be taken as a face value while it is Wadia, A.S. 1992 The Message ofBuddha. Delhi: Book Failh India. (First judged in terms of its application in field reality. Evidences from its published in 1938). practice in Nepal do suggest that it is highly molded by the cultural Weber, Max 1967 The Religioll ofIlldia. The Sociology of Hillduism alld context of society and political interest of the rulers. Many of its Buddhism. Translated and Edited by Hans H. Gerth and Don ideological elements apply only partially in field situations. Martindale. New York: The Free Press, 1967 Defining the Concept of Caste Indeed, the division of the population into a number of caste groups is one of the fundamental features of social structure in Hindu society.