Tracing the Production of Alleged Female Killers Through Discourse, Image, and Speculation by Emily Hiltz

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Face of an Angel Synopsis

THE FACE OF AN ANGEL SYNOPSIS The brutal murder of a Bri1sh student in Tuscany leads to the trial and convic1on of her American flatmate and Italian boyfriend in controversial circumstances. The media feeding frenzy around the case aracts once successful, but now struggling filmmaker Thomas, to be commissioned to write a film - 'The Face of an Angel', based on a book by Simone Ford an American journalist who covered the case. From Rome they head to Siena to research the film. Thomas has recently separated from his wife in a bi=er divorce and leI his 9-year-old daughter in Los Angeles. This unravelling of his own life, and the dark mediaeval atmosphere surrounding the case, begins to drag him down into his own personal hell. Like Dante journeying through the Inferno in the Divine Comedy, with Simone as his guide to the tragedy of the murder, Thomas starts a relaonship with a student Melanie. This is a beau1ful, unrequited love, where she acts as a guide to his own heart. He comes to realise the most important thing in his life is not solving an unsolvable crime, or wri1ng the film, but returning to the daughter he has leI behind. | THE FACE OF AN ANGEL | 1 SHEET | 15.10.2013 | 1!5 THE FACE OF AN ANGEL CAST DANIEL BRÜHL KATE BECKINSALE In 2003 Daniel Brühl took the leading role in the box office smash Good English actress Kate Beckinsale is revealing herself to be one of films’ Bye Lenin!, which became one of Germany’s biggest box office hits of all most versale and charismac actresses. -

Presents a Film by Michael Winterbottom 104 Mins, UK, 2019

Presents GREED A film by Michael Winterbottom 104 mins, UK, 2019 Language: English Distribution Publicity Mongrel Media Inc Bonne Smith 217 – 136 Geary Ave Star PR Toronto, Ontario, Canada, M6H 4H1 Tel: 416-488-4436 Tel: 416-516-9775 Fax: 416-516-0651 Twitter: @starpr2 E-mail: [email protected] E-mail: [email protected] www.mongrelmedia.com Synopsis GREED tells the story of self-made British billionaire Sir Richard McCreadie (Steve Coogan), whose retail empire is in crisis. For 30 years he has ruled the world of retail fashion – bringing the high street to the catwalk and the catwalk to the high street – but after a damaging public inquiry, his image is tarnished. To save his reputation, he decides to bounce back with a highly publicized and extravagant party celebrating his 60th birthday on the Greek island of Mykonos. A satire on the grotesque inequality of wealth in the fashion industry, the film sees McCreadie’s rise and fall through the eyes of his biographer, Nick (David Mitchell). Cast SIR RICHARD MCCREADIE STEVE COOGAN SAMANTHA ISLA FISHER MARGARET SHIRLEY HENDERSON NICK DAVID MITCHELL FINN ASA BUTTERFIELD AMANDA DINITA GOHIL LILY SOPHIE COOKSON YOUNG RICHARD MCCREADIE JAMIE BLACKLEY NAOMI SHANINA SHAIK JULES JONNY SWEET MELANIE SARAH SOLEMANI SAM TIM KEY FRANK THE LION TAMER ASIM CHAUDHRY FABIAN OLLIE LOCKE CATHY PEARL MACKIE KAREEM KAREEM ALKABBANI Crew DIRECTOR MICHAEL WINTERBOTTOM SCREENWRITER MICHAEL WINTERBOTTOM ADDITIONAL MATERIAL SEAN GRAY EXECUTIVE PRODUCER DANIEL BATTSEK EXECUTIVE PRODUCER OLLIE MADDEN PRODUCER -

Id Title Year Format Cert 20802 Tenet 2020 DVD 12 20796 Bit 2019 DVD

Id Title Year Format Cert 20802 Tenet 2020 DVD 12 20796 Bit 2019 DVD 15 20795 Those Who Wish Me Dead 2021 DVD 15 20794 The Father 2020 DVD 12 20793 A Quiet Place Part 2 2020 DVD 15 20792 Cruella 2021 DVD 12 20791 Luca 2021 DVD U 20790 Five Feet Apart 2019 DVD 12 20789 Sound of Metal 2019 BR 15 20788 Promising Young Woman 2020 DVD 15 20787 The Mountain Between Us 2017 DVD 12 20786 The Bleeder 2016 DVD 15 20785 The United States Vs Billie Holiday 2021 DVD 15 20784 Nomadland 2020 DVD 12 20783 Minari 2020 DVD 12 20782 Judas and the Black Messiah 2021 DVD 15 20781 Ammonite 2020 DVD 15 20780 Godzilla Vs Kong 2021 DVD 12 20779 Imperium 2016 DVD 15 20778 To Olivia 2021 DVD 12 20777 Zack Snyder's Justice League 2021 DVD 15 20776 Raya and the Last Dragon 2021 DVD PG 20775 Barb and Star Go to Vista Del Mar 2021 DVD 15 20774 Chaos Walking 2021 DVD 12 20773 Treacle Jr 2010 DVD 15 20772 The Swordsman 2020 DVD 15 20771 The New Mutants 2020 DVD 15 20770 Come Away 2020 DVD PG 20769 Willy's Wonderland 2021 DVD 15 20768 Stray 2020 DVD 18 20767 County Lines 2019 BR 15 20767 County Lines 2019 DVD 15 20766 Wonder Woman 1984 2020 DVD 12 20765 Blackwood 2014 DVD 15 20764 Synchronic 2019 DVD 15 20763 Soul 2020 DVD PG 20762 Pixie 2020 DVD 15 20761 Zeroville 2019 DVD 15 20760 Bill and Ted Face the Music 2020 DVD PG 20759 Possessor 2020 DVD 18 20758 The Wolf of Snow Hollow 2020 DVD 15 20757 Relic 2020 DVD 15 20756 Collective 2019 DVD 15 20755 Saint Maud 2019 DVD 15 20754 Hitman Redemption 2018 DVD 15 20753 The Aftermath 2019 DVD 15 20752 Rolling Thunder Revue 2019 -

Amid the Ice, and the Sawdust in Which It Was Stored, Lost a Valuable Watch

All Rights Reserved By HDM For This Digital Publication Copyright 2001 Holiness Data Ministry Duplication of this CD by any means is forbidden, and copies of individual files must be made in accordance with the restrictions stated in the B4UCopy.txt file on this CD. 2700-PLUS SERMON ILLUSTRATIONS (Q-R-TOPICS) Compiled and Arranged Topically by Duane V. Maxey * * * * * * * CONTENTS QUIETNESS 1982 -- Stopping To Listen READINESS 1983 -- Clean When He Comes 1984 -- Get Ready 1985 -- Make Your Reservation READINESS -- FOR SPIRITUAL SERVICE 1986 -- Dwight Moody Said It READINESS -- PRECEDES BLESSINGS 1987 -- When The Wind Blows REAPING 1988 -- A Sad Contrast 1989 -- John's Scheme Backfired RECONCILIATION 1990 -- A Wise Answer That Turned Away Wrath RECONCILIATION -- THROUGH CHRIST 1991 -- Reconciled By Death RECONCILIATION -- WITH MEN 1992 -- A Reconciliation Not Regretted 1993 -- Washington's Reconciliation With Payne REDEMPTION -- THROUGH CHRIST 1994 -- Charge It! REDEMPTION -- THROUGH CHRIST 1995 -- Love Found A Way REGENERATION 1996 -- A New Skipper Aboard 1997 -- Dead People Don't Give 1998 -- Fallen Man Needs A New Mainspring 1999 -- Not New Bands, But New Birth REJECTION -- OF CHRIST 2000 -- Afraid Of God 2001 -- Irresponsive To God 2002 -- The Weight Of Repeatedly Rejecting Christ REJECTION -- OF THE WORD OF GOD 2003 -- A Closer Look REJOICING 2004 -- Rejoicing When One Is Healed Of Sin RELIGIOUS LEADERS -- COURAGEOUS REFORMERS 2005 -- Great Growth From A Small Seed RELIGIOUS LEADERS -- HUMBLE 2006 -- Not A Bad Model RELIGIOUS LEADERS -

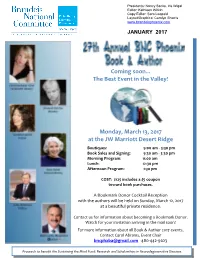

BNC-Phoenix Chapter

Presidents: Nancy Sacks, Iris Wigal Editor: Kathleen Witkin Copy Editor: Sara Leopold Layout/Graphics: Carolyn Sherris www.brandeisphoenix.com JANUARY 2017 Coming soon... The Best Event in the Valley! Monday, March 13, 2017 at the JW Marriott Desert Ridge Boutiques: 9:00 am - 3:30 pm Book Sales and Signing: 9:30 am - 3:30 pm Morning Program: 11:00 am Lunch: 12:30 pm Afternoon Program: 1:30 pm COST: $125 includes a $5 coupon toward book purchases. A Bookmark Donor Cocktail Reception with the authors will be held on Sunday, March 12, 2017 at a beautiful private residence. Contact us for information about becoming a Bookmark Donor. Watch for your invitation arriving in the mail soon! For more information about all Book & Author 2017 events, Contact Carol Abrams, Event Chair [email protected] 480-442-9623 Proceeds to benefit the Sustaining the Mind Fund: Research and Scholarships in Neurodegenerative Diseases JANUARY 2017 BNC PHOENIX CHAPTER PAGE 2 Co-Presidents’ Message Dear BNC Friends and Colleagues: We wish you and yours a happy, healthy and prosperous New Year. Looking back on 2016, we would like to thank our tireless volunteers and loyal members who have supported our chapter's fundraising on behalf of Brandeis University. Their efforts have made the following activities successful: summer camp, study groups, amazing events such as the beautiful Fall luncheon, the "Evening with Chris Caldwell," the wonderful dinner theater party and the canasta tournament. We also greatly appreciate their many donations to the Brandeis library, scholarship and the Sustaining the Mind funds. In 2017, there are so many more opportunities to support our chapter's mission to raise funds for Brandeis University. -

NYSBA Entertainment, Arts and Sports Law Journal | Spring 2014 | Vol

NYSBA SPRING 2014 | VOL. 25 | NO. 1 Entertainment, Arts and Sports Law Journal A publication of the Entertainment, Arts and Sports Law Section of the New York State Bar Association Concussion Litigation in the NHL; Is It Time to Pay College Athletes?; Bullying in Sports; The Anti-Flopping Policy in the NBA; and Much More WWW.NYSBA.ORG/EASL NEW YORK STATE BAR ASSOCIATION Section Members get 20% discount* with coupon code In The Arena: PUB2140N A Sports Law Handbook Co-sponsored by the New York State Bar Association and the Entertainment, Arts and Sports Law Section As the world of professional athletics has become more competitive and the issues more complex, so has the need for more reliable representation in the fi eld of sports law. Written by dozens of sports law attorneys and medical professionals, In the Arena: A Sports Law Handbook is a refl ection of the multiple issues that face athletes and the attorneys who represent them. Included in this book are chapters on representing professional athletes, NCAA enforcement, advertising, sponsorship, intellectual property rights, doping, concussion-related issues, Title IX and dozens of useful appendices. Table of Contents Intellectual Property Rights and Endorsement Agreements How Trademark Protection Intersects with the Athlete’s Right of Publicity EDITORS Collective Bargaining in the Big Three Elissa D. Hecker, Esq. Agency Law David Krell, Esq. Sports, Torts and Criminal Law PRODUCT INFO AND PRICES Role of Advertising and Sponsorship in the Business of Sports 2013 | 574 pages | softbound Doping in Sport: A Historical and Current Perspective | PN: 4002 Athlete Concussion-Related Issues Non-Members $80 Concussions—From a Neuropsychological and Medical Perspective NYSBA Members $65 In-Arena Giveaways: Sweepstakes Law Basics and Compliance Issues Order multiple titles to take advantage of our low fl at rate shipping charge of $5.95 per order, regardless Navigating the NCAA Enforcement Process of the number of items shipped. -

Walden Tells Jobs Foundation Economic

70 years Ago Today •Cherryville bats prevent WHS bid for ‘three-peat.’ June 6, 1944 •Cherryville cops opener D-Day with seventh-inning walk- off hit. The Invasion of Normandy Sports See page 1-B. ThePublished News since 1890 every Monday and Thursday Reporterfor the County of Columbus and her people. Monday, June 6, 2016 Second verdict Volume 125, Number 98 Whiteville, North Carolina sticks, Gore 75 Cents receives life nJuror who wavered after first ver- dict strong and forceful in her re- Inside sponses when individually polled as to her second verdict. 2-A By BOB HIGH •County to adopt Staff Writer budget; to ask to join state health plan at It took an extra 23 hours, but this time all 12 jurors individually confirmed by voice their tonight’s meeting. verdict that sent Ken- neth Harold Gore Jr., 3-A 32, to prison for life in •Cast of WCHS’s his first-degree murder ‘Annie’ experiences trial. No members of ‘humbling’ experi- Gore’s family attended ence at show’s finale. the session Thursday that ended at 11:10 a.m. Gore was passive again Thursday and didn’t Kenneth Gore look at the jurors as the courtroom clerk asked if the verdict the jury foreman returned was their verdict, and if it was still their decision. Each juror answered the questions with two quick “Yes” answers, including the woman who changed her mind Wednesday after an outburst of cursing and a tirade directly at Staff photo by FULLER ROYAL them by at least three members of Gore’s family. -

NOMINEES for the 31St ANNUAL NEWS & DOCUMENTARY EMMY® AWARDS ANNOUNCED by the NATIONAL ACADEMY of TELEVISION ARTS &

NOMINEES FOR THE 31st ANNUAL NEWS & DOCUMENTARY EMMY ® AWARDS ANNOUNCED BY THE NATIONAL ACADEMY OF TELEVISION ARTS & SCIENCES Winners to be announced on September 27th at Frederick P. Rose Hall, Home of Jazz at Lincoln Center Frederick Wiseman to Receive Lifetime Achievement Award New York, N.Y. – July 15, 2010 – Nominations for the 31st Annual News and Documentary Emmy ® Awards were announced today by the National Academy of Television Arts & Sciences (NATAS). The News & Documentary Emmy ® Awards will be presented on Monday, September 27 at a ceremony at Frederick P. Rose Hall, Home of Jazz at Lincoln Center, located in the Time Warner Center in New York City. The event will be attended by more than 1,000 television and news media industry executives, news and documentary producers and journalists. Emmy ® Awards will be presented in 41 categories, including Breaking News, Investigative Reporting, Outstanding Interview, and Best Documentary, among others. “From the ongoing wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, to the struggling American economy, to the inauguration of Barack Obama, 2009 was a significant year for major news stories,” said Bill Small, Chairman of the News & Documentary Emmy ® Awards. “The journalists and documentary filmmakers nominated this year have educated viewers in understanding some of the most compelling issues of our time, and we salute them for their efforts.” This year’s prestigious Lifetime Achievement Award will be given to Frederick Wiseman, one of the most accomplished documentarians in the history of the medium. In a career spanning almost half a century, Wiseman has produced, directed and edited 38 films. His documentaries comprise a chronicle of American life unmatched by perhaps any other filmmaker. -

The Rhythm of the Void

Jay Plaat S4173538 Master Thesis MA Creative Industries Radboud University Nijmegen, 2015-2016 Supervisor: dr. Natascha Veldhorst Second reader: dr. László Munteán The Rhythm of the Void On the rhythm of any-space-whatever in Bresson, Tarkovsky and Winterbottom Index Abstract 1 Introduction 2 Chapter 1 The Autonomous Cinematic Space Discourse (Or How Space Differs in Emptiness) 16 Chapter 2 Cinematic Rhythm 26 Chapter 3 The Any-Space-Whatever without Borders (Or Why Bresson Secretly Made Lancelot du Lac for People Who Can’t See) 37 Chapter 4 The Neutral, Onirosigns and Any-Body-Whatevers in Nostalghia 49 Chapter 5 The Any-Space-Whatever-Anomaly of The Face of an Angel (Or Why the Only True Any-Space-Whatever Is a Solitary One) 59 Conclusion 68 Appendix 72 Bibliography, internet sources and filmography 93 Abstract This thesis explores the specific rhythmic dimensions of Gilles Deleuze’s concept of any- space-whatever, how those rhythmic dimensions function and what consequences they have for the concept of any-space-whatever. Chapter 1 comprises a critical assessment of the autonomous cinematic space discourse and describes how the conceptions of the main contributors to this discourse (Balázs, Burch, Chatman, Perez, Vermeulen and Rustad) differ from each other and Deleuze’s concept. Chapter 2 comprises a delineation of cinematic rhythm and its most important characteristics. Chapters 3, 4 and 5 comprise case study analyses of Robert Bresson’s Lancelot du Lac, Andrei Tarkovsky’s Nostalghia and Michael Winterbottom’s The Face of an Angel, in which I coin four new additions to the concept of any-space-whatever. -

Congress, the Solicitor General, and the Path of Reapportionment Litigation Michael E

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Case Western Reserve University School of Law Case Western Reserve Law Review Volume 62 | Issue 4 2012 Congress, the Solicitor General, and the Path of Reapportionment Litigation Michael E. Solimine Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.case.edu/caselrev Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Michael E. Solimine, Congress, the Solicitor General, and the Path of Reapportionment Litigation, 62 Case W. Res. L. Rev. 1109 (2012) Available at: https://scholarlycommons.law.case.edu/caselrev/vol62/iss4/10 This Symposium is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Journals at Case Western Reserve University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Case Western Reserve Law Review by an authorized administrator of Case Western Reserve University School of Law Scholarly Commons. CONGRESS, THE SOLICITOR GENERAL, AND THE PATH OF REAPPORTIONMENT LITIGATION Michael E. Solimine† ABSTRACT The Supreme Court’s decision in Baker v. Carr unleashed the Reapportionment Revolution, which was largely driven by litigation in the lower federal courts, with periodic additional guidance by the Court. That litigation continues to the present day, revived every decade by new census data and further complicated by the demands of the Voting Rights Act and other factors. Less appreciated has been the role of Congress and the president in influencing that litigation. Baker was initially quite controversial in some circles, and that hostility was manifested by bills introduced in Congress that would have restricted the impact of the case. -

Patriotic Cut Above the Rest

AutoMatters & More Movies Around Town Sailboat racing, Sherlock Holmes, Art in Split, La La Land, The Bye Bye Man, xXx: Comic Fest, Monster Jam, 5 K Paw Walk, Motion at Reuben H. Fleet Science Center. The Return of Xander Cage, Monster Trucks The Ultimate Wine Run, WWE Live. See page 17 See page 21 See page 22 Navy Marine Corps Coast Guard Army Air Force AT AT EASE ARMED FORCES DISPATCHSan Diego Navy/Marine Corps Dispatch www.armedforcesdispatch.com 619.280.2985 FIFTY SIXTH YEAR NO. 36 Serving active duty and retired military personnel, veterans and civil service employees THURSDAY, FEBRUARY 16, 2017 PATRIOTIC Flight operations at NAS North Island by MC1 Travis Alston he mission of the Navy is to maintain, train and equip com- Tbat-ready Naval forces capable of winning wars, deterring CUT ABOVE aggression and maintaining freedom of the seas. The Navy is unique NB San Diego: in that it fulfills a broad role that encompasses everything from combat to peacekeeping to humanitarian assistance. A primary way Shore-based the Navy does this is by provid- THE REST ing firepower and support from top galley the air. by Ed Wright With this demanding task WASHINGTON - Naval in mind, it is vital that aviators Base San Diego and Joint are trained on the most techno- Expeditionary Base Little logically advanced aircraft in Creek-Fort Story, repre- the world, and on ranges and senting Navy Installations areas that allow them to “train Command galleys, were an- In February 1948 the like you fight.” One area that nounced by the secretary of world’s fastest carrier- requires dedicated and consistent the Navy as the winners of based jet aircraft, the training is preparing to land on the 2017 Captain Edward F. -

31St Annual News & Documentary Emmy Awards

NATIONAL ACADEMY OF TELEVISION ARTS & SCIENCES 31st Annual News & Documentary EMMY AWARDS CONGRATULATES THIS YEAR’S NEWS & DOCUMENTARY EMMY® NOMINEES AND HONOREES WEEKDAYS 7/6 c CONGRATULATES OUR NEWS & DOCUMENTARY EMMY® NOMINEES Outstanding Continuing Coverage of a News Story in a Regularly Scheduled Newscast “Inside Mexico’s Drug Wars” reported by Matthew Price “Pakistan’s War” reported by Orla Guerin WEEKDAYS 7/6 c 31st ANNUAL NEWS & DOCUMENTARY EMMY ® AWARDS LIFETIME ACHIEVEMENT / FREDERICK WISEMAN CHAIRMAN’S AWARD / PBS NEWSHOUR EMMY®AWARDS PRESENTED IN 39 CATEGORIES NOMINEES NBC News salutes our colleagues for the outstanding work that earned 22 Emmy Nominations st NATIONAL ACADEMY OF TELEVISION CUSTOM 5 ARTS & SCIENCES / ANNUAL NEWS & SUPPLEMENT 31 DOCUMENTARY / EMMY AWARDS / NEWSPRO 31st Annual News & Documentary Letter From the Chairman Emmy®Awards Tonight is very special for all of us, but especially so for our honorees. NATAS Presented September 27, 2010 New York City is proud to honor “PBS NewsHour” as the recipient of the 2010 Chairman’s Award for Excellence in Broadcast Journalism. Thirty-five years ago, Robert MacNeil launched a nightly half -hour broadcast devoted to national and CONTENTS international news on WNET in New York. Shortly thereafter, Jim Lehrer S5 Letter from the Chairman joined the show and it quickly became a national PBS offering. Tonight we salute its illustrious history. Accepting the Chairman’s Award are four S6 LIFETIME ACHIEVEMENT dedicated and remarkable journalists: Robert MacNeil and Jim Lehrer; HONOREE - FREDERICK WISEMAN longtime executive producer Les Crystal, who oversaw the transition of the show to an hourlong newscast; and the current executive producer, Linda Winslow, a veteran of the S7 Un Certain Regard By Marie-Christine de Navacelle “NewsHour” from its earliest days.