Getting to the Territorial Endgame of an Israeli-Palestinian Peace Settlement

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Area C of the West Bank: Key Humanitarian Concerns Update August 2014

UNITED NATIONS Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs occupied Palestinian territory AREA C OF THE WEST BANK: KEY HUMANITARIAN CONCERNS UPDATE AUGUST 2014 KEY FACTS � Over 60 percent of the West Bank is considered Area C, where Israel retains near exclusive control, including over law enforcement, planning and construction. � An estimated 300,000 Palestinians live in Area C in about 530 residential areas, 241 of which are located entirely in Area C. � Some 341,000 Israeli settlers live in some 135 settlements and about 100 outposts in Area C, in contravention of international law; the settlements’ municipal area (the area available for their expansion) is nine times larger than their current fenced/patrolled area. � 70% of Area C is included within the boundaries of the regional councils of Israeli settlements (as distinct from the municipal boundaries) and is off-limits for Palestinian use and development. � Palestinian construction in 29% of Area C is heavily restricted; only approximately 1% of Area C has been planned for Palestinian development. � 6,200 Palestinians reside in 38 communities located in parts of Area C that have been designated as “firing zones” for military training, increasing their vulnerabilities and risk of displacement. � In 2013, 565 Palestinian-owned structures in Area C, including 208 residential structures, were demolished due to lack of Israeli-issued permits, displacing 805 people, almost half of them children. � More than 70% of communities located entirely or mostly in Area C are not connected to the water network and rely on tankered water at vastly increased cost; water consumption in some of these communities is as low as 20 litres per capita per day, one-fifth of the WHO’s recommendation. -

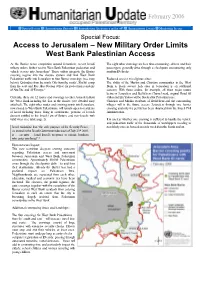

Access to Jerusalem – New Military Order Limits West Bank Palestinian Access

February 2006 Special Focus Humanitarian Reports Humanitarian Assistance in the oPt Humanitarian Events Monitoring Issues Special Focus: Access to Jerusalem – New Military Order Limits West Bank Palestinian Access As the Barrier nears completion around Jerusalem, recent Israeli The eight other crossings are less time-consuming - drivers and their military orders further restrict West Bank Palestinian pedestrian and passengers generally drive through a checkpoint encountering only vehicle access into Jerusalem.1 These orders integrate the Barrier random ID checks. crossing regime into the closure system and limit West Bank Palestinian traffic into Jerusalem to four Barrier crossings (see map Reduced access to religious sites: below): Qalandiya from the north, Gilo from the south2, Shu’fat camp The ability of the Muslim and Christian communities in the West from the east and Ras Abu Sbeitan (Olive) for pedestrian residents Bank to freely access holy sites in Jerusalem is an additional of Abu Dis, and Al ‘Eizariya.3 concern. With these orders, for example, all three major routes between Jerusalem and Bethlehem (Tunnel road, original Road 60 Currently, there are 12 routes and crossings to enter Jerusalem from (Gilo) and Ein Yalow) will be blocked for Palestinian use. the West Bank including the four in the Barrier (see detailed map Christian and Muslim residents of Bethlehem and the surrounding attached). The eight other routes and crossing points into Jerusalem, villages will in the future access Jerusalem through one barrier now closed to West Bank Palestinians, will remain open to residents crossing and only if a permit has been obtained from the Israeli Civil of Israel including those living in settlements, persons of Jewish Administration. -

BARRIER2005 02-05 P3.Indd

United Nations Nations Unies The Humanitarian Impact of the West Bank Barrier on Palestinian Communities March 2005 Update No. 5 A report to the Humanitarian Emergency Policy Group (HEPG), compiled by the United Nations Office for Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) and the United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees (UNRWA) in the occupied Palestinian territory.1 Men crossing a gap in the unfinished Barrier in Abu Dis, Western side of Jerusalem (2005) Table of Contents 1 Findings and Overview Introduction .........................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................1 Map | West Bank Barrier: New Route Comparison ..............................................................................................................................................2 Overview and Key Developments of the Latest Barrier Route ..........................................................................................................3 Map | West Bank Barrier Projections: Preliminary Overview ..............................................................................................................4 Background ...........................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................7 -

November 2014 Al-Malih Shaqed Kh

Salem Zabubah Ram-Onn Rummanah The West Bank Ta'nak Ga-Taybah Um al-Fahm Jalameh / Mqeibleh G Silat 'Arabunah Settlements and the Separation Barrier al-Harithiya al-Jalameh 'Anin a-Sa'aidah Bet She'an 'Arrana G 66 Deir Ghazala Faqqu'a Kh. Suruj 6 kh. Abu 'Anqar G Um a-Rihan al-Yamun ! Dahiyat Sabah Hinnanit al-Kheir Kh. 'Abdallah Dhaher Shahak I.Z Kfar Dan Mashru' Beit Qad Barghasha al-Yunis G November 2014 al-Malih Shaqed Kh. a-Sheikh al-'Araqah Barta'ah Sa'eed Tura / Dhaher al-Jamilat Um Qabub Turah al-Malih Beit Qad a-Sharqiyah Rehan al-Gharbiyah al-Hashimiyah Turah Arab al-Hamdun Kh. al-Muntar a-Sharqiyah Jenin a-Sharqiyah Nazlat a-Tarem Jalbun Kh. al-Muntar Kh. Mas'ud a-Sheikh Jenin R.C. A'ba al-Gharbiyah Um Dar Zeid Kafr Qud 'Wadi a-Dabi Deir Abu Da'if al-Khuljan Birqin Lebanon Dhaher G G Zabdah לבנון al-'Abed Zabdah/ QeiqisU Ya'bad G Akkabah Barta'ah/ Arab a-Suweitat The Rihan Kufeirit רמת Golan n 60 הגולן Heights Hadera Qaffin Kh. Sab'ein Um a-Tut n Imreihah Ya'bad/ a-Shuhada a a G e Mevo Dotan (Ganzour) n Maoz Zvi ! Jalqamus a Baka al-Gharbiyah r Hermesh Bir al-Basha al-Mutilla r e Mevo Dotan al-Mughayir e t GNazlat 'Isa Tannin i a-Nazlah G d Baqah al-Hafira e The a-Sharqiya Baka al-Gharbiyah/ a-Sharqiyah M n a-Nazlah Araba Nazlat ‘Isa Nazlat Qabatiya הגדה Westהמערבית e al-Wusta Kh. -

NABI SAMWIL Saint Andrew’S Evangelical Church - (Protestant Hall) Ramallah - West Bank - Palestine 2018

About Al-Haq Al-Haq is an independent Palestinian non-governmental human rights organisation based in Ramallah, West Bank. Established in 1979 to protect and promote human rights and the rule of law in the Occupied Palestinian Territory (OPT), the organisation has special consultative status with the UN Economic and Social Council. Al-Haq documents violations of the individual and collective rights of Palestinians in the OPT, regardless of the identity of the perpetrator, and seeks to end such breaches by way of advocacy before national and international mechanisms and by holding the violators accountable. The organisation conducts research; prepares reports, studies and interventions on the breaches of international human rights and humanitarian law in the OPT; and undertakes advocacy before local, regional and international bodies. Al-Haq also cooperates with Palestinian civil society organisations and governmental institutions in order to ensure that international human rights standards are reflected in Palestinian law and policies. The organisation has a specialised international law library for the use of its staff and the local community. Al-Haq is also committed to facilitating the transfer and exchange of knowledge and experience in international humanitarian and human rights law on the local, regional and international levels through its Al-Haq Center for Applied International Law. The Center conducts training courses, workshops, seminars and conferences on international humanitarian law and human rights for students, lawyers, journalists and NGO staff. The Center also hosts regional and international researchers to conduct field research and analysis of aspects of human rights and IHL as they apply in the OPT. -

The Palestinian Economy in East Jerusalem, Some Pertinent Aspects of Social Conditions Are Reviewed Below

UNITED N A TIONS CONFERENC E ON T RADE A ND D EVELOPMENT Enduring annexation, isolation and disintegration UNITED NATIONS CONFERENCE ON TRADE AND DEVELOPMENT Enduring annexation, isolation and disintegration New York and Geneva, 2013 Notes The designations employed and the presentation of the material do not imply the expression of any opinion on the part of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area, or of authorities or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. ______________________________________________________________________________ Symbols of United Nations documents are composed of capital letters combined with figures. Mention of such a symbol indicates a reference to a United Nations document. ______________________________________________________________________________ Material in this publication may be freely quoted or reprinted, but acknowledgement is requested, together with a copy of the publication containing the quotation or reprint to be sent to the UNCTAD secretariat: Palais des Nations, CH-1211 Geneva 10, Switzerland. ______________________________________________________________________________ The preparation of this report by the UNCTAD secretariat was led by Mr. Raja Khalidi (Division on Globalization and Development Strategies), with research contributions by the Assistance to the Palestinian People Unit and consultant Mr. Ibrahim Shikaki (Al-Quds University, Jerusalem), and statistical advice by Mr. Mustafa Khawaja (Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics, Ramallah). ______________________________________________________________________________ Cover photo: Copyright 2007, Gugganij. Creative Commons, http://commons.wikimedia.org (accessed 11 March 2013). (Photo taken from the roof terrace of the Austrian Hospice of the Holy Family on Al-Wad Street in the Old City of Jerusalem, looking towards the south. In the foreground is the silver dome of the Armenian Catholic church “Our Lady of the Spasm”. -

Public Companies Profiting from Illegal Israeli Settlements on Palestinian Land

Public Companies Profiting from Illegal Israeli Settlements on Palestinian Land Yellow highlighting denotes companies held by the United Methodist General Board of Pension and Health Benefits (GBPHB) as of 12/31/14 I. Public Companies Located in Illegal Settlements ACE AUTO DEPOT LTD. (TLV:ACDP) - owns hardware store in the illegal settlement of Ma'ale Adumim http://www.ace.co.il/default.asp?catid=%7BE79CAE46-40FB-4818-A7BF-FF1C01A96109%7D, http://www.machat.co.il/businesses.php, http://www.nytimes.com/2007/03/14/world/middleeast/14israel.html?_r=3&oref=slogin&oref=slogin&, http://investing.businessweek.com/research/stocks/snapshot/snapshot.asp?ticker=ACDP:IT ALON BLUE SQUARE ISRAEL LTD. (NYSE:BSI) - has facilities in the Barkan and Atarot Industrial Zones and operates supermarkets in many West Bank settlements www.whoprofits.org/company/blue- square-israel, http://www.haaretz.com/business/shefa-shuk-no-more-boycotted-chain-renamed-zol-b-shefa-1.378092, www.bsi.co.il/Common/FilesBinaryWrite.aspx?id=3140 AVGOL INDUSTRIES 1953 LTD. (TLV:AVGL) - has a major manufacturing plant in the Barkan Industrial Zone http://www.unitedmethodistdivestment.com/ReportCorporateResearchTripWestBank2010FinalVersion3.pdf (United Methodist eyewitness report), http://panjiva.com/Avgol-Ltd/1370180, http://www.haaretz.com/print-edition/business/avgol- sees-bright-future-for-nonwoven-textiles-in-china-1.282397 AVIS BUDGET GROUP INC. (NASDAQ:CAR) - leases cars in the illegal settlements of Beitar Illit and Modi’in Illit http://rent.avis.co.il/en/pages/car_rental_israel_stations, http://www.carrentalisrael.com/car-rental- israel.asp?refr= BANK HAPOALIM LTD. (TLV:POLI) - has branches in settlements; provides financing for housing projects in illegal settlements, mortgages for settlers, and financing for the Jerusalem light rail project, which connects illegal settlements with Jerusalem http://www.haaretz.com/print-edition/business/bank-hapoalim-to-lead-financing-for-jerusalem-light-rail-line-1.97706, http://www.whoprofits.org/company/bank-hapoalim BANK LEUMI LE-ISRAEL LTD. -

Terminals, Agricultural Crossings and Gates

Terminals, Agricultural Crossings and Gates Umm Dar Terminals ’AkkabaDhaher al ’Abed Zabda Agricultural Gate (gap in the Wall) Controlled access through the Wall has been promised by the GOI to Ya’bad Wall (being finalised or complete) Masqufet al Hajj Mas’ud enable movement between Israel and the West Bank for Palestinian West Bank boundary/Green Line (estimate) Qaffin Imreiha populations who are either trapped in enclaves or isolated from their Road network agricultural lands. Palestinian Locality Hermesh Israeli Settlement Nazlat ’Isa An Nazla al Wusta According to Israel's State Attorney's office, five controlled crossings or NOTE: Agricultural Gate locations have been Baqa ash Sharqiya collected from field visits by OCHA staff and An Nazla ash Sharqiya terminals similar to the Erez terminal in northern Gaza will be built along information partners. The Wall trajectory is based on satellite imagery and field visits. An Nazla al Gharbiya the Wall. The Government of Israel recently decided that the Israeli Airport Authority will plan and operate the terminals. One of the main terminals between Israel and the West Bank appears to be being built Zeita Seida near Taibeh, 75 acres (300 dunums)35 in a part of Tulkarm City 36 Kafr Ra’i considered area A. ’Attil ’Illar The remaining terminals/control points are designated for areas near Jenin, Atarot north of Jerusalem, north of the Gush Etzion and near Deir al Ghusun Tarkumiyeh settlement bloc. Al Jarushiya Bal’a Agricultural Crossings and Gates Iktaba Al ’Attara The State Attorney's Office has stated that 26 agricultural gates will be TulkarmNur Shams Camp established along the length of the Wall to allow Palestinian farmers who Kafr Rumman have land west of the Wall, to cross. -

78% of Construction Was in “Isolated Settlements”*

Peace Now’s Annual Settlement Construction Report for 2017 Construction Starts in Settlements were 17% Above Average in 2017 78% of Construction was in “Isolated Settlements”* Settlement Watch, Peace Now Key findings – Construction in the West Bank, 2017 (East Jerusalem excluded) 1 According to Peace Now's count, 2,783 new housing units began construction in 2017, around 17% higher than the yearly average rate since 2009.2 78% (2,168 housing units) of the new construction was in settlements east of the proposed Geneva Initiative border, i.e. settlements that are likely to be evicted in a two-state agreement. 36% (997 housing units) of the new construction was in areas that are east of the route of the separation barrier. Another 46% (1,290 units) was between the built and the planned route of the fence. Only 18% was west of the built fence. At least 10% (282 housing units) of the construction was illegal according to the Israeli laws applied in the Occupied Territories (regardless of the illegality of all settlements according to the international law). Out of those, 234 units (8% of the total construction) were in illegal outposts. The vast majority of the new construction, 91% (2,544 housing units), was for permanent structures, while that the remainder 9% were new housing units in the shape of mobile homes both in outposts and in settlements. 68 new public buildings (such as schools, synagogues etc.) started to be built, alongside 69 structures for industry or agriculture. Advancement of Plans and Tenders (January-December 2017) 6,742 housing units were advanced through promotions of plans for settlements, in 59 different settlements (compared to 2,657 units in 2016). -

English/Deportation/Statistics

International Court of Justice Advisory Opinion Proceedings On Legal Consequences of the Construction of a Wall in the Occupied Palestinian Territory Palestine Written Statement (30 January 2004) And Oral Pleading (23 February 2004) Preface 1. In October of 2003, increasing concern about the construction by Israel, the occupying Power, of a Wall in the Occupied Palestinian Territory, including East Jerusalem, in departure from the Armistice Line of 1949 (the Green Line) and deep into Palestinian territory, brought the issue to the forefront of attention and debate at the United Nations. The Wall, as it has been built by the occupying Power, has been rapidly expanding as a regime composed of a complex physical structure as well as practical, administrative and other measures, involving, inter alia, the confiscation of land, the destruction of property and countless other violations of international law and the human rights of the civilian population. Israel’s continued and aggressive construction of the Wall prompted Palestine, the Arab Group, the Non-Aligned Movement (NAM) and the Organization of the Islamic Conference (OIC) to convey letters to the President of the United Nations Security Council in October of 2003, requesting an urgent meeting of the Council to consider the grave violations and breaches of international law being committed by Israel. 2. The Security Council convened to deliberate the matter on 14 October 2003. A draft resolution was presented to the Council, which would have simply reaffirmed, inter alia, the principle of the inadmissibility of the acquisition of territory by force and would have decided that the “construction by Israel, the occupying Power, of a wall in the Occupied Territories departing from the armistice line of 1949 is illegal under relevant provisions of international law and must be ceased and reversed”. -

H.E. Mr. Ariel Sharon Prime Minister of the State of Israel

Statement by H.E. Mr. Ariel Sharon Prime Minister of the State of Israel High-Level Plenary Meeting of the 60'h Session of the General Assembly United Nations, New York 15 September 2005 Translation Prime Minister Ariel Sharon' Speech at the United Nations Assembly September 15, 2005 My friends and colleagues, heads and representatives of the UN member states, I arrived here from Jerusalem, the capital of the Jewish people for over 3,000 years, and the undivided and eternal capital of the State of Israel. At the outset, I would like to express the profound feelings of empathy of the people of Israel for the American nation, and our sincere condolences to the families who lost their loved ones. I wish to encourage my friend, President George Bush, and the American people, in their determined effo rts to assist the victims of the hur ricane and rebuild the ruins after the destruction. The State of Israel, which the United States stood beside at times of trial, is ready to extend any assistance at its disposal in this immense humanitarian mission. Ladies and Gentlemen, I stand before you at the gate of nations as a Jew and as a citizen of the free and sovereign State of Israel, a proud representative of an ancient people, whose numbers are few, but whose contribution to civilization and to the values of ethics, justice and faith, surrounds the world and encompasses history. The Jewish people have a long memory, the memory which united the exiles of Israel for thousands of years: a memory which has its origin in G-d's commandment to our forefather Abraham: "Go forth!" and continued with the receiving of the Torah at the foot of Mount Sinai and the wanderings of the children of Israel in the desert, led by Moses on their journey to the promised land, the land of Israel. -

Walking in the Footsteps of Jesus “Walking with Jesus Every Day” Sermon Preached by Jeff Huber April 6-7, 2013 at First United Methodist Church - Durango

THEME: The Way: Walking in the Footsteps of Jesus “Walking With Jesus Every Day” Sermon preached by Jeff Huber April 6-7, 2013 at First United Methodist Church - Durango Luke 24: 28-34 28 By this time they were nearing Emmaus and the end of their journey. Jesus acted as if he were going on, 29 but they begged him, “Stay the night with us, since it is getting late.” So he went home with them. 30 As they sat down to eat, he took the bread and blessed it. Then he broke it and gave it to them. 31 Suddenly, their eyes were opened, and they recognized him. And at that moment he disappeared! 32 They said to each other, “Didn’t our hearts burn within us as he talked with us on the road and explained the Scriptures to us?” 33 And within the hour they were on their way back to Jerusalem. There they found the eleven disciples and the others who had gathered with them, 34 who said, “The Lord has really risen! He appeared to Peter.” VIDEO Walking with Jesus Every Day Sermon Starter SLIDE Walking with Jesus Every Day (Use The Way background) Today we conclude our series of sermons on The Way: Walking in the Footsteps of Jesus. I invite you to take out of your bulletin your Message Notes and your Meditation Moments. The Message Notes have our Scripture passage listed at the top of them and then below that you will find some space to take notes and my hope is that you might hear something today that you would want to remember and you would write that down.