Reproductive and Behavioral Aspects of Partridges (Rhynchotus Rufescens) Using Different Mating Strategies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Northwest Argentina (Custom Tour) 13 – 24 November, 2015 Tour Leader: Andrés Vásquez Co-Guided by Sam Woods

Northwest Argentina (custom tour) 13 – 24 November, 2015 Tour leader: Andrés Vásquez Co-guided by Sam Woods Trip Report by Andrés Vásquez; most photos by Sam Woods, a few by Andrés V. Elegant Crested-Tinamou at Los Cardones NP near Cachi; photo by Sam Woods Introduction: Northwest Argentina is an incredible place and a wonderful birding destination. It is one of those locations you feel like you are crossing through Wonderland when you drive along some of the most beautiful landscapes in South America adorned by dramatic rock formations and deep-blue lakes. So you want to stop every few kilometers to take pictures and when you look at those shots in your camera you know it will never capture the incredible landscape and the breathtaking feeling that you had during that moment. Then you realize it will be impossible to explain to your relatives once at home how sensational the trip was, so you breathe deeply and just enjoy the moment without caring about any other thing in life. This trip combines a large amount of quite contrasting environments and ecosystems, from the lush humid Yungas cloud forest to dry high Altiplano and Puna, stopping at various lakes and wetlands on various altitudes and ending on the drier upper Chaco forest. Tropical Birding Tours Northwest Argentina, Nov.2015 p.1 Sam recording memories near Tres Cruces, Jujuy; photo by Andrés V. All this is combined with some very special birds, several endemic to Argentina and many restricted to the high Andes of central South America. Highlights for this trip included Red-throated -

Rhynchotus Rufescens Is Known Only Mountainridges in the Easternandes of Bolivia and from a Small Number of Museumspecimens

July1996] ShortCommunications andCommentaries 695 SHARP,D. E., AND J. T. LOKEMOEN.1987. A decoy choice in Mallards (Anas platyrhynchos).Behav- trap for breeding-seasonMallards in North Da- iour 115:127-141. kota. Journal of Wildlife Management 51:711- WEIDMANN,U., AND J. DARLEY. 1971. The role of the 715. femalein the socialdisplay of Mallards.Animal TITMAN,R. D. 1983. Spacingand three-bird flights Behaviour 19:287-298. of Mallards breeding in pothole habitat. Cana- dian Journalof Zoology 61:839-847. Received11 April 1994,accepted 5 September1994. WEIDMANN,U. 1990. Plumage quality and mate The Auk 113(3):695-697, 1996 Distinctive Song of Highland Form mact•licoIIfsof the Red-winged Tinamou (Rhynchotus rulescerts):Evidence for SpeciesRank SJOERDMAIJER • Ter Meulenplantsoen20, 7524 CA Enschede,The Netherlands The highland subspeciesmaculicollis of the Red- Rhynchotusrufescens maculicollis occurs on grassy winged TinamouRhynchotus rufescens is known only mountainridges in the easternAndes of Bolivia and from a small number of museumspecimens. No life northwesternArgentina at 1,000to 3,500m (Fjeldsl history data have been published. Herein I describe and Krabbe 1990). The other subspeciesof this bird the highly distinctivesong of this form. The songwas are widely distributed in grasslandhabitats south of a mysterioussound that I heard and tape recordedin the Amazon, from extreme southeastern Peru to cen- severallocalities in the BolivianAndes. I finallytracked tral Argentina,mostly in the lowlandsbut alsoin the down a singing bird in December 1993, near Inqui- highlands of easternBrazil (Sick 1993). sivi, departamentoLa Paz, Bolivia. A sonogramfrom Inquisivi and sonogramsof two different birds recorded near Vallegrande, departa- mento SantaCruz, are shown in FiguresIA, B, C. -

Paraguayan Mega! (Paul Smith)

“South America’s Ivorybill”, the Helmeted Woodpecker is a Paraguayan mega! (Paul Smith) PARAGUAY 15 SEPTEMBER – 2 OCTOBER 2017 LEADER: PAUL SMITH With just short of 400 birds and 17 mammals Paraguay once again proved why it is South America’s fastest growing birding destination. The "Forgotten Heart of South America", may still be an “off the beaten track” destination that appeals mainly to adventurous birders, but thanks to some easy walking, stunning natural paradises and friendly, welcoming population, it is increasingly becoming a “must visit” country. And there is no wonder, with a consistent record for getting some of South America’s super megas such as Helmeted Woodpecker, White-winged Nightjar, Russet-winged Spadebill and Saffron-cowled Blackbird, it has much to offer the bird-orientated visitor. Paraguay squeezes four threatened ecosystems into its relatively manageable national territory and this, Birdquest’s fourth trip, visits all of them. As usual the trip gets off to flyer in the humid and dry Chaco; meanders through the rarely-visited Cerrado savannas; indulges in a new bird frenzy in the megadiverse Atlantic Forest; and signs off with a bang in the Mesopotamian flooded grasslands of southern Paraguay. This year’s tour was a little earlier than usual, and we suffered some torrential rainstorms, but with frequent knee-trembling encounters with megas along the way it was one to remember. 1 BirdQuest Tour Report: Paraguay www.birdquest-tours.com Crakes would be something of a theme on this trip, and we started off with a belter in the pouring rain, the much sought after Grey-breasted Crake. -

Behavior of Boucard's Tinamou, Crypturellus Boucardi, in the Breeding Season

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1960 Behavior of Boucard's Tinamou, Crypturellus Boucardi, in the Breeding Season. Douglas Allan Lancaster Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Lancaster, Douglas Allan, "Behavior of Boucard's Tinamou, Crypturellus Boucardi, in the Breeding Season." (1960). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 630. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/630 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This dissertation has been microfilmed exactly as received Mic 60-5920 LANCASTER, Douglas Allan. BEHAVIOR OF BOUCARD'S TINAMOU, CRYPTURELLUS BQUCARDI, IN THE BREEDING SEASON. Louisiana State University, Ph.D., 1960 Z oology University Microfilms, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan BEHAVIOR OF BOUCARD'S TINAMOU, CRYPTURELLUS BQUCARDI. IN THE BREEDING SEASON A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural aid. Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of Zoology fey Douglas Allan Lancaster B.A., Carleton College, 1950 August, I960 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS -

Nothura Maculosa) Y Del Tinamú Alirrojo (Rhynchotus Rufescens) En Una Área Cinegética Del Rio Grande Do Sul (Brasil

ORNITOLOGIA NEOTROPICAL 10: 35–41, 1999 © The Neotropical Ornithological Society ABUNDANCIA DEL TINAMÚ MANCHADO (NOTHURA MACULOSA) Y DEL TINAMÚ ALIRROJO (RHYNCHOTUS RUFESCENS) EN UNA ÁREA CINEGÉTICA DEL RIO GRANDE DO SUL (BRASIL) Renato T. Pinheiro1,2 y Germán López1 1Departamento de Ecología, Universidad de Alicante, Ap. Correos 99, 03080, Alicante, España. E-mail: [email protected] 2Associação Brasileira para Conservação das Aves (PROAVES), Caixa Postal 08937, 70.312-970, Brasilia-DF, Brasil. Abstract. Abundance indexes (birds/km) of Spotted Nothura (Nothura maculosa) and Red-winged Tinamou (Rhynchotus rufescens) were obtained in 27 properties distributed among 10 municipalities in a game area in Rio Grande do Sul (Brazil). One transect (length 1 km) was made in native vegetation in each property in the pre-breeding period of 1993 (September) and in the post-breeding periods of 1993 and 1994 (April). Data were also gathered about the type of crops and farming management in the properties studied. Pool- ing data from all periods and properties, the abundance index for the Spotted Nothura was 7.3 birds/km while the Red-winged Tinamou was very scarce (0.025 birds/km). Abundance of the Spotted Nothura was greater in September 1993 than in April 1994. This was probably due to postbreeding dispersion from native vegetation areas to cultivated ones. A stepwise multiple regression analysis was performed for each period using the abundance index of Spotted Nothura as dependent variable. This analysis selected both in pre-breeding and in post-breeding periods the same two predictor variables. First, the abundance index of properties included within the distribution area of the "pampa" vegetation was greater than for properties included within "monte" or mixed vegetation areas. -

P0471-P0480.Pdf

ORNITOLOGIA NEOTROPICAL 16: 471–479, 2005 © The Neotropical Ornithological Society WALKING KINEMATICS PARAMETERS IN SOME PALEOGNATHOUS AND NEOGNATHOUS NEOTROPICAL BIRDS Anick Abourachid1, Elizabeth Höfling2, & Sabine Renous1 1USM302, Département d’Écologie et Gestion de la Biodiversité, Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle, CP 55, 57 rue Cuvier, 75231 Paris, Cedex 05, France. E-mail: [email protected] 2Departamento de Zoologia, Instituto de Biociências, Universidade de São Paulo, Rua do Matão, Travessa 14, n. 101, CEP 05508-900, São Paulo, Brazil. Resumo. – Parâmetros cinemáticos da marcha em aves paleognatas e neognatas neotropicais. – Foram estudados os parâmetros cinemáticos da marcha de tinamídeos (Tinamus solitarius, Crypturellus obsole- tus e Rhynchotus rusfescens) e cariamídeos (Cariama cristata e Chunga burmeisteri) com o objetivo de verificar se a duração da fase de elevação dos membros é um parâmetro discriminante para as aves paleognatas e neognatas. Os tinamídeos, assim como as ratitas, são aves paleognatas e os cariamídeos, que compartilham com as grandes ratitas a adaptação cursora, são neognatas. As mensurações dos ossos longos dos mem- bros posteriores, bem como a análise imagem por imagem de vídeo registrado em alta velocidade de aves marchando em condições normais, permitiram comparar a duração da fase de elevação dos membros em duas categorias funcionais: aves com os membros posteriores longos e esticados vs aquelas com membros posteriores curtos e flexionados. Foram também comparadas as aves pertencentes a dois grupos filogene- ticamente distintos: Neognathae vs Palaeognathae. Os resultados indicam que existe uma correlação entre a fase de elevação dos membros e os dois clados estudados: as paleognatas exibem uma fase mais longa do que as neognatas pertencentes à mesma categoria funcional. -

FIELD GUIDES BIRDING TOURS: Northwestern Argentina 2012

Field Guides Tour Report Northwestern Argentina 2012 Oct 17, 2012 to Nov 4, 2012 Dave Stejskal & Willy Perez For our tour description, itinerary, past triplists, dates, fees, and more, please VISIT OUR TOUR PAGE. One of the stars of the tour: a Diademed Sandpiper-Plover in the bofedal below Abra de Lizoite at about 13,800' on the last full day of birding on the tour! (Photo by guide Dave Stejskal) We pulled off yet another fabulous tour to beautiful and birdy Northwestern Argentina this year! The weather was very cooperative this year, with only a bit of rain in Cordoba and in the yungas forests of Jujuy, which didn't slow us down at all. If anything, it was a little too dry again this year, conforming to a longer trend that I've noted in the past ten years or so there. Despite the overall dryness, Laguna de Pozuelos had, rather surprisingly, more water in it than I've seen for many years! That change renewed my hope for many of the high elevation waterbirds breeding there this year. This tour is typically chock full of highlights, since we typically get just about every single specialty bird possible. We had a few 'dips' this year, like every year, but highlights were plentiful again. Cordoba gave up its special birds rather predictably, but we still enjoyed our looks at the 2 endemic cinclodes there, the scarce Salinas Monjita, Spot-winged Falconet, and that surprise Black-legged Seriema on our drive back to the main highway! Tucuman provided great encounters with Rufous-throated Dipper and Slender-tailed Woodstar, and a quartet of endemics: Yellow-striped Brush-Finch, White-browed Tapaculo, Bare-eyed Ground-Dove, and Tucuman Mountain-Finch. -

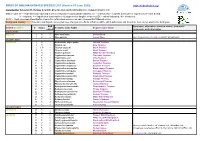

BIRDS of BOLIVIA UPDATED SPECIES LIST (Version 03 June 2020) Compiled By: Sebastian K

BIRDS OF BOLIVIA UPDATED SPECIES LIST (Version 03 June 2020) https://birdsofbolivia.org/ Compiled by: Sebastian K. Herzog, Scientific Director, Asociación Armonía ([email protected]) Status codes: R = residents known/expected to breed in Bolivia (includes partial migrants); (e) = endemic; NB = migrants not known or expected to breed in Bolivia; V = vagrants; H = hypothetical (observations not supported by tangible evidence); EX = extinct/extirpated; IN = introduced SACC = South American Classification Committee (http://www.museum.lsu.edu/~Remsen/SACCBaseline.htm) Background shading = Scientific and English names that have changed since Birds of Bolivia (2016, 2019) publication and thus differ from names used in the field guide BoB Synonyms, alternative common names, taxonomic ORDER / FAMILY # Status Scientific name SACC English name SACC plate # comments, and other notes RHEIFORMES RHEIDAE 1 R 5 Rhea americana Greater Rhea 2 R 5 Rhea pennata Lesser Rhea Rhea tarapacensis , Puna Rhea (BirdLife International) TINAMIFORMES TINAMIDAE 3 R 1 Nothocercus nigrocapillus Hooded Tinamou 4 R 1 Tinamus tao Gray Tinamou 5 H, R 1 Tinamus osgoodi Black Tinamou 6 R 1 Tinamus major Great Tinamou 7 R 1 Tinamus guttatus White-throated Tinamou 8 R 1 Crypturellus cinereus Cinereous Tinamou 9 R 2 Crypturellus soui Little Tinamou 10 R 2 Crypturellus obsoletus Brown Tinamou 11 R 1 Crypturellus undulatus Undulated Tinamou 12 R 2 Crypturellus strigulosus Brazilian Tinamou 13 R 1 Crypturellus atrocapillus Black-capped Tinamou 14 R 2 Crypturellus variegatus -

Redalyc.Morphology of Oesophagus and Crop of the Partrigde

Acta Scientiarum. Biological Sciences ISSN: 1679-9283 [email protected] Universidade Estadual de Maringá Brasil Rossi, Juliana Regina; Martinez Baraldi-Artoni, Silvana; Oliveira, Daniela; Cruz, Claudinei da; Sagula, Alex; Pacheco, Maria Rita; Lania de Araújo, Marcos Morphology of oesophagus and crop of the partrigde Rhynchotus rufescens (Tiramidae) Acta Scientiarum. Biological Sciences, vol. 28, núm. 2, abril-junio, 2006, pp. 165-168 Universidade Estadual de Maringá .png, Brasil Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=187115767012 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative Morphology of oesophagus and crop of the partrigde Rhynchotus rufescens (Tiramidae) Juliana Regina Rossi 1, Silvana Martinez Baraldi-Artoni 1*, Daniela Oliveira 2, Claudinei da Cruz 1, Alex Sagula 1, Maria Rita Pacheco 1 and Marcos Lania de Araújo 1 1Departamento de Morfologia e Fisiologia Animal, Faculdade de Ciências Agrárias e Veterinárias (FCAV), Universidade Estadual Paulista (Unesp), Rod. Acesso Paulo Donato Castellane, s/n, km 5, 14884-900, Jaboticabal, São Paulo, Brasil. 2Unidade Acadêmica de Garanhuns (UAG), Universidade Federal Rural de Pernambuco (UFRPE), Pernambuco, Brasil. *Author for correspondence. e-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT. Twenty adult partridges Rhynchotus rufescens were used to study the morphology of oesophagus and crop. Materials to the morphologic study were collected and lengths of the oesophagus and of the crop were measured. For histological study, fragments of the oesophagus and of the crop were stained routinely with Masson’s trichrome stain. -

(Aves: Tinamiformes, Tinamidae) from the Early-Middle Miocene of Argentina

Chandler, New Species of Tinamou PalArch’s Journal of Vertebrate Palaeontology, 9(2) (2012) A NEW SPECIES OF TINAMOU (AVES: TINAMIFORMES, TINAMIDAE) FROM THE EARLY-MIDDLE MIOCENE OF ARGENTINA Robert M. Chandler* * Department of Biological and Environmental Sciences, Georgia College and State Uni- versity, Milledgeville, GA 31061, [email protected] Robert M. Chandler. 2012. A New Species of Tinamou (Aves: Tinamiformes, Tinami- dae) from the Early-Middle Miocene of Argentina. – Palarch’s Journal of Vertebrate Palaeontology 9(2) (2012), 1-8. ISSN 1567-2158. 8 pages + 2 fi gures, 1 table. Keywords: fossil, Miocene, tinamou, Crypturellus, Argentina ABSTRACT A new species of tinamou from the early-middle Miocene (Santacrusian), Santa Cruz Forma- tion of Argentina is named. The new species is approximately 16 million year old and has an affi nity with the modern genus Crypturellus based on the unique characteristics of the humerus, hence, the designation aff. Crypturellus. Fossil species and the zooarchaeological record of modern tinamous are given. Introduction Among the fossils collected by Brown is an almost complete left humerus of a tinamou. In In 1898-1899, Barnum Brown, assistant curator recent years, tinamou fossils have been collect- in the Department of Vertebrate Paleontology at ed in other Santacrusian (South American Land the American Museum of Natural History, repre- Mammal Age, SALMA) localities from both the sented the AMNH as a member of the third Pa- coastal and northwestern areas (Bertelli & Chi- tagonian expedition led by John Bell Hatcher of appe, 2005) of Santa Cruz Province (fi gure 1). Princeton. As told by Simpson (1984: 118-121), Additional records of this Neotropical family are this was not a happy partnership and eventu- abundant in the Pliocene and Pleistocene depos- ally Brown was left behind in Patagonia. -

Northwest Argentina & Iguazu Extension

Tropical Birding Tours Trip Report NW ARGENTINA & IGUAZU Extension: November 2017 A Tropical Birding SET DEPARTURE tour NORTHWEST ARGENTINA & IGUAZU EXTENSION 1-15 November 2017 TOUR LEADER: ANDRES VASQUEZ Photos by Andres Vasquez A collage of some of the most memorable moments. From the left (going clockwise): Red-tailed Comet, the exquisite Andes at Pumamarca (part of the Humahuaca Valley), a family of the very local Citron-headed Yellow-Finch, and a view from the lower loop at Iguazu Falls during the extension. www.tropicalbirding.com +1-409-515-9110 [email protected] p.1 Tropical Birding Tours Trip Report NW ARGENTINA & IGUAZU Extension: November 2017 INTRODUCTION: Northwest Argentina is, in my opinion (and according to all my clients on this tour and past tours), one of the most UNDERESTIMATED, UNDERVALUED tours Tropical Birding offers. In reality, it is one on my all-time favorite tours to guide and one of my all-time favorite places to visit. This is thanks, not only to incredible birds we find, but also thanks to the overwhelming combination of mesmerizing landscapes throughout the tour (which includes 2 UNESCO World Heritage Natural Sites – Iguazu Falls and Humahuaca Valley), some of the best wines in the World drank by night, and a variety of habitats we bird within, from close to sea level to almost 15000ft, and from humid Yungas to high Andes desert, upper Chaco and highland Monte. Andean Hillstars love perching on rocks close to ground near Abra Lizoite at over 14500ft./4420m In terms of birds, we recorded 369 species -

The Avian Cecum: a Review

Wilson Bull., 107(l), 1995, pp. 93-121 THE AVIAN CECUM: A REVIEW MARY H. CLENCH AND JOHN R. MATHIAS ’ ABSTRACT.-The ceca, intestinal outpocketings of the gut, are described, classified by types, and their occurrence surveyed across the Order Aves. Correlation between cecal size and systematic position is weak except among closely related species. With many exceptions, herbivores and omnivores tend to have large ceca, insectivores and carnivores are variable, and piscivores and graminivores have small ceca. Although important progress has been made in recent years, especially through the use of wild birds under natural (or quasi-natural) conditions rather than studying domestic species in captivity, much remains to be learned about cecal functioning. Research on periodic changes in galliform and anseriform cecal size in response to dietary alterations is discussed. Studies demonstrating cellulose digestion and fermentation in ceca, and their utilization and absorption of water, nitrogenous com- pounds, and other nutrients are reviewed. We also note disease-causing organisms that may be found in ceca. The avian cecum is a multi-purpose organ, with the potential to act in many different ways-and depending on the species involved, its cecal morphology, and ecological conditions, cecal functioning can be efficient and vitally important to a birds’ physiology, especially during periods of stress. Received 14 Feb. 1994, accepted 2 June 1994. The digestive tract of most birds contains a pair of outpocketings that project from the proximal colon at its junction with the small intestine (Fig. 1). These ceca are usually fingerlike in shape, looking much like simple lateral extensions of the intestine, but some are complex in struc- ture.