Urban Patterns in the Punjab Region Since Protohistoric Times

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Askari Bank Limited List of Shareholders (W/Out Cnic) As of December 31, 2017

ASKARI BANK LIMITED LIST OF SHAREHOLDERS (W/OUT CNIC) AS OF DECEMBER 31, 2017 S. NO. FOLIO NO. NAME OF SHAREHOLDERS ADDRESSES OF THE SHAREHOLDERS NO. OF SHARES 1 9 MR. MOHAMMAD SAEED KHAN 65, SCHOOL ROAD, F-7/4, ISLAMABAD. 336 2 10 MR. SHAHID HAFIZ AZMI 17/1 6TH GIZRI LANE, DEFENCE HOUSING AUTHORITY, PHASE-4, KARACHI. 3280 3 15 MR. SALEEM MIAN 344/7, ROSHAN MANSION, THATHAI COMPOUND, M.A. JINNAH ROAD, KARACHI. 439 4 21 MS. HINA SHEHZAD C/O MUHAMMAD ASIF THE BUREWALA TEXTILE MILLS LTD 1ST FLOOR, DAWOOD CENTRE, M.T. KHAN ROAD, P.O. 10426, KARACHI. 470 5 42 MR. M. RAFIQUE B.R.1/27, 1ST FLOOR, JAFFRY CHOWK, KHARADHAR, KARACHI. 9382 6 49 MR. JAN MOHAMMED H.NO. M.B.6-1728/733, RASHIDABAD, BILDIA TOWN, MAHAJIR CAMP, KARACHI. 557 7 55 MR. RAFIQ UR REHMAN PSIB PRIVATE LIMITED, 17-B, PAK CHAMBERS, WEST WHARF ROAD, KARACHI. 305 8 57 MR. MUHAMMAD SHUAIB AKHUNZADA 262, SHAMI ROAD, PESHAWAR CANTT. 1919 9 64 MR. TAUHEED JAN ROOM NO.435, BLOCK-A, PAK SECRETARIAT, ISLAMABAD. 8530 10 66 MS. NAUREEN FAROOQ KHAN 90, MARGALA ROAD, F-8/2, ISLAMABAD. 5945 11 67 MR. ERSHAD AHMED JAN C/O BANK OF AMERICA, BLUE AREA, ISLAMABAD. 2878 12 68 MR. WASEEM AHMED HOUSE NO.485, STREET NO.17, CHAKLALA SCHEME-III, RAWALPINDI. 5945 13 71 MS. SHAMEEM QUAVI SIDDIQUI 112/1, 13TH STREET, PHASE-VI, DEFENCE HOUSING AUTHORITY, KARACHI-75500. 2695 14 74 MS. YAZDANI BEGUM HOUSE NO.A-75, BLOCK-13, GULSHAN-E-IQBAL, KARACHI. -

Village & Townwise Primary Census Abstract, Jullundur, Part X-A & B

,CENSUS 1971 PARTS X-A" II VILLAGE & TOWN SERIES 17 DIRECTORY PUNJAB VILLAGE & TOWN WISE PRIMARY CENS'US ABSTRACT DISTRICT JULLUN'DUR CENSUS DISTRICT HANDBOOK P. L. SONDHI H. S. KWATRA ". OF THE INDIAN ADMINISTRATIVE SERVICE OF THE PfJ'NJAB CIVIL SERVIce Ex-officio Director of Census OperatiONl Deputy Director (~l Cpnsus Operations ', .. PUNJAB PUNJAB' Modf:- Julluodur - made Sports Goods For 01 ympics ·-1976 llvckey al fhe Montreal Olympics. 1976, will be played with halls manufactured in at Jullundur. Jullundur has nearly 350 sports goods 111l1nl~ractur;l1g units of various sizes. These small units eXJlort tennis and badminton rackets, shuttlecocks and several types of balls including cricket balls. Tlte nucleu.s (~( this industry was formed h,J/ skilled and semi-skilled workers who came to 1ndia a/It?r Partition. Since they could not afford 10 go far away and were lodged in the two refugee can'lps located on the outskirts of .IuJ/undur city in an underdeveloped area, the availabi lity of the sk illed work crs attracted the sport,\' goods I1zCllllljacturers especiallY.from Sialkot which ,was the centre (~f sports hJdustry heji,)re Partition. Over 2,000 people are tU preSt'nt employed in this industry. Started /roln scratch after ,Partilion, the indLlstry now exports goods worth nearly Rs. 5 crore per year to tire Asian and European ("'omnu)fzwealth countril's, the lasl being our higgest ilnporters. Alot(( by :-- 1. S. Gin 1 PUNJAB DISTRICT JULLUNDUR kflOMlTR£S 5 0 5 12_ Ie 20 , .. ,::::::;=::::::::;::::_:::.:::~r::::_ 4SN .- .., I ... 0 ~ 8 12 MtLEI "'5 H s / I 30 3~, c ! I I I I ! JULLUNOUR I (t CITY '" I :lI:'" I ,~ VI .1 ..,[-<1 j ~l~ ~, oj .'1 i ;;1 ~ "(,. -

Geospatial Analysis of Indus River Meandering and Flow Pattern from Chachran to Guddu Barrage, Pakistan Vol 9 (2), December 2018

Geospatial Analysis of Indus River Meandering and Flow Pattern from Chachran to Guddu Barrage, Pakistan Vol 9 (2), December 2018 Open Access ORIGINAL ARTICLE Full Length Ar t icle Geospatial Analysis of Indus River Meandering and Flow Pattern from Chachran to Guddu Barrage, Pakistan Danish Raza* and Aqeel Ahmed Kidwai Department of Meteorology-COMSATS University Islamabad, Islamabad, Pakistan ABS TRACT Natural and anthropogenic influence affects directly ecologic equilibrium and hydro morphologic symmetry of riverine surroundings. The current research intends to study the hydro morphologic features (meanders, shape, and size) of Indus River, Pakistan by using remote sensing (RS) and geographical information science (GIS) techniques to calculate the temporal changes. Landsat satellite imagery was used for qualitative and analytical study. Satellite imagery was acquired from Landsat Thematic Mapper (TM), Enhanced Thematic Mapper Plus (ETM+) and Operational Land Imager (OLI). Temporal satellite imagery of study area was used to identify the variations of river morphology for the years 1988,1995,2002,2009 and 2017. Research was based upon the spatial and temporal change of river pattern with respect to meandering and flow pattern observations for 30 years’ temporal data with almost 7 years’ interval. Image preprocessing was applied on the imagery of the study area for the better visualization and identification of variations among the objects. Object-based image analysis technique was performed for better results of a feature on the earth surface. Model builder (Arc GIS) was used for calculation of temporal variation of the river. In observation many natural factor involves for pattern changes such as; floods and rain fall. -

Repair Programme 2018-19 Administr Ative Detail of Repair Approval Name of Name Xen/Mobile No

Repair Programme 2018-19 Administr ative Detail of Repair Approval Name of Name Xen/Mobile No. Sr. No. Distt. MC Name of Work Strengthe Premix Contractor/Agency Name of SDO/Mobile No. Length Cost Raising ning Carepet in in Km. in lacs in Km in Km Km 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 PARTAPPURA TO DERA SEN BHAGAT M/S Kiscon Xen. Gurinder Singh Cheema/ 988752700 1 Jalandhar Bilga 2.4 15.06 0 0 2.4 (16 ft wide) (1.50 km length) Construction Sdo Gurmeet Singh/ 9988452700 MAO SAHIB TO DHUSI BANDH (KHERA M/S Kiscon Xen. Gurinder Singh Cheema/ 988752700 2 Jalandhar Bilga 4.24 40.31 0 2.44 4.24 BET)VIA KULIAN TEHAL SINGH Construction Sdo Gurmeet Singh/ 9988452700 MAU SAHIB TO RURKA KALAN VIA M/S Kiscon Xen. Gurinder Singh Cheema/ 988752700 3 Jalandhar Bilga PARTABPURA MEHSAMPUR (13.15= 21.04 128.57 0.31 0.82 21.04 Construction Sdo Gurmeet Singh/ 9988452700 16' wide) PHIRNI PIND MAOSAHIB TO MAOSAHIB M/S Kiscon Xen. Gurinder Singh Cheema/ 988752700 4 Jalandhar Bilga 0.8 7.75 0 0.435 0.8 DHUSI BAND ROAD Construction Sdo Gurmeet Singh/ 9988452700 PHILLAUR RURKA KALAN TO RURKA Sh. Rakesh Kumar Xen. Gurinder Singh Cheema/ 988752700 5 Jalandhar Bilga 3.35 31.06 0 1.805 3.35 KALAN MAU SAHIB ROAD Contractor Sdo Gurmeet Singh/ 9988452700 PHILLAUR NURMAHAL ROAD TO Sh. Rakesh Kumar Xen. Gurinder Singh Cheema/ 988752700 6 Jalandhar Bilga 3.1 24.27 0 1.015 3.1 PRATABPURA VIA SANGATPUR Contractor Sdo Gurmeet Singh/ 9988452700 Sh. -

Agromet Advisory Bulletin for the State of Haryana Bulletin No

Agromet Advisory Bulletin for the State of Haryana Bulletin No. 77/2021 Issued on 24.09.2021 Part A: Realized and forecast weather Summary of past weather over the State during (21.09.2021 to 23.09.2021) Light to Moderate Rainfall occured at many places with Moderate to Heavy rainfall occurred at isolated places on 21th and at most places on 22th & 23th in the state. Mean Maximum Temperatures varied between 30-32oC in Eastern Haryana which were 01-02oC below normal and in Western Haryana between 33-35 oC which were 01-02 oC below normal. Mean Minimum Temperatures varied between 24-26 oC Eastern Haryana which were 02-03oC above normal and in Western Haryana between 24-26 oC which were 00-01 oC above normal. Chief amounts of rainfall (in cms):- 21.09.2021- Gohana (dist Sonepat) 9, Khanpur Rev (dist Sonepat) 7, Panipat (dist Panipat) 7, Kalka (dist Panchkula) 5, Dadri (dist Charkhi Dadri) 5, Panchkula (dist Panchkula) 5, Ganaur (dist Sonepat) 4, Israna (dist Panipat) 4, Fatehabad (dist Fatehabad) 4, Madluda Rev (dist Panipat) 4, Panchkula Aws (dist Panchkula) 3, Sonepat (dist Sonepat) 3, Naraingarh (dist Ambala) 3, Beri (dist Jhajjar) 2, Sirsa Aws (dist Sirsa) 2, Kharkoda (dist Sonepat) 2, Jhahhar (dist Jhajjar) 2, Uklana Rly (dist Hisar) 2, Uklana Rev (dist Hisar) 2, Raipur Rani (dist Panchkula) 2, Jhirka (dist Nuh) 2, Hodal (dist Palwal) 2, Rai Rev (dist Sonepat) 2, Morni (dist Panchkula) 2, Sirsa (dist Sirsa) 1, Hassanpur (dist Palwal) 1, Partapnagar Rev (dist Yamuna Nagar) 1, Bahadurgarh (dist Jhajjar) 1, Jagdishpur Aws (dist Sonepat) -

SAHIWAL-REN362.Pdf

Renewal List S/NO REN# / NAME FATHER'S NAME PRESENT ADDRESS DATE OF ACADEMIC REN DATE BIRTH QUALIFICATION 1 14261 ZAHID MAHMUD TAJUDDIN KHALID BARTAN STORE PAKPATTAN BAZAR , 15/4/1964 MATRIC 30/02/2017 SAHIWAL, PUNJAB 2 394676 MANSAB ALI SARANG ALI 94 - 19/C P/O 93/9-L DISTT. SAHIWAL , SAHIWAL, 10-2-1959 MATRIC 10/7/2014 PUNJAB 3 27290 SHAHIDA MUHAMMAD H. NO. 541, KAKAR MANDI SAHIWAL SAHIWAL , 2-5-1971 MATRIC 10/07/2014 HUSSAIN SAHIWAL, PUNJAB 4 31388 KHALID MAHMUD KHUSHI FLAT NO. 01, OFFICER COLONY NEAR COLLEGE 8-5-1954 BA 10/07/2014 MUHAMMAD CHAK FAREED TOWN ROAD , SAHIWAL, PUNJAB 5 48207 ISMAT RAUF ABDUL RAUF H/NO. 309-W SCHEME NO. 3 FARID TOWN 23-5-1969 MSC 11/07/2014 SAHIWAL , SAHIWAL, PUNJAB 6 30278 MUHAMMAD NASEER AHMAD MEHERABAD TOWN ST#1, SAHIWAL, PUNJAB 1-1-1986 MATRIC 11/07/2014 ANWAR-UL-HAQ 7 21269 KAFIL AHMED MUSHTAQ AHMED 7-11-L RANWAN WALA P/O KHAS, TEHCHICHA 1/12/1976 MATRIC 13/07/2014 WATNI DISTT, SAHIWAL, PUNJAB 8 22039 LIAQAT ALI SHAH MUHAMMAD CHAK 105 /9-CP.O. SAME, SAHIWAL, PUNJAB 1/1/1966 MATRIC 14/07/2014 9 40880 MUHAMMAD MUHAMMAD CHAK NO. 55/4-R P/O TEH & DISTT. , SAHIWAL, 20-5-1963 MATRIC 15/7/2014 SADIQ YAQOOB PUNJAB 10 46545 GHULAM QADIR MUHAMMAD MOH, PHILI CAT P/O OKARA CANTTCHAK NO. 26-1-1974 MATRIC 15/07/2014 ABBAS 56/4-R TEH, & DISTT. SAHIWAL , SAHIWAL, PUNJAB 11 25355 MEHMOOD MUHAMMAD ST.NO.5 SHAMAS PURACHICHAWATNI, SAHIWAL, 17/1/1973 MATRIC 03/08/2014 AHMED ASGHAR PUNJAB 12 25357 MAHBOOB ALI MUHAMMAD DIN MOH AHMAD NAGAR ST.NO.3 H.NO231CHICHA 6/4/1980 MATRIC 03/08/2014 WATNI, SAHIWAL, PUNJAB 13 30330 MUHAMMAD BASHIR AHMED CHAK NO. -

Sargodha District Sargodha

DISTRICT DISASTER MANAGEMENT PLAN 2020 DIVISION SARGODHA DISTRICT SARGODHA IDP Camp in 2009 Earthquake Flood Mock Exercise in May 2020 Corona virus Pandemic-Training to wear PPE’s Prepared by: MAZHAR SHAH, DISTRICT EMERGENCY OFFICER Approved by: DDMA Sargodha DDMP 2020 TABLE OF CONTENTS Executive Summary .................................................................................................................................................... 1 Aim and Objectives ..................................................................................................................................................... 2 District Profile .............................................................................................................................................................. 3 Coordination Mechanism ............................................................................................................................................ 9 Risk Analysis............................................................................................................................................................ 19 Mitigation Strategy ................................................................................................................................................... 25 Early Warning .......................................................................................................................................................... 28 Rescue Strategy ..................................................................................................................................................... -

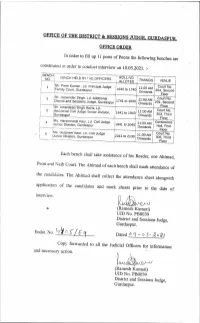

Roll Number.Pdf

POST APPLIED FOR :- PEON Roll No. Application No. Name Father’s Name/ Husband’s Name Permanent Address 1 284 Aakash Subash Chander Hno 241/2 Mohalla Nangal Kotli Mandi Gurdaspur 2 792 Aakash Gill Tarsem lal Village Abulkhair Jail Road, Gurdaspur 3 1171 Aakash Masih Joginder Masih Village Chuggewal 4 1014 Aakashdeep Wazir Masih Village Tariza Nagar, PO Dhariwal, Gurdaspur 5 2703 Abhay Saini Parvesh Saini house no DF/350,4 Marla Quarter Ram Nagar Pathankot 6 1739 Abhi Bhavnesh Kumar Ward No. 3, Hno. 282, Kothe Bhim Sen, Dinanagar 7 1307 Abhi Nandan Niranjan Singh VPO Bhavnour, tehsil Mukerian , District Hoshiarpur 8 1722 Abhinandan Mahajan Bhavnesh Mahajan Ward No. 3, Hno. 282, Kothe Bhim Sen, Dinanagar 9 305 Abhishek Danial Hno 145, ward No. 12, Line No. 18A Mill QTR Dhariwal, District Gurdaspur 10 465 Abhishek Rakesh Kumar Hno 1479, Gali No 7, Jagdambe Colony, Majitha Road , Amritsar 11 1441 Abhishek Buta Masih Village Triza Nagar, PO Dhariwal, Gurdaspur 12 2195 Abhishek Vijay Kumar Village Meghian, PO Purana Shalla, Gurdaspur 13 2628 Abhishek Kuldeep Ram VPO Rurkee Tehsil Phillaur District Jalandhar 14 2756 Abhishek Shiv Kumar H.No.29B, Nehru Nagar, Dhaki road, Ward No.26 Pathankot-145001 15 1387 Abhishek Chand Ramesh Chand VPO Sarwali, Tehsil Batala, District Gurdaspur 16 983 Abhishek Dadwal Avresh Singh Village Manwal, PO Tehsil and District Pathankot Page 1 POST APPLIED FOR :- PEON Roll No. Application No. Name Father’s Name/ Husband’s Name Permanent Address 17 603 Abhishek Gautam Kewal Singh VPO Naurangpur, Tehsil Mukerian District Hoshiar pur 18 1805 Abhishek Kumar Ashwani Kumar VPO Kalichpur, Gurdaspur 19 2160 Abhishek Kumar Ravi Kumar VPO Bhatoya, Tehsil and District Gurdaspur 20 1363 Abhishek Rana Satpal Rana Village Kondi, Pauri Garhwal, Uttra Khand. -

Legal Control on Groundwater Resources

LEGAL CONTROL ON GROUNDWATER RESOURCES ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS SUBMITTED FOR THE AWARD OF THE DEGREE OF Boctor of ^Ijiloslopljp A IN BY HARIS UMAR Under the Supervision of PROF. (DR.) IQBAL ALI KHAN (Dean & Chairman) DEPARTMENT OF LAW ALIGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY ALIGARH (INDIA) 2008 ABSTRACT Preservation of water has been the essence of Vedic culture. However, there was a change in the attitude and belief of our people through modernization. Rapid industrialization and urbanization infused material culture and in this process of development, the natural resources like ground water had lost its importance. Industrial and agriculture boom has resulted in ground water depletion and pollution. Its easy access has always attracted human activities, but its complexity in understanding has led to misuse and abuse. According to State Ground Water Board officials, water tables are dropping by six meter or more each year. It was learnt that farmers in the country, a generation ago used bullocks to lift water from shallow wells in leather buckets. But now they are drawing water from SOOmetres below ground using electric pumps. The pumps powered by heavy subsidy are working day and night to irrigate fields of more water consuming crops like rice, banana and sugarcane. The law allows landowners practically unrestricted right of extraction of groundwater from under their plots. This vital question needs to be addressed properly so as to develop a correct and cognizable perception about legal framework of rights in the domain of water regulation. The problem of water pollution is as old as the evolution of human being on this planet. -

Administrative Atlas , Punjab

CENSUS OF INDIA 2001 PUNJAB ADMINISTRATIVE ATLAS f~.·~'\"'~ " ~ ..... ~ ~ - +, ~... 1/, 0\ \ ~ PE OPLE ORIENTED DIRECTORATE OF CENSUS OPERATIONS, PUNJAB , The maps included in this publication are based upon SUNey of India map with the permission of the SUNeyor General of India. The territorial waters of India extend into the sea to a distance of twelve nautical miles measured from the appropriate base line. The interstate boundaries between Arunachal Pradesh, Assam and Meghalaya shown in this publication are as interpreted from the North-Eastern Areas (Reorganisation) Act, 1971 but have yet to be verified. The state boundaries between Uttaranchal & Uttar Pradesh, Bihar & Jharkhand and Chhattisgarh & Madhya Pradesh have not been verified by government concerned. © Government of India, Copyright 2006. Data Product Number 03-010-2001 - Cen-Atlas (ii) FOREWORD "Few people realize, much less appreciate, that apart from Survey of India and Geological Survey, the Census of India has been perhaps the largest single producer of maps of the Indian sub-continent" - this is an observation made by Dr. Ashok Mitra, an illustrious Census Commissioner of India in 1961. The statement sums up the contribution of Census Organisation which has been working in the field of mapping in the country. The Census Commissionarate of India has been working in the field of cartography and mapping since 1872. A major shift was witnessed during Census 1961 when the office had got a permanent footing. For the first time, the census maps were published in the form of 'Census Atlases' in the decade 1961-71. Alongwith the national volume, atlases of states and union territories were also published. -

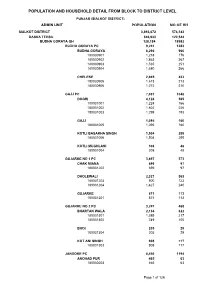

Sialkot Blockwise

POPULATION AND HOUSEHOLD DETAIL FROM BLOCK TO DISTRICT LEVEL PUNJAB (SIALKOT DISTRICT) ADMIN UNIT POPULATION NO OF HH SIALKOT DISTRICT 3,893,672 574,143 DASKA TEHSIL 846,933 122,544 BUDHA GORAYA QH 128,184 18982 BUDHA GORAYA PC 9,241 1383 BUDHA GORAYA 6,296 960 180030901 1,218 176 180030902 1,863 267 180030903 1,535 251 180030904 1,680 266 CHELEKE 2,945 423 180030905 1,673 213 180030906 1,272 210 GAJJ PC 7,031 1048 DOGRI 4,124 585 180031001 1,224 166 180031002 1,602 226 180031003 1,298 193 GAJJ 1,095 160 180031005 1,095 160 KOTLI BASAKHA SINGH 1,504 255 180031006 1,504 255 KOTLI MUGHLANI 308 48 180031004 308 48 GUJARKE NO 1 PC 3,897 573 CHAK MIANA 699 97 180031202 699 97 DHOLEWALI 2,327 363 180031203 900 123 180031204 1,427 240 GUJARKE 871 113 180031201 871 113 GUJARKE NO 2 PC 3,247 468 BHARTAN WALA 2,134 322 180031301 1,385 217 180031302 749 105 BHOI 205 29 180031304 205 29 KOT ANI SINGH 908 117 180031303 908 117 JANDOKE PC 8,450 1194 ANOHAD PUR 465 63 180030203 465 63 Page 1 of 126 POPULATION AND HOUSEHOLD DETAIL FROM BLOCK TO DISTRICT LEVEL PUNJAB (SIALKOT DISTRICT) ADMIN UNIT POPULATION NO OF HH JANDO KE 2,781 420 180030206 1,565 247 180030207 1,216 173 KOTLI DASO SINGH 918 127 180030204 918 127 MAHLE KE 1,922 229 180030205 1,922 229 SAKHO KE 2,364 355 180030201 1,250 184 180030202 1,114 171 KANWANLIT PC 16,644 2544 DHEDO WALI 6,974 1092 180030305 2,161 296 180030306 1,302 220 180030307 1,717 264 180030308 1,794 312 KANWAN LIT 5,856 854 180030301 2,011 290 180030302 1,128 156 180030303 1,393 207 180030304 1,324 201 KOTLI CHAMB WALI -

Tender Notice

TENDER NOTICE Sealed tenders based on percentage rates, items rates are hereby invited from the approved contractor registered in any local council of Sargodha Division for the year 2020- 21 on MRS JANUARY 2021 JUNE 2021 of Finance Department. Tender rates and amounts should be filled in figure as well as in words and tender should be signed as per general directions given in the tender documents. Conditional tenders will not be entertained. Applications along with earnest money @ 5% of estimated cost in shape of CDR of any scheduled bank to issuance of Tender Form must be received at office of the Assistant Tehsil Officer (I&S) from the date of publication of this advertisement up to 21/06/2021 in office hours. The sealed tender documents must be deposited up to 23/06/2021 at 01:00 (PM) and will be opened at 02:00 (PM) on same day by the Tender Opening Committee in the presence of contractors or their authorized agents. No telegraphic or by post tender will be entertained. A performance guarantee 10% of tender cost (Balance amount adjusting 5% of earnest money) should be deposited within 15 days by the contractor whose rates are approved by Competent Authority as per Works Rules 2017. If he does not deposit the required amount then his 5% CDR deposited will be forfeited and tender will be rejected. “Tender documents can be obtained from office of Assistant Tehsil Officer (I&S) after depositing of Rs.1,000/- per tender through Bank Challan in Account No. 6620200397500017 Bank of Punjab, Bhera.