“THE STATUS IS NOT QUO” Gender and Performance in Dr

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Collection of Texts Celebrating Joss Whedon and His Works Krista Silva University of Puget Sound, [email protected]

Student Research and Creative Works Book Collecting Contest Essays University of Puget Sound Year 2015 The Wonderful World of Whedon: A Collection of Texts Celebrating Joss Whedon and His Works Krista Silva University of Puget Sound, [email protected] This paper is posted at Sound Ideas. http://soundideas.pugetsound.edu/book collecting essays/6 Krista Silva The Wonderful World of Whedon: A Collection of Texts Celebrating Joss Whedon and His Works I am an inhabitant of the Whedonverse. When I say this, I don’t just mean that I am a fan of Joss Whedon. I am sincere. I live and breathe his works, the ever-expanding universe— sometimes funny, sometimes scary, and often heartbreaking—that he has created. A multi- talented writer, director and creator, Joss is responsible for television series such as Buffy the Vampire Slayer , Firefly , Angel , and Dollhouse . In 2012 he collaborated with Drew Goddard, writer for Buffy and Angel , to bring us the satirical horror film The Cabin in the Woods . Most recently he has been integrated into the Marvel cinematic universe as the director of The Avengers franchise, as well as earning a creative credit for Agents of S.H.I.E.L.D. My love for Joss Whedon began in 1998. I was only eleven years old, and through an incredible moment of happenstance, and a bit of boredom, I turned the television channel to the WB and encountered my first episode of Buffy the Vampire Slayer . I was instantly smitten with Buffy Summers. She defied the rules and regulations of my conservative southern upbringing. -

ENTERTAINMENT WEEKLY (ISSN 10490434) IS PUBLISHED WEEKLY EXCEPT Results

SPECIAL TRIBUTE ISSUE GEORGE MICHAEL 1963–2016 JAN. 13, 2017 • #1448 Plus THE WINTER PEOPLE’S PRINCESS TV PREVIEW CARRIE P. 34 FISHER 1956–2016 THE AMAZING LIFE OF A STAR WARS ICON REMEMBERING HER LEGENDARY MOM, DEBBIE REYNOLDS 1932–2016 STARRING EXECUTIVE PRODUCER EXECUTIVE PRODUCER GIOVANNI RIBISI GRAHAM YOST BRYAN CRANSTON STREAMJAN THE TOP 10 THINGS WE LOVE THIS WEEK Nick Viall 2 3 4 THE BACHELOR THE : MITCH HAASETH/ABC; ILLUSTRATION BACKGROUND: CRAIG SJODIN/ABC 1 5 1 2 3 4 5 ; PATERSON TV MOVIES BOOKS PODCASTS TV THE BACHELOR PATERSON THE SPY WHO TWICE REMOVED PORTLANDIA : MARY CYBULSKY; • Former Bachelor in • Jim Jarmusch’s sweet COULDN’T SPELL, • Host A.J. Jacobs seeks • Fred starts his own Paradise and two-time indie celebrates the by Yudhijit to prove we are family phone company, Carrie Bachelorette contestant mundanities of everyday Bhattacharjee by tracing the ancestry dates a hunk, and Nick Viall is back for more existence, following • In this remarkable true of a notable guest each Candace and Toni PORTLANDIA roses, champagne, and a New Jersey bus driver story about the hunt week. As he discovers explore life as feminist- tears. In the 21st season, and amateur poet for a brilliant American ties to historical figures bookstore retirees. the 36-year-old romantic (Star Wars’ Adam Driver) traitor who claimed to be and the common man, The seventh season of QUIRK/IFC AUGUSTA : will date 30 women in through seven days in a CIA analyst, the FBI Jacobs mixes humor, Fred Armisen and the hopes of finding true his life—from the 6 a.m. -

Zack Whedon Davidé Fabbri Zack Whedon 2/17/12 1:11 Pm ® S R

ZACKZACK WHEDONWHEDON ® DAVIDÉDAVIDÉ FABBRIFABBRI STAR WARS FREE ® FROM YOUR PALS AT DARK HORSE COMICS AND COMICS HORSE DARK AT PALS YOUR FROM FCBD12 SW-SEREN.indd 1 2/17/12 1:11 PM FCBD12 SW-SEREN.indd 2 tions, or locales, without satiric intent, is coincidental. Printed by Cadmus Communications, Easton, PA, U.S.A. tions, orlocales,without satiricintent,iscoincidental.Printed byCadmusCommunications,Easton, PA, Anyresemblancetoactual persons(livingordead),events,institu either aretheproduct oftheauthor’simaginationorareused fictitiously. writtenpermissionofDarkHorse Comics,Inc.Names,characters,places,andincidentsfeaturedinthispublication without theexpress categories andcountries.Allrightsreserved. Noportionofthispublicationmaybereproducedortransmitted,inanyform or are ©2012LucasfilmLtd.DarkHorse Comics® andtheDarkHorselogoaretrademarksofComics,Inc.,registered inva Wars andillustrationsforStar Text ©2012LucasfilmLtd.&™.Allrightsreserved.Usedunderauthorization. Milwaukie, OR97222.StarWars ArtoftheBadDeal,”May2012.PublishedbyDarkHorseComics, Inc.,10956SEMainStreet, WARS—“The STAR FREE COMICBOOK DAY: RONDA D MICHAEL A D ZACK WHEDON ZACK advertising sales: (503) 905-2370 » comic shop locator service: (888)266-4226 service: (503)905-2370»comicshop locator sales: advertising ALLA ALLA DA AVIDÉ FABBRI AVIDÉ MIKE RANDY RANDY M H M C assistant editor assistant collection editor P F HRISTIAN REDD cover art SIERRA R lettering V T ATTISON T ICHARDSON INA ALESSI ECCHIA talk about this issue online at: online at: aboutthisissue talk Pencils HO UGHES Colors STRADLE publisher D script designer YE YE AVID M editor Inks HAHN LINS AS Y STAR WARS | STAR WARS | STAR WARS | STAR WARS | STAR WARS | STAR WARS | STAR WARS | STAR WARS | STAR WARS | STAR WARS | STAR WARS | STAR WARS ANDERMAN at lucas licensing. ANDERMAN at ALDERS, CAROL special thankstoJ ROEDER Comics! Horse Dark from pals this your at free offering enjoy please afirst-timer, or time reader along you’re whether But Emperor. -

Firefly: Legacy Edition Book Two Kindle

FIREFLY: LEGACY EDITION BOOK TWO PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Zack Whedon | 336 pages | 21 Mar 2019 | Boom! Studios | 9781684153084 | English | Los Angeles, United States Firefly: Legacy Edition Book Two PDF Book Animal Farm and by George Orwell and A. Prices and offers may vary in store. About the Author Joss Whedon is an American producer, director, screenwriter, comic book writer, and composer. To see if pickup is available, select a store. Screnwriting runs in Zachary Whedon's family. Chesapeake Bay Ckbk. See all 19 - All listings for this product. Peter Grant is facing fatherhood, and an uncertain future, with equal amounts of panic and enthusiasm. Firefly 21 [26]. Shelve 8-Bit Christmas. Author : Alex G. Horrible's Sing-Along Blog. Views Read Edit View history. See details. The official follow-up to the critically acclaimed hit film Serenity, that sees the band of Firefly 23 [28]. Fragrance of the Lord. Unleashing the Wild Physique Graham , Winston. Shelve The Magnificent Nine Firefly 2. Firefly 2 by Greg Pak. Firefly: Legacy Edition Book Two Writer Angel h Firefly 15 [19]. From the heart of the Whedonverse comes the next chapter of Firefly! Firefly 22 [27]. This Barnes and Noble exclusive edition features both a variant cover by JOCK and a bonus page story from critically acclaimed screenwriter Josh Lee Gordon and artist Francesco Mortarino, revealing the secret origin of one of the most beloved Firefly One of Serenity 's greatest mysteries is finally revealed in The Shepherd's Tale , filling in the life of one of the show's most beloved characters—Shepherd Book! More books from this author: Zack Whedon. -

2009 Annual Report

2009 ANNUAL REPORT Table of Contents Letter from the President & CEO ......................................................................................................................5 About The Paley Center for Media ................................................................................................................... 7 Board Lists Board of Trustees ........................................................................................................................................8 Los Angeles Board of Governors ................................................................................................................ 10 Media Council Board of Governors ..............................................................................................................12 Public Programs PALEYDOCEVENTS ..................................................................................................................................14 INSIDEMEDIA Events .................................................................................................................................15 PALEYDOCFEST .......................................................................................................................................19 PALEYFEST: Fall TV Preview Parties ..........................................................................................................20 PALEYFEST: William S. Paley Television Festival ..........................................................................................21 Robert M. -

Los Angeles, CA: East West Announces Honorees for 48Th

For Immediate Release Contact: Kat Carrido March 17, 2014 (213) 625-7000 ext. 12 Los Angeles, CA [email protected] East West Players’ 48th Anniversary Visionary Awards Dinner & Silent Auction on April 28th Honors Reggie Lee (Grimm), Maurissa Tancharoen (Agents of S.H.I.E.L.D.), Peter Lenkov and Ken Solarz (Hawaii 5-0), and Playwright Paul Kikuchi East West Players (EWP), the nation’s premier Asian American theatre, celebrates the achievements of individuals who have raised the visibility of the Asian Pacific American (APA) community through their craft at the 48th Anniversary Visionary Awards Dinner & Silent Auction. The fundraising event will take place on Monday April 28, 2014 at the Universal Hilton. Proceeds from the gala will benefit East West Players’ educational and artistic programs. "Opportunities for Asian American artists and executives in the entertainment industry are beginning to increase each year with greater momentum," said Tim Dang, Producing Artistic Director of East West Players. "With America's changing demographics and a larger global reach, the entertainment industry must recognize the wealth of Asian American talent and the rich and cultural diversity that emanate from our community. While there is still much work to be done to increase our visibility, we thank our long standing partners at The Walt Disney Company, CBS and NBC and welcome new partners such as Mattel, HBO and Mnet America. We salute those who have made a valuable impact on the APA community and congratulate all of our honorees." “I am humbled receiving an award with the word ‘visionary’in it,” says honoree, actor Reggie Lee. -

The Expanded 'Verse

The Expanded 'Verse: Serialized Transmediality in Firefly/Serenity ............ by Frederick Blichert, BA (Hons.) A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Affairs in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Film Studies Carleton University OTTAWA, Ontario Submitted August 2014 © 2014, Frederick Blichert ii We know now that a text is not a line of words releasing a single "theological" meaning (the "message" of the Author- God) but a multi-dimensional space in which a variety of writings, none of them original, blend and clash. Roland Barthes1 iii ABSTRACT Popular narratives often extend textual content across multiple media platforms, creating transmedia stories. Recent scholarship has stressed the permeability of "the text," suggesting that the framework of a text, made up of paratexts including trailers and DVD extras, must be included in textual analysis. Here, I propose that this notion may be productively coupled with a theory of seriality––we may frame this phenomenon in the filmic terms of a narrative being comprised of transmedia sequels and/or prequels, or in the televisual language of episodes in a series. Through a textual analysis of the multifaceted transmedia narrative Firefly (2002-2003), I argue for a theoretical framework that further destabilizes the traditional text by considering such paratextual works as comic books, web videos, and the feature film Serenity (Joss Whedon, 2005) as narrative continuations within a single metatext that eschews the centrality of any one text over the others in favour of seriality. iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I wish to thank Erika Balsom, Malini Guha, André Loiselle, and Charles O'Brien for their notes on various versions, drafts, and proposals of this material, along with Sylvie Jasen and Murray Leeder, who encouraged me to workshop some of these ideas as guest lecturer in their undergraduate courses. -

Zombies, Reavers, Butchers, and Actuals in Joss Whedon's Work Gerry Canavan Marquette University, [email protected]

Marquette University e-Publications@Marquette English Faculty Research and Publications English, Department of 1-1-2012 Zombies, Reavers, Butchers, and Actuals in Joss Whedon's Work Gerry Canavan Marquette University, [email protected] Published version. "Zombies, Reavers, Butchers, and Actuals in Joss Whedon's Work," in Joss Whedon: The Complete Companion: The TV Series, The Movies, The Comic Books and More. Ed. PopMatters Media. London: Titan Books, 2012: 285-297. Publisher Link. © 2012 Titan Books. Used with permission. FIREFLY 3.10 3.10 Zombies, Reavers, Butchers, and Actuals in Joss Whedon's Work Gerry Canavan For all the standard horror movie monsters Joss Whedon took up in Buffy and Angel-vampires, of course, but also ghosts, demons, werewolves, witches, Frankenstein's monster, the Devil, mummies, haunted puppets, the Creature from the Black Lagoon, the "bad boyfriend," and so on-you'd think there would have been more zombies. In twelve years of television across both series zombies appear in only a handful of episodes. They attack almost as an afterthought at Buffy's drama-laden homecoming party early in Buffy Season 3 ("Dead Man's Party" 3.2); they completely ruin Xander's evening in "The Zeppo" (3.13) later that same season; they patrol Angel's Los Angeles neighborhood in "The Thin Dead Line" (2.14) in Angel Season 2; they stalk the halls of Wolfram & Hart in "Habeas Corpses" (4.8) in Angel Season 4. A single zombie comes back from the dead to work things out with the girlfriend who poisoned him in a subplot in "Provider" (3.12) in Angel Season 3; Adam uses science to reanimate dead bodies to make his lab assistants near the end of Buffy Season 4 ("Primeval" 4.21); zombies guard a fail-safe device in the basement of Wolfram & Hart in "You're Welcome" (3.12) in Angel Season 5. -

1 Joss Whedon, Dr. Horrible and the Future of Web Media? 24

JOSS WHEDON, DR. HORRIBLE AND THE FUTURE OF WEB MEDIA? 1 Joss Whedon, Dr. Horrible and the Future of Web Media? Tama Leaver Department of Internet Studies, Curtin University Tel +61 8 9266 1258 Fax +61 8 9266 3166 [email protected] Correspondence should be addressed to Tama Leaver, Curtin University, GPO Box U1987, Perth WA 6845, AUSTRALIA. Email: [email protected] JOSS WHEDON, DR. HORRIBLE AND THE FUTURE OF WEB MEDIA? 2 Abstract In the 2007 Writers Guild of America strike, one of the areas in dispute was the question of residual payments for online material. On the picket line, Buffy creator Joss Whedon discussed new ways online media production could be financed. After the strike, Whedon self-funded a web media production, Dr. Horrible’s Sing-along Blog. Whedon and his collaborators positioned Dr. Horrible as an experiment, investigating whether original online media content created outside of studio funding could be financially viable. Dr. Horrible was a bigger hit than expected, with a paid version topping the iTunes charts and a DVD release hitting the number two position on Amazon. This article explores which factors most obviously contributed to Dr. Horrible’s success, whether these factors are replicable by other media creators, the incorporation of fan labor into web media projects, and how web-specific content creation relates to more traditional forms of media production. Keywords: Web Media, Online Distribution, Joss Whedon, Dr. Horrible, Paratexts, Social Media, Labor, Fans JOSS WHEDON, DR. HORRIBLE AND THE FUTURE OF WEB MEDIA? 3 Joss Whedon, Dr. Horrible and the Future of Web Media? In November 2007, the Writers Guild of America (WGA) began a strike lasting 100 days; amongst the areas in dispute were questions of residual payments for online streaming of previously broadcast material and the even newer and murkier territory of content created specifically for viewing online (M. -

Authorship and Authenticity in the Transmedia Brand: the Case of Marvel's Agents of S.H.I.E.L.D

Authorship and Authenticity in the Transmedia Brand: The Case of Marvel's Agents of S.H.I.E.L.D. LEORA HADAS, University of Nottingham ABSTRACT The Marvel Cinematic Universe (MCU) is the first filmmaking endeavour of its kind: multiple separate superhero films taking place within a single diegetic world, united in a single sequel, The Avengers (2012). The third highest-grossing film in history, The Avengers drew not only on the success of its prequels, its established characters and its stars, but perhaps most of all on its writer- director, cult favourite television auteur Joss Whedon. Having delivered on the film, and with considerable experience in creating quirky, character-based telefantasy, Whedon was a natural choice for Marvel for creating the MCU's first expansion into television, ABC’s Marvel's Agents of S.H.I.E.LD (ABC Studios/Marvel Television/Mutant Enemy, 2013- ). This article examines the use of Whedon's name and his presence in the promotional discourse of Agents of S.H.I.E.LD as a case study of the role of the media creator in extending the transmedia brand. With the names of creators becoming increasingly visible in association with many texts where they were previously absent, such as television series and blockbuster Hollywood cinema, the use of the author name as a brand name sees growing prevalence across the screen industries. In theorizing transmedia storytelling, Elizabeth Evans (2010) has, accordingly, named authorship as one of the key dimensions in which cohesion is established. In this context, I examine the use of Whedon's involvement in the Marvel Cinematic Universe, where the discourse of authorship operates as a guarantor of consistency and authenticity. -

In This Issue SFRA Review Business Craig Jacobsen English Department the State of the Review 2 Mesa Community College SFRA Business 1833 West Southern Ave

288 Spring 2009 SFRA Editors A publication of the Science Fiction Research Association Karen Hellekson Review 16 Rolling Rdg. Jay, ME 04239 [email protected] [email protected] In This Issue SFRA Review Business Craig Jacobsen English Department The State of the Review 2 Mesa Community College SFRA Business 1833 West Southern Ave. The State of the Organization 2 Mesa, AZ 85202 The State of the 2009 Conference 2 [email protected] The State of Scholarship and Service 3 [email protected] The State of the Web Site 3 The State of the 2008 Proceedings 4 Managing Editor Meeting Minutes 4 Janice M. Bogstad Feature: One Course McIntyre Library-CD Teaching the Zombie Renaissance 6 University of Wisconsin-Eau Claire Nonfiction Reviews 105 Garfield Ave. Digital Culture, Play, and Identity 8 Eau Claire, WI 54702-5010 American Exorcist 9 [email protected] Investigating Firefly and Serenity 9 Fiction Reviews Nonfiction Editor The Man with the Strange Head 10 Ed McKnight Mind over Ship 11 113 Cannon Lane The January Dancer 12 Taylors, SC 29687 The Graveyard Book 13 [email protected] Five Novels by Jamil Nasir: An Introduction 15 Media Reviews Fiction Editor Dr. Horrible’s Sing-Along Blog 17 Edward Carmien Dollhouse 18 29 Sterling Rd. Watchmen 19 Princeton, NJ 08540 Finding the Big Other and Making Him Pay 20 [email protected] Twilight 22 Bender’s Big Score and The Beast with a Billion Backs 23 Media Editor Futurama: Bender’s Game 24 Ritch Calvin Avatar: The Last Airbender 25 16A Erland Rd. The Dresden Files: Welcome to the Jungle 26 Stony Brook, NY 11790-1114 News [email protected] Calls for Papers 27 The SFRA Review (ISSN 1068-395X) is published four times a year by the Science Fiction Research Association (SFRA), and dis- tributed to SFRA members. -

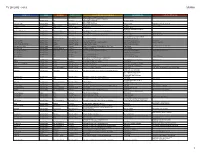

Tv Shows - 2019 Drama

TV SHOWS - 2019 DRAMA SHOW TITLE GENRE NETWORK SEASON STATUS STUDIO / PRODUCTION COMPANIES SHOWRUNNER(S) EXECUTIVE PRODUCERS 68 Whiskey Episodic Drama Paramount Network Ordered to Series CBS TV Studios / Imagine Television Roberto Benabib Fox TV Studios / 20th Century Fox Television, 911 Episodic Drama Fox Renewed Ryan Murphy Productions Timothy P. Minear, 20th Century Fox TV / 9-1-1: Lone Star Episodic Drama Fox Ordered to Series Ryan Murphy Productions Ryan P. Murphy Brad Falchuk; Timothy P. Minear A Million Little Things Episodic Drama ABC Television Renewed ABC Studios / Kapital Entertainment DJ Nash James Griffiths A Teacher Drama FX Network Ordered To Series FX Productions Hannah M. Fidell Jed Whedon; Maurissa Tancharoen; Agents of S.H.I.E.L.D. Episodic Drama ABC Television Renewed ABC Studios / Marvel Entertainment; Mutant Enemy Jeffrey Bell Alive Episodic Drama CBS Entertainment Not Picked Up CBS TV Studios Jason Tracey Robert Doherty All American Episodic Drama CW Network Renewed Warner Bros Television / Berlanti Productions Nkechi Carroll, Gregory G. Berlanti Greg Spottiswood; Leonard Goldstein; All Rise Episodic Drama CBS Entertainment Ordered to Series Warner Bros Television Michael Robin; Gil Garcetti Almost Paradise Episodic Drama WGN America Ordered to Series Electric Entertainment Gary Rosen; Dean Devlin Marc Roskin Amazing Stories Episodic Drama Apple Ordered To Series Universal Television LLC / Amblin Television Adam Horowitz; Edward Kitsis David H. Goodman Amazon/Russo Bros Project Episodic Drama Amazon Ordered To Series Amazon Studios / AGBO Anthony Russo; Joe Russo American Crime Story Episodic Drama FX Network Renewed Fox 21; FX Productions / B2 Entertainment; Color Force Ryan Murphy Brad Falchuk; D V.