Strauss Horn Concerto No

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Digital Concert Hall

Digital Concert Hall Streaming Partner of the Digital Concert Hall 21/22 season Where we play just for you Welcome to the Digital Concert Hall The Berliner Philharmoniker and chief The coming season also promises reward- conductor Kirill Petrenko welcome you to ing discoveries, including music by unjustly the 2021/22 season! Full of anticipation at forgotten composers from the first third the prospect of intensive musical encoun- of the 20th century. Rued Langgaard and ters with esteemed guests and fascinat- Leone Sinigaglia belong to the “Lost ing discoveries – but especially with you. Generation” that forms a connecting link Austro-German music from the Classi- between late Romanticism and the music cal period to late Romanticism is one facet that followed the Second World War. of Kirill Petrenko’s artistic collaboration In addition to rediscoveries, the with the orchestra. He continues this pro- season offers encounters with the latest grammatic course with works by Mozart, contemporary music. World premieres by Beethoven, Schubert, Mendelssohn, Olga Neuwirth and Erkki-Sven Tüür reflect Brahms and Strauss. Long-time compan- our diverse musical environment. Artist ions like Herbert Blomstedt, Sir John Eliot in Residence Patricia Kopatchinskaja is Gardiner, Janine Jansen and Sir András also one of the most exciting artists of our Schiff also devote themselves to this core time. The violinist has the ability to capti- repertoire. Semyon Bychkov, Zubin Mehta vate her audiences, even in challenging and Gustavo Dudamel will each conduct works, with enthusiastic playing, technical a Mahler symphony, and Philippe Jordan brilliance and insatiable curiosity. returns to the Berliner Philharmoniker Numerous debuts will arouse your after a long absence. -

Communications and External Relations Intern Will Play an Important Role in the Communications and External Relations Department of the Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra

The Communications and External Relations Intern will play an important role in the Communications and External Relations Department of the Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra. This flexible unpaid internship will allow the student to engage in many aspects of marketing and public relations for the symphony, including, but not limited to, graphic design, press release writing, copywriting, social media engagement, media list updates and creation, and event promotion, among other duties. Interns will have the opportunity to generate writing and design samples for a portfolio from assignments for newsletters, email blasts, social media posts, etc. We are specifically interested in interns who can contribute to a variety of communication areas with an emphasis on writing and design. Organization Description: The Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra, known for its artistic excellence for more than 120 years, is credited with a rich history of the world’s finest conductors and musicians, and a strong commitment to the Pittsburgh region and its citizens. Past music directors have included Fritz Reiner (1938-1948), William Steinberg (1952-1976), Andre Previn (1976-1984), Lorin Maazel (1984-1996) and Mariss Jansons (1995-2004). This tradition of outstanding international music directors was furthered in fall 2008, when Austrian conductor Manfred Honeck became music director of the Pittsburgh Symphony. The orchestra has been at the forefront of championing new American works, and gave the first performance of Leonard Bernstein’s Symphony No. 1 “Jeremiah” in 1944. The Pittsburgh Symphony has a long and illustrious history in the areas of recordings and radio concerts. As early as 1936, the Pittsburgh Symphony broadcast on the airwaves coast-to-coast and in the late 1970s it made the ground breaking PBS series “Previn and the Pittsburgh.” The orchestra has received increased national attention since 1982 through network radio broadcasts on Public Radio International, produced by Classical WQED-FM 89.3, made possible by the musicians of the Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra. -

CHICAGO SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA RADIO BROADCASTS Broadcast Schedule – Fall 2019

CHICAGO SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA RADIO BROADCASTS Broadcast Schedule – Fall 2019 PROGRAM #: CSO 19-42 RELEASE DATE: October 11, 2019 Michael Tilson Thomas and Gautier Capuçon Stravinsky: Scènes de ballet Saint-Saens: Cello Concerto No. 1 in A Minor, Op. 33 (Gautier Capuçon, cello) Prokofiev: Suite from Romeo and Juliet Strauss: Death and Transfiguration, Op. 24 (Donald Runnicles, conductor) PROGRAM #: CSO 19-43 RELEASE DATE: October 18, 2019 Marin Alsop and Hilary Hahn Brahms: Academic Festival Overture, Op. 80 Sibelius: Violin Concerto in D Minor, Op. 47 (Hilary Hahn, violin) Rachmaninov: Symphony No. 2 in E Minor, Op. 27 PROGRAM #: CSO 19-44 RELEASE DATE: October 25, 2019 Riccardo Muti conducts Sheherazade Mozart: Overture to Don Giovanni, K. 527 Mozart: Symphony No. 40 in G Minor, K. 550 Rimsky-Korsakov: Sheherazade (Robert Chen, violin) Beethoven: Symphony No. 1 in C Major, Op. 21 (Fritz Reiner, conductor) PROGRAM #: CSO 19-45 RELEASE DATE: November 1, 2019 Riccardo Muti and Joyce DiDonato Bizet: Roma Symphony in C Berlioz: The Death of Cleopatra (Joyce DiDonato, mezzo-soprano) Respighi: Pines of Rome Prokofiev: Romeo and Juliet, Op. 64: Montagues and Capulets Juliet the Young Girl Minuet Romeo and Juliet Romeo at Juliet’s Tomb PROGRAM #: CSO 19-46 RELEASE DATE: November 8, 2019 Riccardo Muti conducts Rossini's Stabat mater Mozart: Kyrie in D Minor, K. 341 (Chicago Symphony Chorus; Duain Wolfe, director) Cherubini: Chant sur la mort de Joseph Haydn (Krassimira Stoyanova, soprano; Dmitry Korchak, tenor; Enea Scala, tenor; Chicago Symphony -

MAHLER LORIN MAAZEL P2013 Philharmonia Orchestra C2013 Signum Records SYMPHONY NO

CTP Template: CD_DPS1 COLOURS Compact Disc Booklet: Double Page Spread CYAN MAGENTA Customer YELLOW Catalogue No. BLACK Job Title Page Nos. Recorded at Southbank Centre’s Royal Festival Hall, London, 17 April 2011 Producer – Misha Donat Engineer – Jonathan Stokes, Classic Sound Ltd Design – With Relish (for the Philharmonia Orchestra) and Darren Rumney Cover image CLebrecht Music & Arts MAHLER LORIN MAAZEL P2013 Philharmonia Orchestra C2013 Signum Records SYMPHONY NO. 2, RESURRECTION 24 1 291.0mm x 169.5mm CTP Template: CD_DPS1 COLOURS Compact Disc Booklet: Double Page Spread CYAN MAGENTA Customer YELLOW Catalogue No. BLACK Job Title Page Nos. “On Mahler” Mahler’s earlier symphonies frequently draw GUSTAV MAHLER on the world of his Wunderhorn songs – A century after his death, Mahler’s music settings of simple folk poems about birds and SYMPHONY NO. 2, RESURRECTION resonates more powerfully than ever. Its animals, saints and sinners, soldiers and their unique mix of passionate intensity and lovers. But this apparently naive, even childlike CD1 terrifying self-doubt seems to speak directly to tone is found alongside vast musical our age. One moment visionary, the next 1 I. Allegro maestoso 25.13 canvasses that depict the end of the world. In despairing, this is music that sweeps us up in quieter, more intimate movements, Mahler CD2 its powerful current and draws us along in its seems to speak intimately and directly to the 1 II. Andante moderato. Sehr gemächlich 11.25 drama. We feel its moments of ecstatic rapture listener, but the big outer movements are 2 III. Scherzo. In ruhig fliessender Bewegung 12.14 and catastrophic loss as if they were our own. -

[email protected] MANFRED HONECK to Conduct

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE March 28, 2018 Contact: Katherine E. Johnson (212) 875-5700; [email protected] MANFRED HONECK To Conduct SIBELIUS’s Violin Concerto with NIKOLAJ ZNAIDER as Soloist Mr. Honeck’s Arrangement of DVOŘÁK’s Rusalka Fantasy Selections from TCHAIKOVSKY’s Sleeping Beauty May 3–5 and 8, 2018 NIKOLAJ ZNAIDER To Make New York Philharmonic Conducting Debut TCHAIKOVSKY’s Symphony No. 1, Winter Dreams ELGAR’s Cello Concerto with JIAN WANG in Philharmonic Subscription Debut May 10–12, 2018 Manfred Honeck will return to the New York Philharmonic to conduct Sibelius’s Violin Concerto, with Nikolaj Znaider as soloist; Mr. Honeck’s own arrangement of Dvořák’s Rusalka Fantasy, orchestrated by Tomáš Ille; and selections from Tchaikovsky’s Sleeping Beauty, Thursday, May 3, 2018, at 7:30 p.m.; Friday, May 4 at 11:00 a.m.; Saturday, May 5 at 8:00 p.m.; and Tuesday, May 8 at 7:30 p.m. The following week, Nikolaj Znaider will make his New York Philharmonic conducting debut leading Elgar’s Cello Concerto, with Jian Wang in his subscription debut, and Tchaikovsky’s Symphony No. 1, Winter Dreams, Thursday, May 10, 2018, at 7:30 p.m.; Friday, May 11 at 8:00 p.m.; and Saturday, May 12 at 8:00 p.m. Manfred Honeck and Nikolaj Znaider previously collaborated on Sibelius’s Violin Concerto with the Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra (PSO), in Pittsburgh and on tour in 2012. Mr. Znaider also conducted the PSO that year in music by Elgar, Wagner, and Mozart. Manfred Honeck completed his arrangement of Dvořák’s Rusalka Fantasy in 2015 and led its first performances with the Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra shortly after. -

Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra 2017-2018 Radio Broadcast Season

Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra 2017-2018 Radio Broadcast Season Program 1 Rhapsody in Blue Gala Manfred Honeck, conductor; Lang Lang, piano Program 2 STAFFORD SMITH: Star Spangled Banner GLINKA: Overture to Ruslan and Ludmila MORRICONE: “Gabriel’s Oboe” from “The Mission” TCHAIKOVSKY: Violin Concerto DVORAK: Symphony No. 9, “From the New World” MACMILLAN: Fanfare for Pittsburgh Manfred Honeck, conductor; Cynthia Koledo DeAlmeida, oboe; Noah Bendix-Balgley, violin Program 3 ADAMS: Lollapalooza (PSO premiere) BRAHMS: Violin Concerto PIGOVAT: Manfred Honeck 10th Anniversary Commission SAINT-SAENS: Symphony No. 3, “Organ” Manfred Honeck, conductor; Christian Tetzlaff, violin Program 4 MUSSORGSKY: Scherzo CHOPIN: Piano Concerto No. 2 RACHMANINOFF: Symphony No. 2 Christoph Konig, conductor; Yulianna Avdeeva, piano Program 5 BEETHOVEN: Symphony No. 6 MAHLER: Twelve Songs from Des Knaben Wunderhorn Manfred Honeck, conductor; Matthias Goerne, baritone Program 6 STRAVINSKY: Petrushka OFFENBACH: Selections from La gaite parisienne RAVEL: Bolero Yan Pascal Tortelier, conductor Program 7 BEETHOVEN: Overture to Egmont BRUCH: Violin Concerto No. 1 SHOSTAKOVICH: Symphony No. 5 Kryzysztof Urbanski, conductor; Ray Chen, violin Program 8 MACMILLAN: Manfred Honeck 10th Anniversary Commission SCHUMANN: Cello Concerto BEETHOVEN: Symphony No. 3, “Eroica” Manfred Honeck, conductor; Alisa Weilerstein, cello Program 9 BARTOK: Music for Strings, Percussion and Celesta SCHUBERT: Symphony No. 9, “The Great” Christoph von Dohnanyi, conductor Program 10 MUSSORGSKY: -

October 20, 2005

for immediate release September 1, 2009 MUSIC DIRECTOR MANFRED HONECK LEADS THE PITTSBURGH SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA ON A EUROPEAN FESTIVALS TOUR HONECK AND PSO TO CLOSE PRESTIGIOUS LUCERNE FESTIVAL Pittsburgh Regional Alliance Joins PSO to Preview Region’ s Assets Preceding Pittsburgh (G-20) Summit SEPTEMBER 15 – 20, 2009 PITTSBURGH – Music Director Manfred Honeck leads the Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra (PSO), in their European debut together, in two previously-announced performances to close the renowned Lucerne Festival in Lucerne, Switzerland in September 2009. The Orchestra also performs two concerts in Germany – one at the Philharmonie Essen and another at the Beethoven Festival in Bonn. Featured soloists at the festivals are violinist Viktoria Mullova and soprano Christine Schäfer, and repertoire includes Weber’ s Overture to Der Freischü tz, Beethoven’ s Violin Concerto, Dvořá k’ s Eighth Symphony, Strauss’ Four Last Songs, and Bruckner’ s Fourth Symphony. Join the PSO on tour, through photos and blogs, at www.pittsburghsymphony.org. - more - Heinz Hall, 600 Penn Avenue, Pittsburgh, PA 15222 | 412.392.4900 | www.pittsburghsymphony.org Lawrence Tamburri, president & CEO | Richard P. Simmons, board chairman | Manfred Honeck, music director Leonard Slatkin, principal guest conductor | Marek Janowski, Otto Klemperer guest conductor chair | Marvin Hamlisch, principal pops conductor Following the success of two prior years of partnership, the Pittsburgh Regional Alliance (PRA) joins the PSO on its European Festivals tour to promote investment opportunities in the Pittsburgh region. In Germany and Switzerland with the PSO, the PRA once again leverages the orchestra as a world-class cultural asset to introduce the value of doing business in Pittsburgh to global leaders. -

Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra Manfred Honeck, Conductor Till Fellner, Piano

Sunday, May 19, 2019 at 3:00 pm Symphonic Masters Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra Manfred Honeck, Conductor Till Fellner, Piano BEETHOVEN Piano Concerto No. 5 in E-flat major (“Emperor”) The Program (1809) Allegro Adagio un poco mosso Rondo: Allegro Mr. Fellner will perform Beethoven’s cadenza. Intermission MAHLER Symphony No. 5 in C-sharp minor (1901–02) Trauermarsch. In gemessenem Schritt. Streng. Wie ein Kondukt Stürmisch bewegt. Mit größter Vehemenz Scherzo. Kräftig, nicht zu schnell Adagietto. Sehr langsam Rondo-Finale. Allegro Please make certain all your electronic devices are switched off. These programs are supported by the Leon Levy Fund for Symphonic Masters. Symphonic Masters is made possible in part by endowment support from UBS. This performance is made possible in part by the Josie Robertson Fund for Lincoln Center. The Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra tour performance is sponsored by BNY Mellon. Steinway Piano David Geffen Hall Great Performers Support is provided by Rita E. and Gustave M. Hauser, The Shubert Foundation, The Katzenberger Foundation, Inc., Audrey Love Charitable Foundation, Great Performers Circle, Lincoln Center Spotlight, Chairman’s Council, and Friends of Lincoln Center Public support is made possible by the New York State Council on the Arts with the support of Governor Andrew M. Cuomo and the New York State Legislature Endowment support for Symphonic Masters is provided by the Leon Levy Fund Endowment support is also provided by UBS Nespresso is the Official Coffee of Lincoln Center NewYork-Presbyterian is the Official Hospital of Lincoln Center Visit LCGreatPerformers.org for information on the 2019/20 season of Great Performers. -

[email protected] ITZHAK PERLMAN to CONDUCT A

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE May 11, 2016 Contact: Katherine E. Johnson (212) 875-5718; [email protected] ITZHAK PERLMAN TO CONDUCT AND PERFORM WITH THE NEW YORK PHILHARMONIC BEETHOVEN’s Romances Nos. 1 and 2 for Violin and Orchestra BRAHMS’s Symphony No. 4 BRAHMS’s Academic Festival Overture November 15, 2016 Itzhak Perlman will return to the New York Philharmonic to conduct and perform Beethoven’s Romances Nos. 1 and 2 for Violin and Orchestra, and to conduct Brahms’s Symphony No. 4 and Academic Festival Overture, Tuesday, November 15, 2016, at 7:30 p.m. This concert will mark Itzhak Perlman’s 84th appearance with the New York Philharmonic. He has conducted and performed with the Orchestra twice before: in October 2005 and March 2004. Of the most recent dual appearance, The New York Times wrote: “Just by being Itzhak Perlman, this particular conductor had the Philharmonic’s string players emulating his own relaxed warmth and breadth of tone.” “It’s a pleasure for me to return to the podium of the New York Philharmonic to conduct this great orchestra in their 175th anniversary season and perform two of my favorite composers, Beethoven and Brahms,” said Itzhak Perlman. Itzhak Perlman made his New York Philharmonic debut in May 1965 as the 1964 Leventritt Award Winner in a program conducted by William Steinberg. Most recently, he performed in the 2012–13 season Opening Gala Concert, led by Music Director Alan Gilbert. Artists Undeniably the reigning virtuoso of the violin, Itzhak Perlman enjoys superstar status rarely afforded a classical musician. Beloved for his charm and humanity as well as his talent, he is treasured by audiences throughout the world who respond not only to his remarkable artistry, but also to his irrepressible joy for making music. -

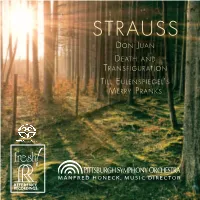

Strauss Don Juan

STRAUSS DON JUAN DEATH AND TRANSFIGURATION TILL EULENSPIEGEL’S MERRY PRANKS fresh! MANFRED HONECK, MUSIC DIRECTOR Richard Strauss from a photograph by Fr. Müller, Munich here are few composers who have such an impressive ability to depict a story together with single existential moments in instrumental music as Richard Strauss in his Tondichtungen (“tone poems”). Despite the clear structure that the music follows, a closer interpretative look reveals many unanswered questions. FTor me, it was the in-depth discovery and exploration of these details that appealed to me, as the answers resulted in surprising nuances that helped to shape the overall sound of the pieces. One such example is the opening of Tod und Verklärung (Death and Transfiguration) where it is obvious that the person on the deathbed breathes heavily, characterized by the second violins and violas in a syncopated rhythm. What does the following brief interjection of the flutes mean? The answer came to me while thinking about my own dark, shimmering farmhouse parlor where I lived as a child. There, we had only a sofa and a clock on the wall that interrupted the silence. The flutes remind me of the ticking clock hand. This is why it has to sound sober, unemotional, mechanistic and almost metallic. Another such example is the end of Don Juan where the strings seem to tremble. It is here that one can hear the last convulsions of the hero’s dying body. This must sound nervous, dreadful and dramatic. For this reason, I took the liberty to alter the usual sound. I ask the strings to gradually transform the tone into an uncomfortable, convulsing, and shuddering ponticello until the final pizzicato marks the hero’s last heartbeat. -

Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra International Tours

Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra International Tours 1947 Tour of Mexico Fritz Reiner, conductor 1964 (August 10-November 1) Tour of Europe and Near East William Steinberg, conductor. State Department funded three-month tour of Europe, and what was then referred to as Near East. Cities: Rome, Athens, Beirut, Baalbeck, Tehran, Lucerne, Edinburgh, Luxembourg, Frankfurt, Berlin, Warsaw, Krakow, Katowice, Lodz, Belgrade, Sarajevo, Ljubljana, Zagreb, Munich, Milan, Turin, Florence, Bilbao, Madrid, Barcelona, Lisbon, Oporto and Reykjavik. 1973 Tour of Japan, Alaska and Oregon William Steinberg and Donald Johanos, conductors 1978 (May 21-June 10) European Tour André Previn, conductor. Cities: Austria (Vienna, Linz, Innsbruck), Germany (Munich, Stuttgart, Bonn, Frankfurt, Berlin, Hanover), Norway (Bergen), Sweden (Goteborg, Stockholm) and England (London). 1980 (Aug 25-31) Mexico City Eduardo Mata and Rafael Frühbeck de Burgos, conductors. Four concerts in Mexico City. 1982 (May 23-June 13) European Tour André Previn, conductor. Cities: Bonn, Linz, Vienna, Zurich, Munich, Stuttgart, Frankfurt, Dusseldorf, Paris, Brussels, Berlin and London. 1984 Hong Kong Festival André Previn, conductor 1984 Casals Festival in Puerto Rico Herbert Blomstedt, conductor 1985 (August 14-September 8) European Tour Lorin Maazel, conductor. Included Salzburg and Edinburgh festivals. Cities: Dublin, Cork, Edinburgh, London, Bristol, Zurich, Lucerne, Montreux, Salzburg, Bonn, Düsseldorf, Berlin, Brussels, Antwerp and Paris. 1987 (April 14-May 4) Far East Tour Japan and Hong Kong Lorin Maazel, conductor. Historic visit to Beijing, China. First U.S. orchestra to visit in the ’80s and only the third ever to do so. Cities: Tokyo, Yokohama, Osaka, Nagoya, Matsudo, Hong Kong and Beijing. 1987 Edinburgh Festival Lorin Maazel and Michael Tilson Thomas, conductors. -

No Arrogance

Profil By Manuel Brug No Arrogance Manfred Honeck, the conductor from Vorarlberg, Austria, has worked his way into the premier league of his field. He is giving guest performances in his old home with the Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra. Where are Pittsburgh’s secrets? This beautiful city, green and picturesquely situated, as if a peninsula, on the Monongahela and Allegheny Rivers, has a functioning Downtown that is not deserted at night. There is even a market square with street cafés in the shadow of the postmodern glass and steel cathedral built by Philip Johnson. The time of heavy industry in the city with America’s biggest inland harbour, but a population of just 300,000, is long gone. These days Pittsburgh banks on universities, clinics and services as well as clean business, which also includes culture. It does not do this just with its rich museums, but also with the Cultural District in the heart of the revived city. Its flagship is the 121-year-old Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra (PSO). It resides in the Heinz Hall, a marble-clad venue donated by the ketchup dynasty in 1970. Here at last we understand why the theatre seats have to be velvety red: 2600 examples of corporate identity. This vibrantly festive setting is home to one of the best orchestras in the country, but one that has strangely never found its way into the ominous ‘Top Five’. Was the provincial location to blame? And yet it has attracted luminaries such as Otto Klemperer, Fritz Reiner, William Steinberg and André Previn as principal conductors: strict orchestral educators who trained their ensemble with a cast- iron hand to perform with precision.